Priscilla Hiss

Priscilla Fansler, the youngest child of an insurance executive, was born in Philadelphia, in 1904. She studied literature and philosophy at Bryn Mawr. She met Alger Hiss in 1924 when she was on a trip to London. Although they exchanged addresses, she showed no particular interest in him.

In 1926 Priscilla married Thayer Hobson. Later that year she gave birth to a son, Timothy. However, shortly afterwards they separated, and eventually, in January 1929, divorced.

Priscilla found work as an office manager with Time Magazine. She then began a relationship with her colleague, William Brown Meloney, but he was a married man. Priscilla became pregnant and hoped to marry Meloney. He rejected the idea and demanded that she had an abortion. Soon afterwards Meloney broke of his relationship with Priscilla.

Marriage to Alger Hiss

Priscilla now resumed her relationship with Alger Hiss. As G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004), has pointed out: "From her perspective, Alger Hiss may have seemed a more attractive prospect for marriage. He was holding down a very prestigious job, with a decent salary, and he was likely to have a bright future in the legal profession. His continuing to court her, after she had twice rebuffed him for other men, suggested that his attitude to her approached devotion. He had already shown himself to be gifted at helping people in distress. He was a prospective father for her son Timothy." Alger's mother apparently objected to the relationship and sent him a telegram on the day of the wedding, on 11th December, 1929, that warned, "Do Not Take This Fatal Step."

Susan Jacoby has argued in Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009) that the marriage was out of character: "The only unusual step Hiss took as a young man on the way up was his marriage to Priscilla Fansler Hobson, who had a young son by her first husband. Marrying a divorced woman in 1929 was not a move calculated to advance one's social or career prospects... The young attorney was also violating Justice Holmes's well-known rule that his secretaries remain unmarried in order to devote their full attention to him."

Politics of Priscilla Hiss

In 1931 Priscilla and Alger Hiss moved to New York City. Alger joined the firm of Cotton, Franklin, Wright, and Gordon. His biographer, Denise Noe, pointed out: "As a young man, the slim, handsome, and dapper Alger impressed most people as self-confident and more than a few as arrogant. He appeared to have avoided the depression that afflicted other members of his family and achieved success at a young age."

Priscilla Hiss held left-wing opinions and was a member of the Socialist Party of America. Her initial involvement consisted primarily of working at soup kitchens set up for unemployed people who lived in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. She told her husband about "the growing breadlines and soup kitchens, the shanty towns in parks and vacant lots, the beggars that gave sharp reality to accounts of similar and even worse conditions throughout the country." Hiss later claimed: "I had concluded that the Depression was not a natural disaster; it had been avoidable. It was the result of decrepit social structures, of mismanagement and greed. The old order had for long years blocked needed reforms and by its blunders and corruption had precipitated the crash. Our nation, rich in resources and talent, would under vigorous new leadership undo the damage and enact reforms that would prevent future disasters."

In the 1932 Presidential Election he husband supported Franklin D. Roosevelt. "Once Roosevelt's candidacy was announced, I was strongly attracted to his banner, but had no thought that I would do more to advance his cause than urge my friends to vote for him. Nonetheless, I had wanted to do something constructive in a private capacity, something that would help in a small way to set things right. That desire to participate led me to offer my legal skills to a small group of young and similarly motivated New York lawyers who had come together to issue a journal for labor lawyers and those representing hard-pressed farmers."

The Ware Group

Harold Ware, the son of Ella Reeve Bloor, was a member of the American Communist Party and a consultant to the AAA. He established a "discussion group" that included Alger Hiss, Nathaniel Weyl, Laurence Duggan, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Henry H. Collins, Lee Pressman and Victor Perlo. Ware was working very close with Joszef Peter, the "head of the underground section of the American Communist Party." It was claimed that Peter's design for the group of government agencies, to "influence policy at several levels" as their careers progressed".

Susan Jacoby, the author of Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009), has pointed out: "Hiss's Washington journey from the AAA, one of the most innovative agencies established at the outset of the New Deal, to the State Department, a bastion of traditionalism in spite of its New Deal component, could have been nothing more than the rising trajectory of a committed careerist. But it was also a trajectory well suited to the aims of Soviet espionage agents in the United States, who hoped to penetrate the more traditional government agencies, like the State, War, and Treasury Departments, with young New Dealers sympathetic to the Soviet Union (whether or not they were actually members of the Party). Chambers, among others, would testify that the eventual penetration of the government was the ultimate aim of a group initially overseen in Washington by Hal Ware, a Communist and the son of Mother Bloor... When members did succeed in moving up the government ladder, they were supposed to separate from the Ware organization, which was well known for its Marxist participants. Chambers was dispatched from New York by underground Party superiors to supervise and coordinate the transmission of information and to ride herd on underground Communists - Hiss among them - with government jobs."

Whittaker Chambers was a key figure in the Ware Group: "The Washington apparatus to which I was attached led its own secret existence. But through me, and through others, it maintained direct and helpful connections with two underground apparatuses of the American Communist Party in Washington. One of these was the so-called Ware group, which takes its name from Harold Ware, the American Communist who was active in organizing it. In addition to the four members of this group (including himself) whom Lee Pressman has named under oath, there must have been some sixty or seventy others, though Pressman did not necessarily know them all; neither did I. All were dues-paying members of the Communist Party. Nearly all were employed in the United States Government, some in rather high positions, notably in the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Justice, the Department of the Interior, the National Labor Relations Board, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Railroad Retirement Board, the National Research Project - and others."

