Boris Efimov

Boris Efimov, the second son of a Jewish shoemaker in Kiev, was born in Russia on 28th September, 1900. When he was eleven years old he saw Tsar Nicholas II. (1)

Drawing was a hobby, and he intended to become a lawyer until he became involved in the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Inspired by the oratory of Leon Trotsky, he became a Bolshevik and from 1920 to 1921, Efimov designed posters and brochures for the communist organ Agitprop. In 1922 he moved to Moscow to live with his brother, Mikhail Koltsov, who helped him get a job as a cartoonist for Pravda. (2) In 1922 he began contributing to Krokodil. (3)

For a time Efimov was a supporter of what became known as the Workers' Opposition. The leaders of this group were Alexandra Kollantai (Commissar for Welfare) and Alexander Shlyapnikov (Commissar for Labour). Kollantai published a pamphlet The Workers' Opposition, where she called for members of the party to be allowed to discuss policy issues and for more political freedom for trade unionists. She also advocated that before the government attempts to "rid Soviet institutions of the bureaucracy that lurks within them, the Party must first rid itself of its own bureaucracy." (4)

At the Tenth Party Congress in 1922, Lenin proposed a resolution that would ban all factions within the party. He argued that factions within the party were "harmful" and encouraged rebellions such as the Kronstadt Rising. The Party Congress agreed with Lenin and the Workers' Opposition was dissolved. (5) Boris Efimov and his brother, Mikhail Koltsov, remained reformers and were members of what became known as the Left Opposition. (6)

After the death of Lenin, Efimov became a close associate of Joseph Stalin. He later admitted that he produced propaganda on behalf of the communist government. "In my opinion, propaganda appeared together with Soviet power, after the October revolt. Before I think people didn't even know the meaning of the word. People knew it existed, but it didn't have such a wide meaning or scope... Sometimes propaganda suggested something correct and fair, and sometimes suggested something completely absurd, inhuman, against nature. But the strength of propaganda always overcame. People started to believe in something." (7)

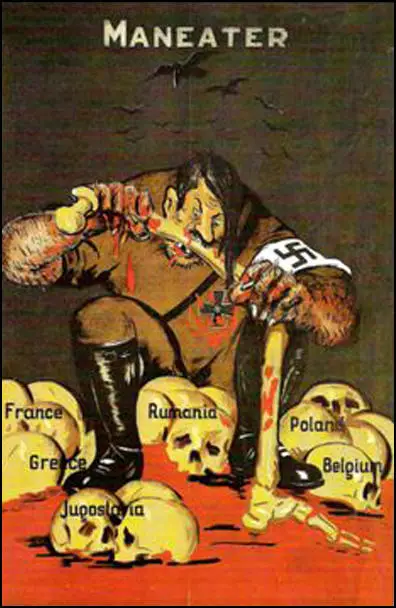

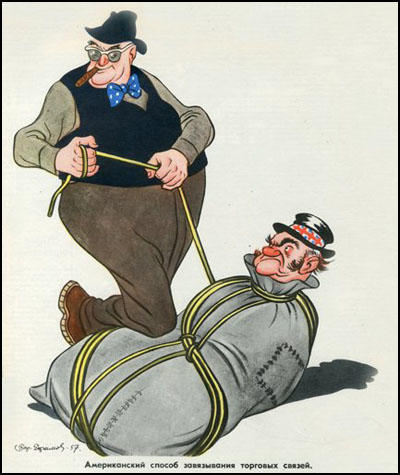

Foreign politicians were often the target of Boris Efimov's wit. "Among those who felt his artistic wrath were bourgeois capitalists, Italian fascists, and anti-Soviet British politicians". In 1927 Austen Chamberlain, the British Foreign Minister, formally complained to Soviet authorities about a cartoon that ridiculed his policies. (8)

Boris Efimov was a good friend of Leon Trotsky. It has been pointed out that when in "1929, Trotsky was to be deported from the Soviet Union, Boris visited him to say goodbye. Although he did this as secretly as possible, Stalin found out and remarkably took no action. For anyone else it would have been a death sentence but Boris's cartoons were obviously a vital propaganda tool to the regime. This would not be the first time, Boris was saved by his talent to draw." (9)

