Bay of Pigs

The main political issue during the 1960 Presidential Election was the government established by Fidel Castro in Cuba. On 9th January, 1960, Vice President Richard Nixon had lunch with William Pawley, who was a close friend and business associate of Fulgencio Batista, the former dictator of Cuba. Nixon regarded Pawley as his main adviser on Latin America. During the lunch they spoke about the situation in Cuba and Nixon suggested that Pawley invited President Dwight Eisenhower for a weekend of hunting at his Virginia farm. (1)

On 14th January, 1960, the National Security Council reviewed its policy on Cuba and Livingston T. Merchant of the State Department explained that his agency was "cooperating with CIA in action (redacted) designed to build up an opposition to Castro". The NSC members discussed different legal bases for intervention. Nixon, who had already been selected as the Republican Party candidate for the 1960 Presidential Election, urged the overthrow of Castro. (2)

Three days later President Eisenhower had meetings to discuss proposals for covert action in Cuba. He told two NSC staffers to meet Pawley. Five days later, Pawley called one of his CIA contacts to report that Matthew Slepin, chairman of the Dade Country Republican Party, had promised twelve Cuban exiles either $20 million or $200 million on behalf of Vice President Nixon to finance the overthrow of Castro. (3)

President Eisenhower was not in total agreement with Nixon on the plan against Castro. In a press conference held on 22nd January he claimed that the United States was continuing to prevent aggressive acts against Castro mounted from within U.S. territory, and it recognized Cuba's right to undertake domestic reforms. He also confirmed that "the policy of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other countries, including Cuba." (4) In July 1960, JMWAVE, the CIA station in Miami, Florida, began training a couple of hundred Cubans in counter-intelligence, in order to develop the nucleus of a post-Castro security organization in Havana. The head of the station was Ted Shackley, whose nickname was the "Blond Ghost" (because he hated to be photographed) became involved in CIA's Black Operations. Shackley was also closely associated with William Pawley and Eddie Bayo, the founder of Alpha 66. (5) Allen W. Dulles, the director of the CIA, put Richard Bissell, Deputy Director for Plans, in charge of this anti-Cuba task force. Later that month Dulles arranged for John F. Kennedy to meet the four leaders of the anti-Castro organization, Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front (FRD). "The purpose was to inform Kennedy of the plans that were underway to bring down the Cuban Revolution and to introduce him to the future leaders of the neighboring country." (6) As David Corn, the author of Blond Ghost: Ted Shackley and the CIA's Crusades (1994) has pointed out: "Agency officials... plotted fanciful schemes against Castro. The brainstorming was extreme. One imaginative CIA thinker proposed spraying Castro's broadcasting studio with a hallucinogenic chemical. The geniuses of the Technical Services Division (TSD) produced a box of cigars treated with a substance that would lead a smoker to become temporarily disoriented... In the summer of 1960, the craftsmen of TSD contaminated a box of Castro's favorite cigars with a lethal toxin. But the cigars never made it to Castro." (7) In September 1960, Bissell and Dulles, initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro. Robert Maheu, a private investigator and occasional CIA operative, in a conspiracy to spike Castro's food with poison. The plan was abandoned when Castro stopped visiting the Havana restaurant where he was to be poisoned. (8) According to an investigation carried out by Frank Church and his United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities in 1976, there were during a five year period when there was "concrete evidence of at least eight plots involving the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro". (9) After a newspaper report by Drew Pearson that appeared on 3rd March, 1967, about these assassination plots, President Lyndon Johnson, ordered Richard Helms, the Director of the CIA, for a detailed account of the CIA's plots to assassinate Castro. The completed report was delivered to Johnson on 10th May, 1967. Johnson later commented to a friend: "We were running a damn Murder Incorporated in the Caribbean." (10) Richard Nixon was angry with the CIA for briefing John F. Kennedy about how the United States was falling dangerously behind the Soviets in the nuclear arms race during the election campaign. (11) This put Nixon on the defensive, as did Kennedy's clarion call to support Cuban "freedom fighters" in their crusade to take back the island from Castro. This put Nixon in a very difficult position because he could not tell the public that he had already told the CIA he supported their secret plan to invade Cuba. (12) Kennedy brought this issue up during the fourth and final presidential television debate in the campaign. Richard Nixon wrote in his memoirs: "I had no choice but to take a completely opposite stand and attack Kennedy's advocacy to open intervention in Cuba. I shocked and disappointed many of my own supporters... In the debate, Kennedy conveyed the image - to 60 million people - that he was tougher on Castro and communism than I was." (13) Kennedy won a narrow victory in November, 1960. Some of Kennedy's liberal supporters like John Kenneth Galbraith, the economist, worried about the consequences of promising to help free Cuba. Kennedy had "succeeded in banishing the Democrats' image of Stevensonian weakness