Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin was born in London on 16th April, 1889. Both his parents were music hall entertainers and Charlie started appearing on the stage while still a child. His father, Charles Chaplin, deserted the family and eventually died of alcoholism. His mother, Hannah Chaplin, found it increasingly difficult to find work on the stage and in 1895 the family entered the Lambeth Workhouse.

Chaplin later wrote: "Although we were aware of the shame of going to the workhouse, when Mother told us about it both Sydney and I thought it adventurous and a change from living in one stuffy room. But on that doleful day I didn't realize what was happening until we actually entered the workhouse gate. Then the forlorn bewilderment of it struck me; for there we were made to separate, Mother going in one direction to the women's ward and we in another to the children's. How well I remember the poignant sadness of that first visiting day: the shock of seeing Mother enter the visiting-room garbed in workhouse clothes. How forlorn and embarrassed she looked! In one week she had aged and grown thin, but her face lit up when she saw us." Later, Charlie's mother had a mental breakdown and was sent to the Cane Hill Lunatic Asylum. He told a close friend: "I loved my mother almost more when she went out of her mind. She had been so poor and so hungry - I believe it was starving herself for us that affected her brain. She so wanted me to be a successful actor."

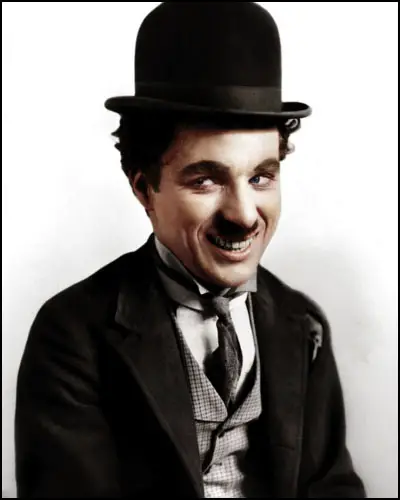

When he was sixteen Chaplin won the part of Billy in a West End production of Sherlock Holmes. He later joined Fred Karno's music hall revue. While touring the United States in 1913 Chaplin was discovered by the film producer Mack Sennett. Over the next couple of years Chaplin made a series of short slapstick films for Sennett's Keystone Company. In these films Chaplin developed a character that wore baggy pants, tight frock coat, large shoes on the wrong feet and a black derby hat.

By his thirteenth film, Caught in the Rain (1914), Chaplin began to direct his own films. Chaplin now slowed the pace of his films, reduced the number of visual jokes but increased the time spent on each one. Chaplin placed the emphasis on the character rather than slapstick events. The themes of his films became more serious and reflected his childhood experiences of poverty, hunger and loneliness. Chaplin's work revolutionized film comedy and turned it into an art form.

Chaplin's films were highly successful and became a household name throughout the world. When Chaplin first started with the Keystone Company he was paid $150 a week, by 1915 he was receiving $1,250. Three years later, when he joined First National, Chaplin signed cinema's first million-dollar contract. During this period Chaplin's films included The Tramp (1915), The Pawnshop (1915), Easy Street (1917), The Immigrant (1917) and A Dog's Life (1918).

In 1919 Chaplin joined with D.W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford to form United Artists, a company that enabled the stars to distribute their films without studio interference. It is also argued that it was in response to a rumour that the film companies intended to put a ceiling on the star salaries. Films produced by Chaplin and his company included The Kid (1921).

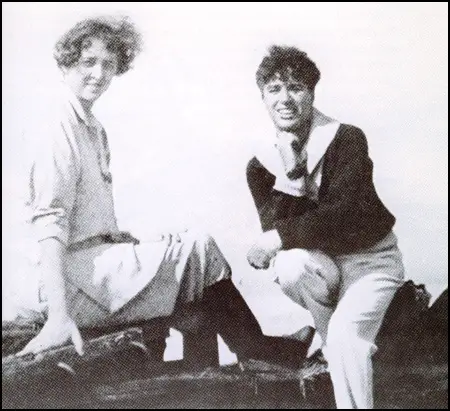

Chaplin agreed to be interviewed by Clare Sheridan, a reporter from New York World. She recorded in her diary: "It has been a wonderful evening - I seem to have been talking heart to heart with one who understands, who is full of deep thought and deep feeling. He is full of ideals and has a passion for all that is beautiful. A real artist... And then in spite of his emotional, enthusiastic temperament, with a soundness of judgement... You can see the sadness of the eyes - which the humour of his smile cannot dispel - this man has suffered... He is not Bolshevik nor Communist nor Revolutionary, as I heard rumoured. He is an individualist with the artist's intolerance of stupidity, insincerity, and narrow prejudice." Chaplin advised her against becoming too political: "Don't get lost on the path of propaganda. Live your life as an artist."

