William Orpen

William Orpen, the son of Arthur Herbert Orpen, a solicitor, was born in Stillorgan on 27th November 1878. Orpen showed an early interest in drawing and according to his biographer this "was indulged by his mother, who supported his wish to go to art school against her husband's desire that he should study law and enter the family firm."

Orpen entered the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin at the age of thirteen. During his years at the school Orpen won every major prize available. He then enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1897. His main tutors were Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer. Orpen's fellow students included Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis. Spencer Gore, Michel Salaman, Edna Waugh, and Herbert Barnard Everett.

Initially, Orpen wanted to be a caricaturist but after having several cartoons rejected by Punch Magazine he decided to return to Ireland to teach at the Dublin School of Art. He returned to London in 1903 where he joined forces with Augustus John to run a short-lived art school in Chelsea. In 1906 he also helped to set up the Chenil Gallery with his brother-in-law, Jack Knewstub.

In 1908 Orphen exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy. This helped to develop his reputation as a portrait painter. In 1916 Orpen's friend, the Quartermaster General, John Cowans, arranged for him to receive a commission in the Army Service Corps. This mainly involved him painting the portraits of senior political and military figures such as Winston Churchill and Lord Derby.

In early 1917, Charles Masterman, head of the government's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB) recruited Orpen to produce paintings of the Western Front. His biographer, Bruce Arnold, points out: "He left for France in April 1917, and for the next four years was totally immersed in the war and its aftermath. His output, and its overall excellence, makes him the outstanding war artist of that period, possibly the greatest war artist produced in Britain. Analysis of his war work, the major part of which is in the Imperial War Museum, London, shows a development in style and understanding, from the idealism which inspired him when he first arrived at the front to the disillusionment with the terrible ending to the war, and then the further dismay he and many felt at the direction taken by the peace deliberations. His paintings of the Somme battlefields are haunting recollections of anguish and chaos, of ruined landscapes baked in the summer sun, the torn ground white and rocky, the debris of the dead scattered and ignored."

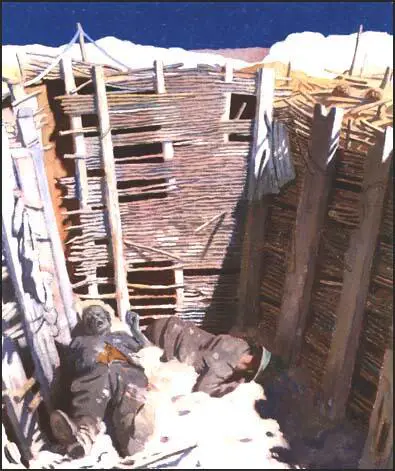

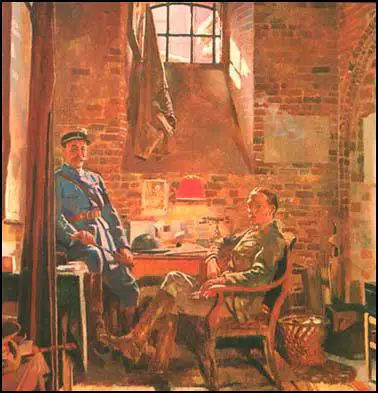

While in France he painted portraits of Sir Douglas Haig, Hugh Trenchard, Herbert Plumer, Henry Rawlinson, Henry Wilson, James McCudden, Arthur Rhys-Davids, Reginald Hoidge, John Edward Seely, John Cowans, Adrian Carton de Wiart, and Ferdinand Foch. Orpen was shocked by what he saw at the front and also painted pictures such as Dead Germans in a Trench. Other paintings such as The Mad Woman of Douai, "convey the stress and anguish he certainly felt about the war and its aftermath".

