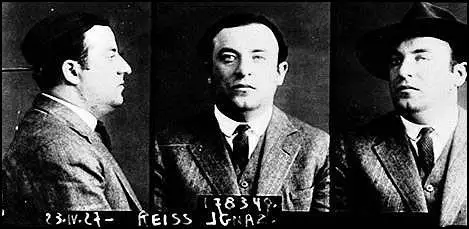

Ignaz Reiss

Ignace Poretsky (Ignace Reiss) was born in Podwołoczyska in 1899. His parents were Jewish and as a boy became close friends with Walter Krivitsky. He described him as a tall and gentle boy, with dark hair and very pale blue eyes. Reiss and Krivitsky developed left-wing views. As a teenager Ignace visited Leipzig where he met fellow socialists, including Gertrude Schildbach.

During the First World War he studied for a degree from the Faculty of Law at the University of Vienna. He was a strong supporter of the Russian Revolution. As Krivitsky pointed out: "In 1917 I was a youngster of eighteen, and the Bolshevik Revolution came to me as an absolute solution to all problems of poverty, inequality and justice."

In 1918, Ignace Reiss returned to his hometown, where he worked for the railway. Reiss was deeply influenced by the political philosophy of Rosa Luxemburg and in 1919 he joined the Communist Workers' Party of Poland (KPRP). Reiss represented the KPRP at the Third International in March 1919. Here he met fellow Polish revolutionary, Felix Dzerzhinsky, who was now head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka). In 1921 he agreed to work for Dzerzhinsky as a spy.

Secret Agent

Ignaz met and married Elsa Bernaut. In 1922 he was arrested and charged with espionage. Facing a five-year sentence he managed to escape on the way to prison. Reiss was now sent to work in Berlin. During this period he became friends with Karl Radek, Angelica Balabanoff, Theodore Maly, Richard Sorge and Hans Brusse. In 1927, he returned briefly to the Soviet Union, where he received the Order of the Red Banner. Reiss spent time in Vienna before obtaining a post in Moscow, where he joined the Polish section of the Comintern.

In 1932 Reiss became a NKVD official in Paris. He was therefore out of the country when Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and fourteen other defendants had been executed after they were found guilty of trying to overthrow Joseph Stalin. This was the first of the Show Trials and the beginning of the Great Purge. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "The Zinoviev-Kamenev trial of August 1936 defamed Lenin's confederates, in a sense the founding fathers of that state. When he learned of the trial's monstrous conclusion, the death penalty for all sixteen defendants, he felt he could no longer belong."

The Great Purge

Reiss met his old friend, Walter Krivitsky, who was also working for the Russian Secret Police, and suggested that they should both defect in protest as a united demonstration against the purge of leading Bolsheviks. Krivitsky rejected the idea. He suggested that the Spanish Civil War, which had just begun, would probably revive the old revolutionary spirit, empower the Comintern and ultimately drive Stalin from power. Krivitsky also made the point that that there was no one to whom they could turn. Going over to Western intelligence services would betray their ideals, while approaching Leon Trotsky and his group would only confirm Soviet propaganda, and besides, the Trotskists would probably not trust them.

In December 1936, Nikolai Yezhov established a new section of the NKVD named the Administration of Special Tasks (AST). It contained about 300 of his own trusted men from the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Yezhov's intention was complete control of the NKVD by using men who could be expected to carry out sensitive assignments without any reservations. The new AST operatives would have no allegiance to any members of the old NKVD and would therefore have no reason not to carry out an assignment against any of one of them. The AST was used to remove all those who had knowledge of the conspiracy to destroy Stalin's rivals. One of the first to be arrested was Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD.

Within the administration of the ADT, a clandestine unit called the Mobile Group had been created to deal with the ever increasing problem of possible NKVD defectors, as officers serving abroad were beginning to see that the arrest of people like Yagoda, their former chief, would mean that they might be next in line. The head of the Mobile Group was Mikhail Shpiegelglass.

