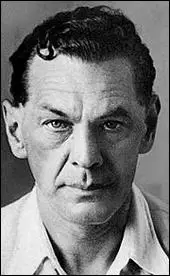

Richard Sorge

Richard Sorge, the son of Gustav Sorge, a German mining engineer, and the youngest of nine children, was born in Baku, Russia, on 4th October, 1895. His father was employed by the Caucasian Oil Company. His mother was Russian. In 1898 the Sorge family moved to Germany. (1)

Gustav Sorge had a senior position with a Berlin bank and the family settled in a comfortable middle-class neighbourhood. Richard later recalled: "My childhood was passed amid the comparative calm common to the well-off bourgeoisie in Germany. Economic worries had no place in our home." He was a rebel at school: "I was a bad pupil, defied the school's regulations, was obstinate and wilful and rarely opened my mouth." However some subjects did appeal to Sorge: "In history, literature, philosophy, political science... I was far above the rest of the class." (2)

On the outbreak of the First World War Sorge joined the German Army. In June 1915 Sorge's unit was transferred to the Eastern Front. He was a courageous soldier and was awarded the Iron Cross. In March 1916 Sorge was badly wounded when both legs were broken by shrapnel. While in hospital he began a relationship with one of his nurses. Over the next few months he met and was influenced by the woman's Marxist father. Not fit enough to return to the frontline, Sorge was allowed to study at Berlin University and Kiel University before studying for a PhD at Hamburg University. (3)

Richard Sorge later recalled that he now "decided not only to study, but also to take part in the organized revolutionary movement". His experiences during the First World War had radicalised Sorge and during the German Revolution he joined the left-wing group, the Spartacus League. Most of the leaders of the revolution, including Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Leo Jogiches were executed but Sorge survived. (4)

Richard Sorge & the German Communist Party

Sorge was proud of the fact that his great-uncle, Friedrich Sorge, was one of the most important radical socialists in the 19th century. At a meeting on 28th September, 1864, Sorge had joined together with Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Lassalle, William Greene, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui to form the International Workingmen's Association. (5)

A natural linguist, Sorge became fluent in German, Russian, English, French, Japanese and Chinese. However, in 1920, in an attempt to learn more about the workers, he became a coal miner. In 1922 he undertook occasional work as a teacher and a journalist. He began an affair with Christiane Gerlach, the wife of Kurt Albert Gerlach, one of his former professors. She later recalled: "It was as if a stroke of lightning ran through me. In this one second something awoke in me that had slumbered until now, something dangerous, dark, inescapable.” After the death of Gerlach on 19th October, 1922, from diabetes, Christiane married Sorge. (6)

Sorge and his wife associated with a group of revolutionaries that included Hede Massing, Gerhart Eisler, Georg Lukács and Julian Gumperz. Massing later wrote: "Their apartment was the center of the social life of this group, I remember how old-fashioned everything was, with the antique furniture that Christiane made of her past as the wife of a rich bourgeois. There was a fine collection of modern paintings and rare old engravings, I was impressed by the ease with which life played in the house, and I liked the mix of earnest conversation and joie de vivre. They developed more sensitivity and taste than was customary in German Communist circles." (7)

Alexander Ludwig, Konstantin Zetkin, Georg Lukács, Julian Gumperz,

Richard Sorge, Karl Alexander (child), Felix Weil, unknown; sitting: Karl August

Wittfogel, Rose Wittfogel, unknown, Christiane Sorge, Karl Korsch, Hedda Korsch,

Käthe Weil, Margarete Lissauer, Bela Fogarasi, Gertrud Alexander (1922)

Sorge's devotion to the Communist cause and his intellectual abilities, soon attracted the attention of the Soviet Intelligence. In 1925 he was recruited as a spy for the Soviet Union. He resigned as a member of the German Communist Party (KPD) and became an agent of the Comintern Intelligence Division. Sorge was trained by Nikolai Yablin, who had been born in Bulgaria who had emigrated to the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution. (8)

Ruth Fischer, a member of the KPD, was surprised how quickly he appeared to reject his previously held Marxist beliefs: "He showed strangely little interest in Marxist theory and devoted his attention from the outset to contemporary politics. He surprised his Marxist comrades by his great interest in Nazism, fascism, and anti-Semitism, and established an archive of these branches and soon became one of the best-informed experts on Nazism, at that time a minor power in Germany." (9)

Government Political Administration (GPU)

In 1927 Richard Sorge, using the cover of being a German freelance journalist, was sent to Los Angeles to make a detailed report on the Hollywood film industry. The following year he visited Britain to "study the labour movements, the status of the Communist Party and the political and economic conditions in Britain." While he was in London he was spotted by MI5 as a former member of the KPD and was asked to leave the country. (10) According to one report Sorge worked "with the local communist parties on the collection, exploitation, and transmission of information on workers' problems and communist initiative, and in part appear to have been tasked with advising and encouraging local communist organizations." (11)

In November 1929, Sorge was instructed by the the Government Political Administration (GPU) to join the Nazi Party and to break off contact with his left-wing friends. Elsa Poretsky, the wife of Ignace Reiss, a fellow agent in the GPU, commented: "His joining the Nazi Party in his own country, where he had a well documented police record was hazardous, to say the least... his staying in the very lion's den in Berlin, while his application for membership was being processed, was indeed flirting with death. Such actions were typical of... his superb self-assurance." (12)

It seems Sorge convinced people that he was indeed a fascist. A Japanese journalist claimed he was a "typical, swashbuckling, arrogant Nazi... quick-tempered, hard-drinking". As fellow agent, Hede Massing, pointed out: "He (Sorge) read voluminously any and all things he could find, to be prepared for discussion of the Nazi doctrine. He had familiarized himself with the phrases and sentiments. He had practically memorized Hitler's Mein Kampf." (13)