In 1936, Alger Hiss began working under Cordell Hull in the State Department. Alger was an assistant to Assistant Secretary of State Francis Bowes Sayre and then special assistant to the director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs. When Sayre went to the Philippines in late 1939 as United States High Commissioner. Hiss now became an assistant to Stanley Hornbeck, a special adviser to Hull on Far Eastern affairs.

Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss

Whittaker Chambers stopped being a Soviet spy in 1938. The following year he left the American Communist Party and joined Time Magazine. It soon became clear that Chambers was a strong anti-communist and this reflected the views of the owner of the magazine, Henry Luce, who arranged for him to be promoted to senior editor. Later that year he joined the group that determined editorial policy. Chambers wrote in his memoirs: "My debt and my gratitude to Time cannot be measured. At a critical moment, Time gave me back my life."

In 1939, Chambers met the journalist, Isaac Don Levine. Chambers told Levine that there was a communist cell in the United States government. Chambers recalled in his book, Witness (1952): "For years, he (Levine) has carried on against Communism a kind of private war which is also a public service. He is a skillful professional journalist and a notable ghost writer... From the first, Levine had urged me to take my story to the proper authorities. I had said no. I was extremely wary of Levine. I knew little or nothing about him, and the ex-Communist Party, but the natural prey of anyone who can turn his plight to his own purpose or profit."

In August 1939, Levine arranged for Chambers to meet Adolf Berle, one of the top aides to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He later wrote in Witness: "The Berles were having cocktails. It was my first glimpse of that somewhat beetle-like man with the mild, intelligent eyes (at Harvard his phenomenal memory had made him a child prodigy). He asked the inevitable question: If I were responsible for the funny words in Time. I said no. Then he asked, with a touch of crossness, if I were responsible for Time's rough handling of him. I was not aware that Time had handled him roughly. At supper, Mrs. Berle took swift stock of the two strange guests who had thus appeared so oddly at her board, and graciously bounced the conversational ball. She found that we shared a common interest in gardening. I learned that the Berles imported their flower seeds from England and that Mrs. Berle had even been able to grow the wild cardinal flower from seed. I glanced at my hosts and at Levine, thinking of the one cardinal flower that grew in the running brook in my boyhood. But I was also thinking that it would take more than modulated voices, graciousness and candle-light to save a world that prized those things."

After dinner Chambers told Berle about Alger Hiss being a spy for the Soviet Union. He also told him that Joszef Peter was "responsible for Washington Sector". He also identified the State and Treasury Departments as containing several underground members of the American Communist Party. This included Donald Hiss, Harold Ware, Nathan Witt and Julian Wadleigh. Chambers left the meeting with the impression that Berle was going to pass this information to Roosevelt. Although he did record his conversation with Chambers in a memorandum that suggested a prompt follow-up, nothing happened for several years.

According to Chambers, Berle reacted to the news about Hiss with the comment: "We may be in this war within forty-eight hours and we cannot go into it without clean services." John V. Fleming, has argued in The Anti-Communist Manifestos: Four Books that Shaped the Cold War (2009) Chambers had "confessed to Berle the existence of a Communist cell - he did not yet identify it as an espionage team - in Washington." Berle, who was in effect the president's Director of Homeland Security, raised the issue with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, "who profanely dismissed it as nonsense."

In 1943 the FBI received a copy of Berle's memorandum. Whittaker Chambers was interviewed by the FBI but J. Edgar Hoover concluded, after being briefed on the interview, that Chambers had little specific information. However, this information was sent to the State Department security officials. One of them, Raymond Murphy, interviewed Chambers in March 1945 about these claims. Chambers now gave full details of Hiss's spying activities. A report was sent to the FBI and in May, 1945, they had another meeting with Chambers.

In August 1945, Elizabeth Bentley walked into an FBI office and announced that she was a former Soviet agent. In a statement she gave the names of several Soviet agents working for the government. This included Harry Dexter White and Lauchlin Currie. Bentley also said that a man named "Hiss" in the State Department was working for Soviet military intelligence. In the margins of Bentley's comments about Hiss, someone at the FBI made a handwritten notation: "Alger Hiss".

The following month, Igor Guzenko, a clerk in the Soviet Embassy in Ottowa, defected to the Canadian authorities. He gave them a large number of documents detailing the existence of a large Soviet military intelligence network in Canada. Guzenko was also interviewed by the FBI. He told them that "the Soviets had an agent in the United States in May 1945 who was an assistant to the secretary of state, Edward R. Stettinius." Alger Hiss was Stettinius's assistant at the time."

The FBI sent a report on Hiss to the Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in November 1946. It concluded that Hiss was probably a Soviet agent. Hiss was interviewed by D.M. Ladd, the FBI's Assistant Director, and denied any associations with Communism. The State Department security officials restricted his access to confidential documents, and the FBI wiretapped his office and home phones.

Dean Acheson came under pressure to sack Hiss. Acheson refused to do this and instead contacted John Foster Dulles, who was on the board of directors of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Dulles arranged for Hiss to become president of the organization. At first Hiss refused to go and said he would rather stay and answer his critics. However, Acheson insisted and suggested that "this is the kind of thing which rarely, if ever, gets cleared up."

House of Un-American Activities Committee

On 3rd August, 1948, Whittaker Chambers appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included Alger Hiss.