A law was also passed that stated that the crime of defection was a capital offence. The relatives of defectors were also to be punished by confiscation of property and five to ten years in confinement. If the defector divulged state secrets or collaborated in any way with a foreign state, his crime was considered all the more unacceptable and his relatives, whether or not they knew of his actions, could be executed.

Reiss's wife, Elsa Poretsky, visited Moscow in early 1937. She noted that: "The Soviet citizen does not rejoice in the splendor, he does not marvel at the blood trials, he hunches down deeper, hoping only perhaps to escape ruin. Before every Party member the dread of the purge. Over every Party member and non-Party member the lash of Stalin. Lack of initiative it's called, then lack of vigilance - counter-revolution, sabotage, Trotskyism. Terrified to death, the Soviet man hastens to sign resolutions. He swallows everything, says yea to everything. He has become a clod. He knows no sympathy, no solidarity. He knows only fear."

By the summer of 1937, over forty intelligence agents serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Krivitsky realised that his life was in danger. Alexander Orlov, who was based in Spain, had a meeting with fellow NKVD officer, Theodore Maly, in Paris, who had just been recalled to the Soviet Union. He explained his concern as he had heard stories of other senior NKVD officers who had been recalled and then seemed to have disappeared. He feared being executed but after discussing the matter he decided to return and take up this offer of a post in the Foreign Department in Moscow. General Yan Berzin, Dmitri Bystrolyotov and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, were also recalled. Maly, Antonov-Ovseenko and Berzen were all executed.

Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) has pointed out: "Ignace Reiss suddenly realised that before long he, too, might well be next on the list for liquidation. He had been loyal to the Soviet Union, he had carried out all tasks assigned to him with efficiency and devotion, but, though not a Trotskyite, he was the friend of Trotskyites and opposed to the anti-Trotsky campaign. One by one he saw his friends compromised on some trumped-up charge, arrested and then either executed or allowed to disappear for ever. When Reiss returned to Europe he must already have known that he had little choice in future: either he must defect to safety, or he must carry on working until he himself was liquidated."

Recalled to Moscow

Walter Krivitsky was also recalled to Moscow. He later claimed that he took the opportunity to "find out at firsthand what was going on in the Soviet Union". Krivitsky wrote that Joseph Stalin had lost the support of most of the Soviet Union: "Not only the immense mass of the peasants, but the majority of the army, including its best generals, a majority of the commissars, 90 percent of the directors of factories, 90 percent of the Party machine, were in more or less extreme degree opposed to Stalin's dictatorship."

Krivitsky met up with Ignaz Reiss in Rotterdam on 29th May, 1937. He told Reiss that Moscow was a "madhouse" and that Nikolai Yezhov was "insane". Krivitsky agreed with Reiss that the Soviet Union had "devolved into a Fascist state" but refused to defect. Krivitsky later explained: "The Soviet Union is still the sole hope of the workers of the world. Stalin may be wrong. Stalins will come and go, but the Soviet Union will remain. It is our duty to stick to our post." Reiss disagreed with Krivitsky and said if that was his view he would go it alone. Elsa Poretsky also began to doubt the loyalty of Krivitsky. She began to wonder why he had been allowed to leave Moscow. She told her husband: "No one leaves the Soviet Union unless the NKVD can use him."

In July 1937 Ignaz Reiss received a letter from Abram Slutsky and was warned that if he did not go back to Moscow at once he would be "treated as a traitor and punished accordingly". It was therefore decided to defect. Elsa rented a house in Finhaut, a picturesque village in southern Switzerland, just over the border from France and Ignaz took a room in a Paris hotel.