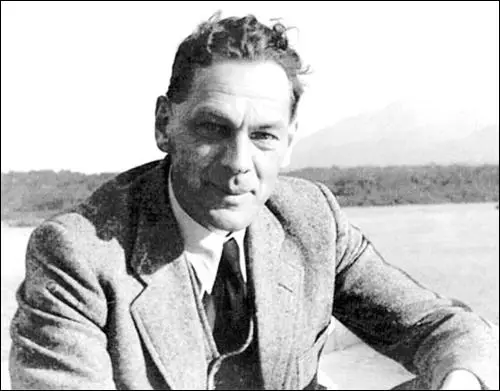

To help develop a cover for his spying activities Richard Sorge obtained a post working for the newspaper, Getreide Zeitung. In 1930 Sorge moved to China and made contact with another spy, Max Klausen. Sorge also met Agnes Smedley, the well-known left-wing journalist. She introduced Sorge to Ozaki Hotsumi, who was employed by the Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun. Later Hotsumi agreed to join Sorge's spy network. (14)

It was claimed that Sorge had a sexual relationship with Smedley. However, he once said: "Smedley had a good educational background and a brilliant mind, but as a wife her value was nil. In short, she was like a man. I might add that cultivation of intimate relations with married women for purposes of espionage will arouse the jealously of their husbands and hence react to the detriment of the cause." (15)

In 1933 Sorge married Katya Maximova, a young drama student who he had met in Moscow. According to William Boyd: "Shanghai suited Sorge. He was a committed communist but it didn’t stop him from living life to the full. A near-alcoholic and compulsive womaniser (even though he now had a wife, Katya, back in Moscow), he also had a passion for speed that manifested itself in the shape of powerful motorbikes. His preferred method of seduction was to take the woman he fancied on a terrifying bike ride through the streets of Shanghai before he pounced." (16)

Elsa Poretsky later recalled that Sorge had a terrible reputation with women while serving overseas. She claimed that Sorge believed that his wife had been recruited by the GPU and was spying on him. Christiane Sorge was now a school-teacher living in the United States: "Christiane, a distinguished-looking, reddish-blonde German girl whom Sorge met when they were both at university. It was said that he persuaded her to leave her professor husband and run away with him." (17) One of his fellow agents described him as "startlingly good-looking... romantic, idealistic" who exuded charm. (18) Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, and an intelligence officer, described Sorge as “the most formidable spy in history.” (19)

Great Illegals

In 1933, Artur Artuzov, the head of GPU decided to get Sorge to organize a spy network in Japan. He was asked to visit Moscow and was given his instructions by Yan Berzin: "We want you to take up residence in Japan. Rapprochement between Germany and Japan is coming; in Tokyo, you will learn a great deal about military preparations... Our objective is for you to create a group in Japan determined to fight for peace. Your work will be to recruit important Japanese, and you will do everything in your power to see that their country is not dragged into the war against the Soviet Union." (20)

As cover Sorge returned to Nazi Germany where he was able to get commissions from two newspapers, the Börsen Zeitung and the Tägliche Rundschau. He also got support from the Nazi theoretical journal, Geopolitik. Later he was employed by the Frankfurter Zeitung. Sorge arrived in Japan in September 1933. He was warned by his spymaster not to have contact with the underground Japanese Communist Party or with the Soviet Embassy in Tokyo. His spy network in Japan include Max Klausen, Ozaki Hotsumi, and two other Comintern agents, Branko Vukelic, a journalist working for the French magazine, Vu, and a Japanese journalist, Yotoku Miyagi, who was employed by an English-language newspaper. (21)

It has been argued by Oliver Bullough that "Sorge was part of a generation of committed communists who took lunatic risks to help Stalin understand the threat from the Axis powers. They were rewarded by being belittled, ridiculed and smeared... This highlights the contrast between the lofty professed ideals of the Soviet Union and its squalid reality, along with the sad fates of those people unwise enough to trust the communist state with their lives. Stalin didn’t deserve Sorge, and these poor women deserved far better than Sorge too." (22)

Sorge was a member of a group of Soviet agents that became known as the "Great Illegals" who agreed with Leon Trotsky on the subject of world revolution. This is why they were willing to work undercover in the countries hostile to the Soviet Union in an effort to ferment revolution. This group included Arnold Deutsch, Walter Krivitsky, Theodore Maly, Ignace Reiss, Leopard Trepper, Alexander Orlov, Artur Artuzov, Yan Berzin, Boris Vinogradov, Peter Gutzeit, Boris Bazarov, Dmitri Bystrolyotov and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko. By the summer of 1937, Stalin became convinced that these agents were conspiring against him and over forty of them serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Deutsch, Maly, Berzin, Artuzov, Vinogradov, Gutzeit, Bazarov and Antonov-Ovseenko were all executed. Reiss and Krivitsky refused to return and were murdered abroad. (23)

As Peter Wright, the author of Spycatcher (1987), who worked for British intelligence, pointed out: "They were Trotskyist Communists who believed in international Communism and the Comintern. They worked undercover, often at great personal risk, and traveled throughout the world in search of potential recruits. They were the best recruiters and controllers the Russian Intelligence Service ever had. They all knew each other, and between them they recruited and built high-grade spy rings like the Cambridge Five in Britain, Sorge's rings in China and Japan, the Rote Drei in Switzerland and the Rote Kapelle in German-occupied Europe - the finest espionage rings history has ever known, and which contributed enormously to Russian survival and success in World War II." (24)

Although it is clear that Stalin never trusted Sorge and considered him a Trotskyist, he was persuaded by senior members of the NKVD that he was such a valuable agent he should be allowed to stay in place. (25) Leopold Trepper has argued: "They realized... that Sorge could not be replaced, and in the end, they left him in Tokyo. From then on Sorge was suspected at the Center of being a double agent and - crime of crimes - a Trotskyite. His dispatches would go for weeks without being decoded." (26)

As Oliver Bullough has pointed out: "Tokyo was a very different prospect to Shanghai, with few foreigners and a suspicious government, so spying would require a high degree of mastery. Sorge, however, set to work with a will. He put together a network that penetrated into the very heart of the Japanese administration and was able to produce crucial information on the country’s intentions, resources and abilities. He dived into the German community, sleeping with its women, drinking with its men, and establishing a reputation as the best-informed foreign observer of Japanese politics." (27)