Sheridan began a romantic relationship with Chaplin. She later confessed that: "It was not exactly a love affair but a meeting of kindred spirits - we were like two fireflies intoxicated with the same magical feeling for beauty - dancing together by the waves, recognising each other's souls." They were constantly being followed by journalists. One newspaper published the headline: "Charlie Chaplin going to marry British Aristocrat". In one interview concerning age he answered truthfully: "Mrs. Sheridan is four years older than I am." When the article was published it claimed that Chaplin said: "She is old enough to be my mother." Eventually they decided to bring an end to the relationship.

Chaplin made a series of highly successful films including The Gold Rush (1925), The Circus (1928) and City Lights (1931). Chaplin became increasingly concerned with politics. A strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Chaplin's film, Modern Times (1936), was seen by some critics as an attack on capitalism. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), began compiling a file on Chaplin's activities, including his friendship with radicals such as Upton Sinclair, H. G. Wells, Hanns Eisner, Albert Einstein, Clare Sheridan and Harold Laski.

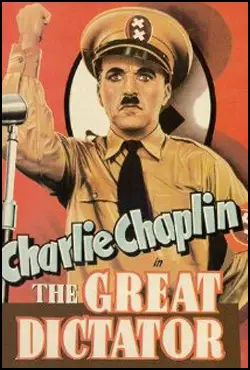

A strong opponent of racism, in 1937 Chaplin decided to make a film on the dangers of fascism. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography, attempts were made to stop the film being made: "Half-way through making The Great Dictator I began receiving alarming messages from United Artists. They had been advised by the Hays Office that I would run into censorship trouble. Also the English office was very concerned about an anti-Hitler picture and doubted whether it could be shown in Britain. But I was determined to go ahead, for Hitler must be laughed at." However, by the time The Great Dictator was finished, Britain was at war with Germany and it was used as propaganda against Adolf Hitler.

During the Second World War Chaplin played an active role in the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Others involved in this organization included Fiorello La Guardia, Vito Marcantonio, Wendell Willkie, Orson Welles, Rockwell Kent and Pearl Buck. Chaplin was also one of the major figures in the campaign during the summer of 1942 for the opening of a second-front in Europe.

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate people with left-wing views in the entertainment industry. In September 1947 Chaplin was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC but three times his meeting was postponed. Unknown to Chaplin, J. Edgar Hoover, and the FBI, now had a 1,900 page file on his political activities. Hoover advised the Attorney General that when Chaplin left the country he should be allowed to return.

In 1952 Chaplin visited London for the premiere of Limelight. When he arrived back he discovered his entry permit revoked and had been denied the right to live in the United States. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography: "My prodigious sin was, and still is, being a non-conformist. Although I am not a Communist I refused to fall in line by hating them."

Chaplin, blacklisted from making films in Hollywood, responded by making A King in New York (1957). The film stars Chaplin as the deposed king of Estrovia who flees to America where he is tormented by McCarthy style investigations. Chaplin was once again accused of being pro-communist and the film was not released in the United States.

While in exile, Chaplin wrote his memoirs, My Autobiography (1964) and directed the movie, A Countess from Hong Kong (1966). Despite the objections of J. Edgar Hoover, in 1972 Chaplin was invited back to the United States to receive a special award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He was also allowed to distribute his satire on McCarthyism, A King in New York.

Charles Chaplin died in Switzerland on 25th December, 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (1964)

Although we were aware of the shame of going to the workhouse, when Mother told us about it both Sydney and I thought it adventurous and a change from living in one stuffy room. But on that doleful day I didn't realize what was happening until we actually entered the workhouse gate. Then the forlorn bewilderment of it struck me; for there we were made to separate, Mother going in one direction to the women's ward and we in another to the children's.