Boris Efimov & Joseph Stalin

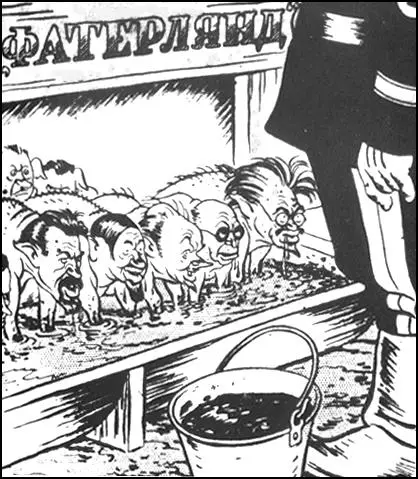

Boris Efimov also worked for Isvestia. In 1937 he covered the Show Trials and accused people such as Nikolay Bukharin and Leon Trotsky of being traitors of the revolution. During this period Efimov compliantly drew vicious political cartoons against those he had previously so admired within the Soviet leadership. Kevin McNeer points out that "his drawings during the infamous Show Trials of the 30s, when Efimov published vicious political cartoons against his friends, including Bukharin and Trotsky, depicting them as Nazis and spies when he knew the accusations against them were false." (10)

Alexei Rykov, Victor Chernov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov and Leon Trotsky.

Efimov justified his work as his role in convincing people of the merits of communism: "The question of whether people believed in something positive, despite these terrible hideous atrocities that were going on in the country, I would say that they wanted to believe. Because to not believe, you know, is already the end of a person. A person has to believe in something, has to have some kind of hope, or it is already the end of him. So they wanted to believe that this was happening by chance, only now and again, that everything would be all right." (11)

Efimov remained loyal to Joseph Stalin and portrayed his rivals as "enemies of the people". (12) Efimov later defended his actions during this period. "What was I supposed to say when I heard with my own ears how he confessed that he was a traitor, a turncoat, an enemy of Soviet power? It was a complicated time. Now it’s fine to criticize. I am not Giordano Bruno to burn at the stake on a matter of principle. I knew that if I said, ‘No, I won’t!’ I would end up in the very same place. My family, my wife would be killed. I recall those cartoons with aggravation, with shame, with disappointment, but I couldn’t have acted differently then." (13)

Mikhail Koltsov

Efimov’s brother, Mikhail Koltsov, remained close to Stalin. "He (Mikhail Koltsov) believed deeply, honestly - and I am not afraid to say this - almost fanatically in Stalin's wisdom. My brother often told me in detail of his encounters with Stalin, of his mannerisms in conversation, his remarks, turns of phrase and his jokes. He loved everything about Stalin."

Koltsov gradually began to have doubts about Stalin's behaviour: "I think and I think but I can't understand anything. What is going on? How did it turn out that we suddenly have so many enemies? These are people that we've known for years, that we lived with cheek-by-jowl for years! Army commanders, Civil War heroes, party veterans! And for some reason, no sooner have they disappeared behind bars than they immediately confess that they are enemies of the people, spies, agents of foreign intelligence services. What's going on? I think I'm going out of my mind." (14)

On 19th December, 1937, Mikhail Koltsov published an article criticizing some aspects of the purges. Koltsov claimed that to protect themselves, some people had smeared the innocent and called on the party, the government, the courts and public opinion to put a stop to such "heartless liars who violated the rights of Soviet citizens". (15)

Koltsov told his brother that he was in danger as his name had been put on a death list produced by Nikolai Yezhov. Like others he was "still at liberty and at work, who had in fact already been condemned and annihilated by one stroke of this red pencil... Yezhov was left with merely the technical details - working up the cases and producing the orders for arrest." (16)

Mikhail Koltsov was arrested on 12th December, 1938. Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) claims that the main reason was that Stalin was determined to arrest all of his representatives that had spent time in Spain during the civil war. For example, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, who had been the Soviet Ambassador to Madrid, was arrested at the same time. (17)

Donald Rayfield, the author of Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) puts forward another theory. When the secret police arrested Mikhail Prezent, a journalist friend of Koltsov, they discovered his diary. It showed that Prezent was a supporter of Leon Trotsky, who was described as the "last intelligent man in politics". Prezent's diary also implied that Koltsov was a supporter of Trotsky. It also included comments by Koltsov about Stalin's uncouth habits. (18)