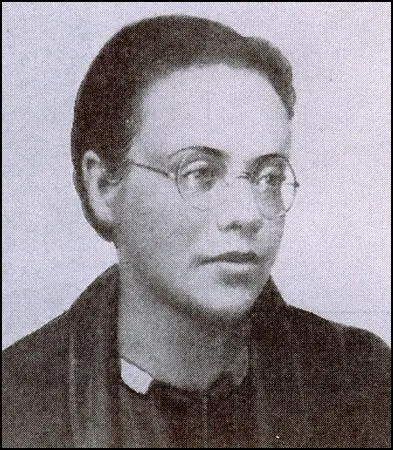

Reiss also received a letter from Gertrude Schildbach. At the time she was living in Rome and she asked if she could see Reiss. He agreed and then went to a meeting with Henricus Sneevliet in Amsterdam. Sneevliet later told Victor Serge and his fellow Trotskyists that "Ignace Reiss was warning us that we were all in peril, and asking to see us. Reiss was at present hiding in Switzerland. We arranged to meet him in Rheims on 5 September 1937."

Letter to Stalin

Reiss wrote a series of letters that he gave in to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Union because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. "Up to this moment I marched alongside you. Now I will not take another step. Our paths diverge! He who now keeps quiet becomes Stalin's accomplice, betrays the working class, betrays socialism. I have been fighting for socialism since my twentieth year. Now on the threshold of my fortieth I do not want to live off the favours of a Yezhov. I have sixteen years of illegal work behind me. That is not little, but I have enough strength left to begin everything all over again to save socialism. ... No, I cannot stand it any longer. I take my freedom of action. I return to Lenin, to his doctrine, to his acts." These letters were addressed to Joseph Stalin and Abram Slutsky.

Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Walter Krivitsky that Reiss had gone over to the Trotskyists and described him meeting Henricus Sneevliet in Amsterdam. Krivitsky assumed from this information that Stalin had a spy within Sneevliet's group. Krivitsky correctly guessed that this was Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky and another NKVD agent, Theodore Maly, tried to contact Reiss. Recently released NKVD files show that Shpiegelglass ordered Maly to take an iron and beat Reiss to death in his hotel room. Maly refused to carry out this order and criticised Shpiegelglass in his report to Moscow.

Shpiegelglass was instructed to organize the assassination of Reiss. According to Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001): "On learning that Reiss had disobeyed the order to return and intended to defect, an enraged Stalin ordered that an example be made of his case so as to warn other KGB officers against taking steps in the same direction. Stalin reasoned that any betrayal by KGB officers would not only expose the entire operation, but would succeed in placing the most dangerous secrets of the KGB's spy networks in the hands of the enemy's intelligence services. Stalin ordered Yezhov to dispatch a Mobile Group to find and assassinate Reiss and his family in a manner that would be sure to send an unmistakable message to any KGB officer considering Reiss's route."

Reiss now joined Elsa Poretsky in Finhaut. According to Elsa his hair had turned white during the ten days he had been hiding in France. After several days he showed his wife a copy of the letter he had sent to Stalin. She now realized that "our world was gone forever, we had no past, we had no future, there was only the present." They had no income and nowhere to go. They also had no legal status anywhere.

Assassinated

Reiss wrote to Henricus Sneevliet and suggested a meeting in Reims on 5th September. He also contacted Gertrude Schildbach and arranged to see her at a cafe in Lausanne. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "They found Schildbach unusually well dressed and full of stories about a rich industrialist she was going to marry, stories which they took with a dash of salt. They sat by a window, Elsa beside her and Ignace across, as she chattered nervously about her urgent matter - her desire to defect. Ignace advised her to get in touch with the Trotskyists."

Elsa returned to their home in Finhaut and Reiss planned to take the train to Reims to meet Sneevliet. Victor Serge later wrote: "We arranged to meet him in Reims on 5 September 1937. We waited for him at the station buffet, then at the post office. He did not appear. Puzzled, we wandered through the town, admiring the cathedral... drinking champagne in small cafes, and exchanging the confidences of men who have been saddened through a surfeit of bitter experiences."