Orpen was commissioned to paint portraits of the politicians at the Versailles Peace Conference. He also produced a series of caricatures that according to the author of the Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Cartoonists and Caricaturists (2000) "were widely admired". Orpen believed that the soldiers that fought in the war were betrayed by the politicians at Versailles. Instead of the portraits he painted To the Unknown British Soldier in France. The original painting showed the draped coffin flanked by two shell-shocked soldiers standing guard. There was such an outcry when it was exhibited in 1919 that Orpen was forced to paint out the soldiers. However, as one critic has pointed out "their shadowy forms remaining as ghostly pentimento."

Orpen wrote about his experiences in the First World War in An Onlooker in France (1921). Bruce Arnold has argued: "His outspokenness became controversial. His standing as a painter gave him the ear of many people in power, and he took risks, confronting what he saw as foolishness.... His own personality had developed with the war; his early idealism became a form of sombre realistic recognition of the terrible path of war through the lives of a whole generation. He came to love the fighting man, and to despise the politicians, with their glib words and their self-interested carve-up of Europe which was subsequently to prove so disastrous."

An exhibition of Orpen's war paintings were well received. Arnold Bennett argued: "William Orpen, having discovered a new subject, composes it newly.... Landscape, shell-holes, ruined trees and buildings, dug-outs, tents, and the tragedy and comedy of human existence - he see them as though nobody had ever seen them before; and he arranges them in fresh patterns of contour, colour, plane. His ingenuity in manipulating the material is simply endless, and yet he is never tempted to falsify the material."

Orphen became known for his portraits of public figures and during his career produced over 600 of these pictures. Mark Bryant has pointed out: "However, though he was financially very successful in his main occupation as a portrait painter (reputedly earning more than £54,000 in 1929 alone) his technique of using photographs as an aid did not meet with universal approval."

Sir William Orpen died from liver and heart failure on 29th September 1931 at his home in South Kensington. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery.

Primary Sources

(1) William Orpen, letter to Grace Orpen (15th April 1917)

I cannot describe the impression I have formed from what I have already seen - that such a machine has been going on in over 2 years and growing bigger everyday is past comprehension, it makes one look on human beings as a different breed than one had ever imagined them before, the nobility and self sacrifice are beyond understanding. The whole thing is fine noble and bold.

Of course there is the other side, today when I had finished work, I went over some country that was really terrible, it was fought over last about 3 weeks ago, everything is left practically as it was, they have now started to bury the dead in some parts of it Germans and English mixed, this consists of throwing some mud over the bodies as they lie, they don't even worry to cover them altogether arms and feet showing in lots of cases.

The whole country is obliterated. In miles and miles nothing left at all except shell holes full of water you pick your way between them or jump at times, miles and miles of shell holes bodies rifles steel helmets gas helmets and all kinds of battered clothes, German and English, dud shells and wire, all and everything white with mud, and one feels the horrors the water in the shell holes is covering - and not a living soul anywhere near, a truly terrible peace in the new and terribly modern desert - it was a relief to get back to the road and people.

The roads behind the line are wonderful one moving mass of men, horses, mules, ammunition, guns food, fodder, pontoons and every imaginable kind of war material all struggling in one steady stream up these battered thoroughfares, all white with mud halting and struggling on again at regular intervals it is a wonderful sight full of grim determination.

(2) William Orpen, letter to Grace Orpen (15th May 1917)

I am going over tomorrow to GHQ to do a little sketch of Haig, it will be nervous work and I would much sooner be drawing his men - they are the most wonderful creatures - and sit in the most splendid way better than any pro.

(3) William Haig, diary (11th May 1917)

Major Orpen, the artist, came to lunch. I told him that every facility would be given him to study the life and surroundings of our troops in the field, so that he can really paint pictures of lasting value. The War Office already wanted to see the results of his labours in return for the pay which he is now receiving! As if he were a sausage machine into which so much meat is put and the handle is turned and out come the sausages! But war is a fickle mistress!

(4) Arnold Bennett, comment on William Orpen's paintings (May 1918)

William Orpen, having discovered a new subject, composes it newly.... Landscape, shell-holes, ruined trees and buildings, dug-outs, tents, and the tragedy and comedy of human existence - he see them as though nobody had ever seen them before; and he arranges them in fresh patterns of contour, colour, plane. His ingenuity in manipulating the material is simply endless, and yet he is never tempted to falsify the material.