Other historians, such as Marc Jansen, believes his affair with Yevgenia Feinberg, the wife of Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, was an important factor in his arrest. It is believed that Yezhov added Koltsov's name to the 346 "enemies of the people" marked for execution. (19) Another historian has discovered information that Andre Marty, who served with Koltsov in Spain, contacted Stalin and accused him of being a "Trotskyist". (20)

Koltsov was accused of being the leader of a network of spies that included Walter Krivitsky, Alexander Orlov, Ilya Ehrenburg, Isaac Babel, Boris Pasternak, Maria Osten, Andre Malraux, Maxim Litvinov, Evgeni Gnedin and Vsevolod Meyerhold. Koltsov was tortured by Lavrenty Beria and according to Alexander Fadeyev he eventually admitted to working with the French and German intelligence agencies. Koltsov was tried before Vasiliy Ulrikh on 1st February, 1940. He retracted all his confessions but was found guilty and shot that night. (21)

Second World War

Boris Efimov also expected to be arrested and executed: "I prepared myself for my own arrest, since I was as guilty as he. But it never happened. I was left in freedom; I was left alive, and I continued to work. Not straight away, for roughly a year and a half, I was unemployed. They threw me out of the newspapers and magazines where I worked, because I was already known as the brother of an enemy of the people. But then something strange and inexplicable happened. At the same time that my brother's case ended, and he was executed, I was asked to go back to work. It was some gruesome kind of reckoning I don't know what. I could have refused... I did not have the right to do that, because you can direct your own fate, your freedom, your own life, but I had my parents, our parents. I had a wife; I had a young son. If I had done that, they would all have died. So I went back to work." (22)

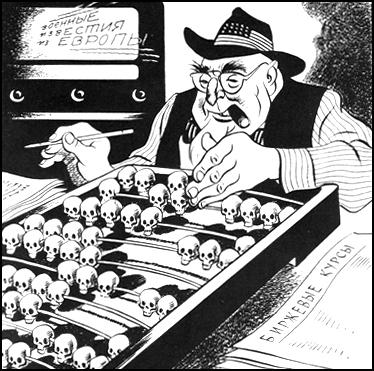

At the time Efimov was expected to produce work in favour of the Nazi-Soviet Pact and to express hostility towards Britain and the United States. In 1940 he produced Blood and Business. "Drawn at a time when the Nazi-Soviet Pact was still very much in force. Using a skull abacus, Uncle Sam keeps a tally of his war profits as the news from Europe is announced on the radio." (23)

On 21st June, 1941, Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa. The country was now at war with Nazi Germany. The first few months of the war was disastrous for the Soviet Union. The German northern forces surrounded Leningrad while the centre group made steady progress towards Moscow. German forces had also made deep inroads into the Ukraine.

In his diary, Joseph Goebbels, wrote: "The Führer thinks that the action will take only 4 months; I think - even less. Bolshevism will collapse as a house of cards. We are facing an unprecedented victorious campaign. Cooperation with Russia was in fact a stain on our reputation. Now it is going to be washed out. The very thing we were struggling against for our whole lives, will now be destroyed. I tell this to the Führer and he agrees with me completely." (24)

Joseph Stalin ordered the Soviet people to fight the advancing German troops: "The Red Army, the Red Navy, and all citizens of the Soviet Union must defend every inch of Soviet soil, must fight to the last drop of blood for our towns and villages, must display the daring, initiative and mental alertness characteristic of our people. In case of forced retreat of Red Army units, all rolling stock must be evacuated, the enemy must not be left a single engine, a single railway truck, not a single pound of grain or gallon of fuel. Collective farmers must drive off all their cattle and turn over their grain to the safe keeping of the state authorities, for transportation to the rear. lf valuable property that cannot be withdrawn, must be destroyed without fail. In areas occupied by the enemy, partisan units, mounted and on foot, must be formed; sabotage groups must be organized to combat enemy units, to foment partisan warfare everywhere, blow up bridges and roads, damage telephone and telegraph lines, set fire to forests, stores and transport. In occupied regions conditions must be made unbearable for the enemy and all his accomplices. They must be hounded and annihilated at every step, and all their measures frustrated." (25)