Chamber's accusations made headline news. Alger Hiss immediately sent a telegram to John Parnell Thomas, HUAC's acting chairman: "I do not know Mr. Chambers, and, so far as I am aware, have never laid eyes on him. There is no basis for the statements about me made to your committee." Hiss asked for the opportunity to "appear... before your committee to make these statements formally and under oath." He also sent a copy of the telegram to John Foster Dulles.

On 5th August, 1948, Hiss appeared before the HUAC: "I am not and never have been a member of the Communist Party. I do not and never have adhered to the tenets of the Communist Party. I am not and never have been a member of any Communist-front organization. I have never followed the Communist Party line, directly or indirectly. To the best of my knowledge, none of my friends is a Communist.... To the best of my knowledge, I never heard of Whittaker Chambers until 1947, when two representatives of the Federal Bureau of investigation asked me if I knew him... I said I did not know Chambers. So far as I know, I have never laid eyes on him, and I should like to have the opportunity to do so."

G. Edward White, the author of Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004) has pointed out: "By his categorical disassociation of himself from even the slightest connection with Communism or Communist-front activities, Hiss set in motion a narrative of his career that he would devote the rest of his life to telling and retelling. In that narrative Hiss was simply a young lawyer who had gone to Washington and became committed to the policies of the New Deal and international peace. His career had been a consistent effort to promote those ideals. He had never been a Communist, and those who were accusing him of being such were seeking to scapegoat him for partisan purposes. They were a pack of liars, and he was their intended victim."

Richard Nixon now joined in the controversy. He argued that "while it would be virtually impossible to prove that Hiss was or was not a Communist... the HUAC... should be able to establish by corroborative testimony whether or not the two men knew each other." Nixon now became the head of a subcommittee to pursue the inquiry of Alger Hiss. HUAC called Hiss back for an executive session in New York City. This time he admitted that he did know Whittaker Chambers but at the time he used the name George Crosley. He also agreed with Chambers's testimony that he had rented him an apartment but denied that he was ever a member of the American Communist Party. Hiss added: "May I say for the record at this point that I would like to invite Mr. Whittaker Chambers to make those same statements out of the presence of the committee, without their being privileged for suit for libel. I challenge you to do it, and I hope you will do it damned quickly."

On 17th August, 1948, Chambers repeated his claim that "Alger Hiss was a communist and may be now." He added, "I do not think Mr. Hiss will sue me for slander or libel." At first Hiss hesitated but he realised that if he did not sue Chambers he would be considered guilty of being a communist. After lengthy discussions with several lawyers, Hiss filed a suit against Chambers on 27th September, 1948.

Alger Hiss Perjury Trial

On 15th December, 1948, the grand jury asked Alger Hiss whether he had known Whittaker Chambers after 1936, and whether he had passed copies of any stolen government documents to Chambers. As he had done previously, Hiss answered no to both questions. The grand jury then indicted him on two counts of perjury. The New York Times reported that he "appeared solemn, anxious, and unhappy" with a grim and worried look". It added that to "observers it seemed obvious that he had not expected to be indicted".

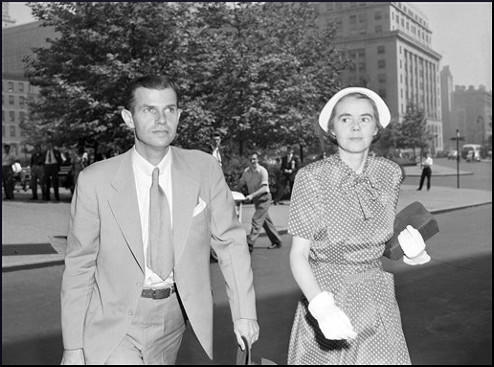

The trial began in May 1949. Hiss later recalled in Recollections of a Life (1988): "Running the gauntlet of the press was, in a sense, a more wearing ordeal than the trials themselves. Inside the courtroom, I not only had the support of my lawyers, but about half of those who daily filled the courtroom were friends or evident sympathizers. But almost every morning as my wife and I left the door of our apartment house at Eighth Street and University Place, unaccompanied by supporters, we were besieged by reporters and often photographers. New York then had several more newspapers than it does now and all the papers and the wire services covered the trials. Dutiful lawyer to the core, I answered no questions, pointing out as politely as possible that it would be inappropriate for me to comment while the case was still in progress. Likewise, I also would not stop to pose for photographers, although they were of course free to take shots as we walked along. In consequence, we were often a public spectacle, Priscilla and I walking resolutely along with photographers walking backward a few paces ahead of us."

Kathryn S. Olmsted, has argued in her book, Red Spy Queen (2002): "Priscilla Hiss would be vilified by reporters, prosecutors, and even alleged friends. Like the women in film noir, like some conservatives' fevered notions of Elizabeth Bentley, she was portrayed as the evil temptress who had led her husband down the road to treason and betrayal - or possibly even framed him to make it appear that he had gone down that road. In the eyes of Alger's friends, the brainy, Bryn Mawr graduate was 'domineering,' 'hard,' and, yes, 'a femme fatale.' But Alger's opponents also saw Priscilla as the source of his problems. Richard Nixon, whose disgust for Priscilla seemed to grow over time, expressed anger in his own account of the Hiss-Chambers affair that he had not questioned Priscilla more intensely." Olmsted quotes Richard Nixon as saying: "if anything, a more fanatical Communist than Hiss."

