Mikhail Koltsov

Mikhail Koltsov, the son of a Jewish shoemaker in Kiev, was born in Russia on 31st May, 1898. He became a Bolshevik and took part in the Russian Revolution in 1917. He was a member of the Red Army that beat the White Army in the Russian Civil War. (1)

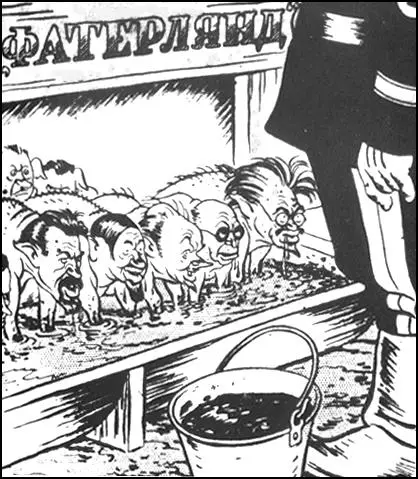

On his return to Moscow he became an important figure in the creation of a communist media in the Soviet Union. He worked for Pravda and helped to establish Krokodil. His brother, Boris Efimov, a talented cartoonist, also contributed to these journals. (2)

For a time Koltsov was a supporter of what became known as the Workers' Opposition. The leaders of this group were Alexandra Kollantai (Commissar for Welfare) and Alexander Shlyapnikov (Commissar for Labour). Kollantai published a pamphlet The Workers' Opposition, where she called for members of the party to be allowed to discuss policy issues and for more political freedom for trade unionists. She also advocated that before the government attempts to "rid Soviet institutions of the bureaucracy that lurks within them, the Party must first rid itself of its own bureaucracy." (3)

The group also published a statement on 27th February, 1921: "A complete change is necessary in the policies of the government. First of all, the workers and peasants need freedom. They don't want to live by the decrees of the Bolsheviks; they want to control their own destinies. Comrades, preserve revolutionary order! Determinedly and in an organized manner demand: liberation of all arrested Socialists and non-partisan working-men; abolition of martial law; freedom of speech, press and assembly for all who labour." (4)

At the Tenth Party Congress in 1922, Lenin proposed a resolution that would ban all factions within the party. He argued that factions within the party were "harmful" and encouraged rebellions such as the Kronstadt Rising. The Party Congress agreed with Lenin and the Workers' Opposition was dissolved. (5) Koltsov and his brother, Boris Efimov, remained reformers and were members of what became known as the Left Opposition. (6)

Mikhail Koltsov - Journalist

After the death of Lenin, Koltsov became a close associate of Joseph Stalin and was described as "the confidant and mouthpiece and direct agent of Stalin". It has been claimed that with the help of Stalin he became one of the most important journalists in the Soviet Union. (7) It has been argued that "if Pravda featured a readable piece in the 1930s, Koltsov was probably the author". Although he was always willing to give his support to Stalin he was seen as unreliable as "in his writing he could be bitingly satirical". (8)

Koltsov was also close to Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD. It has been claimed that he "certainly cultivated the sexually degenerate Yezhov". (9) Koltsov described Yezhov in one newspaper article as "a wonderful unyielding Bolshevik who, without getting up from his desk day and night is unravelling and cutting the threads of fascist conspiracy." (10)

Mikhail Koltsov married a fellow journalist, Elisabeta Ratmanova, who also worked for the NKVD. However, he also had a relationship with Maria Osten. She was "green-eyed with a sensual, almond-shaped face" and Koltsov had been in love with her ever since the writer Ludwig Renn had introduced them in Berlin in 1932. (11)

In 1933 Mikhail Koltsov published a book where he attempted to justify the methods used by Stalin to deal with counter-revolutionaries. "To do this work we need really honest, really unselfish, really reliable communist revolutionaries. We have them, and those whom the Party and the Soviet State have appointed to other posts must never forget the services rendered by these men... Over the champagne glasses, mercenaries and spies, assassins and frauds, provocateurs and gamblers are being given their instructions - to destroy the Soviet rule." (12)

In June 1935 Koltsov organized a Congress of Writers in support of "Culture against Fascism" in Paris. A group of French intellectuals told Koltsov they would boycott the meeting if he did not arrange for dissident Soviet writers such as Isaac Babel and Boris Pasternak, to attend. Stalin agreed to this but was furious when writers such as Andre Malraux, Andre Gide and Gaetano Salvemini, made speeches that were critical of the government in the Soviet Union. Overall, the participants failed to "praise Stalin as loudly as they condemned Hitler". (13)