How well I remember the poignant sadness of that first visiting day: the shock of seeing Mother enter the visiting-room garbed in workhouse clothes. How forlorn and embarrassed she looked! In one week she had aged and grown thin, but her face lit up when she saw us.

(2) in his autobiography, Charles Chaplin lists Upton Sinclair, H. G. Wells and Harold Laski. as important influences on his political views.

I now saw H. G. Wells frequently. After dinner friends arrived, among Professor Laski, who was still young-looking. Harold was a most brilliant orator. I heard him speak to the American Bar Association in California, and he talked unhesitatingly and brilliantly for an hour without a note. At H. G.'s flat that night, Harold told me of the amazing innovations in the philosophy of socialism.

Wells wanted to know how I became interested in socialism. It was not until I came to the United States and met Upton Sinclair, I told him. We were driving to his house in Pasadena for lunch and he asked me in his soft-spoken way if I believed in the profit system. It was a disarming question, but instinctively I felt it went to the very root of the matter, and from that moment I became interested and saw politics not as history but as an economic problem.

(3) During the 1932 presidential campaign, Charles Chaplin was a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The lugubrious Hoover sat and sulked, because his disastrous economic sophistry of allocating money at the top in the belief that it would percolate down to the common people had failed. And amidst all this tragedy he ranted in the election campaign that if Franklin Roosevelt got into office the very foundations of the American system - not an infallible system at that moment - would be imperiled.

However, Franklin D. Roosevelt did get into office, and the country was not imperiled. His Forgotten Man speech lifted American politics out of its cynical drowse and established the most inspiring era in American history. I heard the speech over the radio at Sam Goldwyn's beach-house. "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself" came over the air like a ray of sunlight. But I was sceptical, as were most of us. "Too good to be true," I said.

No sooner had Roosevelt taken office than he began to fit actions to his words, ordering a ten-day bank holiday to stop the banks from collapsing. That was a moment when America was at its best. Shops and stores of all kinds continued to do business on credit, even the cinemas sold tickets on credit, and for ten days, with Roosevelt and his so-called brains trust formulated the New Deal, the people acted magnificently.

Legislation was ordered for every kind of emergency: re-establishing farm credit to stop the wholesale robbery of foreclosures, financing big public projects, establishing the National Recovery Act, raising the minimum wage, spreading out jobs by shortening working hours, and encouraging the organization of labour unions. This was going to far; this was socialism, the opposition shouted. Whether it was or not, it saved capitalism from complete collapse. It also inaugurated some of the finest reforms in the history of the United States. It was inspiring to see how quickly the American citizen reacted to constructive government.

(4) In 1935 Charles Chaplin discussed the situation in Russia with H. G. Wells.

When H. G. Wells visited me in 1935 in California, I took him to task about his criticism of Russia. I had read his disparaging reports, so I wanted a first-hand account and was surprised to find him almost bitter about it.

"But is it not too early to judge?" I argued. "They have had a difficult task, opposition and conspiracy from within and from without. Surely in time good results should follow?"

At that time Wells was enthusiastic about what Roosevelt had accomplished with the New Deal, and was of the opinion that a quasi-socialism in America would come out of a dying capitalism. He seemed especially critical of Stalin, whom he had interviewed, and said that under his rule Russia had become a tyrannical dictatorship.

"If you, a socialist, believe that capitalism is doomed," I said, "what hope is there for the world if socialism fails in Russia?"

"Socialism won't fail in Russia, or anywhere else," he said, "but this particular development of it has grown into a dictatorship."

(5) In 1938 Charlie Chaplin decided to make a film about Adolf Hitler.

War was in the air again. The Nazis were on the march. How soon we forgot the First World War and its torturous four years of dying. How soon we forgot the appalling human debris: the basket cases - the armless, the legless, the sightless, the jawless, the twisted spastic cripples. Those that were not killed or wounded did not escape, for they were left with deformed minds. And now another war was brewing.