The first piece of evidence concerned a car purchased by Chambers for $486.75 from a Randallstown car dealer on 23rd November, 1937. Chambers claimed that Hiss had given him $400 to buy the car. The prosecution was able to show that on 19th November Hiss had withdrawn $400 from his bank account. Hiss claimed that this was to buy furniture for a new house. But the Hisses had not signed a lease on any house at that time, and could produce no receipts for the furniture.

The main evidence that the prosecution produced consisted of sixty-five pages of re-typed State Department documents, plus four notes in Hiss's handwriting summarizing the contents of State Department cables. Chambers claimed Alger Hiss had given them to him in 1938 and that Priscilla Hiss had retyped them on the Hisses' Woodstock typewriter. Hiss initially denied writing the note, but experts confirmed it was his handwriting. The FBI was also able to show that the documents had been typed on Hiss's typewriter. According to the The New York Times: "Her testimony centered on two key, prosecution contentions: that she had typed on a family-owned typewriter copies of the secret documents for transmission to Mr. Chambers in 1937 and early 1938, and that she had seen Mr. Chambers after Jan. 1, 1937. She calmly and firmly denied both contentions."

In the first trial Thomas Murphy stated that if the jury did not believe Chambers, the government had no case, and, at the end, four jurors remained unconvinced that Chambers had been telling the truth about how he had obtained the typed copies of documents. They thought that somehow Chambers had gained access to Hiss's typewriter and copied the documents. The first trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict.

The second trial began in November 1949. One of the main witnesses against Hiss in the second trial was Hede Massing. She claimed that at a dinner party in 1935 Hiss told her that he was attempting to recruit Noel Field, then an employee of the State Department, to his spy network. Whittaker Chambers claims in Witness (1952) that this was vital information against Hiss: "At the second Hiss trial, Hede Massing testified how Noel Field arranged a supper at his house, where Alger Hiss and she could meet and discuss which of them was to enlist him. Noel Field went to Hede Massing. But the Hisses continued to see Noel Field socially until he left the State Department to accept a position with the League of Nations at Geneva, Switzerland-a post that served him as a 'cover' for his underground work until he found an even better one as dispenser of Unitarian relief abroad.

Alger Hiss wrote in his autobiography, Recollections of a Life (1988): "Throughout the first trial and most of the second, I was confident of acquittal. But as the second trial wore on, I realized that it was no ordinary one. The entire jury of public opinion, all of those from whom my juries had been selected, had been tampered with. Richard Nixon, my unofficial prosecutor, seeking to build his career on getting a conviction in my case, had from the days of the congressional committee hearings constantly issued public statements and leaks to the press against me. There were moments when I was swept with gusts of anger at the prosecutor's bullying tactics with my witnesses and his devious insinuations in place of evidence - tactics that unfortunately are all too common in a prosecutor's bag of tricks... It was almost unbearable to hear the sneers of the prosecutor as he cross-examined my wife and other witnesses."

Hiss was unhappy with the way he was dealt with in court: "When it was my turn to be cross-examined, the ordeal was of a different sort. Here, court procedures are all weighted in favor of the questioner. The witness may not argue or explain. I was able only to answer directly and briefly, however weighted or hostile the question. My lawyer could object to improper questions, but at the risk of letting the jury get the impression that we were reluctant to have the subject explored. But I was at least not forced to remain mutely impassive, and I was confident that later my lawyer could correct false impressions which bullying cross-examination might leave. It was especially in those moments of provocation triggered by false insinuations that anger and fatigue were to be guarded against. I lost my temper at least once and immediately realized I had erred. The etiquette of the bull ring did not permit the tormented to show even annoyance. I sensed that the jury thought the prosecutor must have scored a point if I reacted so sharply."

Alger Hiss in Lewisburg Penitentiary

The second jury found Hiss guilty of two counts of perjury and on 25th January, 1950, he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment. The Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was asked later that day about the Hiss trial. He replied: "Mr. Hiss's case is before the courts, and I think it would be highly improper for me to discuss the legal aspects of the case, or the evidence, or anything to do with the case. I take it the purpose of your question was to bring something other than that out of me... I should like to make it clear to you that whatever the outcome of any appeal which Mr. Hiss or his lawyers may take in this case, I do not intend to turn my back on Alger Hiss. I think every person who has known Alger Hiss, or has served with him at any time, has upon his conscience the very serious task of deciding what his attitude is, and what his conduct should be. That must be done by each person, in the light of his own standards and his own principles... My friendship is not easily given, and not easily withdrawn."

Alger Hiss's appeal was unanimously denied and on 22nd March, 1951, he was sent to a maximum security federal facility in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. "Often while I was at Lewisburg, and since, I have remarked upon the similarities between prison and the army. Both institutions are designed to control large numbers of men. Both supply food, clothing, and shelter for large groups. Both must organize the activities of their charges and provide some recreation to balance the workload. Most important of all, both must impose strict discipline in order to ensure that these functions are carried out. An essential element in the successful implementation of discipline by each institution is the process of depersonalization. Privacy disappears; there is no individuality of dress; food and activities are as uniform as the clothing. At Lewisburg we marched in columns of twos to meals and to movies."

Priscilla Hiss: 1954-1958

Alger Hiss lost his license to practice law and his fear that "informal blackballing" would make it difficult for him to obtaining employment. As Alger later pointed out, "Priscilla wanted us to flee the scenes of her torment. She suggested we change our names and try to get posts as teachers at some remote experimental school oblivious to public opinion." Hiss disagreed and wanted as much publicity as possible to show the world he had not given government secrets to the Soviets. As part of this campaign he published his memoirs, In the Court of Public Opinion (1957).

