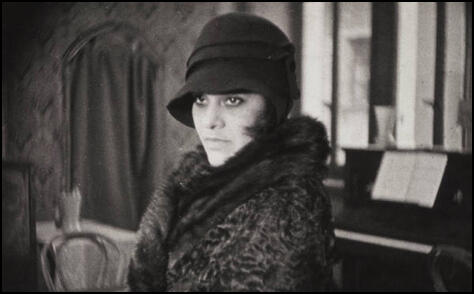

Eslanda Goode

Eslanda Goode, the daughter of John Goode and Eslanda Cardozo, was born in Washington in 1896. Her father died when she was six and the rest of the family moved to New York City.

In 1912 Goode won a four-year scholarship to the University of Illinois. After graduating in 1917, she accepted an offer as histological chemist at the Presbyterian Hospital in New York.

Goode married Paul Robeson in 1921 but continued her studies and after graduating from the University of Chicago in 1923, Goode became the first African American analytical chemist at Columbia Medical Centre. Her book, Paul Robeson, Negro, was published in 1930.

Goode became increasingly concerned with the issue of civil rights. She also became close friends with the radical political figures, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. In her autobiography Goldman wrote that "Essie (Goode) was a delightful person, and Paul (Robeson) fascinated everyone."

In 1932 Goode became her Robeson's manager and was closely associated with his various political campaigns. This included opposition to fascists in Europe and attempts to persuade Congress to pass anti-lynching legislation.

Goode and her husband, Paul Robeson, were both supporters of the Popular Front government in Spain. On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Goode was active in raising money for the International Brigades. In January 1938 Goode, Robeson joined Charlotte Haldane, Secretary of the Dependents Aid Committee, in Spain.

Eslanda Goode studied social anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science (1936-37) and in the Soviet Union at the National Minorities Institute before publishing African Journey in 1945.

Goode and Robeson's political activities led to them being investigated by House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The government decided that both were members of the American Communist Party. Under the terms of the Internal Security Act, members of the party could not use their passports. Blacklisted at home and unable to travel abroad, Robeson's income dropped from $104,000 in 1947 to $2,000 in 1950.

Both Goode and Paul Robeson opposed the Korean War and drew attention to the murders of Harriet and Harry S. Moore on 25th December, 1951, because of their attempts to establish a branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in Heartbreak Ridge in Florida. She wrote they were killed "not on Heartbreak Ridge on the distant battlefield of Korea, but on Heartbreak Ridge here in Mims, Florida." Their assassination proved, she wrote, that the world prestige of the United States was being threatened by "a few vicious, powerful active Un-Americans."

When Goode appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955 she pointed out to the senators: "You're white and I'm a Negro, and this is a very white committee." She denied being a member of the American Communist Party but praised its policy of being in favour of racial equality.

In 1958 the government lifted the ban it had imposed prohibiting the Robesons from leaving the United States. The couple moved to Europe where they lived for five years. Eslanda Goode died of cancer in 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1931 Eslanda Goode wrote down some thoughts on her relationship with Paul Robeson.

His education was literary, classical, mine was entirely scientific; his temperament was artistic, mine strictly practical; he is vague, I am definite; he is social, casual, I am not; he is leisurely, lazy, I am quick and energetic. He is genial, easily imposed upon, mildly interested in everybody and very impractical; I am pleasant to a few people, affectionately and deeply devoted to a very few, and entirely unaware that anybody else existed. Paul could be rude or say no to anyone; I could relish being rude to anyone who deserved it. He likes late hours, I am an early bird; he likes irregular meals, they are the bane of my life; he likes leaving things to chance, I like making everything as certain as possible; he is not ambitious, although once having undertaken a thing he is never content until he accomplishes it as perfectly as possible; I am essentially and aggressively ambitious, I like to undertake things.

(2) Eslanda Goode diary entries while in Spain visiting the International Brigades in January 1938.

Wednesday 26th January 1938: Back at Albacete in our so-called Grand Hotel. Off to Tarazona, the training camp for the International Brigade. Arrived about twelve, had a good lunch with the men.

Saw lots of Negro comrades, Andrew Mitchell of Oklahoma, Oliver Ross of Baltimore, Frank Warfield ofSt Louis. All were thrilled to see us and talked at length with Paul. All the white Americans, Canadians and English troops were also thrilled to see Paul.

A Major Johnson - a West Pointer - had charge of training. The officers arranged a meeting in the church and all the Brigade gathered there at 2:30 sharp, simply packing the church. But before they filed in, they passed in review in the square for us, saluting us with Salud! as they passed.

Major Johnson told the men that they are to go up to the front line tomorrow. The men applauded uproariously at that news.

Then Paul sang, the men shouting for the songs they wanted: 'Water Boy', 'Old Man River', 'Lonesome Road', 'Fatherland'. They stomped and applauded each song and continued to shout requests. It was altogether a huge success. Paul loved doing it. Afterwards we had twenty minutes with the men and took messages for their families.

Monday 31st January: We had a good talk over lunch and afterwards over coffee in the lounge, and then we went off to the border. Fernando, in civilian dress, accompanied us, and Lt. K., armed in full uniform, was our official escort.

As we drove along, Lt. K. got talking and told us the story of Oliver Law. It seems he was a Negro - about 33 - who was a former army man from Chicago. He had risen to be a corporal in the US Army. Quiet, dark brown, dignified, strongly built. All the men liked him. He began here as a corporal, soon rose to sergeant, lieutenant, captain and finally was commander of the Battalion - the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. K. said warmly that many officers and men here in Spain considered him the best battalion commander in Spain. The men all liked him, trusted him, respected him and served him with confidence and willingly.

Lt. K. tells of an incident when the battalion was visited by an old Colonel, Southern, of the US Army. He said to Law - 'Er, I see you are in a Captain's uniform?' Law replied with dignity, 'Yes, I am, because I am a Captain. In America, in your army, I could only rise as high as corporal, but here people feel differently about race and I can rise according to my worth, not according to my color!' Whereupon the Colonel hemmed and hawed and finally came out with: 'I'm sure your people must be proud of you, my boy.' 'Yes,' said Law. 'I'm sure they are!'

Lt. K. says that Law rose from rank to rank on sheer merit. He kept up the morale of his men. He always had a big smile when they won their objectives and an encouraging smile when they lost. He never said very much.

Law led his men in charge after charge at Brunete, and was finally wounded seriously by a sniper. Lt. K. brought him in from the field and loaded him onto a stretcher when he found how seriously wounded he was. K. and another soldier were carrying him up the hill to the first aid camp.

On the way up the hill another sniper shot Law, on the stretcher; the sniper's bullet landed in his groin and he began to lose blood rapidly. They did what they could to stop the blood, hurriedly putting down the stretcher. But in a few minutes the loss of blood was so great that Law died.