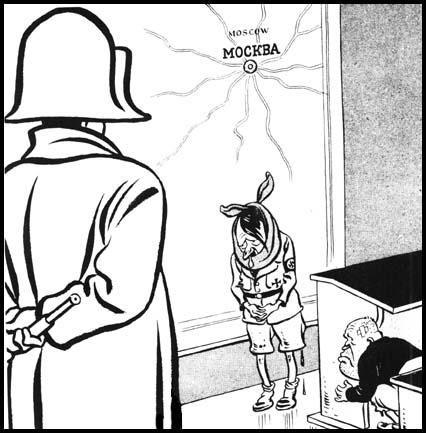

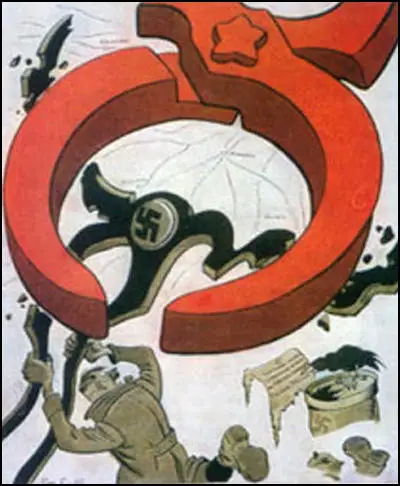

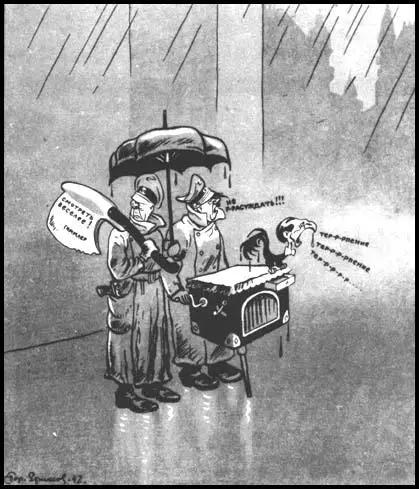

Boris Efimov's contribution to the defence of the Soviet Union was to produce a series of anti-Hitler cartoons. This included The History Lesson (1941). As Mark Bryant, the author of World War II in Cartoons (1982) pointed out: "Boris Efimov... has the cold and snivelling schoolboy Hitler overshadowed by schoolmaster Napoleon (who was in reality a very small man), while Mussolini, whose scars bear witness to an earlier 'history lesson,' cowers in fear." (26) Hitler was upset by this and other cartoons and gave orders for Efimov to be executed when his troops captured Moscow. (27)

Boris Efimov joined 200 artists producing anti-Nazi posters. "These designs, rapidly produced by the stencil method, also acted as wall newspapers, announcing political and military successes. They could be as large as 10 feet high and half as broad, using fifteen to twenty different stencil colours... They were displayed in the windows of the Tass press agency offices throughout the country. They were also distributed to every factory, farm, institute, hospital, army unit, and naval vessel, so that no Soviet citizen went untouched by them." (28)

One of Efimov's most popular cartoons was Whose pincers pinch the most? Joseph Darracott points out the educational aspects of his work: "Boris Efimov uses a map on which are marked the surrounding towns of Mozhaisk, Kaluga, Tulas and Ryazan... This mixture of explanatory diagram and a provocative slogan was a feature of early posters and cartoons for political purposes." (29)

Isobel Montgomery has argued that Boris Efimov was the Soviet's most effective propagandist. "It was Efimov's brutal depictions of a battered German army, held back at the gates of Moscow, and a shrunken, cowering Hitler, for which he will probably be best remembered. In one cartoon, published in 1941, wounded soldiers carry a coffin, inscribed Myth of the Invincibility of the German Army, through the snow as they retreat. Another shows a shrunken Hitler reduced to playing a barrel organ on the street. Cartoons urging German soldiers to surrender were also dropped behind enemy lines." (30)