In 1957 Fred J. Cook was asked by Carey McWilliams, the editor of the Nation Magazine, to look into the Alger Hiss case. Cook replied: "My God, no, Carey. I think he's as guilty as hell. I wouldn't touch it with a ten-foot pole." Two weeks later McWilliams contacted Hiss again. "Look, I have a proposition to make you. I know how you feel about the case, but I've talked to a lot of people who I trust. They say if anybody looked hard at the evidence they'd have a different opinion. You're known as a fact man. Will you do this for me? No obligation. Will you at least look at the facts?"

Cook agreed and he later recalled that he changed his mind on the case after he examined the testimony of Whittaker Chambers. He later recalled: "Well, here was a guy who committed perjury so many times - admittedly so. I didn't see how anybody could trust anything he said. The typing process as he described it didn't make sense. Why would the Hisses spend all that time typing the documents when they supposedly had a whole system set up to photograph them? It was like that with the whole damn thing. When you looked at the government's case, it didn't make any sense down the line, anywhere. One after another as the arguments against Hiss fell apart, I realized I had been brainwashed by my own profession. Until then, I thought that if the story against him was generally accepted, then it had to be true. I should have known better, but I didn't."

Cook's article on Alger Hiss was published in Nation Magazine on 21st September, 1957. He argued that Hiss was a victim of McCarthyism and was not guilty of the accusations made by Whittaker Chambers who had accused Hiss of being a Soviet spy while working for the State Department. Hiss later commented: "It was the times. There was this great wave of hysteria about the great Russian communist menace, and I think the jury was susceptible to that. A lot of average people were. When you have an hysteria like that built in and bastards like Joe McCarthy are beating the drums, it affects the average person. They figure when there's smoke, there has to be fire."

Cook argued that both the FBI and HUAC had political reasons for victimizing Hiss. He also suggested that the FBI would have had the resources to build a typewriter with a typeface that appeared to match that of the Hiss family. Hiss, Cook concluded, might have been "an American Dreyfus, framed at the highest level of justice for political advantage". Cook's book on the case, The Unfinished Story of Alger Hiss, appeared in 1958.

In 1958 Priscilla Hiss asked her husband to leave the family home. Alger spent "the next several years in rented rooms and friend's apartments". However, when he became involved with another woman in the 1960s she refused to divorce him. Tony Hiss has pointed out that his mother "alternated between cursing Al for leaving and making plans for what she'd do after he came back."

According to William G. Blair: "After Mr. Hiss's conviction, she worked as an editor at several publishing houses in New York City, including the Golden Press, the children's book division of the Western Publishing Company. Later, she became involved in Democratic politics, serving with Community Board in Greenwich Village, the Village Independent Democrats and the Democratic County Committee of New York County."

Priscilla Hiss: A Soviet Spy?

In 1971, the historian, Allen Weinstein, wrote an article where he argued that he was not convinced that Alger Hiss was guilty, but doubted whether Hiss could be proven innocent given the evidence about the case that had thus far been made public. He suggested that a definitive understanding of the case would not be possible without the release of "the executive files of HUAC," "the relevant FBI records," and "the grand jury records." Weinstein contacted Hiss and he agreed for him to have access to his defense files. In 1972 he supported Weinstein's Freedom of Information suit to obtain FBI and Justice Department files on the case.

Allen Weinstein began his investigation of Alger Hiss with the belief that he was innocent. Hiss agreed to cooperate with Weinstein in his attempts to obtain information from the FBI. As Weinstein pointed out: "Given the fact that I published an article which had argued for his innocence, and given the fact that... my premise was that he seemed to be innocent. Why not cooperate fully with me? I expected to be finding evidence that would help clear him."

The FBI refused to disclose these documents and so Weinstein concentrated on investigating Hiss's defense files. He discovered that his lawyer in the first perjury trial, Edward McLean (Debevoise, Plimpton and McLean) had doubts about his innocence. McLean believed that Priscilla Hiss was probably a Soviet spy and that Hiss was "at the very least, Alger was shielding Priscilla Hiss". His lawyers were concerned that he had originally lied about her membership of the Socialist Party of America. They were also convinced that she was fairly close to Whittaker Chambers. In February, 1950, Mclean withdrew from the case. William Marbury (Marbury, Miller and Evans) was also highly skeptical of Priscilla's evidence. Marbury was interviewed by Weinstein in 1974: "He (Marbury) had begun to have some very serious questions about the completeness of Hiss's account."

Weinstein also interviewed Meyer Schapiro, a close friend of Chambers (he had died in 1961). He confirmed that Chambers had a close association with Hiss. He was also with Chambers when he purchased a rug for Hiss in December 1936. Hiss had claimed that he had broken off his relationship with Chambers in 1935. Weinstein checked with the Massachusetts Importing Company that had sold the rug to Chambers and they agreed that the transaction took place in 1936.

After a legal struggle the FBI began releasing files on the Hiss case in October 1975. In February 1976 Weinstein told the New Republic that the files showed no evidence of an FBI conspiracy, only that the FBI had occasionally been inept or incompetent. Other documents released included the transcript of an interview with William Edward Crane, a FBI informant and a member of Chambers's network. He confirmed much of what Chambers had said about Hiss. Weinstein told the New York Times that "a preliminary look (at the declassified files) fails to bear out the most commonly raised conspiracy claims" against the FBI.