A fellow Soviet spy, Hede Massing, saw Sorge again when he made a visit to New York City in 1935: "Sorge, whom we had originally known as a calm, scholarly man, had changed visibly in the few years he had been working for the Soviet Union. When I saw him for the last time in New York in 1935 he had become a violent man, a strong drinker. Little was left of the charm of the romantic, idealist student, although he was still extraordinarily good-looking. But his cold blue, slightly slanting eyes, with their heavy eyebrows, had retained their capacity for self-mockery, even when this was groundless. His hair was still brown and unthinned, but his cheekbones and sad mouth were sunken, and his nose was pointed. He had changed completely." (28)

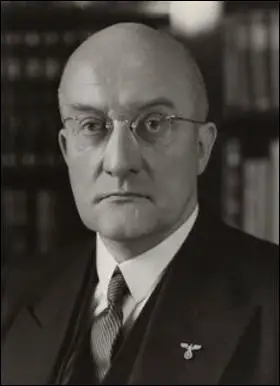

Sorge was successful at appearing to be a passionate supporter of the Nazi Party. This helped him develop good relations with several important figures working at the German Embassy in Tokyo. This included Eugen Ott and the German Ambassador Herbert von Dirksen. This enabled him to find out information about Germany's intentions towards the Soviet Union. Other spies in the network had access to senior politicians in Japan including prime minister Fumimaro Konoye and they were able to obtain secret details of Japan's foreign policy. (29)

Sorge always maintained that his job as a writer for newspapers and magazines helped him enormously in his quest for intelligence. "A shrewd spy will not spend all his time on the collection of military and political secrets and classified documents. Also, I may add, reliable information cannot be procured by effort alone; espionage work entails the accumulation of information, often fragmentary, covering a broad field, and the drawing of conclusions based thereon. This means that a spy in Japan, for example, must study Japanese history and the racial characteristics of the people and orient himself thoroughly on Japan's politics, society, economics and culture." (30) Such was his success Sorge has been described as "among the greatest spies of the century." (31)

In 1938 Eugen Ott replaced Herbert von Dirksen as ambassador. Ott, by now aware that Sorge was sleeping with his wife, let his friend Sorge have "free run of the embassy night and day" as one German diplomat later recalled. As the New York Times pointed out: "Sorge won the confidence of the German military attaché, Eugen Ott, who upon assuming the ambassadorship in 1938 made Sorge press attaché and informal adviser. The head of the Gestapo's intelligence network in the Far East also maintained a close relationship with Sorge, who was regarded as a devoted Nazi." (32)

Richard Sorge met Hanako Miyake, a twenty-five year old bar girl, on his fortieth birthday. "Since it was Hanako's turn to serve, she went over to take the blue-eyed foreigner's order. He turned his bright smile on the waitress, and examined her with evident interest. The girl Sorge saw was not a beauty in the conventional sense. Plumpish, with a dimpled moon face and soft babyish features, she gave a bashful impression that was only partly contrived." Sorge took her out the following day and it was not long before she was his mistress. (33)

Each morning Sorge would regale Ambassador Ott with gossip and information about Japanese affairs and in return the latter would tell him all manner of things about his own relations with the Japanese. Sorge warned Moscow that Germany was turning from her traditional friendship towards China in favour of an alliance with Japan. This posed a danger to the Soviet Union on two fronts, the east and the west. Sorge warned that Japan would attack wherever the great powers were weakest and the Soviet Union needed to build up her defences in the east. Sorge also forecast that sooner or later Japan would strike a blow against the British Empire. "Singapore," reported Sorge, "is a symbol of British unpreparedness. It is not a citadel, but an open invitation to an adventurous invader and can be taken with comparatively small casualties in less than three days." (34)

In 1939 Leopold Trepper, an agent for the NKVD, established the Red Orchestra network and organised underground operations in several countries. Richard Sorge was one of its key agents. Others in the group included Ursula Beurton, Harro Schulze-Boysen, Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Arvid Harnack, Mildred Harnack, Sandor Rado, Adam Kuckhoff and Greta Kuckhoff. Arvid Harnack, who worked in the Ministry of Economics, had access to information about Hitler's war plans, and became an important spy. Harnack had a close relationship with Donald Heath, the First Secretary at the US Embassy in Berlin. (35) According to Viktor Mayevsky, in the spring of 1939, Sorge told Moscow that Germany would invade Poland on 1st September, 1939. (36)

Operation Barbarossa

On 18th December, 1940, Adolf Hitler signed Directive Number 21, better known as Operation Barbarossa. It included the following: "The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign even before the conclusion of the war against England. For this purpose the Army will have to employ all available units, with the reservation that the occupied territories must be secured against surprises. For the Luftwaffe it will be a matter of releasing such strong forces for the eastern campaign in support of the Army that a quick completion of the ground operations can be counted on and that damage to eastern German territory by enemy air attacks will be as slight as possible. This concentration of the main effort in the East is limited by the requirement that the entire combat and armament area dominated by us must remain adequately protected against enemy air attacks and that the offensive operations against England, particularly against her supply lines, must not be permitted to break down. The main effort of the Navy will remain unequivocally directed against England even during an eastern campaign. I shall order the concentration against Soviet Russia possibly 8 weeks before the intended beginning of operations. Preparations requiring more time to get under way are to be started now - if this has not yet been done - and are to be completed by May 15, 1941." (37)

Within days Richard Sorge had sent a copy of this directive to the NKVD headquarters. Over the next few weeks the NKVD received updates on German preparations. At the beginning of 1941, Harro Schulze-Boysen, sent the NKVD precise information on the operation being planned, including bombing targets and the number of troops involved. In early May, 1941, Leopold Trepper gave the revised date of 21st June for the start of the Operation Barbarossa. On 12th May, Sorge warned Moscow that 150 German divisions were massed along the frontier. Three days later Sorge and Schulze-Boysen confirmed that 21st June would be the date of the invasion of the Soviet Union. (38)

