Alan Campbell

Alan Campbell, the son of Harry L. Campbell and Hortense Eichel Campbell, was born in Richmond, Virginia, on 21st February, 1904. His father was of Scottish descent and worked as a tobacco leaf salesman. His mother's family, the Eichels, were Jewish emigres from Alsace.

Campbell graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and moved to New York City where he worked as an actor and got small parts with the repertory company established by Eva Le Gallienne. Over the next few years he appeared in a dozen Broadway shows, including the hit musical Show Boat and the play Design for Living. Campbell also worked as a journalist and had some articles published in The New Yorker.

In 1931 Campbell was given a three-month writing contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He later recalled: "After some weeks, I ran away. I could not stand it anymore. I just sat in a cell-like office and did nothing. The life was expensive and the thousands of people I met were impossible. They never seemed to behave naturally, as if all their money gave them a wonderful background they could never stop to marvel over. I would imagine the Klondike like that - a place where people rush for gold." However, Campbell was convinced that with the right partner he could make it as a script-writer.

In 1932 Robert Benchley introduced Campbell to Dorothy Parker, an extremely talented writer. Parker's first collection of poems, Enough Rope (1926), received some great reviews. She also published two collections of short stories: Laments for the Living (1930) and After Such Pleasure (1931). Franklin Pierce Adams wrote in the New York Herald-Tribune: "More certain than either death or taxes is the high and shining art of Dorothy Parker... Bitterness, humour, wit, yearning for beauty and love, and a foreknowledge of their futility - with rue her heart is laden, but her lads are gold-plated - these, you might say, are the elements of the Parkerian formula; these, and the divine talent to find the right word and reject the wrong one. The result is a simplicity that almost startles."

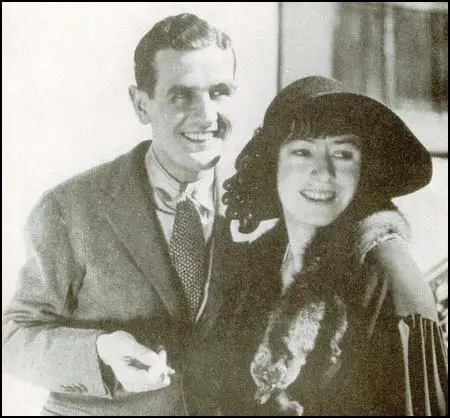

According to Marion Meade, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989): "She (Parker) was immediately impressed by Alan's golden good looks, the fine bone structure, the fair hair and dazzling smile that made it seem as if he had just stepped indoors on a June day. He resembled Scott Fitzgerald when Scott had been young and healthy, before he began drinking heavily, and some people thought him far better looking. Alan, like Scott, had a face that was a touch too pretty for a man, the kind of features that caused people to remark he would have made a splendid woman. He was typecast by producers as a classic juvenile."

Campbell later recalled: "Dottie was the only woman I ever knew whose mind was completely attuned to mine... No one in the world had made me laugh as much as Dottie." John Keats has pointed out: "They had arrived in each other's lives at the very moment each most needed the other. Alan was at a turning point. He was an unsung actor of minor roles in unimportant plays... he had faced up to the fact that his talents as an actor were meagre and that there was no real point in his continuing in a career in which he would never do particularly well."

Campbell was twenty-eight years old and Parker was thirty-nine. However, they had much to offer each other. Campbell needed a writing-partner and Parker needed someone to look after her. They rented an apartment together in New York City. According to one source: "Alan had bought the food, done the cooking, done all the interior decorating in their apartment, painted all the insides of the bureau drawers, cleaned up after the dogs, washed and dried the dishes, made the beds, told Dorothy to wear her coat on cold days, shaken the cocktails, paid the bills, amused her, adored her, made love to her, got her to cut down on her drinking, otherwise created space and time in her life for her to write."

Another friend, Donald Ogden Stewart, argued: "He (Alan Campbell) took her (Dorothy Parker) and probably kept her living. He was important in so far as taking care of her was concerned, and she was well worth taking care of. Alan was an actor, and he may have been playing a part which little by little took over, but he wasn't a villain. He kept her living and working." Ruth Goodman Goetz added: "Alan bought her clothes, fussed with her hairstyle and her perfume... Dottie was delighted to have this handsome creature around."

Campbell and Parker married in 1934 in Raton, New Mexico, and moved to Hollywood. They signed ten-week contracts with Paramount Pictures, with Campbell earning $250 per week and Parker earning $1,000 per week. This would later be increased to over $2,000 a week. Their first movie scripts included Here Is My Heart (1934) Hands Across the Table (1935), The Moon's Our Home (1936), Suzy (1936), Three Married Men (1936) and Lady Be Careful (1936).