Allen Weinstein met Hiss in March 1976. He told him: "When I began working on this book four years ago, I thought that I would be able to demonstrate your innocence, but unfortunately, I have to tell you, that I cannot; that my assumption was wrong... I had a number of unresolved questions about Whittaker Chambers's testimony when I began. Even then I wasn't convinced that either of you had told the complete truth. I thought, however, that you had been far more truthful than Chambers. But after interviewing scores of people, looking at the FBI files, finding new evidence in private hands, and reading all of your defense files, every important question that had existed in my mind about Chambers's veracity on key points arose, and... none of them have been answered satisfactorily." Hiss replied: "I've always known you were prejudiced against me."

Priscilla Hiss died in October 1984.

Primary Sources

(1) Susan Jacoby, Alger Hiss and the Battle for History (2009)

The only unusual step Hiss took as a young man on the way up was his marriage to Priscilla Fansler Hobson, who had a young son by her first husband. Marrying a divorced woman in 1929 was not a move calculated to advance one's social or career prospects... The young attorney was also violating Justice Holmes's well-known rule that his secretaries remain unmarried in order to devote their full attention to him. In a letter to Frankfurter about his wedding (which Hiss had concealed from Holmes until the last minute), Alger certainly displayed a talent for manipulation and prevarication. "I learned some ten hours before my marriage... that the justice had definitely stipulated that his secretaries be unmarried," Hiss told Frankfurter. "Of course, I appreciated that.. the secretary's personal affairs must never impinge a "scintilla" on the justice's time or energy, and I - rather we - laid meticulous plans until the last moment. As part of these plans the justice was not informed until the last moment... I in no wise sensed any fiat negative to marriage qua marriage - of inconsiderateness which might reasonably grow out of a secretary's marrying he did gently complain, I suppose."

(2) G. Edward White, Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004)

The first of Hiss's looking-glass wars confronted him with the awkward option of putting off his marriage to Priscilla Hiss, at a time when circumstances had combined to make her suddenly available to him, or violating one of the conditions of his employment with justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Once Priscilla, with whom he had been smitten for many years, signaled her willingness to marry him, Hiss knew which of the options he would choose. He then had to figure out how to break Holmes's no-marriage rule without enraging Holmes. His strategy was to plan a virtually secret marriage while pretending that he did not know about Holmes's rule. This was to be a common technique of Hiss's in his looking-glass wars. He not only denied having a secret life that many people would have found objectionable. He also sought to project the image of person who, by reason of his character and personality, couldn't have had such a life.

(3) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952)

It was early evening when I reached the Hisses' house, probably between six and seven o'clock. They were then living on Volta Place in Georgetown, in a house whose narrow end faced the street. It was, in fact, flush with the sidewalk. I went in through the little gate, at the right side of the house. A colored maid, probably Claudia Catlett, who was a witness for Hiss at his trials, came to the door. She said that neither Mr. nor Mrs. Hiss was at home. I left. But as I stood for a moment in indecision on the sidewalk, Priscilla Hiss drove up. She headed in to the curb on a slant to park. The headlights swept the sidewalk and I stepped into the beam so that Priscilla could see me clearly and would not be frightened by a loitering figure.

Her greeting was pleasant but not effusive, and I decided at once that Alger Hiss had been warned of my break. We went into the house together. Yet there was nothing in Priscilla's manner, as we sat chatting in the living room, that enabled me to tell what Alger really did know. Then Timmie joined us. Timmie is Timothy Hobson, Priscilla Hiss's son by her first marriage. Timmie was delighted to see me.

I had to go to the bathroom. Priscilla followed me upstairs. The bathroom was at the front of the house, facing the street. Directly to the right of the bathroom door, there was a bedroom door. A telephone was on a little table near the door. As I went into the bathroom, Priscilla went into the bedroom. I closed the bathroom door and thought: "This situation is tight." Before I washed my hands, I opened the bathroom door halfway. Priscilla was speaking in a very low voice into the telephone. I walked directly up to her. She hung up. We went downstairs in silence.

At that nerve-tingling moment, Alger Hiss came home. We were in the living room and he saw me the moment he came into the house. He was surprised, of course, and his surprise showed in his eyes. But he smiled pleasantly, said: "How do you do," and made me the little bow with his head and shoulders that he sometimes made when he was being restrained. It was both whimsical and grave.

We went in almost at once to supper. The dining room was also at the front of the house. The light supper, which had been intended for three, and was stretched for four, was quickly over. With Timmie present and the maid serving, we again made the kind of random talk that Priscilla and I had had before Alger arrived. Again, I do not remember just what we talked about, but I seem to recall that Timmie, who had never taken much interest in athletics, was trying out for the wrestling team at his school, and wanted for Christmas, or had just bought, some wrestling shoes.

Timmie left the table while we had our coffee and I said good night to him - in effect good-bye, for I have never seen him since. Once Timmie was gone some question was asked which I answered in the faintly foreign tone that I had always used in the underground. The reaction was electric: "You don't have to put on any longer. We have been told who you are." To understand what was meant, it is necessary for me to explain that Alger Hiss, like everybody else in the Washington underground, supposed that I was some kind of European. I do not want to interrupt the narrative to explain how this was possible. But during the Grand jury hearings in 1948, one of the former underground people was brought into the witness waiting room so that he could hear me speak because, while I looked like the man he knew as Carl, I spoke like an American, and the man he knew as Carl spoke like a European.