In early June, 1941, Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, the German ambassador, held a meeting in Moscow with Vladimir Dekanozov, the Soviet ambassador in Berlin, and warned him that Hitler was planning to give orders to invade the Soviet Union. Dekanozov, astonished at such a revelation, immediately suspected a trick. When Stalin was told the news he told the Politburo it was all part of a plot by Winston Churchill to start a war between the Soviet Union and Germany: "Disinformation has now reached ambassadorial level!" (39)

On 16th June, 1941, an agent cabled NKVD headquarters that intelligence from the networks indicated that "all of the military training by Germany in preparation for its attack on the Soviet Union is complete, and the strike may be expected at any time.". Later Soviet historians counted over a hundred intelligence warnings of preparations for the German attack forwarded to Stalin between 1st January and 21st June. Many of these were from Sorge but by this time Stalin was convinced that he was a double-agent and working on behalf of Britain. Stalin's response to an NKVD report from Schulze-Boysen was "this is not from a source but a disinformer." (40)

On 21st June, 1941, a German sergeant deserted to the Soviet forces. He informed them that the German Army would attack at dawn the following morning. War Commissar Marshal Semyon Timoshenko and Chief of Staff General Georgy Zhukov, went to see Stalin with the news. Stalin reaction was the alleged German deserter was an attempt to provoke the Soviet Union. Stalin did agree to send out a message to all his military commanders: "There has arisen the possibility of a sudden German attack on June 21-22... The German attack may begin with provocations... It is ordered to occupy secretly the strong points on the frontier... to disperse and camouflage planes at special airfields... to have all units battle ready... No other measures are to be employed without special orders." (41)

Stalin now went to bed. At 3.30 a.m. Timoshenko received reports of heavy shelling along the Soviet-German frontier. Timoshenko told Zhukov to call Stalin by telephone: "Like a schoolboy rejecting proof of simple arithmetic, Stalin disbelieved his ears. Breathing heavily, he grunted to Zhukov that no counter-measures should be taken... Stalin's only concession to Zhukov was to rise from his bed and return to Moscow by limousine. There he met Zhukov and Timoshenko along with Molotov, Beria, Voroshilov and Lev Mekhlis.... Pale and bewildered, he sat with them at the table clutching an empty pipe for comfort. He could not accept he was wrong about Hitler. He muttered that the outbreak of hostilities must have originated in a conspiracy within the Wehrmacht... Hitler surely doesn't know about it. He ordered Molotov to get in touch with Ambassador Schulenburg to clarify the situation." (42)

Joseph Stalin was too shocked and embarrassed to tell the people of the Soviet Union that the country had been invaded by Germany. Vyacheslav Molotov was therefore asked to make the radio broadcast. "Today at four o'clock in the morning, German troops attacked our country without making any claims on the Soviet Union and without any declaration of war... Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. We will be victorious." (43)

Pearl Harbour

In the autumn of 1941, Sorge and his comrades provided Stalin with the information that the Japanese were preparing to make war in the Pacific and were concentrating their main forces in that area in the belief that the Germans would defeat the Red Army. (44) According to Pravda, Sorge informed Soviet intelligence two months before Pearl Harbour "that the Japanese were getting ready for a war in the Pacific and would not attack the Soviet Far East, as the Russians feared." (45)

The Japanese became convinced there was a spy inside the German Embassy. They also discovered that an illegal radio transmitter was being used by the Russians in Tokyo. In October, 1941, the Japanese police arrested Yotoku Miyagi, one of the key figures in Sorge's network. He attempted suicide by leaping head-first from an upper-storey window of the police station, but shrubbery broke his fall. Under torture he confessed, and gave the name of Sorge and his associates. (46)

Sorge was placed under surveillance and it was arranged for him to have an affair with Kiyomi, a spy working for the Japanese secret service. One night they were in a restaurant together she noticed the waiter drop a tiny ball of rice paper on the table they were sharing. Sorge picked it up and learned that he was in danger of being arrested and was urged to escape immediately. When he was in the car, Sorge attempted to set fire to the piece of paper. When the lighter failed him he asked Kiyomi for a light, but she pretended she could not give him one. Exasperated, he threw the rice paper out of the window and drove off. Kiyomi asked Sorge to stop the car so that she could warn her parents that she was staying out for the night. He agreed and she rang up the secret police and told them exactly where the paper had been dropped. It was immediately recovered and Sorge was arrested. (47)

Ambassador Eugen Ott was outraged when he heard that Sorge had been arrested "on suspicion of espionage" and thought it was a "typical case of Japanese espionage hysteria". He told people around him "Sorge a spy? What twaddle! I would put my hand in the fire for the man." Heinrich Loy, a German working in Tokyo, also found it difficult to believe: "I've known Sorge personally for a long time, but this news surprised me and made me realise he was different from other people. Normally people you've known a long time will make a careless slip on some occasion. Particularly when someone drinks like a fish, as Sorge did, you expect that he will reveal his true self. Considering that he managed to conceal his identity up until now, I have to say he was an exceptional man." (48)

Japan and the Soviet Union were not at war at the time. General Tominaga, Vice-Minister of Defence, later told Leopold Trepper that: "Three times we proposed to the Soviet Embassy in Tokyo that Sorge be exchanged for a Japanese prisoner. Three times we got the same answer: The man called Richard Sorge is unknown to us." Trepper suggested that Stalin had no desire to see Sorge returned. "Richard Sorge paid for his intimacy with General Berzin. After Berzin was eliminated, Sorge, in the eyes of Moscow, was nothing but a double agent, and a Trotskyite in the bargain!" (49)

Stalin even had Sorge's wife, Katya Maximova, arrested by the NKVD on the charges that she was a "German spy", and was deported to the Gulag where she died in 1943. Hanako Miyake visited Sorge while he was in prison. According to Miyake, Sorge eventually struck a deal with the Kempeitai that if they would spare his mistress and the wives of the other members of the spy ring, he would reveal all. (50)