Parker later recalled: "Through the sweat and the tears I shed over my first script, I saw a great truth - one of those eternal, universal truths that serve to make you feel much worse than you did when you started. And that is that no writer, whether he writes from love or from money, can condescend to what he writes. What makes it harder in screenwriting is the money he gets. You see, it brings out the uncomfortable little thing called conscience. You aren't writing for the love of it or the art of it or whatever; you are doing a chore assigned to you by your employer and whether or not he might fire you if you did it slackly makes no matter. You've got yourself to face, and you have to live with yourself."

Campbell liked working in Hollywood. John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has pointed out: "Campbell... was good at the work he was asked to do. His talents as a writer were perfectly matched to Hollywood's standards. His work was a labour of love. He loved being in Hollywood. He was thrilled to meet stars. He was a creature of the theatre and the films, and all the people who had to do with the stage and screen were at one time or another in Hollywood: he was at the centre of his world... It was not just the money, it was also the glamour and the success that he loved."

Parker and Campbell lived in a Beverly Hills mansion with a butler and a cook. They also purchased a large Colonial house in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It was called Fox House Farm. As a result of the Great Depression prices were low and they purchased it for $4,500, less than what the couple was being paid for a week's pay in Hollywood. Dorothy became pregnant, but now aged 42, she miscarried after three months.

Hiram Beer worked as a gardener, chauffeur and carpenter at the Fox House Farm was amazed at the vast amount of alcohol the couple consumed. He said Parker drank Manhattans and Campbell, Scotch on the rocks, and when not this, they shared pitchers of Martinis: "They'd bring it in by the cases, and both of them used to run around with drinks in their hands even when there was no company there. When they had people there, they had people who felt they had to drink just because they were there, and that's what there was to do. They'd all get up past noon, and after their lunch, or breakfast as it might have been, they'd start drinking until late at night."

John Keats, has suggested that "Dorothy Parker... lived with a fretful husband in a rather oddly furnished house, quarrelling with her friends, allowing herself to grow dumpy in barren middle age, wasting her time on silly scripts, stunning herself with alcohol and sleeping pills, loving the working man in general while despising him in particular, ridiculing as meretricious the artistry that had enabled her to become the mistress of a New York apartment, a California mansion, and a country estate. Between 1935 and 1937, she spent herself as she spent her money: as if she hated both."

In 1936 Parker, Campbell and Donald Ogden Stewart met a former Berlin journalist, Otto Katz. He told them about what was happening in Nazi Germany. Stewart recalled that when Katz began to describe the rule of Adolf Hitler "the details of which he had been able to collect only through repeatedly risking his own life, I was proud to be sitting beside him, proud to be on his side in the fight." Stewart and Parker decided to join with a group of people involved in the film industry who were concerned about the growth of fascism in Europe to establish the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL). Members included Alan Campbell, Walter Wanger, Dashiell Hammett, Cedric Belfrage, John Howard Lawson, Clifford Odets, Dudley Nichols, Frederic March, Lewis Milestone, Oscar Hammerstein II, Ernst Lubitsch, Mervyn LeRoy, Gloria Stuart, Sylvia Sidney, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chico Marx, Benny Goodman, Fred MacMurray and Eddie Cantor. Another member, Philip Dunne, later admitted "I joined the Anti-Nazi League because I wanted to help fight the most vicious subversion of human dignity in modern history".

Campbell and Dorothy Parker held left-wing political views and with Donald Ogden Stewart they formed the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. He was also a strong supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain and during then Spanish Civil War was a member of the Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee and the Motion Picture Artists Committee to Aid Republican Spain. In October 1937 Parker visited Spain and made a broadcast from Madrid Radio.

Alan Campbell became increasingly concerned about Parker's political activity. As John Keats pointed out: "He (Campbell grew more and more concerned. He told Dorothy that her politics were dangerous. Being against Hitler might be all very well, but the kind of people who were most strongly against Hitler were also on the side of the labour unions, and the studios didn't like people who were on the side of unions. Making speeches in Hollywood couldn't hurt Hitler, Alan argued, but it could very well hurt Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell with the studios."

In 1937 Parker and Campbell were recruited to write the screenplay for A Star is Born (1937). The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning the award for Best Story. Other films they worked on included Trade Winds (1938), The Cowboy and the Lady (1938), Sweethearts (1938), Trade Winds (1938), The Little Foxes (1941), Weekend for Three (1941) and Saboteur (1942). Some people claimed that Campbell only got work because of Parker. Budd Schulberg disagreed: "Her (Parker) work habits were terrible, but Alan was extremely disciplined. He dragged her along. At United Artists, I watched how they worked... In his own right he was a really good screenwriter, maybe because he'd once been an actor, but nobody gave him credit."