Ignaz Reiss and Gertrude Schildbach went for supper outside of town. They left the restaurant and set off on foot. A car pulled up bearing two NKVD agents, Francois Rossi and Etienne Martignat. One was driving, the other - holding a machine-gun. Reiss was shot seven times in the head and five times in the body. The assassins fled, not bothering to check out of the hotel in Lausanne. They abandoned the car in Berne. The police found a box of chocolates, laced with strychnine, in the hotel room. It is believed these were intended for Elsa and her son Roman.

Schildbach was arrested in December, 1938. She received a sentence of eight months' imprisonment for her involvement in the crime. On her release she moved to the Soviet Union. It is believed that she was sent to a prison camp where she died.

Boris Nicolaevsky decided to carry out an investigation to discover who the traitor was in the group. He approached another defector, Walter Krivitsky, and asked him for his views. Krivitsky suggested that Victor Serge was the traitor. We now know it was Mark Zborowski. As Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004), has pointed out: "Not satisfied with Krivitsky's abstract logic, Nicolaevsky pressed him to make a more specific report in short, to name his chief suspect. Krivitsky obliged in October 1938 with a personal letter to Nicolaevsky, again writing with painful deliberation and pedantic punctiliousness, but giving weighty reasons for suspecting Victor Serge. The verdict seems wrongheaded and even ironic today, in the light of what is known about Mark Zborowski, yet history has not completely cleared Serge of suspicion, despite apologies in the literature about his political lightheadedness and naive artist's indiscretion. Krivitsky points out that there was no other case in Soviet history of a man first arrested and imprisoned as a Trotskyist, then given not only his freedom, but also permission to travel abroad, all this at a time when other accused Trotskyists were suffering monstrous persecutions."

Primary Sources

(1) Edward P. Gazur, Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001)

The case of Ignaz Reiss, whose real name was Poretsky, was the first to come to Orlov's attention towards the end of July 1937. Reiss was the KGB illegal rezident in Belgium when he was summoned back to Moscow. Reiss had the advantage of having his wife and daughter with him when he decided to defect. In July of that year, he sent a letter to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Government because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. Orlov learned the details of Reiss's letter and decision to defect through his close contacts at the Soviet Embassy in Paris. He would later learn the conclusion of the matter through the same source.

On learning that Reiss had disobeyed the order to return and intended to defect, an enraged Stalin ordered that an example be made of his case so as to warn other KGB officers against taking steps in the same direction. Stalin reasoned that any betrayal by KGB officers would not only expose the entire operation, but would succeed in placing the most dangerous secrets of the KGB's spy networks in the hands of the enemy's intelligence services. Stalin ordered Yezhov to dispatch a Mobile Group to find and assassinate Reiss and his family in a manner that would be sure to send an unmistakable message to any KGB officer considering Reiss's route.

The task was of such a high priority that Yezhov placed his Deputy Chief of the INO, Mikhail Shpiegelglass, in charge of the Mobile Group that was to locate and liquidate Reiss and his family. Shpiegelglass was able to discover that Reiss had fled Belgium and was hiding in a village near Lausanne, Switzerland. Shpiegelglass enlisted the aid of a trusted Reiss family friend by the name of Gertrude Schildback, who was in the employ of the KGB, to lure Reiss to a rendezvous, where the Mobile Group riddled Reiss's body with machine-gun fire on the evening of 4 September 1937. His body was found by Swiss authorities on a road outside Lausanne.

Reiss's wife and daughter were spared, although it became clear that they had been intended to be victims of a box of chocolates that had been laced with strychnine poison. In her great haste to retreat from the scene of the crime, Schildbach had left behind her luggage at the small hotel where she was temporarily staying. During the course of their investigation, the Swiss police found the box of chocolates. Orlov speculated that Schildbach had neither the time nor the opportunity to give the chocolates to the intended victims, or, more probably, that she did not want to carry forth the murder plot. As a family friend, she had often played with the Reiss child and the bond that had developed with the child was more than likely the factor which caused her to renege on this part of the plot.