Richard Sorge was executed by the Japanese on 7th November 1944 his last words were: “The Red Army!”, “The International Communist Party!” and “The Soviet Communist Party!”, all delivered in fluent Japanese to his captors. "Sorge was bound hand and foot, the noose already set around his neck. Tall, blue-eyed, ruggedly good-looking and apparently unperturbed by his imminent demise, Sorge was contributing the perfect denouement to what he might well have assumed was an enduring myth in the making." (51)

In 1961, Yves Ciampi, wrote and directed Who Are You, Mr. Sorge? about the life of Sorge. When the French film was shown in Moscow, Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader saw it. He asked the Committee for State Security (KGB) to investigate the story. When they reported that the intelligence files suggested the story was true he encouraged one of the Soviet's top journalists, Viktor Mayevsky, to carry out further research into Sorge. (52)

The article eventually appeared in Pravda: "Richard Sorge is a man whose name will become the symbol of devotion to the great cause of the fight for peace, the symbol of courage and heroism... The struggle against fascism, against a second world war became the purpose of Sorge's life.... In April, 1941, Richard Sorge supplied valuable information about the preparation of a Hitlerite attack on the Soviet Union... He said 150 divisions were being concentrated at the borders of the U.S.S.R., supplied a general scheme of the military operations and in some reports, at first by one day off but later exactly, named the date of the attack, June 22.... But Stalin disregarded it. How many thousands and millions of lives would have been saved had the information from Richard Sorge and others not been sealed up in a safe! " (53)

On 5th November, 1964, 20 years after his death, the Soviet government awarded Sorge the title "Hero of the Soviet Union". Sorge's mistress Hanako Miyake, was still alive and she was granted a pension by the Soviet government. This was paid until her death in July 2000. (54)

Primary Sources

(1) William Boyd, New Statesman (6th March, 2019)

Born in 1895 to a German father and a Russian mother in Baku, an oil town on the Caspian Sea, Sorge had a comparatively settled bourgeois upbringing, particularly after the family moved back to Berlin when he was a young child.

What radicalised him was the First World War. He enlisted as a soldier when hostilities began and he saw a lot of action, being wounded three times. The slaughter he witnessed on the Western and Eastern fronts made Sorge embrace communism. In the near-civil war that erupted in Germany after the Armistice he joined the Spartacist revolutionaries who saw the future of Germany as a utopian workers’ republic.

Sorge’s activities were significant enough to draw the attention of the embryonic Soviet regime’s secret services, the so-called Fourth Department, a forerunner of the NKVD and the KGB. Sorge became an agent of the Comintern, the international wing of the Communist Party, and was sent briefly to Britain and then Berlin, where his diligence and zeal were duly noted. In the 1920s the Fourth Department developed its system of “rezidents”, illegal spy centres in key cities, as opposed to the “legals” who were usually working under the guise of diplomatic immunity. Sorge was sent to Shanghai in 1930 to join the apparat being established there and thus began an association with the Orient that was to endure for the rest of his life as a spy.

(2) Richard Sorge later wrote about his experiences of the First World War.

None of my simple soldier friends knew the real purpose of the war, not to speak of its deep-seated significance. Most of the soldiers were middle-aged men, workers and craftsmen by profession. Almost all of them belonged to industrial unions, and many were Social Democrats. There was one real leftist, an old stonemason from Hamburg, who refused to talk to anybody about his political beliefs. We became firm friends, and he told me of his life in Hamburg and of the persecution and unemployment he had gone through. He was the first pacifist I had come across. He died in action in the early days of 1915, just before I was wounded for the first time.

(3) Document produced by the Japanese police after interrogating Richard Sorge in 1941.

The accused, Richard Sorge, after experiencing the horrors of the last war, came to the realization that certain self-evident contradictions are inherent in the capitalist system of the present day, joined the workers' movement towards the end of the war, studied Communist literature and gradually became a believer in Communism. He was admitted to membership of the German Communist Party in November 1919 in Hamburg, and here and elsewhere engaged in clandestine propaganda, agitation and educational work. When, in January 1925, he attended a congress convened in Moscow by Comintern Headquarters in the capacity of a delegate of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party Central Secretariat, he received instructions to join the Comintern Information Department and to continue his work under its aegis. In the spring of 1930, having received instructions to concentrate on espionage, he went to China and carried out his assignment in various localities. On receiving further instructions to carry out parallel activities in Japan, he applied in Berlin for membership of the German National Socialist Party. By way of camouflage, he simultaneously took up the post of correspondent of the Frankfurter Zeitung.

(4) Agnes Smedley met Richard Sorge in China in 1930. She wrote about their relationship in a letter to Florence Lennon in May 1930.

I'm married, child, so to speak - just sort of married, you know; but he's a he-man also, and its 50-50 all along the line, with he helping me and I him and we working together or bust, and so on; it's a big, broad, all-sided friendship and comradeship. I do not know how long it will last; that does not depend on us. I fear not long. But these days will be the best in my life. Never have I known such good days, never have I known such a healthy life, mentally, physically, psychically.

(5) Der Spiegel (13th June 1951)

Do you even know how the Japanese execute their prisoners? Slowly, bit by bit, tighten the wire loop so that you can wriggle properly. They do not hang up, strangle them. Such fine people are that, our Japanese! He was right: a small but bad people. Cheers!"

The man, still sipping the whiskey of freedom, made this statement on October 7, 1944, had occasion to revise his harsh opinion by personal experience. At 1020, the bottom of the jail in Tokyo's "Sugamo" prison opened beneath him. At 10.36 he was already pronounced dead. His last words were addressed to the prison officials: "Thank you for all your kindness." "Firm step," notes the Japanese report, had gone to the trapdoor under the noose. This October 7th was the 27th anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

Japanese government officials later reported that the delinquent had clenched his fist in German language high on the Soviet Union. Later they recanted: they were not present at the execution....

After the massacres of Minsk and Orel, the Russians were extremely worried that the Japanese would be able to annul the non-aggression pact they had just completed and bring the beleagured Red troops into the Siberian flank. In August 41, concern reported that Japan's fleet had oil for two years, the army for half a year.