One of the delegates, Magdalene Paz, raised the case of Victor Serge, a writer who had been arrested and accused of being a supporter of Leon Trotsky. Gide and Salvemini, both supported Paz in complaining about this injustice. The Soviet delegates attempted to defend Stalin and accused Serge as being involved in the assassination of Sergy Kirov, which had taken place two years after his arrest. Stalin released Serge a few months later. This is probably the only occasion on which foreign opinion was able to influence Stalin. However, it has been claimed that Stalin never forgave Koltsov for this diplomatic disaster. (14)

Martha Gellhorn, an American journalist, got to know him during this period. "He was a small thin man, with thick, well-cut, grey hair. He wore a dark, excellent suit. He had the kind of face that makes an immediate impression of brilliance, of wit, and the quiet manners of complete confidence. I thought he was... more French than Russian." (15)

Spanish Civil War

In 1936 he was sent to cover the Spanish Civil War. It was reported that in January 1937, Koltsov, commanded a section of Russian tanks in the battles of Pozuelo de Alarcón and Aravaca. Although some historians have considered this an exaggeration, he did send a "steady stream of long and vividly written articles back to Russia". (16)

Roman Karmen, a photo-journalist, covering the war, commented that he was amazed at Koltsov's ability "to write forty lines with astonishing speed, real wit and careful and thoughtful observation to give a perfectly finished portrait of the political situation". Karmen later wrote that "our friendship constituted a priceless education in militant journalism" and that he was "an acute chronicler of extraordinary events, a political being, an intrepid soldier." (17)

While in Spain he met Ernest Hemingway. The two men became close friends and Koltsov was the model for the character Karkov in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. (18) Hemingway described him as "the most intelligent man he had ever met... with a spitting way of talking through his bad teeth, he looked comic.... but he had more brains and more inner dignity and outer insolence and humour than anybody he had ever known". (19)

Claud Cockburn, a British journalist, was also impressed with Koltsov: "I spent a great deal of my time in the company of Mikhail Koltsov, who then was Foreign Editor of Pravda... He was a stocky little Jew from Odessa - with a huge head and one of the most expressive faces of any man I ever met. What his face principally expressed was a kind of enthusiastically gleeful amusement - and a lively hope that you and everyone else would, however depressing the circumstances, do your best to make things more amusing still. He had a savagely satirical tongue - and an attitude of entire ruthlessness towards people he thought either incompetent or even just pompous. People who did not know him well - particularly non-Russians - thought his conversation, his sharply pointed Jewish jokes, his derisive comments on all kinds of Sacred Cows, unbearably cynical." (20)

Paulina Abramson, who worked as his interpreter, argues that not everyone got on with Koltsov. "Many people who had the good fortune to know Koltsov were attracted by his temperament and by his ability to capture instantly the essence of any problem. I don't dare say that he was liked by everyone who knew him; indeed there were those who seriously disliked him. He was an intolerant person, to some extent, and just could not put up with limited or obtuse people." (21) Ilya Ehrenburg, another Soviet journalist who was reporting on the Spanish Civil War, commented that "the friendship which he professed towards me was tainted by a touch of contempt." (22)

Mikhail Koltsov developed a reputation for being a womanizer. Sefton Delmer recorded that he always turned up on the front-line "with one or more of his train of women. He would have with him either his wife, a neurotic-looking ex-ballerina, or Comrade Bola, an enormous cheerful peasant who was his secretary assistant, or Maria Osten, a blond vivacious gamine of a young German Communist." (23)

On his return to Moscow in May 1937, Koltsov had a three-hour private meeting with Stalin where he told him about recent developments in Spain. As Koltsov was leaving Stalin called him back and a strange conversation followed. Stalin asked him if he had a revolver. When he replied yes, he asked him if he intended to commit suicide. Koltsov took this as a warning. (24)

Show Trials

On his return to the Soviet Union he wrote a series of articles for Isvestia on the Show Trials and accused people such as Alexei Rykov, Victor Chernov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov and Leon Trotsky of being traitors of the revolution. He wrote to his friend, Lion Feuchtwanger, about how he had sat for a week in the courtroom, and was "rendered speechless by the mountains of filth and crime" he had heard. (25)

On 8th July, 1937, Koltsov made a speech where he argued: "There are some people who are wondering why we, the Soviet writers, support the vigorous and pitiless measures of our government against traitors, spies and enemies of the people. These people ask how, despite being good Soviet patriots, as well as workers with peace-loving and defensive pens, can we leave all this to the immovable instruments of state and keep our distance from it; why we do not interfere and simply keep quiet about it, not drawing attention to it in the pages of our publications. No, colleagues and comrades, for us this is a matter of honour. The honour of the Soviet writer consists precisely in being at the forefront in the battle against treachery, against any attack on the liberty and independence of our people. We support our government and justify its actions not only because they are just but because our government will lead us to abundance and happiness. We support it because it is strong, its hand does not shake when punishing the enemy. " (26)

Alexei Rykov, Victor Chernov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov and Leon Trotsky.