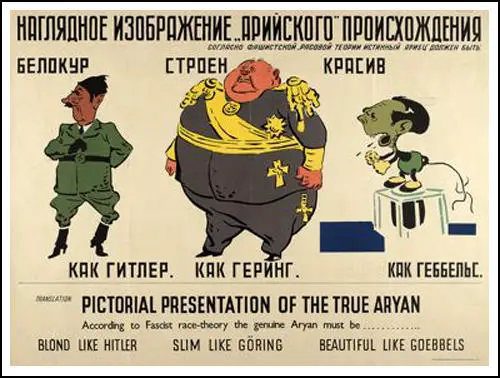

It has been claimed by some critics that Efimov was not as skilled a draughtsman or portrait artist as some of his contemporaries, but had an abundance of wit and was exceptionally well read. One poster, on the Nazi leaders, was considered to be so effective it was also published in English. The cartoonist, Vladimir Mochalov, commented: "Boris Efimov published a famous cartoon with the caption: ‘A True Aryan is Tall’, and he drew a small, scrawny Goebbels; ‘A True Aryan is Fit’, and he drew a fat Goering; and, ‘A True Aryan is Blond’, for which he drew Hitler with his black bangs. This was an absolutely timely, witty drawing, a classic political cartoon that you might call: aiming straight between the eyes." (31)

David Low, Britain most famous war cartoonist, published several drawings on the plight of the Soviet Union. He called on the British government to provide more military help to the latest recruit in the fight against Nazi Germany. In August, 1942, Low called for an opening of a second front in Europe. (32) Boris Efimov thanked Low for his efforts: "I wish to tell you, Mr. Low, with interest I and other Soviet artists have been and are now following your magnificent work, which has won for you the well-deserved fame of the best cartoonist in the world. The future of history hangs in the balance. On one hand light, progress, democracy, life; on the other darkness, corruption, barbarism, death, that is Hitlerism. I am happy, dear Mr. Low, that in this decisive hour I am with you - a great artist whose creative work I regard with admiration and from whose works I learn." (33)

Low visited Efimov in Moscow and discovered that he was paid 6,000 roubles a month, four times the official salary of Joseph Stalin. (34) Low later recalled: "It is obvious from a study of his cartoons that he thinks, quite rightly, that Hitler is a fool. His Goebbels is a rat. His Himmler is a neat sneak. His Goering is a fat slob." (35)

Efimov believed his work was very important in keeping morale high. "Cartoons are the first thing that a reader of a newspaper looks at. He takes it in more quickly and more completely than any long article you would read. A cartoon instantaneously gives you both the event and the commentary about that event. That is the nature of a cartoon: fast, funny and persuasive." (36)

The Cold War

After the war Joseph Stalin used Boris Efimov as a weapon in the Cold War. He later recalled in an interview with PBS: "When the war finished, and our allies stopped being our allies, there was created a situation where we started to depict them as a kind of enemy, as aggressors.... But that was the politics of the Soviet Union at the time. The same was true of the politics of the West. We portrayed Churchill and Truman as aggressors and warmongers, and the West portrayed Stalin and Molotov as aggressors and warmongers as well.... If you need an example here is one: I was often impressed by Churchill, by his will, by his wonderful oratory talent, his jokes. I really liked him. And then it was announced that he was our enemy, and we had to draw cartoons about him, and when I drew him looking in the mirror and seeing a reflection of Hitler, that was, for me, not convincing and not pleasant. I realized that Hitler was a real Fascist enemy, and that Churchill was a big government figure. I understood that this was not true, and I didn't believe it in my heart, in my soul, but that was government policy, and it was a situation against which I could not act." (37)

After the death of Joseph Stalin, Efimov remained a supporter of his sponser: "He gave me my life and my work – how can I not be grateful for that?... He could have lifted his little finger, and we wouldn’t be having this conversation today.” (38)

As Tim Benson has pointed out: "By the 1960's, Boris personified Israel as a blood thirsty fascist client state of American imperialism. During the 1967 and 1973 wars, Efimov personified Israel as a burly, gun-toting aggressor. In some cartoons, the Star of David merges with a skull and crossbones and although he steered clear of Jewish physical stereotypes he did use Nazi imagery to associate it with Israel's actions. During the Six Day war, Boris even signed an official letter condemning Israel for its aggression towards the Arab states surrounding it. Boris later argued that his own anti-Israel cartoons needed to be seen as part of an international political context, and he viewed them as understandable at the time but was later ashamed of them." (39)