Then, on 15 October, he gave the decisive slogan: Japan had decided to attack south against the Anglo-Saxons, with a raid of the Kwantung Army in Siberia is no longer to be expected. Three days later, Sorge and his closest associates were arrested. Of the 35 people arrested in connection with concern, 18 were later found innocent.

At one stroke, the Japanese solved the mystery of unexplained radio messages that they had been after for six years. They had never been able to detect the transmitter by radio bearings, since Sorges radio operator Max Klausen changed the location each time and since he preferred to send in a fishing boat from the sea. In 1939, according to Klaus's diary, these were 23,139 phrases, and in 1940 29,179 phrases.

The group received money from the Soviets through Klaus's business account. When the transfers became too risky, Klausen asked the Soviet Consul for a liaison office in Tokyo. In many cases, the money was then paid out progressively against microfilm rolls, which were transported in the voluminous bosom of Mrs. Klausen. Once a year, concern raised revenue and expenses and microfilmed to Moscow. Neither sparks nor microfilms nor money transfers led to the discovery of the group concern. Rather, she came to the police on the display of a man under the knife, who until recently was one of the six leading Communists of Japan.

The former private secretary of the willing-to-compromise Prime Minister Prince Konoye, who stepped down two days before Sorges was arrested and gave way to the War Cabinet Tojo, was arrested with concern (and the only one later hanged). The German Ambassador to Tokyo, Eugen Ott, was quite suspicious of MacArthur's file, claiming that Sorge had lived with him "on familiar terms." Concern was for a while a permanent guest of the ambassador, had access to the cipher room and worked completely unattended in the rooms of the embassy to put together the "German Service", an unofficial news bulletin...

"Briefly," summed up the MacArthur report, "Sorge was able to inform the Soviet Union comprehensively about the military, political, and industrial intentions of the Japanese from 1933 to 1941. The Red Army has always known the status of their respective Japanese plans and plans could make their own plans and decisions afterwards.

"It is surprising that the Japanese, despite their ingrained suspicions of foreigners, despite their vigilance against the slightest signs of espionage and Communist sympathies, despite their accuracy, with which they forced couriers to pass their country through well-guarded ports, not the slightest Distrust of concern and the people of his group. "

"I would like to say," concern says in his confession, "that my news work in China and Japan was completely new and first-time, especially in Japan, where I am the first and only one who has ever been able to do such a thing to fulfill this task for so long and successfully."Sorge did not work under pressure like Colonel Redl, and certainly not for money. Nor is he the prototype of the Communist agent whom the MacArthur report sees in him. The pleasure of sailing under your own flag has never been taken care of. But he believed in the global future of the Soviet state and maintained the pacifist and man-sentimental resentments of the doctrinaire Marxist throughout his life. He devoted himself to the Russian military intelligence service for the very big game, because only here he sensed the freedom of the adventure he needed to live...

In 1898, Father Sorge returned to Germany, but remained a buyer of Russian society until 1906. He lived in Hildesheim for a long time, hoping that he would be able to get into the oil wells in the Lüneburg Heath, and in Koblenz, from 1911 to 1912 in Munich. The warm-hearted mother sincerely regretted her boarding-school sprouts. In 1912, the Sorge family moved to Berlin-Lankwitz. Richard himself became a Berliner ten years earlier. In the self-signed CV of his doctoral files it says:

"When I was 6 years old, I went to the upper secondary school in Berlin-Lichterfelde, after my parents had moved from Russia during my third year of life.I attended the Lichterfelder Oberrealschule without interruption until the outbreak of the war, during which I immediately called for military service and campaigned as a volunteer to Belgium in October 1914. A wound suffered in 1915 enabled me to catch up with my high school graduation exam and enroll at the University of Berlin.

After further wounds that allowed me to visit the university, I left Berlin in the spring of 1918 and moved to the University of Kiel, where I enrolled in the faculty of political science." After having written my dissertation in Kiel, I went to the University of Kiel Spring 1919 to Hamburg, to arrive at the establishment of the local university at this conclusion of my studies."

Julian Gumperz read in Berlin the still unpublished script of the American student Agnes Smedley, who studied in Berlin in 1927/28. He translated it for the "Frankfurter Zeitung", where it came out under the title "A Woman Alone". It was her own biography. Her mother was a farmer's daughter, but she had to go as a laundress, while the drunken father beat the family Agnes stole for her younger siblings. She became a student student and joined the ranks of the Indian Revolutionary Movement during the First World War, where she learned to hate colonial methods (and the English). She herself has Indian and Jewish blood as well as Quaker ancestors. In her fight against oppression, she became obsessed by the idea that love was the woman's enemy.

Sorge said in Frankfurt about her: "This is a very splendid woman who stirs up the sons and daughters of the Frankfurt capitalists who are diligently dissuaded by communism." Yes, she is capable of frightening the social conscience of an already philanthropic manufacturer: logical-mathematical, systematic it is a zero, but one that increases a given digit to ten times its value. "

The Smedley came in 1928 to the conclusion of "One Woman Alone" to Frankfurt. The "Frankfurter Zeitung" engaged her as Far East correspondent. The sinologist Richard Wilhelm, who had previously represented the "Frankfurter Zeitung", wanted to go home to Frankfurt. He became head of the German-Chinese Society, on whose behalf concern should go to China, and if it is true that the Smedley was an agent, then he has indirectly helped two Soviet spies to China.

(6) Hede Massing quoted in Der Spiegel (27th June 1951)

Sorge, whom we had originally known as a calm, scholarly man, had changed visibly in the few years he had been working for the Soviet Union. When I saw him for the last time in New York in 1935 he had become a violent man, a strong drinker. Little was left of the charm of the romantic, idealist student, although he was still extraordinarily good-looking. But his cold blue, slightly slanting eyes, with their heavy eyebrows, had retained their capacity for self-mockery, even when this was groundless. His hair was still brown and unthinned, but his cheekbones and sad mouth were sunken, and his nose was pointed. He had changed completely.

(7) Document produced by the Japanese police after interrogating Richard Sorge in October 1941.