The other defector of note was Walter Krivitsky, who at the time of Reiss's demise had been the KGB illegal rezident in Holland. His defection would reach the highest levels of the French and Soviet Governments and almost became an international incident. Krivitsky had only been with the KGB since 1935, having previously worked for the Intelligence Administration of the Red Army. He was aware of Reiss's plan to defect and attempted to warn Reiss at his hideout in Switzerland when he learned that Shpiegelglass's Mobile Group had located him. Krivitsky was to learn of Reiss's fate on the morning of 5 September, when he read in a Paris newspaper the details of a macabre murder that had been discovered near Lausanne.

(2) John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, Deadly Illusions (1993)

The most senior NKVD officer to make a break was Ignace Reiss, who fled in July 1937 with his wife and child to Switzerland after receiving the fatal summons from Moscow. Before leaving his station he dropped off a letter at the Soviet embassy in Paris informing the Central Committee why he had broken with Stalin and announcing that he was "returning to freedom - back to Lenin, to his teachings and his cause". Stalin responded to this "in the eye" gesture of defiance by ordering Yezhov to wipe Reiss and his family off the face of the earth as an example to others. The "mobile group" of tvxvv assassins finally caught up with Reiss on 4 September in Switzerland, pumping him full of machine-gun bullets before dumping his body on a lonely roadside outside Geneva, near the village of Chamblades.

(3) Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009)

Zborowski regularly supplied Moscow with articles from the Bulletin of the Opposition before they appeared in print, and with copies of Trotsky's letters and manuscripts, including portions of his book-length indictment of Stalin, The Revolution Betrayed, which turned up on Stalin's desk before its publication in Paris in the summer of i937. That August came Zborowski's triumph, when Lyova went to the south of France and entrusted him with a small notebook containing the addresses of Trotskyists living outside the Soviet Union. "As you know, we have dreamed about getting hold of it for a whole year," an exultant Zborowski wrote to his superiors using his codename, Tulip, "but we never managed it before, because SONNY would never let it out of his hands. I enclose herewith a photo of these addresses."

During Lyova's absence from Paris, Zborowski stood in for him in negotiations to arrange a meeting with Ignace Reiss, the first of the GPU defectors. In making his break with the Kremlin, Reiss, the illegal resident in Belgium, had turned for help to the Dutchman Henk Sneevliet, a Communist member of parliament and trade union leader who had once been a close comrade of Trotsky's. Sneevliet, working through Zborowski, invited Lyova to meet Reiss on 6 September 1937 in Reims - which is where the defector might have met his end had a GPU mobile squad not machine-gunned him to death a day earlier on a rural road outside Lausanne.

When he read the news, Trotsky was incensed at Sneevliet. A GPU defector who could have drawn back the curtain on the Moscow trials had been murdered in obscurity. World-wide publicity, Trotsky argued, would have shielded Reiss from assassination. Instead, Sneevliet had acquiesced in Reiss's plan to delay any public announcement until after his impassioned letter of resignation reached the Central Committee in Moscow. Reiss was unaware that the staff member at the Soviet embassy in Paris to whom he had entrusted the posting of his letter had betrayed him, setting off a manhunt.

Trotsky saw deviousness, as well as ineptitude, in Sneevliet's handling of the Reiss affair. Sneevliet had not only failed to inform Trotsky in a timely way about the defection; he even appeared reluctant to bring Lyova into direct contact with Reiss. Yet while Sneevliet does give the impression of being the controlling sort, he also had the feeling that Lyova's comrades in Paris could not be trusted. And in the wake of Reiss's murder, Sneevliet's misgivings came to focus on Zborowski.

(4) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

A purge was made in the Fourth Department itself. Two Stalinists were brought into that department and Ignace Reiss suddenly realised that before long he, too, might well be next on the list for liquidation. He had been loyal to the Soviet Union, he had carried out all tasks assigned to him with efficiency and devotion, but, though not a Trotskyite, he was the friend of Trotskyites and opposed to the anti-Trotsky campaign. One by one he saw his friends compromised on some trumped-up charge, arrested and then either executed or allowed to disappear for ever.

