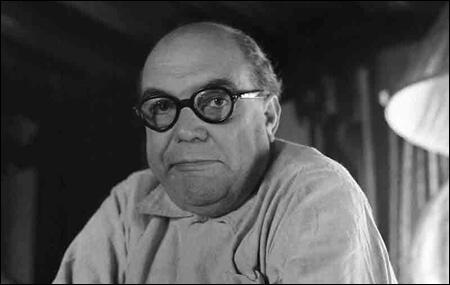

Sefton Delmer

Denis Sefton Delmer was born in Berlin, Germany, on 24th May 1904. His father, Frederick Delmer, was an Australian lecturer in English at Berlin University and on the outbreak of the First World War was interned as an enemy alien. In 1917 Delmer and his family were allowed to go to England.

Delmer was educated at Lincoln College, Oxford, where he obtained a second class degree in German. After leaving university he worked as a freelance journalist until being recruited by the Daily Express to become head of its new Berlin Bureau. While in Germany he became friendly with Ernst Roehm and he arranged for him to become the first British journalist to interview Adolf Hitler. In the 1932 general election Delmer travelled with Hitler on his private aircraft. He was also with Hitler when he inspected the Reichstag Fire. During this period Delmer was criticized for being a Nazi sympathizer and for a time the British government thought he was in the pay of the Nazi regime.

In 1933 Delmer was sent to France as head of the Daily Express Paris Bureau. He also covered important stories in Europe including the Spanish Civil War and the invasion of Poland by the German Army in 1939. He also reported on the German Western Offensive in 1940.

Delmer returned to England and in September 1940 he was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to organize 'Black Propaganda' broadcasts to Nazi Germany. This included Soldatensender Calais, a pseudo-German radio station established in Crowborough for the German armed forces. Delmer's propaganda stories included spreading rumours that foreign workers were sleeping with the wives of German soldiers serving overseas. When Stafford Cripps discovered what Delmer was up to he wrote to Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary: "If this is the sort of thing that is needed to win the war, why, I'd rather lose it."

After the Second World War Delmer became chief foreign affairs reporter for the Daily Express. Over the next fifteen years Delmer covered nearly every major foreign news story for the newspaper. However, rumours began to circulate that Delmer was spying for the Soviet Union.

Lord Beaverbrook sacked Delmer in 1959 and he retired to Suffolk where he wrote two volumes of autobiography, Trial Sinister (1961), Black Boomerang (1962) and several other books including Weimar Germany (1972) and The Counterfeit Spy (1973).

Sefton Delmer died at Lamarsh, Suffolk, on 4th September 1979.

Primary Sources

(1) D. Sefton Delmer, Daily Express (23rd February, 1933)

The arson of the German parliament building was allegedly the work of a Communist-sympathizing Dutchman, van der Lubbe. More probably, the fire was started by the Nazis, who used the incident as a pretext to outlaw political opposition and impose dictatorship.

"This is a God-given signal! If this fire, as I believe, turns out to be the handiwork of Communists then there is nothing that shall stop us now crushing out this murder pest with an iron fist."

Adolf Hitler, Fascist Chancellor of Germany, made this dramatic declaration in my presence tonight in the hall of the burning Reichstag building.

The fire broke out at 9.45 tonight in the Assembly Hall of the Reichstag.

It had been laid in five different comers and there is no doubt whatever that it was the handiwork of incendiaries. One of the incendiaries, a man aged thirty, was arrested by the police as he came rushing out of the building, clad only in shoes and trousers, without shirt or coat, despite the icy cold in Berlin tonight.

Five minutes after the fire had broken out I was outside the Reichstag watching the flames licking their way up the great dome into the tower.

A cordon had been flung round the building and no one was allowed to pass it.

After about twenty minutes of fascinated watching I suddenly saw the famous black motor car of Adolf Hitler slide past, followed by another car containing his personal bodyguard.

I rushed after them and was just in time to attach myself to the fringe of Hitler's party as they entered the Reichstag.

Never have I seen Hitler with such a grim and determined expression. His eyes, always a little protuberant, were almost bulging out of his head.

Captain Goring, his right-hand man, who is the Prussian Minister of the Interior, and responsible for all police affairs,

joined us in the lobby. He had a very flushed and excited face.

'This is undoubtedly the work of Communists, Herr Chancellor,' he said.

'A number of Communist deputies were present here in the Reichstag twenty minutes before the fire broke out. We have succeeded in arresting one of the incendiaries.'

'Who is he?' Dr Goebbels, the propaganda chief of the Nazi Party, threw in.

'We do not know yet,' Captain Goring answered, with an ominously determined look around his thin, sensitive mouth. 'But we shall squeeze it out of him, have no doubt, doctor.'

We went into a room. 'Here you can see for yourself, Herr Chancellor, the way they started the fire,' said Captain Goring, pointing out the charred remains of some beautiful oak panelling.

'They hung cloths soaked in petrol over the furniture here and set it alight.'

We strode across another lobby filled with smoke. The police barred the way. 'The candelabra may crash any moment, Herr Chancellor,' said a captain of the police, with his arms outstretched.

By a detour we next reached a part of the building which was actually in flames. Firemen were pouring water into the red mass.