In September 1933 Sorge arrived in Japan from America in this capacity. From that time until his arrest he concealed his illegal activities by posing as a Yugoslav national, Vukelic, of Japanese citizens and of other foreigners; amassed information (again in collaboration with the Comintern) on military, political, economic and various other matters relative to Japan, and sent it to the Comintern by means of a radio transmitter and in various other ways.

(8) Coded message sent from the Soviet Union to Richard Sorge (25th May, 1940)

Your secondary mission, which is next in importance to your primary mission, is to satisfy the following requirements: We need documents, material, and information concerning the reorganization of the Japanese army. What are the units which make up the new organization? What are the original units which have been inactivated and reorganized? What are the names of the new units ? Who are their commanders ? We are anxious to have detailed information concerning changes in Japanese foreign policy. Reports following events are not enough. We must have advance information.

(9) Operation Barbarossa directive issued by Adolf Hitler on 18th December, 1940.

In the zone of operations, divided by the Pripet marshes into a southern and a northern sector, the main effort will be made north of this area. Two army groups will be provided here.

The more southerly of these two army groups - the Centre one of the front as a whole - will be given the task of annihilating the enemy's forces in White Russia by advancing from the area around and north of Warsaw with specially strong armoured and motorized forces. This will make it possible to switch strong mobile formations northward to co-operate with Army Group North in annihilating the enemy's forces fighting in the Baltic States - Army Group North operating from East Prussia in the general direction of Leningrad. Only after having accomplished this most important task, which must be followed by the occupation of Leningrad and Kronstadt, is there to be a continuation of the offensive operations which aim at the capture of Moscow - as a focal centre of communications and armament industry.

Only a surprisingly quick collapse of Russian resistance could justify aiming at both objectives simultaneously.

The Army Group employed south of the Pripet marshes is to make its main effort from the Lublin area in the general direction of Kiev, in order to penetrate deeply into the flank and rear of the Russian forces and then to roll them up along the Dnieper River.

(10) Richard Sorge, confession in October, 1941.

I myself was surprised that I was able to do secret work in Japan for years without being caught by the authorities. I believe that my group and I escaped because we had legitimate occupations which gave us good social standing and inspired confidence in us. I believe that all members of foreign spy rings should have occupations such as newspaper correspondents, missionaries, business representatives, etc. The police did not pay much attention to us beyond sending plain-clothes men to our houses to question the servants. I was never shadowed. I never feared that our secret work would be exposed by the foreign members in the group, but I worried a good deal over the possibility that we should be discovered through our Japanese agents, and just as I expected this was what happened.

(11) Leopold Trepper, the head of the Red Orchestra, kept Joseph Stalin and the Red Army informed of the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union. He wrote about this in his autobiography, The Great Game (1977)

On December 18, 1940, Hitler signed Directive Number 21, better known as Operation Barbarossa. The first sentence of the plan was explicit: "The German armed forces must be ready before the end of the war against Great Britain to defeat the Soviet Union by means of Blitzkrieg."

Richard Sorge warned the Centre immediately; he forwarded them a copy of the directive. Week after week, the heads of Red Army Intelligence received updates on the Wehrmacht's preparations. At the beginning of 1941, Schulze-Boysen sent the Centre precise information on the operation being planned; massive bombardments of Leningrad, Kiev, and Vyborg; the number of divisions involved.

In February, I sent a detailed dispatch giving the exact number of divisions withdrawn from France and Belgium, and sent to the east. In May, through the Soviet military attaché in Vichy, General Susloparov, I sent the proposed plan of attack, and indicated the original date, May 15, then the revised date, and the final date. On May 12, Sorge warned Moscow that 150 German divisions were massed along the frontier.

The Soviet intelligence services were not the only ones in possession of this information. On March 11, 1941, Roosevelt gave the Russian ambassador the plans gathered by American agents for Operation Barbarossa. On the 10th June the English released similar information. Soviet agents working in the frontier zone in Poland and Rumania gave detailed reports on the concentration of troops.

He who closes his eyes sees nothing, even in the full light of day. This was the case with Stalin and his entourage. The generalissimo preferred to trust his political instinct rather than the secret reports piled up on his desk. Convinced that he had signed an eternal pact of friendship with Germany, he sucked on the pipe of peace. He had buried his tomahawk and he was not ready to dig it up.

(12) German official at the Tokyo Embassy (24th October, 1941)

Richard Sorge belongs to the closest circles of Ambassador Ott's friends. It is well known in leading Japanese circles that Sorge had already formed close connections with the Ambassador when the latter was military attaché. Sorge is regarded as one of the best experts on Japan, though his critical attitude towards his host country has often raised considerable displeasure in official Japanese quarters. As stated in the attached telegram, the arrest could be explained by the influence of anglophile groups who are angered at the fall of the Konoye Cabinet, and attribute it, among other things, to German influence. An approach to Prime Minister Tojo, who as Minister of the Interior controls the police, should clear up the affair as soon as possible.

(13) Branko Vukelic, statement while being interrogated in October 1941.

The general atmosphere surrounding our work is one indication that our organization was essentially Communist in character. We held political meetings in a comradely spirit. These meetings were quite untouched by any suggestion of formal discipline. Sorge made it a rule not to become involved in theoretical controversies on political issues. I assume this was in order to avoid the emergence of Trotskyite heresies. Sorge never gave us orders. He only explained what our urgent duty might be; what each of us must do. He would hint to one or two of us what might be the best means of achieving the tasks before us. Or, sometimes, he would say: 'How about taking such and such a course?' Klausen and I, as a matter of fact, were awkward customers, and we behaved in undisciplined ways. Nevertheless, Sorge through all these nine years, except once or twice when he was offended, never adopted an official manner. And even when he was offended, he only appealed to our political conscience and, above all, to the ties of friendship. He never appealed to other motives. He never threatened us; and he never did anything that might be construed as threatening, or as arising from the requirements of official discipline.

This is the most eloquent proof that our group did not possess a military character. The whole atmosphere much resembled that of the Marxist Club to which I had belonged in Yugoslavia. This was thanks in part, of course, to Sorge's personal character. The atmosphere was comradely, quite devoid of military discipline, and of both the good and the bad sides of a military organization.