(5) The Burlington Magazine (July, 1918)

There are a great many differences of temperament and outlook among the official artists who have hitherto illustrated the war, and this variety is a distinct advantage from the point of view of a pictorial record. The imaginative, generalizing vision naturally lays stress on aspects differing from those selected by a more literal realism. Each has its separate value, and helps to make the collection of historical documents more complete. Sir William Orpen's contribution to the record is an important one. In some degree he fuses the imaginative tendency with the literal. He excels in exact delineation - in the rapid notation of the thing seen.... There is in his exhibition an impression of work done at high pressure, but the keen discipline of hand and eye is never relaxed.... The quality of precision, together with a quick-witted appreciation of character and incident, is found in almost all the paintings and drawings... Apart from literal representation, Sir William Orpen has a piquant sense of the grotesque-romantic, which never deepens into real tragedy, but has a curious and quite personal turn.

(6) Ezra Pound, The New Age (18th July, 1918)

The Orpen show need not detain one - Slade, Slade Sketch Club, Society tinted-photos. Are the generals in tents or in Mayfair? In short, Sir William's message is that the war is very like peace-life Belgravia - bright cheery tints, lemonish egg-yolk yellow. Any tone of war, any feeling of war, wholly absent - the usual pre-War Orpen drawings rather more hastily done. Ease, comfort, complexion soap, a little stage decoration. A pale cast of prettiness.

(7) Lord Beaverbrook, quoted in The Times (24th May 1918)

In conversation it was discovered, almost by chance, that Major Orpen intended to present his whole collection to the nation. This was a very remarkable decision. Men had been known to give picture galleries to the nation; artists had been known to give pictures to the nation; but, he thought, perhaps this was the only occasion on which an artist had given all the results of two years of labour - given them up quite freely and as a matter of course. He was sure that in the hearts of all there was a real, deep and lasting feeling of gratitude to Major Orpen.

(8) John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters (1976)

The only occasion when I can recall his speaking with vehemence upon a serious theme was one night in 1920 when we were sitting alone after dinner at his house. He talked, more than he habitually talked, incoherently and faster, about the sickening impact of the callousness and the petty self-interest of the peace-makers in Paris, above all their forgetfulness of the millions of mangled, rotting corpses in the Flanders slime. He (William Orpen) took out of his pocket a copy of Maurice Baring's poem 'In Memoriam' to his friend Lord Lucas, which he read out, his jerky diction obscuring its qualities as a poem, but giving an enhanced intensity to its meaning. "This poem", he declared, "is the greatest work of art that's come out of this whole war." I got Maurice Baring to copy it out for me. Maurice Baring said to me: "I'm mad, but nobody's noticed it yet". That's true of us all: the whole world's mad.

(9) Sidney Dark, Sir William Orpen: Artist and Man (1932)

He came back from Paris to have twelve years of supreme success. But I do not think it is to be denied that, to an increasing extent, the success was a Dead Sea apple in his mouth .... Orpen, I am convinced, was always trying to "laugh it off". His war experiences had bitten into his soul. He was obsessed by the bitterness, futility, the cruelty of life.

(10) William Orpen, An Onlooker in France (1921)

May-June 1917: What a life! Twenty-four hours of it was enough for me at a time. Before evening came my head felt as if it were filled with pebbles which were rattling about inside it. After lunch I sat with the Brigadier for a time and watched the men coming out from the trenches. Some sick; some with trench feet; some on stretchers; some walking; worn, sad and dirty - all stumbling along in the glare. The General spoke to each as they passed. I noticed that their faces had no change of expression. Their eyes were wide open, the pupils very small, and their mouths always sagged a bit. They seemed like men in a dream, hardly realising where they were or what they were doing. They showed no sign of pleasure at the idea of leaving Hell for a bit. It was as if they had gone through so much that nothing mattered. I was glad when I was back at Divisional HQ that evening. We had difficulty on one part of the road, as a barrage ballon had been brought down across it.