Left-wing writers such as Campbell and Parker were attacked by Martin Dies, the chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In 1940 Parker responded by arguing: "The people want democracy - real democracy, Mr. Dies, and they look toward Hollywood to give it to them because they don't get it any more in their newspapers. And that's why you're out here, Mr. Dies - that's why you want to destroy the Hollywood progressive organizations - because you've got to control this medium if you want to bring fascism to this country." It was pointed out that people like Campbell and Parker were guilty of being a "premature anti-Fascists".

During the Second World War Campbell volunteered to join the United States Army Air Forces. In 1942 he was sent to the Air Force ground school at Miami Beach where he served with Joshua Logan, the Broadway director. Parker visited Campbell as often as she could. Nedda Harrigan, Logan's future wife, commented that she was with them at a party on the base: "They were terribly intimate, only if wasn't cozy or jolly, more like a couple of vipers. Of course we were all drinking heavily, because that was standard procedure in the air force, but she was in a bad temper and later on they had a terrible fistfight." Harrigan urged Parker not to take the quarrel seriously as war was difficult and they were all in the "same boat". Parker disagreed, replying, "my boat is leaking".

In 1943 Parker applied to join the Women's Army Corps but was rejected as she had passed her fiftieth birthday. Parker hated being middle-aged and wanted to skip her fifties and get to the seventies and eighties. "People ought to be one of two things, young or old. No; what's the good of fooling? People ought to one of two things, young or dead." Parker also became depressed by the early deaths of close friends, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun and Robert Benchley.

Parker applied to become a foreign correspondent. She was once again rejected, this time because the government was unwilling to grant passports to people with well-known left-wing views. She therefore followed Campbell from camp to camp. In the summer of 1943 Campbell was based in Northampton, Hampshire County, and Parker stayed as a house-guest with one of his fellow officers, Robeson Bailey. His wife said: "She was self-effacing; she was quiet. I wanted to protect her. She was so damned decent, and yet she had this legend of indecency about her, encrusted with the New York glamour... They seemed to be just a very happily married couple despite the disparity in age. He obviously must have had a mother thing about her, I should think." In November, 1943, Campbell was sent to London where he served as an officer in Army Intelligence.

In July 1944 Dorothy Parker wrote an article for Vogue Magazine about what it was like to be the wife of a soldier serving overseas. This was based partly on her experiences of her first husband, Edwin Pond Parker in the First World War: "You say goodnight to your friends, and know that tomorrow you will meet them again, sound and safe as you will be. It is not like that where your husband is. There are the comrades, closer in friendship to him than you can ever be, whom he has seen comic or wild or thoughtful; and then broken or dead. There are some who have gone out with a wave of the hand and a gay obscenity, and have never come back. We do not know such things; prefer, and wisely, to close our minds against them... I have been trying to say that women have the easier part in war. But when the war is over - then we must take up. The truth is that women's work begins when war ends, begins on the day their men come home to them. For who is that man, who will come back to you? You know him as he was; you have only to close your eyes to see him sharp and clear. You can hear his voice whenever there is silence. But what will he be, this stranger who comes back? How are you to throw a bridge across the gap that has separated you - and that is not the little gap of months and miles? He has seen the world aflame; he comes back to your new red dress. He has known glory and horror and filth and dignity; he will listen to you tell of the success of the canteen dance, the upholsterer who disappointed, the arthritis of your aunt. What have you to offer this man? There have been people you never knew with whom he has had jokes you could not comprehend and talks that would be foreign to your ear. There are pictures hanging in his memory that he can never show to you. Of this great part of his life, you have no share... things forever out of your reach, far too many and too big for jealousy. That is where you start, and from there you go on to make a friend out of that stranger from across a world."

In 1947 Dorothy Parker became involved with Ross Evans, a young actor. Beatrice Ames Stewart said that he was "a beautiful hunk" who looked like Victor Mature. A woman at a party complimented him on his wonderful sun tan. Parker said he had the "hue of availability". Later that year she divorced Alan Campbell. When her friend, Vincent Sheean, said he felt sorry for Campbell she commented: "Oh, don't worry about Alan. He will always land on somebody's feet."

Parker wrote the screenplays for two more films, A Woman Destroyed (1947) and Lady Windermere's Fan (1949). She also wrote a play with Ross Evans entitled The Coast of Illyria that was based on the life of Charles Lamb. It opened in Dallas in the spring of 1949. It received reasonable reviews but it was not transferred to Broadway. It was performed in London and at the Edinburgh Festival but it was not a success. Its failure was one of the reasons why Evans left Parker. According to Parker another reason was that Evans discovered she was "half a Jew".