(14) Statement issued by the official persecutor of Richard Sorge after the war.

Sorge's special relationship to Ambassador Ott, Ozaki's ties with Prime Minister Konoye and others, the social positions of the defendants, and similar considerations made it reasonable to suspect them of having engaged in political activities; and during the course of our investigation we found ample justification for such a suspicion, both Sorge and Ozaki confessing that following the outbreak of the Russo-German war, when a northward thrust had seemed imminent, they had started a political movement aimed at diverting Japan's energies southward against England and the United States.

(15) General Eugen Ott, telegram to Berlin (15th May, 1942)

The charge against the Communist group, in which the Germans Sorge and Klausen are implicated, will be read the day after tomorrow.... As well as Prince Konoye's intimate associate Ozaki and other Japanese, Saionji the grandson of the last Genro Prince and Inukai, the son of the Minister President murdered in 1932, will also be charged. Indictment charges the accused with having carried on espionage for the Communist International. Saionji and Inukai are charged with passing on state secrets to Ozaki, although not aware of his role.

Charge includes a short personal description of Sorge and his statements about known Communist connections in Europe. Sorge, who came to China in 1930 and afterwards to Japan, is said to be the Comintern's contact man for the Japanese group and to have handed over its instructions.

The chief assistant to the Ministry of Justice had informed Minister Kordt that all mention of Sorge's belonging to the Nazi party would be avoided in the wording of the indictment. Japanese justice regards him purely as an international Communist. The head of the European division of the Foreign Ministry added that announcement had become necessary because the Cabinet was interested in people involved. Further releases not intended. The Press will only carry the Ministry of Justice release. He hopes German government will understand the circumstances of the release. In Japanese view the incident will not disturb German-Japanese relations.

(16) After the war Leopold Trepper met General Tominaga, Chief of Staff of the Japanese Army in Manchuria. During the meeting he asked Tominaga about Richard Sorge.

"Do you know anything about Richard Sorge? I asked him.

"Naturally. When the Sorge affair broke out I was Vice-Minister of Defence."

"In that case, why was Sorge sentenced to death at the end of 1941, and not executed until November 7, 1944? Why didn't you propose that he be exchanged? Japan and the USSR were not at war" (The USSR officially declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945)

He cut me off energetically. "Three times we proposed to the Soviet Embassy in Tokyo that Sorge be exchanged for a Japanese prisoner. Three times we got the same answer: "The man called Richard Sorge is unknown to us."

Unknown, Richard Sorge? Unknown, the man who had warned Russia of the German attack, and who had announced in the middle of the battle of Moscow than Japan would not attack the Soviet Union, thus enabling the Soviet chiefs of staff to bring fresh divisions from Siberia? They preferred to let Richard Sorge be executed rather than have another troublesome witness on their hands after the war.

(17) Viktor Mayevsky, Pravda (4th September, 1964)

Richard Sorge is a man whose name will become the symbol of devotion to the great cause of the fight for peace, the symbol of courage and heroism... The struggle against fascism, against a second world war became the purpose of Sorge's life....

In the spring of 1939 he informed Moscow that the Hitlerites would invade Poland on September 1... In April, 1941, Richard Sorge supplied valuable information about the preparation of a Hitlerite attack on the Soviet Union... He said 150 divisions were being concentrated at the borders of the U.S.S.R., supplied a general scheme of the military operations and in some reports, at first by one day off but later exactly, named the date of the attack, June 22...

Analogous information reached Moscow through other channels. But Stalin disregarded it. How many thousands and millions of lives would have been saved had the information from Richard Sorge and others not been sealed up in a safe! Alas, we paid in full for this mistrust and disregard of people which was an inseparable part of the personality cult.

(18) New York Times (5th September, 1964)

The Soviet Union acknowledged today that Richard Sorge, press officer at the German Embassy in Tokyo during World War II, headed a successful Soviet spy ring.

An article in Pravda, the Communist party newspaper, credited Sorge with having supplied information that enabled the Soviet Army to block the German forces driving on Moscow in the fall of 1941.

Sorge was arrested by the Japanese secret police and executed in 1944 after a trial behind closed doors.

The activities of the Sorge spy ring were first made public in a United States Army report prepared by Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, who was a member of the staff of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur in Japan after the war.

The Pravda article said that “many circumstances” had prevented the Soviet authorities from acknowledging earlier the links between Sorge and the Soviet intelligence system.

"Now the time has come to tell about the man whose name will be for future generations a symbol of devotion to the great cause of the fight for peace, a symbol of courage and heroism," the newspaper said....

Reiterating a charge often made against Stalin, the newspaper said that although this and similar warnings had reached Soviet authorities, they were ignored by the dictator.

According to Pravda, Sorge informed Soviet intelligence two months before the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor that the Japanese were getting ready for a war in the Pacific and would not attack the Soviet Far East, as the Russians feared.

This vital information, Pravda said, enabled the Soviet Army to shift urgently needed reinforcements from the Far East to help stop the Germans' advance at the gates of Moscow.

The account was written by Viktor Mayevsky, Pravda's leading political commentator, who visited Sorge's grave in Tokyo during a recent trip to Japan.

Mr. Mayevsky disclosed that a film about the spy, made by Ives Chiampi, a French director, in cooperation with Italian and Japanese studios would soon be shown in the Soviet Union.

The family moved to Germany when Richard was 3 years old. He became a leftist while serving in the German Army in World War I and joined the German Communist party in 1919.

In the nineteen twenties he emigrated to the Soviet Union, where he joined the intelligence service in 1929. After underground work in Shanghai, he showed up in Tokyo in 1933 as a German newspaper correspondent.

There Sorge won the confidence of the German military attaché, Eugen Ott, who upon assuming the ambassadorship in 1938 made Sorge press attaché and informal adviser. The head of the Gestapo's intelligence network in the Far East also maintained a close relationship with Sorge, who was regarded as a devoted Nazi.