(11) William Orpen, An Onlooker in France (1921)

Sir Douglas Haig was a strong man, a true Northerner, well inside himself - no pose. It seemed it would be impossible to upset him, impossible to make him show any strong feeling, and yet one felt he understood, knew all, and felt for all his men, and that he truly loved them; and I knew they loved him. Never once, all the time I was in France, did I hear a "Tommy" say one word against Haig. Whenever it became my honour to be allowed to visit him, I always left feeling happier - feeling more sure that the fighting men being killed were not dying for nothing. One felt he knew, and would never allow them to suffer and die except for final victory.

When I started painting him he said, "Why waste your time painting me? Go and paint the men. They're the fellows who are saving the world, and they're getting killed every day."

(12) William Orpen, An Onlooker in France (1921)

The Ypres Salient - June 1917: Here the Press used to come when any particular operation was going on in the North. In my mind now I can look clearly from my room across the courtyard and can see Beach Thomas by his open window, in his shirt-sleeves, writing like fury at some terrific tale for the Daily Mail. It seemed strange his writing this stuff, this mild-eyed, country-loving dreamer; but he knew his job.

Philip Gibbs was also there - despondent, gloomy, nervy, realising to the full the horror of the whole business; his face drawn very fine, and intense sadness in his very kind eyes; also Percival Phillips - that deep thinker on war, who probably knew more about it than all the rest of the correspondents put together... According to Beach Thomas, "The censors would not publish any article if it indicated that the writer had seen what he wrote of. He must write what he thought was true, not what he knew to be true."

(13) William Orpen, An Onlooker in France (1921)

General Trenchard and Maurice Baring chose out two of the leading flying boys for me to paint, and they sat to me at Cassel. One was 2nd Lieutenant A.P. Rhys Davids, DSO, MG, a great youth. He had brought down a lot of Germans, including two cracks, Schaffer and Voss. The first time I saw him was at the aerodrome at Estre Blanche. I watched him land in his machine, just back from over the lines. Out he got, stuck his hands in his pockets, and laughed and talked about the flight with Hoidge and others of the patrol, and his Major, Bloomfield. A fine lad, Rhys Davids, with a far-seeing, clear eye. He hated fighting, hated flying, loved books and was terribly anxious for the war to be over, so that he could get to Oxford. He had been captain of Eton the year before, so he was an all-round chap, and must have been a magnificent pilot. The 56th Squadron was very sad when he was reported missing, and refused to believe for one moment that he had been killed till they got the certain news. It was a great loss.

The other airman chosen was Captain Hoidge, MC and Bar - "George" of Toronto. Hoidge had also brought down a lot of Germans. His face was wonderfully fitted for a man-bird. His eyes were bird's eyes. A good lad was Hoidge, and I became very fond of him afterwards. I arranged with Maurice Baring and Major Bloomfield that Hoidge was to come to Cassel one morning at 11 am to sit to me. The morning arrived and ii o'clock and no Hoidge. 11.30, 12 - no Hoidge. About 12.30 he strolled into the yard and I heard him asking for me in a slow voice. I was raging with anger by this time. He came upstairs and I told him there was no use doing anything before lunch, and that we had better go down and get some food. We ate silently. I could see he was rather depressed. About half-way through our meal, he said: "I'm lucky to be here with you this morning!" "Why?" said I. "Oh," he said, "I made a damned fool of myself this morning. Let an old Boche get on my tail. Damned fool I was - with my experience. Never saw the blighter. I was following an old two-seater at the time. He put a bullet through the box by my head, and cut two of my stays. If old B. hadn't happened to come up and chased him off I was for it. Damned fool! But the morning wasn't wasted, afterwards I got two two-seaters." I said: "Do you realise you have killed four men this morning?" "No," he said, "but I winged two damned nice birds." Then we went upstairs and he sat like a lamb.