Boris Efimov was still alive when communism collapsed in the Soviet Union. He disliked the changes that followed: "Propaganda was born together with the Soviet regime in 1917, and through all 70 years of its existence, propaganda helped to consolidate society, held it in some kind of unified, strong community. And when the Soviet Union disappeared and propaganda disappeared with it, there was left a sort of emptiness." (40)

In 2005 Efimov gave an interview to the American film director, Kevin McNeer and asked him about his relationship with Stalin: "Boris and I would go back and forth about this as we filmed, and after one such session, he suddenly realized how bizarre what he was saying must have sounded to me. It was a striking moment of self awareness – he saw himself from my perspective, the perspective of a young American who couldn’t fathom what life in the Soviet Union in the 30s was like." (41)

Efimov continued to produce cartoons into his last years. On his 107th birthday he was given the title of chief cartoonist of Isvestia in recognition of 80 years work for the paper. (42) Later that year several Israeli newspapers reported that he was very likely the oldest living Jew. (43)

Boris Efimov, died, aged 108, on 1st October, 2008.

Primary Sources

(1) Zbyněk Zeman, Heckling Hitler (1987)

Low's pre-war cartoons advocating cooperation with the Soviet Union did more than merely reflect his left-wing inclinations. Low had visited the Soviet Union, and there he found out that the cartoonist Boris Efimov of Izvestia and his colleague on Pravda were paid 6,000 roubles a month, four times the official salary of Stalin. He also learned that they kept criticism of Stalin's regime to themselves. (page 100)

(2) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

When the war finished, and our allies stopped being our allies, there was created a situation where we started to depict them as a kind of enemy, as aggressors. During the war I was already caricaturing the Americans with dollar signs. It was, of course, still something both unclear and also unpleasant. But that was the politics of the Soviet Union at the time. The same was true of the politics of the West. We portrayed Churchill and Truman as aggressors and warmongers, and the West portrayed Stalin and Molotov as aggressors and warmongers as well.

Cartoons are the first thing that a reader of a newspaper looks at. He takes it in more quickly and more completely than any long article you would read. A cartoon instantaneously gives you both the event and the commentary about that event. That is the nature of a cartoon: fast, funny and persuasive.

If you need an example here is one: I was often impressed by Churchill, by his will, by his wonderful oratory talent, his jokes. I really liked him. And then it was announced that he was our enemy, and we had to draw cartoons about him, and when I drew him looking in the mirror and seeing a reflection of Hitler, that was, for me, not convincing and not pleasant. I realized that Hitler was a real Fascist enemy, and that Churchill was a big government figure.

I understood that this was not true, and I didn't believe it in my heart, in my soul, but that was government policy, and it was a situation against which I could not act.

I want to say that I was convinced that the thoughts and feelings that I put into my cartoons were the thoughts and feelings of millions of people. But we were simple people; we didn't do politics. Those who sat at the very top did the politics. We were the executives, and it was sometimes the case that I had to do something that went against my convictions, but I thought first of all that those at the top knew better about politics. Later I knew that whatever my objections might have been they would have brushed me away like some kind of pawn.

The question of whether people believed in something positive, despite these terrible hideous atrocities that were going on in the country, I would say that they wanted to believe. Because to not believe, you know, is already the end of a person. A person has to believe in something, has to have some kind of hope, or it is already the end of him. So they wanted to believe that this was happening by chance, only now and again, that everything would be all right. And then people living in this country, you know the English expression, "Right or wrong, my country". Right? Where were people meant to go?

It was their country where they lived, and not everyone had somewhere else to run to. All, the majority, millions, had to stay in the country and live under the conditions which existed in that country. People had to believe, and they had to live.

Propaganda was certainly huge, broad, and I would say skillful, talented. Propaganda used music, and poetry and songs and paintings and cartoons. All this was managed by a system, which went from the top down to the bottom, which made people first of all somehow forget, although everything defended all these atrocities, which they committed. At the same time it somehow hypnotized people, that these things were only occasional, that they were necessary, that there in the West it was a lot worse, that here in the Soviet Union it was good. And they told us about the wisdom of Stalin, his kindness and that we shouldn't despair. And people had no way out but to believe. What alternative did they have? Not believing? That would lead to certain death. You had to live under the conditions that existed all over the country. That's what propaganda is.