and replacing it with a vigorous new muscularity". The hawks now expected the new president to deliver. One of Kennedy's advisors, Harris Wofford, commented: "He had one hand in the cold war and one foot in a new world he saw coming; one hand in the old politics he had begun to master, one in the new politics that his campaign had invoked." (14) Dwight D. Eisenhower made his last speech as president on 17th January, 1961. Probably the most controversial speech of his career he gave the American people a serious warning about the situation that faced them: "Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations. This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence - economic, political, even spiritual - is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist." (15) It has been claimed that Eisenhower's military-industrial complex speech was a warning to Kennedy about the real sources of power in the United States and the pressure he had been under to order an armed invasion of Cuba. Senior figures in the CIA believed that Kennedy would support their plans for dealing with Castro. The journalist, Joseph Alsop, arranged for Kennedy to meet Richard Bissell, the CIA officer in charge of this anti-Cuba task force. Bissell later wrote: "I found Kennedy to be bright, and he raised a number of topics on which I had something to say... I told him truthfully (although perhaps a little inappropriately since I was part of the current administration) that I agreed with most of his philosophy." (16) A few days after Kennedy's victory, Bissell wrote to his close friend Edmond G. Thomas: "I am glad it came out as it did. I found less to choose between the two candidates than many of my friends, but I think Kennedy is surrounded by a group of men with a much livelier awareness than the Republicans of the extreme crisis that we are living in... What I really mean is that the Democrats will be far less inhibited in trying to do something about it. My guess is that Washington will be more lively and interesting place in which to live and work." (17) In December, 1960, Bissell received a disturbing intelligence report, Prospects for the Castro Regime. It claimed that Castro remained "firmly in control" of Cuba and that "internal opposition" was "still generally ineffective". It also noted that although anti-Castro guerrilla groups were operating in the Escambray Mountains region and in the Oriente province, the "regime has reacted vigorously and has thus been able to contain" them. The report concluded that Castro would continue to consolidate his control over Cuba: "Organized opposition appears to lack the strength and coherence to pose a major threat to the regime, and we foresee no development in the internal political situation which would be likely to bring about a critical shift of popular opinion away from Castro." (18) The CIA plan to invade Cuba, code-named JMARC (the Pentagon called it Operation ZAPATA), landed on John Kennedy's desk before he was sworn in as president. Bissell and the Director of the CIA, Allen W. Dulles briefed the president-elect on the project on 18th November, 1960. Bissell was later to recall that he was struck by Kennedy's impassiveness. "He seemed neither for nor against the operation. He expressed surprise only at the scale of it.... What had begun in the spring of 1960 as a plan to infiltrate a few dozen commandos to slip into the jungle and join the resistance had become by November a full-scale invasion - several hundred men storming a beachhead, backed up by air support." (19) Bissell told President Kennedy and Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State, of the operational plan and described how the Cuban exiles (Brigade 2506) would land and secure a beachhead close to a town named Trinidad, on the southern shore of the island some 350 miles from Havana. Rusk objected at once. He said that attempting a landing near a big town like Trinidad would inevitably attract a great deal of publicity. He was not enthusiastic about the operation at all, but if it did not have to take place, he insisted on a more obscure landing place as it would look like a genuine guerilla operation. Bissell was also unable to guarantee that the invasion would definitely result in the overthrow of Castro. Bissell said: "We have reports it will, but how can you possibly tell?" (20) Those involved in the CIA operation to overthrow Castro included David Sanchez Morales, Henry Hecksher, William Harvey, David Atlee Phillips, Ted Shackley, E. Howard Hunt, Desmond FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes and William (Rip) Robertson. An interesting recruit was Carl E. Jenkins. According to Larry Hancock, "Jenkins came into the Cuba project in 1960 and served with it until the Bay of Pigs; he performed selection and training of paramilitary cadre, selected officers, and managed small teams and individual agents in maritime infiltration of Cuba." (21) Kennedy was deeply ambivalent about the Cuban operation. In March, 1961, he held a reception he for Latin American Diplomats and Members of Congress. In his speech he launched the proposed Alliance for Progress with Central and South America. "We meet together as firm and ancient friends, united by history and experience and by our determination to advance the values of American civilization. For this new world of ours is not merely an accident of geography. Our continents are bound together by a common history - the endless exploration of new frontiers. Our nations are the product of a common struggle - the revolt from colonial rule. And our people share a common heritage - the quest for the dignity and the freedom of man.... As a citizen of the United