The angry answer at the dinner table meant that two facts were known: I was an American; I had broken with the Communist Party. Alger, who was sitting at the head of the table, to my right, tried to dispel the awkwardness. He said something to this effect: "It is a pity that you broke. I am told that you were about to be given a very important post. Perhaps if you went to the party and made your peace, it could still be arranged." I thought: "Alger has been told to say that to me." The "important post" was perhaps Bykov's old project of the sleeper apparatus now doing service as bait. I smiled and said that I did not think I would go to the party.

I began a long recital of the political mistakes and crimes of the Communist Party: the Soviet Government's deliberate murder by mass starvation of millions of peasants in the Ukraine and the Kuban; the deliberate betrayal of the German working class to Hitler by the Communist Party's refusal to co-operate with the Social Democrats against the Nazis; the ugly fact that the German Communist Party had voted in the Reichstag with the Nazis against the Social Democrats; the deliberate betrayal of the Spanish Republican Government, which the Soviet Government was only pretending to aid while the Communists massacred their political enemies in the Spanish prisons. This gigantic ulcer of corruption and deceit had burst, I said, in the great Russian purge when Stalin had consolidated his power by massacring thousands of the best men and minds in the Communist Party on lying charges.

I may have spoken for five or ten minutes. I spoke in political terms because no others would have made the slightest impression on my host. I spoke with feeling, and sometimes with slow anger as the monstrous picture built up. Sometimes Alger said a few objecting words, soberly and a little sorrowfully. Then I begged him to break with the Communist Party.

Suddenly, there was another angry flare-up: "What you have been saying is just mental masturbation."

I was shocked by the rawness of the anger revealed and deeply hurt. We drifted from the dining room into the living room, most unhappy people. Again, I asked Alger if he would break with the Communist Party. He shook his head without answering. There was nothing more to say. I asked for my hat and coat. Alger walked to the door with me. He opened the door and I stepped out. As Alger stood with his hand on the half-open door, he suddenly asked: "What kind of a Christmas will you have?" I said: "Rather bleak, I expect." He turned and said something into the room: "Isn't there...?" I did not catch the rest. I heard Priscilla move. Alger went into the room after her. When he came back, he handed me a small cylindrical package, three or four inches long, wrapped in Christmas paper. "For Puggie," he said. Puggie is my daughter's nickname. That Alger should have thought of the child after the conversation we had just had touched me in a way that I can only describe by saying: I felt hushed.

We looked at each other steadily for a moment, believing that we were seeing each other for the last time and knowing that between us lay, meaningless to most of mankind but final for us, a molten torrent - the revolution and the Communist Party. When we turned to walk in different directions from that torrent, it would be as men whom history left no choice but to be enemies.

As we hesitated, tears came into Alger Hiss's eyes - the only time I ever saw him so moved. He has denied this publicly and derisively. He does himself an injustice - by the tone rather than by the denial, which has its practical purpose in the pattern of his whole denial. He should not regret those few tears, for as long as men are human, and remember our story, they will plead for his humanity.

(4) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999)

Hiss and Chambers worked together as Soviet source and courier from late 1934 until the latter's defection from the underground in 1938, and despite extraordinary differences in background, careers, and interests, they (and their wives) developed a personal bond. Alger Hiss was born into a prominent Baltimore family, disrupted at an early age by his father's suicide. Even as a young man, Hiss impressed others as intelligent, handsome, and extremely well mannered. He excelled both as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University and in his studies at Harvard Law School, where he became a protégé of Professor (and later Supreme Court Justice) Felix Frankfurter. Through Frankfurter, Hiss obtained a coveted clerkship with the Court's aging eminence justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. By then, Hiss had married a New York writer and art historian, Priscilla Fansler, who later assisted in his Soviet underground work by retyping State Department documents for transmission. Alger Hiss worked for several years after his clerkship at a prominent New York law firm before heading to Washington and a post with the AAA in 1933, and both he and Priscilla were also active members of various radical groups. Because of this background, the Hisses later mixed easily with New Dealers of their own generation and with older, more influential figures in the Roosevelt Administration.

Prior to meeting Alger Hiss, Whittaker Chambers's life had been much less charmed and far more turbulent. He, too, had lacked a stable paternal relationship-his father was a minor journalist who was frequently absent from home and, when there, frequently drunk. From his earliest schooldays, Chambers displayed an unusual ability as a writer and linguist, and while attending Columbia College during the 1920s, he cultivated a circle of friends largely focused on literary and artistic careers. But Chambers dropped out of college to lead a bohemian existence in and around New York City for several years until he gravitated toward membership in the CPUSA during the mid-1920s where, he found a niche as a journalist, writing first for the Daily Worker and then for the New Masses, and marrying Esther Shemitz, another young radical and an aspiring artist.

In the spring of 1932, Chambers was recruited for "secret work" by a leading party official, Max Bedacht, a member of the CPUSA's Central Committee, who instructed him, with Chambers's acquiescence, to leave the New Masses's staff, where Chambers had become a well-known "proletarian writer" and translator'` and to disappear from other "open" Communist circles. Bedacht led Chambers to a meeting with an old friend from the Daily Worker, John Loomis Sherman, who was already involved in covert activities. Sherman, in turn, introduced Chambers that same day to Valentin Markin ("Herbert"), a Russian operative with whom he worked as an agent until Markin's death in August 1934. The subsequent disbanding of Markin's network led Joszef Peter that same month to identify a replacement assignment for Chambers as a Washington-to-New York courier."