In my opinion, propaganda appeared together with Soviet power, after the October revolt. Before I think people didn't even know the meaning of the word. People knew it existed, but it didn't have such a wide meaning or scope. All of the 70 years of Soviet power, all were based on propaganda. Sometimes propaganda suggested something correct and fair, and sometimes suggested something completely absurd, inhuman, against nature. But the strength of propaganda always overcame. People started to believe in something.

So today, when there is no propaganda in the sense that there was then, people don't know what to believe in, who to believe. If you sit in front of the television, and one politician appears, and talks about various things, and you believe him. And then another politician appears and you also believe him. Because there are not the same stable propagandistic truths. They are not there. And that is why, I think, the role of religion is so important today. That at least is some kind of stronghold for people to hang on to. Something that people organize themselves with, that they need to believe in God, that is also a kind of propaganda.

The role and meaning of propaganda are very great, very great. Propaganda was born together with the Soviet regime in 1917, and through all 70 years of its existence propaganda helped to consolidate society, held it in some kind of unified, strong community. And when the Soviet Union disappeared and propaganda disappeared with it, there was left a sort of emptiness. Because where, on the one hand, there used to exist one united strong propaganda of the Soviet regime, there now exists several propagandas. Every group, every party has their own propaganda. All this is confusing. It creates some kind of instability. People are disappointed. They don't know who to believe. Now the absence of any kind of unified propaganda is a great misfortune for our country. And I hope that there will be a propaganda that will propagate truth, decency, legality and kindness.

And now when people are convinced that this past propaganda carried with it so many lies and propagated a lot of things that were not necessary to the people. Now when it is gone, and people don't know what to believe, people think that some kind of propaganda is necessary so that people believe in something.

In my opinion, propaganda was always a weapon in the hands of the politicians who held the fate of the country in their hands. But the people themselves only suffered because this propaganda did not take in to account their interests, but led to something mutually hostile, some kind of confrontation. And if that kind of propaganda disappears, it will only be to the gratitude of ordinary people.

Student Activities

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Douglas Martin, New York Times (4th October, 2008)

(2) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(3) Joseph Darracott, A Cartoon War: World War Two in Cartoons (1989) page 46

(4) Cathy Porter, Alexandra Kollontai: A Biography (1980) pages 326-27

(5) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949) page 227

(6) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 193

(7) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

(8) Stephen Norris, Daily Telegraph (13th April, 2010)

(9) Tim Benson, Boris Efimov: Stalin's favourite cartoonist (2015)

(10) Kevin McNeer, Passport Magazine (June, 2009)

(11) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

(12) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(13) Kevin McNeer, Passport Magazine (June, 2009)

(14) Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) page 402

(15) Mikhail Koltsov, Pravda (19th December, 1937)

(16) Robert Conquest, The Great Terror (1990) page 63

(17) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 239

(18) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) page 251

(19) Marc Jansen, Stalin's Loyal Executioner (2002) page 185

(20) Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die (2008) page 205

(21) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004) pages 352-353

(22) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

(23) Mark Bryant, World War II in Cartoons (1982) page 28

(24) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (July 1941)

(25) Joseph Stalin, radio speech (June, 1941)

(26) Mark Bryant, World War II in Cartoons (1982) page 72

(27) Douglas Martin, New York Times (4th October, 2008)

(28) Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion: World War II (1987) page 218

(29) Joseph Darracott, A Cartoon War: World War Two in Cartoons (1989) page 46

(30) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(31) Kevin McNeer, Passport Magazine (June, 2009)

(32) Joseph Darracott, A Cartoon War: World War Two in Cartoons (1989) page 148

(33) Boris Efimov, letter to David Low (17th September, 1942)

(34) Zbyněk Zeman, Heckling Hitler (1987) page 100

(35) Stephen Norris, Daily Telegraph (13th April, 2010)

(36) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

(37) Boris Efimov, interviewed on PBS (1999)

(38) Kevin McNeer, Passport Magazine (June, 2009)

(39) Tim Benson, Boris Efimov: Stalin's favourite cartoonist (2015)

(40) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(41) Kevin McNeer, Passport Magazine (June, 2009)

(42) Isobel Montgomery, The Guardian (4th October, 2008)

(43) Douglas Martin, New York Times (4th October, 2008)