Hitler watched them for a few moments, a savage fury blazing from his pale blue eyes. Then we came upon Herr von Papen, urbane and debonair as ever. Hitler stretched out his hand and uttered the threat against the Communists which I have already quoted. He then turned to Captain Goring. 'Are all the other public buildings safe?' he questioned.

'I have taken every precaution,' answered Captain Goring. 'The police are in the highest state of alarm, and every public building has been specially garrisoned. We arc waiting for anything.'

It was then that Hitler turned to me. 'God grant', he said, 'that this is the work of the Communists. You are witnessing the beginning of a great new epoch in German history. This fire is the beginning.'

And then something touched the rhetorical spring in his brain. 'You see this flaming building,' he said, sweeping his hand dramatically around him. 'If this Communist spirit got hold of Europe for but two months it would be all aflame like this building.'

By 12.30 the fire had been got under control. Two Press rooms were still alight, but there was no danger of the fire spreading. Although the glass of the dome has burst and crashed to the ground the dome still stands.

So far it has not been possible to disentangle the charred debris and see whether the bodies of any incendiaries, who may have been trapped in the building, are among it.

At the Prussian Ministry of the Interior a special meeting was called late tonight by Captain Goring to discuss measures to be taken as a consequence of the fire.

The entire district from the Brandenburg Gate, on the west, to the River Spree, on the east, is isolated tonight by numerous cordons of police.

(2) James Douglas-Hamilton, Motive for a Mission (1971)

Clearly they wished to make contact with certain persons in Britain in order to find out where Hess was confined. It is not known whether they were sent by Himmler, Schellenberg or Heydrich. All that is known is that the British Secret Service picked them up, and drove them to a secret establishment, where they were identified, interrogated and executed. Such were the rules of war: Rudolf Hess had at least arrived in uniform.

Even so his presence in Britain was never explained by the British Government, and as no statement was made he could not be exploited for propaganda purposes. Sefton Delmer, who was working for the Directorate of Psychological Warfare, wrote that he found it frustrating that the psychological warfare agencies and the deception experts were not permitted to use the incident in order to confuse and distress the Germans.,-, However, Churchill was now adamant that no useful purpose could be served by telling the British people that a Nazi leader had made a serious peace initiative and that was the end of the matter. Churchill was quite content to leave the Germans weltering in their own embarrassment.

Sefton Delmer remained dissatisfied; and he was not alone. Dr Kurt Hahn believed that he, too, could see an opportunity in Hess's flight. Hahn was a patriotic German of Jewish origin and had been imprisoned by the Nazis in i933 for his outspoken opposition to Nazism. After the British Premier Ramsay Macdonald interceded on his behalf Hahn was released; and he came to Britain, where he founded Gordonstoun School. During the war he worked for the British Foreign Office translating German news cuttings, and on 2o May 1941 he submitted a report on Hess's flight, suggesting that the Haushofers were behind it. His theme was that Hess's action indicated that `there was a great longing for peace in Germany of which Hess had become the unconscious and silent Ambassador. Now was the moment to encourage the German Resistance and to make it clear to the German people that the British would never make peace with Hitler, but that a cleansed and liberated Germany had nothing to fear from Britain.'

(3) D. Sefton Delmer, Daily Express (23rd October, 1956)

I have been the witness today of one of the great events of history. I have seen the people of Budapest catch the fire lit in Poznan and Warsaw and come out into the streets in open rebellion against their Soviet overlords. I have marched with them and almost wept for joy with them as the Soviet emblems in the Hungarian flags were torn out by the angry and exalted crowds. And the great point about the rebellion is that it looks like being successful.

As I telephone this dispatch I can hear the roar of delirious crowds made up of student girls and boys, of Hungarian soldiers still wearing their Russian-type uniforms, and overalled factory workers marching through Budapest and shouting defiance against Russia. 'Send the Red Army home,' they roar. 'We want free and secret elections.' And then comes the ominous cry which one always seems to hear on these occasions: 'Death to Rakosi.' Death to the former Soviet puppet dictator - now taking a 'cure' on the Russian Black Sea Riviera - whom the crowds blame for all the ills that have befallen their country in eleven years of Soviet puppet rule.

Leaflets demanding the instant withdrawal of the Red Army and the sacking of the present Government are being showered among the street crowds from trams. The leaflets have been printed secretly by students who 'managed to get access', as they put it, to a printing shop when newspapers refused to publish their political programme. On house walls all over the city primitively stencilled sheets have been pasted up listing the sixteen demands of the rebels.

But the fantastic and, to my mind, really super-ingenious feature of this national rising against the Hammer and Sickle, is that it is being carried on under the protective red mantle of pretended Communist orthodoxy. Gigantic portraits of Lenin are being carried at the head of the marchers. The purged ex-Premier Imre Nagy, who only in the last couple of weeks has been readmitted to the Hungarian Communist Party, is the rebels' chosen champion and the leader whom they demand must be given charge of a new free and independent Hungary. Indeed, the Socialism of this ex-Premier and - this is my bet - Premier-soon-to-be-again, is no doubt genuine enough. But the youths in the crowd, to my mind, were in the vast majority as anti-Communist as they were anti-Soviet - that is, if you agree with me that calling for the removal of the Red Army is anti-Soviet.