Alexander Korda in 1937 had suggested I should do a Hitler story based on mistaken identity, Hitler having the same moustache as the tramp: I could play both characters, he said. I did not think too much about the idea then, but now it was topical, and I was desperate to get working again. Then it suddenly struck me. Of course! As Hitler I could harangue the crowds in jargon and talk all I wanted to. And as the tramp I could remain more or less silent.

Half-way through making The Great Dictator I began receiving alarming messages from United Artists. They had been advised by the Hays Office that I would run into censorship trouble. Also the English office was very concerned about an anti-Hitler picture and doubted whether it could be shown in Britain. But I was determined to go ahead, for Hitler must be laughed at. Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis. However, I was determined to ridicule their mystic bilge about a pure-blooded race.

(6) Charlie Chaplin, speech included in the Great Dictator that reflected his own views on the political situation in 1939.

The way of life can be free and beautiful, but we have lost the way. Greed has poisoned men's souls - has barricaded the world with hate - had goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed. We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical; our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness, we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost.

Soldiers! Don't give yourself to these brutes - who despise you - enslave you - who regiment your lives - tell you what to do - what to think and what to feel! Who treat you like cattle and use you as cannon fodder. Don't give yourselves to these unnatural men - machine men with machine minds and machine hearts! You are not machines! Don't hate! Only the unloved hate - the unloved and the unnatural!

(7) In his autobiography, Charlie Chaplin includes a speech he made in San Francisco advocating Russian war relief and opening a second-front in Europe.

Comrades! And I mean comrades. I am not a Communist, I am a human being, and I think I know the reactions of human beings. The Communists are no different from anyone else; whether they lose an arm or a leg, they suffer as all of us do, and die as all of us die. And the Communist mother is the same as any other mother. When she receives the tragic news that her sons will not return, she weeps as other mothers weep. I don't have to be a Communist to know that. I have only to be human being to know that. And at this moment Russian mothers are doing a lot of weeping and their sons a lot of dying.

Money will help, but they need more than money. I am told that the Allies have two million soldiers languishing in the North of Ireland, while the Russians alone are facing about two hundred divisions of Nazis. The Russians are our allies, they are not only fighting for their way of life, but for our way of life and if I know Americans they like to do their own fighting. Stalin wants it, Roosevelt has called for it - so let's all call for it - let's open a second front now!

(8) Charlie Chaplin, speech at Madison Square Park, New York (22nd July, 1942)

On the battlefields of Russia democracy will live or die. The fate of the Allied nations is in the hands of the Communists. If Russia is defeated the Asiatic continent - the largest and richest of this globe - would be under the domination of the Nazis. With practically the whole Orient in the hands of the Japanese the Nazis would then have access to nearly all the vital materials of the world. What chance would we have then of defeating Hitler?

The Russians are in desperate need of help. They are pleading for a second front. Among the Allied nations there is a difference of opinion as to whether a second front is possible now. We hear that the Allies haven't sufficient supplies to support a second front. Then again we hear they have. We also hear that they don't want to risk a second front at this time in case of possible defeat. That they don't want to take a chance until they are sure and ready.

But can we afford to wait until we are sure and ready? Can we afford to play safe. There is no safe strategy in war. At this moment the Germans are 35 miles from the Caucasus. If the Caucasus is lost 95 per cent of the Russian oil is lost. If the Russians lose the Caucasus it will be the greatest disaster of the Allied cause. Then watch out for appeasers, for they'll come out of their holes. They will want to make peace with a victorious Hitler.

(9) Three times Charlie Chaplin's appearance before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. After the third cancellation Chaplin wrote a letter to the HUAC.

For your convenience I will tell you what I think you want to know. I am not a Communist, neither have I ever joined any political party or organization in my life. I am what you call a "peace-monger". I hope this will not offend you. So please state definitely when I am to be called to Washington.

(10) Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (1964)

Friends have asked how I came to engender this American antagonism. My prodigious sin was, and still is, being a non-conformist. Although I am not a Communist I refused to fall in line by hating them.

Secondly, I was opposed to the Committee on Un-American Activities - a dishonest phrase to begin with, elastic enough to wrap around the throat and strangle the voice of any American citizen whose honest opinion is a minority of one.