Mikhail Koltsov's brother, Boris Efimov, pointed out that during this period he remained close to Stalin. "He (Mikhail Koltsov) believed deeply, honestly - and I am not afraid to say this - almost fanatically in Stalin's wisdom. My brother often told me in detail of his encounters with Stalin, of his mannerisms in conversation, his remarks, turns of phrase and his jokes. He loved everything about Stalin."

Koltsov gradually began to have doubts about Stalin's behaviour: "I think and I think but I can't understand anything. What is going on? How did it turn out that we suddenly have so many enemies? These are people that we've known for years, that we lived with cheek-by-jowl for years! Army commanders, Civil War heroes, party veterans! And for some reason, no sooner have they disappeared behind bars than they immediately confess that they are enemies of the people, spies, agents of foreign intelligence services. What's going on? I think I'm going out of my mind." (27)

Arrest & Execution

On 19th December, 1937, Mikhail Koltsov published an article criticizing some aspects of the purges. Koltsov claimed that to protect themselves, some people had smeared the innocent and called on the party, the government, the courts and public opinion to put a stop to such "heartless liars who violated the rights of Soviet citizens". (28)

Koltsov told his brother that he was in danger as his name had been put on a death list produced by Nikolai Yezhov. Like others he was "still at liberty and at work, who had in fact already been condemned and annihilated by one stroke of this red pencil... Yezhov was left with merely the technical details - working up the cases and producing the orders for arrest." (29)

In September 1938, Koltsov was sent to Prague to report on the negotiations between Adolf Hitler and Neville Chamberlain. Koltsov had a meeting with his old friend Claud Cockburn. He told Cockburn that he was in danger of being arrested: "Koltsov... entertained me at lunch with a kind of fantastic burlesque based on the imaginary future trial of himself for counter-revolutionary activities, taking in turn the part of a grimly furious Public Prosecutor and of himself in the role of a clown who had been caught out and still cannot resist making fatal jokes." (30)

Koltsov had been sent to Prague to negotiate with the Czech government. He told Cockburn that he had been authorized to inform President Eduard Benes that the Soviet Union was ready to send troops, artillery and aircraft when hostilities began. He still hoped that the Soviet Union, Britain and France could unite on behalf of Czechoslovakia against Nazi Germany. Another journalist friend, Louis Fischer, reported that Koltsov was plunged into despair when this failed to happen. (31)

Koltsov hoped to make a trip to Paris to see Maria Osten but at the last minute, the Soviet Ambassador told him that he had received orders for his immediate return to Moscow. According to Paul Preston "he must have known that the end of his hopes for a continuation of the anti-fascist struggle went hand in hand with his own destruction". (32)

Koltsov was arrested on 12th December, 1938. Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) claims that the main reason was that Stalin was determined to arrest all of his representatives that had spent time in Spain during the civil war. For example, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, who had been the Soviet Ambassador to Madrid, was arrested at the same time. (33)

Donald Rayfield, the author of Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) puts forward another theory. When the secret police arrested Mikhail Prezent, a journalist friend of Koltsov, they discovered his diary. It showed that Prezent was a supporter of Leon Trotsky, who was described as the "last intelligent man in politics". Prezent's diary also implied that Koltsov was a supporter of Trotsky. It also included comments by Koltsov about Stalin's uncouth habits. (34)

Other historians, such as Marc Jansen, believes his affair with Yevgenia Feinberg, the wife of Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, was an important factor in his arrest. It is believed that Yezhov added Koltsov's name to the 346 "enemies of the people" marked for execution. (35) Another historian has discovered information that Andre Marty, who served with Koltsov in Spain, contacted Stalin and accused him of being a "Trotskyist". (36)

Koltsov was accused of being the leader of a network of spies that included Walter Krivitsky, Alexander Orlov, Ilya Ehrenburg, Isaac Babel, Boris Pasternak, Maria Osten, Andre Malraux, Maxim Litvinov, Evgeni Gnedin and Vsevolod Meyerhold. Koltsov was tortured by Lavrenty Beria and according to Alexander Fadeyev he eventually admitted to working with the French and German intelligence agencies. (37)

Mikhail Koltsov was tried before Vasiliy Ulrikh on 1st February, 1940. He retracted all his confessions but was found guilty and shot that night.