When Reiss returned to Europe he must already have known that he had little choice in future: either he must defect to safety, or he must carry on working until he himself was liquidated. He had become known to the police and intelligence authorities of Britain, France, Austria, Holland and Germany, and latterly was one of the Resident Directors of Soviet espionage in France. When men with whom he had intimately been associated, such as Bukharin, Kamanev, Rakovsky and Zinovieff, had been executed or imprisoned, the writing was on the wall. In July 1937 he was warned that if he did not go back to Moscow at once he would be "treated as a traitor and punished accordingly".

It was then that Reiss courageously wrote his now celebrated letter to Stalin by which he signed his death warrant...It was, of course, a brave gesture, but it was also a feeble and inept one. There was no middle road for Ignace Reiss for the simple reason that Stalin had embraced Leninism and merely carried it to its logical conclusion in a totalitarian state. The gesture was empty because it led nowhere: Reiss did not disagree with the Communist revolution, only how Stalin had interpreted it, so he did not betray any secrets to the Western powers, nor did he seek political asylum. Instead he laid himself wide open to instant retribution from the N.K.V.D.

Stalin's rage was such that the finding and killing of Reiss was made a top priority and an elaborate and costly operation for assassinating Reiss was put in motion. The man given the task of planning this was Colonel Mikhail Shpiglglas, a commissar who had been engaged in making reports on the French network of Soviet espionage. He decreed that three special mobile commando units of Russian Intelligence should be detailed to seek out Reiss. The leaders of these three groups were Roland Abyatt, London-born former Resident Director in Prague, known under the alias of "Frangois Rossi", Vladimir Konradyev, a Soviet cultural attache in Paris, and Serge Efron, an agent who was sent to Paris under the cover of a Russian newspaperman.

Meanwhile Reiss, using a Czech passport in the name of Hans Erhardt, had disappeared to Switzerland, leaving his wife and child in Paris. Laboriously the Soviet man-hunt team went into action: Swiss agents were ordered to keep a look-out for Reiss, while others trailed his wife and child. It was not long before Elisabeth Poretsky was discovered travelling to Switzerland where she was tracked down to a hotel in Montreux.

It was at this stage that the Soviet Intelligence brought into action a Swiss teacher named Renata Steiner who had joined the Swiss Communist Party as a student and, following an Intourist visit to Russia in 1934, had been enrolled as a minor agent. Two years later she returned to Moscow and was given full-time work in Soviet Intelligence, being sent to join the French network in a cover job in an antique shop in Paris. The shop was used as a clearing-house for information.

Renata Steiner was employed with discretion; she was often given assignments without being allowed to know their true purpose. Thus, when she had been ordered to shadow a Monsieur and Madame Sedoff, she had no idea that M. Sedoff was the son of Trotsky, and that he had been marked down by Konradyev's organisation for assassination. Having shadowed the Sedoffs to Switzerland, she reported to her superiors that Ignace Reiss had contacted Sedoff. The discovery that Reiss was probably actively conspiring with Trotskyite circles caused the Soviet to redouble their efforts to locate and then liquidate him. Renata Steiner was assigned to Efron's organisation and succeeded in tracing Reiss to a village in the Alps. She was then ordered to trace Ignace's wife.

On 5 September 1937 a saloon car was noticed to be parked in the Boulevard de Chamblandes in Lausanne. Inside it was found the body of a man riddled with machine-gun bullets. In his pocket was the passport of "Hans Erhardt, of Prague". The Swiss police were baffled because they had no record of "Hans Erhardt". It was only when Ignace Reiss's widow called on them and said she was afraid the murdered man was her husband and formally identified the body that they realised a Soviet murder gang was operating in their midst.

It was then that Renata Steiner walked into a trap. She had been told to hire the car in which Reiss's body had been found and had paid the deposit on it. When she failed to trace Madame Poretsky and could not establish contact with her superiors she foolishly went to the garage to find out what had happened to the car she had ordered.