States let me be the first to admit that we North Americans have not always grasped the significance of this common mission, just as it is also true that many in your own countries have not fully understood the urgency of the need to lift people from poverty and ignorance and despair. But we must turn from these mistakes - from the failures and the misunderstandings of the past - to a future full of peril but bright with hope.... And if we are successful, if our effort is bold enough and determined enough, then the close of this decade will mark the beginning of a new era in the American experience... every American Republic will be the master of its own revolution and its own hope and progress." (22) Kennedy realised that the Alliance for Progress would not get off to a very good start if the United States used a CIA backed force to overthrow the Cuban government. Kennedy was also worried that if he went after Castro, Nikita Khrushchev might make a move against Berlin. On the other hand, he did not want to blamed by members of the Republican Party for "chickening out" or going soft on communism. Kennedy therefore decided "to take half measures in and all-or-nothing situation." (23) On 3rd April, 1961, Kennedy met secretly with a dozen of his top advisers. He also brought with him Senator William Fulbright, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Fulbright made a moral argument against the United States sponsoring secret invasions of other countries. His contribution upset others in the room. Some, like Paul Nitze, the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, found themselves voting for the invasion, not because they really believed in it, but because they disliked Fulbright's arguments. Adolf Berle, the State Department specialist on Latin America, cried out, "I say, let 'er rip!" (24) Bissell was encouraged by the meeting. He felt he had finally been given approval, although Kennedy reserved the right to make a final decision on the eve of the invasion. However, Bissell was worried by Kennedy's attitude towards the invasion. "Without anyone's realizing it, however, there was something of an undercurrent in the government that was serving to undermine what chances the operation had... On at least two occasions (reported to me by eyewitnesses), some of the Joint Chiefs said they felt the CIA was exaggerating the need for air cover for the landing... I was shocked. We all knew only too well that without air support the project would fail." (25) Kennedy told Bissell that it was vitally important that the United States government could not be connected to the invasion of Cuba. Bissell tried to change his approach by approaching the president's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Bissell said that without air cover the odds of success as only two out of three. Soon afterwards, the New York Times reported that the United States was training Cuban exiles for an imminent invasion. Kennedy feared that the CIA was leaking information to the press. He told his press secretary, Pierre Salinger: "I can't believe what I'm reading! Castro doesn't need agents over here. All he has to do is read our papers." (26) David Atlee Phillips and Tracy Barnes developed an elaborate cover story to give the impression that the air strikes on Cuba would to be an inside job - originating from Cuba, not from the CIA's secret air base in Nicaragua. After the raid a pair of B-26s would land in Florida, piloted by Cubans claiming to be defectors. They would tell newsmen that they had bombed and shot up their own airfields on the flight to freedom. On Saturday morning, 15th April, 1961, eight B-26s out of Nicaragua, manned by Cuban pilots, bombed three of Castro's airfields. After the air raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. (27) Later that day Raúl Roa García, the Cuban foreign minister, demanded the floor of the United Nations General Assembly to declare that his country had been bombed by U.S. aircraft. Adlai Stevenson, the U.S. representative, held up a photograph of one of the planes that had landed in Florida. "It has the markings of Castro's air force on the tail, which everyone can see for himself. The Cuban star and the initials F.A.R., Fuerza Aerea Revolucionaria, are clearly visible." Phillips watched the speech on television and commented "what a smooth phony he is". Then it occurred to him that Stevenson didn't know the truth and had not been full briefed by Tracy Barnes about the operation. (28) The cover story began to peel away almost immediately. As Terence Cannon pointed out: "Nine CIA planes had taken off that morning from Puerto Cabezas (Nicaragua): eight for Cuba and one directly to Miami... each plane bore an imitation of the Cuban Air Force insignia. The single pilot bound for Miami was to arrive there just after the others had bombed Cuba... An enterprising reporter got close enough to his plane to notice that dust and grease covered the bomb-bay doors and that the muzzles of the guns were taped shut. The plane had obviously not participated in any attack." (29) Stevenson was furious as he felt that he had been "deliberately tricked" by his own government and sent a cable to Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State: "I had definite impression from Tracy Barnes when he was here that no action would be taken which could give us political difficulty during current U.N. debate.... I do not understand how we could let such an attack take place two days before debate on Cuban issue in the General Assembly. Nor can I understand, if we could not prevent such an outside attack from taking place at the time, why I could not have been warned." (30) On 17th