Primary Sources

(1) Martha Gellhorn, London Review of Books (12th December 1996)

Mikhail Koltsov... was a small thin man, with thick, well-cut, grey hair. He wore a dark, excellent suit. He had the kind of face that makes an immediate impression of brilliance, of wit, and the quiet manners of complete confidence. I thought he was forty or so, and more French than Russian.

(2) Claud Cockburn, A Discord of Trumpets (1956) page 304

I spent a great deal of my time in the company of Mikhail Koltsov, who then was Foreign Editor of Pravda and, more importantly still, was at that period... the confidant and mouthpiece and direct agent of Stalin himself. He was a stocky little Jew from Odessa, I think - with a huge head and one of the most expressive faces of any man I ever met. What his face principally expressed was a kind of enthusiastically gleeful amusement - and a lively hope that you and everyone else would, however depressing the circumstances, do your best to make things more amusing still.

He had a savagely satirical tongue - and an attitude of entire ruthlessness towards people he thought either incompetent or even just pompous. People who did not know him well - particularly non-Russians - thought his conversation, his sharply pointed Jewish jokes, his derisive comments on all kinds of Sacred Cows, unbearably cynical. And others, who had known them both, said that he reminded them of Karl Radek (an ominous comparison).

To myself it never seemed that anyone who had such a powerful enthusiasm for life - for the humour of life, for all manifestations of vigorous life from a tank battle to Elizabethan literature to a good circus - could possibly be described properly as "cynical". Realistic is perhaps the word - but that is not quite correct either, because it implies, or might imply, a dry practicality which was quite lacking from his nature. At any rate so far as his personal life and fate were concerned he unquestionably and positively enjoyed the sense of danger, and sometimes - by his political indiscretions, for instance, or his still more wildly indiscreet love affairs - deliberately created dangers which need not have existed.

(3) Paulina Abramson, Mosaico Roto (1994) page 62

Many people who had the good fortune to know Koltsov were attracted by his temperament and by his ability to capture instantly the essence of any problem. I don't dare say that he was liked by everyone who knew him; indeed there were those who seriously disliked him. He was an intolerant person, to some extent, and just could not put up with limited or obtuse.

(4) Mikhail Koltsov, speech (8th July, 1937)

There are some people who are wondering why we, the Soviet writers, support the vigorous and pitiless measures of our government against traitors, spies and enemies of the people. These people ask how, despite being good Soviet patriots, as well as workers with peace-loving and defensive pens, can we leave all this to the immovable instruments of state and keep our distance from it; why we do not interfere and simply keep quiet about it, not drawing attention to it in the pages of our publications. No, colleagues and comrades, for us this is a matter of honour. The honour of the Soviet writer consists precisely in being at the forefront in the battle against treachery, against any attack on the liberty and independence of our people. We support our government and justify its actions not only because they are just but because our government will lead us to abundance and happiness. We support it because it is strong, its hand does not shake when punishing the enemy.

Student Activities

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 179

(2) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(3) Cathy Porter, Alexandra Kollontai: A Biography (1980) pages 326-27

(4) Workers' Opposition, statement (27th February, 1921)

(5) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949) page 227

(6) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 193

(7) Claud Cockburn, A Discord of Trumpets (1956) page 304

(8) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) page 251

(9) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 193

(10) Dmitri Volkogonov, Stalin, Triumph and Tragedy (1991) page 330

(11) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 187

(12) Mikhail Koltsov, The Man in Uniform (1933) pages 43-45

(13) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) page 352

(14) Robert Conquest, The Great Terror (1990) page 464

(15) Martha Gellhorn, London Review of Books (12th December 1996)

(16) Jonathan Haslam, The Soviet Union and the Struggle for Collective Security in Europe (1984) page 262

(17) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 184

(18) Roman Karmen, No Pasaran! (1976) pages 272-278

(19) Douglas Martin, New York Times (4th October, 2008)

(20) Claud Cockburn, A Discord of Trumpets (1956) page 304

(21) Paulina Abramson, Mosaico Roto (1994) page 62

(22) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 187

(23) Sefton Delmer, Trail Sinister (1961) page 387

(24) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) page 360

(25) Mikhail Koltsov, letter to Lion Feuchtwanger (11th March, 1938)

(26) Mikhail Koltsov, speech (8th July, 1937)

(27) Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) page 402

(28) Mikhail Koltsov, Pravda (19th December, 1937)

(29) Robert Conquest, The Great Terror (1990) page 63

(30) Claud Cockburn, A Discord of Trumpets (1956) pages 311-312

(31) Louis Fischer, Men and Politics (1941) page 524

(32) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 203

(33) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 239

(34) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) page 251

(35) Marc Jansen, Stalin's Loyal Executioner (2002) page 185

(36) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 205

(37) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) pages 352-353