The Swiss police were waiting for her. Renata Steiner, not having read the papers, or learned of the murder of Reiss, could not at first understand why she was being interrogated. Even the Swiss police were quickly convinced that she was just a dupe of the killers and had no knowledge of the plan to murder Reiss. Nevertheless she was arrested, closely questioned, tried as an accomplice, receiving a sentence of only eight months' imprisonment.

Someone in Soviet Intelligence blundered badly in not ordering Renata Steiner to leave Switzerland and to stay out of the country the moment she had ordered the car from the garage. In fact there appeared to be conflicting orders, for Abyatt had instructed her to return to Paris at once, but another Soviet agent in Paris then told her to go back to Berne. When she was not contacted by her network she should have guessed something had gone wrong, but inexperience led her straight into a police trap.

Ignace Reiss had been liquidated, but at serious cost to at least two networks just because a vital witness had been allowed to fall into the hands of the police. Elisabeth Poretsky stated that "they left behind a witness who could identify them all and reveal the well-guarded secret that White Russian organisations were used in the services of the Soviet Union. The killers themselves got away."

None of them was ever caught, though intensive inquiries were made by the French police. But intelligence services of Europe were now alerted to the fact that many Russians calling themselves "White", anti-Bolshevik or pro-Czarist were now actively working for the Soviet Union. Either by blackmail, threats to relatives, or through sheer lack of money they had been ensnared not merely into the ranks of Soviet Intelligence but had been used as an expendable squad of killers of their fellow-countrymen, perhaps the basest form of treachery of all.

(5) Hede Massing, This Deception: KBG Targets America (1951)

We had spent many strenuous weeks with Helen (Elizabeth Zarubina) when toward the end of August we had a chance to go to Martha's Vineyard with some friends. We had been there not more than a few days when Helen called Paul Massing to come to New York. It was disturbing, but there was little else I could do but to let him go.

Two days passed. On the third day he returned and as I saw him standing on the ferry boat I knew that he had brought bad news. His face was tight, set, and he did not wave to me.

"Paul?" and before I could say another word - "Ludwig (Ignaz Reiss) is dead. He has been killed!"

He did not know any of the hideous details of Ludwig's death at the time. He had rushed back to me in fear that I might read about it in the papers. He wanted to be with me when that happened. It was a horrible shock.

We walked along the beach, through the sand dunes for hours and hours. We had lost Ludwig. "How do you know, Paul?" I asked. "Helen told me."

"What did she say? Who did it?"

He did not answer. He just looked at me. There was such a tragic sadness in his eyes that I stopped asking questions. He held me all night in his arms, as if to save me from the onslaught we felt inevitable. I could not get him to tell me of his conversation with Helen. Toward dawn he said, "Do you realize that Ludwig's death means immediate danger for us?"

We went early in the morning to Vineyard Haven, and from there to Edgartown to buy all the papers we could possibly find on the newsstands. But it was some time before the story broke.

The accounts were contradictory in minor details only; whether he had been killed by a submachine gun or an automatic pistol, whether he had five bullets in his head and seven in his body, or vice versa. But that he had fallen into a trap and been shot from behind was confirmed by all the papers in Switzerland and France.

The police investigation established the following facts:

On the night of September fourth, the body of an unknown man of about forty, riddled with machine gun bullets, was found on the road that led from Lausanne to the Chamblandes. There were fifteen bullets in his body. A strand of gray hair was clutched in the hand of the dead man. He was found by Max Davidson, a candy manufacturer. In his 'pocket was a passport in the name of Hans Eberhardt.

Police investigation checked his passport, which had been made out to a man born March 1, 1899, in Komotau, Czechoslovakia. It contained a French visa. He had registered as H. Eberhardt at the Hotel Continental as a businessman on a trip from Paris. The passport was forged.

On the theory that this was a political murder, they began checking their files and found that, in fact, the dead man was Ignace Reiss, thirty-nine, Polish born, former GPU agent, who had been attached to GPU outfits in Holland, Switzerland, Great Britain, and France - and in 1928 had been decorated by Stalin with the order of the Red Flag.