Parker now contacted Campbell who had found it difficult to find work since their divorce. He agreed to remarry her. Parker told her friends: "I've been given a second chance. I've been given a second chance - and who in life gets a second chance?" Another friend said: "He (Alan) was marrying her because he wanted to help take care of her. Alan was so wonderful for her, and she would crucify him, but she relied on him and he was lovely to her." Their second marriage took place on 17th August, 1950.

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party. The list included Parker and Campbell. A free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. As a result both Alan Campbell and Parker were blacklisted.

John Keats has pointed out: "Alan Campbell was a victim of the Red hunt, despite his well-known objections to Dorothy Parker's pre-war political activities and his refusal to have anything to do with them. Because her career in films was over, he could not offer himself and Dorothy Parker as a writing team to any studio, nor was any studio willing to employ him alone, because he was the husband of a suspected Communist. To be unemployed in Hollywood is normally to be regarded as a pariah, but in these abnormal times it was something worse. No one knew who might be reported for his association with someone else, however slight that association might be; no one knew how suspect were the friends of his friends. There was no help for this: no one could say when, or whether, the terror would end... the House Committee on Un-American Activities said it had evidence that Dorothy Parker was a Communist. She was angrily noncommittal when questioned by newspaper reporters. She refused to become one of those who went crawling to the Committee, or to the studios, to wear the guise of a penitent and seek redemption and good fortune by being traitorous."

The couple left Hollywood and moved back to New York City. In April 1951, Parker and Campbell were visited by two FBI agents. They asked if they knew Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ella Winter and John Howard Lawson and if they had attended meetings of the American Communist Party with them. The agents reported: "She was a very nervous type of person... During the course of this interview, she denied ever having been affiliated with, having donated to, or being contacted by a representative of the Communist Party."

In Parker's FBI file was a letter sent by Walter Winchell to J. Edgar Hoover. It said that Winchell had been a close friend of Parker until "she became a mad fanatic of the Commy party line". Winchell asked Hoover if he knew that "Dorothy Parker, the poet and wit, who led many pro-Russian groups." As Marion Meade, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989) has pointed out: "Many friends of hers were blacklisted, denounced as traitors, subpoenaed, cited for contempt of Congress, and sentenced to prison terms... Practically all of Dorothy's friends on the board of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, whose national chairman she had been, went to jail after declining to turn over records to HUAC."

The journalist, Wyatt Emory Cooper met Parker and Campbell for the first time in 1956. "My memory is of a stark, bare, colourless, and impersonal room, with a large bone on the floor, dog toys on the gravy-coloured sofa, a dog, of course, and an agonized Alan facing a stricken-looking Dottie, who was then, as incredible as it seems to me now, actually fat. My impression was of a sad, bewildered young girl, angrily trapped inside an inappropriate and almost grotesque body. Of the desolate conversation, I remember only that she apologized repeatedly; for the disorder of the room, for her own appearance, for the behaviour of the dog, and for the absence of anything to drink... It was painful to witness the estrangement of two people who were forever to be deeply involved with each other. Loneliness and guilt were almost like physical presences in the space between them, and they spoke in short, stilted, and polite sentences with terrible silences in between, and, yet, there was a tenderness in the exchange, a grief for old hurts, and a shared reluctance to turn loose."

Alan Campbell died after taking an overdose of sleeping pills in Los Angeles on 14th June, 1963. The coroner's report showed that he had died of "acute barbiturate poisoning due to an ingestion of overdose" and listed him as a probable suicide. His friend, Nina Foch, said: "I don't think he meant to kill himself, but I also felt that he'd not unaccidently done the thing." According to John Keats: "A physician said it was not necessarily a case of suicide; it is not unusual for a drunken person, asleep under sedation by barbiturates, to strangle on his own vomit. It was decided that death had been caused by accident."

Primary Sources

(1) Marion Meade, Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989)

She (Parker) was immediately impressed by Alan's golden good looks, the fine bone structure, the fair hair and dazzling smile that made it seem as if he had just stepped indoors on a June day. He resembled Scott Fitzgerald when Scott had been young and healthy, before he began drinking heavily, and some people thought him far better looking. Alan, like Scott, had a face that was a touch too pretty for a man, the kind of features that caused people to remark he would have made a splendid woman. He was typecast by producers as a classic juvenile.

(2) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

They had arrived in each other's lives at the very moment each most needed the other. Alan was at a turning point. He was an unsung actor of minor roles in unimportant plays, and at the time of his marriage, he had faced up to the fact that his talents as an actor were meagre and that there was no real point in his continuing in a career in which he would never do particularly well. On the other hand, he had definite abilities as a script-writer, and he felt sure he could write successfully for the motion pictures.