After their initial meeting, Hiss and Chambers, source and courier, developed a measure of rapport not unlike the personal link between Laurence Duggan and Itzhak Akhmerov. During the summer of 1935 for example, Chambers ("Karl" to the Hisses) lived for several months in an apartment rented by Hiss, and on other occasions, Esther and Whittaker Chambers and their infant son stayed with the Hisses while looking for their own apartment At one point, Hiss even transferred to Chambers title to an old automobile he was no longer using, and several years later made Chambers a loan to buy another car.

(5) Alger Hiss, Recollections of a Life (1988)

Running the gauntlet of the press was, in a sense, a more wearing ordeal than the trials themselves. Inside the courtroom, I not only had the support of my lawyers, but about half of those who daily filled the courtroom were friends or evident sympathizers. But almost every morning as my wife and I left the door of our apartment house at Eighth Street and University Place, unaccompanied by supporters, we were besieged by reporters and often photographers. New York then had several more newspapers than it does now and all the papers and the wire services covered the trials. Dutiful lawyer to the core, I answered no questions, pointing out as politely as possible that it would be inappropriate for me to comment while the case was still in progress. Likewise, I also would not stop to pose for photographers, although they were of course free to take shots as we walked along. In consequence, we were often a public spectacle, Priscilla and I walking resolutely along with photographers walking backward a few paces ahead of us.

Our route was along Eighth Street to the Astor Place subway station of the Lexington Avenue line. One morning the harassment by the press did not end at the subway entrance. Photographers followed us through the turnstiles and into our car. Startled passengers deserted our part of the car as flashbulbs popped.

There were times when we found ourselves in the same subway car with one or more members of the jury, whom we studiously avoided. We could, however, see that the jurors were ignoring the judge's injunction not to read press accounts of the case.

When we arrived at the Federal Court Building we were frequently met by other reporters or idly curious bystanders as we walked up the long flights of steps outside the building and then along the corridors. In the elevator we were accompanied by curious spectators, some headed for the show my trial afforded. Then the whole thing was repeated as we made our way home at the end of the day.

(6) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002)

Elizabeth Bentley was the first "red spy queen," but other accused "lady spies" would receive similar treatment from the media. The cultural construction of the "spy queen" in these cases reveals similar tensions about masculinity and changing gender roles in the early years of the Cold War.

Just a few months later, for example, Priscilla Hiss would be vilified by reporters, prosecutors, and even alleged friends. Like the women in film noir, like some conservatives' fevered notions of Elizabeth, she was portrayed as the evil temptress who had led her husband down the road to treason and betrayal - or possibly even framed him to make it appear that he had gone down that road. In the eyes of Alger's friends, the brainy, Bryn Mawr graduate was "domineering," "hard," and, yes, "a femme fatale." But Alger's opponents also saw Priscilla as the source of his problems. Richard Nixon, whose disgust for Priscilla seemed to grow over time, expressed anger in his own account of the Hiss-Chambers affair that he had not questioned Priscilla more intensely because she was "if anything, a more fanatical Communist than Hiss." In 1986, Nixon wrote in the New York Times that this was a common pattern for Communist couples: "the wife is often more extremist than the husband."

(6) William G. Blair, The New York Times (15th October, 1984)

Priscilla Hiss, the wife of Alger Hiss, who steadfastly defended her husband at his two trials for perjury, died yesterday at St. Vincent's Hospital and Medical Center in Manhattan. She was 81 years old on Saturday.

Mrs. Hiss had been ill since suffering a stroke in 1981. She had lived in Greenwich Village since 1947 and at the Village Nursing Home since 1982.

Mrs. Hiss was thrust into the limelight in 1948 when her husband, a former State Department official, was accused of being a spy by Whittaker Chambers, an admitted former courier for a Soviet spy ring. Throughout Mr. Hiss's two perjury trials, in 1948 and 1949-50, and in the years that followed, she staunchly maintained her husband's innocence.

His first trial ended in a hung jury, but Mr. Hiss was convicted of perjury at his second trial for denying to a grand jury that he had passed secret, State Department documents to Mr. Chambers. He served 44 months in prison.

Mrs. Hiss testified at both trials. Her testimony centered on two key, prosecution contentions: that she had typed on a family-owned typewriter copies of the secret documents for transmission to Mr. Chambers in 1937 and early 1938, and that she had seen Mr. Chambers after Jan. 1, 1937. She calmly and firmly denied both contentions.

She married Mr. Hiss in 1929. They separated in 1959 and lived apart but did not divorce.

Before the notoriety of the trials swept over her life, Mrs. Hiss, who shared with her husband a strong interest in bird watching, had worked as an office manager for Time magazine in New York City, and had taught English at the Potomac School in Washington and at the Dalton School in New York. She was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and received a master's degree in English literature from Yale University.

After Mr. Hiss's conviction, she worked as an editor at several publishing houses in New York City, including the Golden Press, the children's book division of the Western Publishing Company.

Later, she became involved in Democratic politics, serving with Community Board in Greenwich Village, the Village Independent Democrats and the Democratic County Committee of New York County.

Besides her husband, she is survived by a son, Tony Hiss of New York, and a son by a previous marriage, Timothy Hobson of Gillette, Wyo.