An abandoned American-made automobile in Geneva led to the identification of two mysterious guests, a man and a woman, who had registered on September 4th at the Hotel de la Paix in Lausanne, and had fled without their baggage and without paying their bill. The woman was Gertrude Schildbach, a German Communist, a resident of Rome. She was a GPU agent in Italy. The man was Roland Abbiat, alias Franqois Rossi, alias Py, a native of Monaco, and one of the Paris agents of the GPU.Among the effects left by Gertrude Schildbach at the hotel was a box of candy containing strychnine. Schildbach had been an intimate friend of the Reiss family, and frequently played with Reiss's child. She had lacked the force necessary to give this poisoned candy to his family, as she had been directed to do by Spiegelglass, the GPU agent in charge of the liquidation of Reiss.

Gertrude Schildbach had been wavering politically since the beginning of the purge, and she could plausibly play the part of one ready to join Reiss in breaking with Moscow. Reiss had known of her waverings and trusted her. He took her to dinner in a restaurant near Chamblandes to discuss the situation.

At this point, the papers differ. Some say that Reiss and Schildbach went for a little walk after dinner. They wandered off into an obscure road. A car appeared, came to a sudden stop. Several men jumped out and attacked Reiss. He fought the attacking band, but with the aid of Schildbach, whose strand of hair was found in his clutch, they forced him into the car. Here Abbiat-Rossi and Etienne Martignat, both Paris GPU agents, fired a submachine gun at Reiss. His body was thrown out of the car.

The other version was that two days after he was murdered, a car containing a blood-soaked overcoat was found in front of the Geneva-Cornavin railroad station. Police learned that the car had been rented by a young girl who was identified as Renate Steiner, twenty-nine, Swiss-born Sorbonne student, who worked for the GPU, shadowing persons under suspicion. She made a full confession.

She had trailed him through Holland, France, and Switzerland, finally locating him in Lausanne. She telephoned phoned Paris and they sent Gertrude Schildbach. While Reiss was dining with Schildbach, Renate Steiner appeared in the restaurant, accompanied by Vladimir Kondratieff, a White Russian and the killer of Reiss. Kondratieff was unemployed and a member of Eurasia, a Czarist society. This is the very same organization that sent out a certain M. Kovalev to catch Alexander Barmine, the Soviet diplomat, after he had fled the Russian service.

Steiner and Kondratieff suggested a drive after dinner in the car that the Steiner girl had hired. Reiss sat beside her, Schildbach and Kondratieff in the rear. Kondratieff killed Reiss during the drive and the trio dumped the body on the roadside where it was found.

Renate Steiner, who had been in the GPU service since 1935, and had previously shadowed Sedov, the son of Trotzky, was apprehended by the police, and confessed to her share of the crime. She helped the authorities to solve it.

That is the story of Ludwig's death, as we learned it from the newspapers.

When Paul and I regained our composure enough to be able to talk about it, we could not stop wondering how so extremely clever and careful a man could have fallen into such a trap. The very man who had taken such pains to introduce me to the principals of conspiracy, of checking and re-checking before any action, any meeting, anything! The man who cautioned Paul time and again to be careful in trusting any of the Nazis who professed sympathies with us; never to go to an appointment with anybody without safety measures, meaning with one or two body guards. How could he have gone alone to this meeting with Schildbach?!

"He probably had no one to go with him," Paul thought.

"But why did he go at all?" I asked.

"He had to go. He thought that this woman needed help to make up her mind one way or the other; and he felt that she was his responsibility. As a security measure he did not take his wife, Else, along and he probably had no one else to go with."

After a while, Paul said, "Once you leave the fold, you are quite alone. From the one-time Chief of the ! whole Western Intelligence Service in Europe it was but a quick transformation to a lonely man, killed by a 'friend' in a car and thrown out on a road-like a leper! After a life of devoted revolutionary service! A life of danger and sacrifice.