April, five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles headed for the Bay of Pigs. The director of the CIA, Allen W. Dulles was in Puerto Rico during the invasion. He left Charles Cabell in charge. Instead of ordering the second air raid he checked with Dean Rusk. He contacted Kennedy who said he did not remember being told about the second raid. After discussing it with Rusk he decided to cancel it. Instead the operation tried to rely on Radio Swan, broadcasts being made on a small island in the Caribbean by David Atlee Phillips, calling for the Cuban Army to revolt. They failed to do this. Instead they called out the militia to defend the fatherland from "American mercenaries”. (31) At 6:30 a.m. one of the Brigade 2506's landing ships, the Houston, was hit at the waterline by a rocket fired from Cuba. The ship quickly began to sink. At 9:30 a.m. a second ship of the invasion force, the Rio Escondo, went up in a giant fireball. Castro's planes had hit 200 hundred barrels of aviation fuel. A communications van sank with the ship, cutting off any air-land radio contact. Castro also deployed columns of soldiers and tanks to resist the invasion. By Monday afternoon, the battle had clearly turned against the Brigade. (32) Richard Bissell later wrote: "The president's decision to cancel the D day air strikes, the limited availability of aircraft and crews, and an air arm forbidden by the president to engage in strategic bombing meant that some of Castro's air force survived and sank two supply ships. This was a turning point for the brigade since the remainder of the supply ships withdrew to a position some fifty miles offshore, where they were presumably out of range of further attack but unavailable to give logistical support. Without resupply and air cover, the venture was doomed." (33) Richard Helms, who was to replace Bissell as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Plans, also blamed President Kennedy for the Bay of Pigs disaster. "The ZAPATA Brigade force seized a beachhead along the Bay of Pigs - the original and more feasible landing area having been vetoed by President Kennedy. Two days and some hours later, the surviving 1189 members of the attack force were still contained within the beachhead. After President Kennedy refused to provide the desperately needed additional air support and their ammunition was almost exhausted, the men had no choice but to surrender." (34) Ted Shackley, another senior figure in the CIA involved in the operation, pointed out: "Covert action is not a weapon that intelligence services can wield at will. Spymasters may be called upon to help kings and field marshals with their intrigues, but the latter call the shots. And a corollary to this is that no covert-action operation mounted by an intelligence service has much chance of success if it is not solidly supported at the highest levels of government and coordinated with the leadership's other means of persuasion - diplomatic, military and propagandistic." (35) On 20th April, 1961, Bissell told President Kennedy that the Brigade was trapped on the beaches and encircled by Castro's forces. Bissell asked for United States air support but Kennedy replied that he still wanted "minimum visibility". At 2:32 on Wednesday afternoon Pepe San Román, the Brigade's commander, reported that Castro's tanks were breaking through. His last message was "Am destroying all equipment and communications. I have nothing left to fight with. Am taking to the swamps. I can't wait for you." To his CIA handler, safely aboard ship, he had a last farewell: "And you, sir," he said, "are a son of a bitch." (36) President Kennedy had presided at all the discussions, and from the moment the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave the operation their approval, he had given it his full presidential backing. On 21st April, Kennedy admitted blame for the failed Bay of Pigs invasion: "There's an old saying that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan ... Further statements, detailed discussions, are not to conceal responsibility because I'm the responsible officer of the Government." (37) An estimated 67 Cuban exiles from Brigade 2506 were killed in action. Aircrews killed totaled 6 from the Cuban air force, 10 Cuban exiles and 4 American airmen. This included Thomas Ray, a CIA officer. The final toll in Cuban armed forces during the conflict was 176 killed in action. This figure includes only the Cuban Army and it is estimated that about 2,000 militiamen were killed or wounded during the fighting. The airfield attacks on 15 April left 7 Cubans dead and 53 wounded. (38) The Cuban government carried out a detailed investigation into the 1,197 captured troops. It was claimed they were composed of: 100 plantation owners, 67 landlords of apartment houses, 24 large property owners, 112 businessmen, 194 ex-soldiers of Batista (including 14 wanted for murder and torture during the revolutionary war), 179 "idle rich" and 35 industrial magnates. Together they owned 923,000 acres of land, 9,666 houses and apartment buildings, 70 factories, 10 sugar mills, 3 banks, 5 mines and 12 nightclubs. (39) However, behind the scenes, it was decided that the director of the CIA, Allen W. Dulles, should take most of the blame for the failed operation. President Kennedy suggested Dulles should resign. He refused claimed that Robert Kennedy was the one to go as he had been the main figure calling on Castro to be removed. Eventually it was agreed that Dulles should stay on for a few months and that his resignation would not seem like a sacking for his role in the Bay of Pigs disaster. John McCone replaced him on 29th November, 1961. (40)CIA Operations in Cuba

1960 Presidential Election

Operation ZAPATA

The Bay of Pigs Invasion

Primary Sources

(A1) In 1953, Fidel Castro complained about Cuba's economic relationship with the United States.

With the exception of a few food, lumber and textile industries, Cuba continues to be a producer of raw materials. We export sugar to import candy, we export hides to import shoes, we export iron to import ploughs.

(A2) After Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union met Fidel Castro in New York in 1960 he told a colleague what he thought of him.

Castro is like a young horse that hasn't been broken. He needs some training, but he's very spirited - so we will have to be careful.

(A3) In his book The Perfect Failure, Trumbull Higgins argues that Kennedy had a strong dislike of Fidel Castro and had been discussing his removal even before he became president.

As early as October 1960 Kennedy had discussed with his conservative friend Senator George Smathers of Florida the likely reaction of the American public to an attempt to assassinate Castro. Alternatively, Kennedy and Smathers had considered provoking a Cuban assault upon the base at Guantanamo to provide an excuse for a U.S. invasion of the island.

(A4) Terence Cannon was born in the United States but in the 1960s lived and worked in Cuba. In his book, Revolutionary Cuba, Cannon discusses the air-raid on Cuba on 14th April, 1961.

Nine CIA planes had taken off that morning from Puerto Cabezas (Nicaragua): eight for Cuba and one directly to Miami... each plane bore an imitation of the Cuban Air Force insignia. The single pilot bound for Miami was to arrive there just after the others had bombed Cuba... An enterprising reporter got close enough to his plane to notice that dust and grease covered the bomb-bay doors and that the muzzles of the guns were taped shut. The plane had obviously not participated in any attack.

(A5) Peter Bourne worked as an assistant to President Jimmy Carter. After meeting Fidel Castro in 1979 he decided to write a book about him. In the book he dealt with the Bay of Pigs incident.

One plane that took off from Nicaragua with the others did not engage in the raid, but flew to Miami with an engine deliberately feathered by pistol shots. When it landed, the pilot claimed that he was a member of Fidel's air force who had defected after bombing his own airfield... Knowledgeable journalists noticed that his B-26 had a metal nose cone while those in the Cuban air force were made of Plexiglass.

(A6) After the bombing raid on 14th April 1961, Fidel Castro made a speech to the Cuban people.

The imperialists plan the crime, organize the crime, furnish the criminals with weapons for the crime, pay the criminals, and then those criminals come here and murder the sons of seven honest workers. Why are they doing this? They can't forgive our being right under their very noses, seeing how we have made a revolution, a socialist revolution. Comrades, workers and peasants, this is a socialist and democratic revolution of the poor, by the poor and for the poor, we are ready to give our lives.

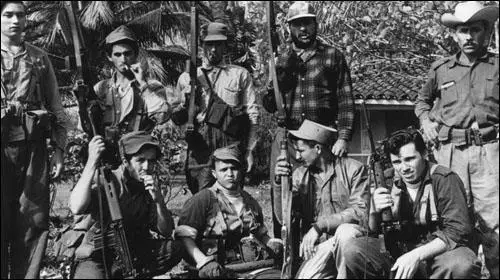

(A7) In 1961 the Cuban government published details of some of the 1,197 prisoners Involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Occupations: 100 plantation owners; 67 landlords of apartment houses; 35 factory owners; 112 businessmen; 179 lived off unearned income; and 194 ex-soldiers of Batista.

Total property owned in Cuba: 923,000 acres of land; 9,666 houses and apartment buildings; 70 factories; 12 night clubs; 10 sugar mills; 24 large property owners; 5 mines and 3 banks.

(A8) On February 4,1962 Fidel Castro made a speech in Havana where he considered the motivations behind the Bay of Pigs invasion.

What is hidden behind the Yankee's hatred of the Cuban Revolution... a small country of only seven million people, economically underdeveloped, without financial or military means to threaten the security or economy of any other country? What explains it is fear. Not fear of the Cuban Revolution but fear of the Latin American Revolution.

(A9) After the Bay of Pigs, Philip Bonsol, the United States Ambassador in Cuba, wrote about the failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro .

The Bay of Pigs was a serious setback for the United States... It consolidated Castro's regime and was a determining factor in giving it the long life it has enjoyed... It became clear to all concerned in Washington, in Havana and in Moscow that for the time being the Castro regime could be overthrown only through an overt application of American power.

(A10) E.Howard Hunt, interviewed for the television programme, Backyard (21st February, 1999)

When I came back (from Cuba), I wrote a top secret report, and I had five recommendations, one of which was the one that's always been thrown at me, is that during... or... slightly antecedent to an invasion, Castro would have to be neutralized - and we all know what that meant, although I didn't want to say so in a memorandum with my name on it. Another one was that a landing had to be made at such a point in Cuba, presumably by airborne troops, that would quarter the nation, and that was the Trinidad project; cut the communications east to west, and there would be confusion. None of that took place. Once, when I came back from Coconut Grove and said, "What about... is anybody going after Castro? Are you going to get rid of him?", "It's in good hands," was the answer I got, which was a great bureaucratic answer. But the long and the short of it was that no attempt that I ever heard of was made against Castro's life specifically. President Idigros Fuentes of Guatemala was good enough to give our Cuban exiles two training areas in his country, one in the mountains, and then at (Retardo Lejo) we had an unused airstrip that he gave over to us, which we put into first-class condition for our fighter aircraft and our supply aircraft, and we trained Cuban paratroopers there. And the brigade never numbered more than about 1,500, which was 10 times more than Castillo Armas commanded.

(A11) Chauncey Holt was interviewed by John Craig, Phillip Rogers and Gary Shaw for Newsweek magazine (19th October, 1991)

We went to Cuba many times. At that point in time Carlos Prio was President of Cuba and Batista was in exile. It was Lanksy who was instrumental in getting Prio to allow Batista back into the country. He came back into the country and one day he just walked into the Presidential Palace apparently, and made Prio an offer he couldn't refuse... Batista was always in Lansky's pocket. So we were back and forth there in regards to the casinos.

Later on, when Castro started kicking up a force, and of course after he had landed there in the Escambay Mountains, Lansky, to hedge his bet, began offering assistance to Castro in the form of money and arms that were flying in. So although he was a very close friend of Batista, he was still assisting Castro. Around that time flying arms to Castro was no problem. The State Department didn't bother you at all. They just tolerated it.