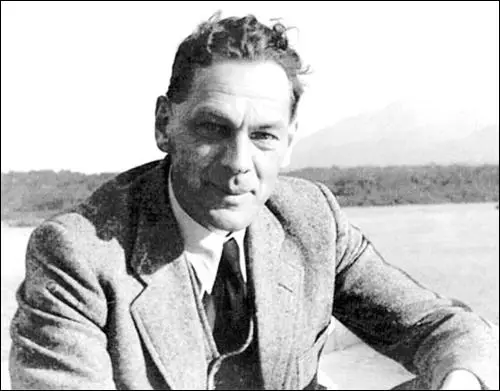

Eugen Ott

Eugen Ott was born on 8th April, 1889. During the First World War he served on the Eastern Front with the 26th (Württemberg) Infantry Division. After the war he became adjutant of General Kurt von Schleicher. Both were members of the Freikorps, who successfully suppressed the German Revolution. (1)

Ott joined the Nazi Party and was lucky to survive when Adolf Hitler became convinced that von Schleicher was involved in a conspiracy to overthrow the Nazi regime and during the Night of the Long Knives, the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) were sent to murder him on 30th June 1934. (2)

In 1934, Ott was sent to Tokyo as military attaché at the German Embassy, where he worked under Herbert von Dirksen. Ott and Dirksen both became close to Richard Sorge, a German journalist, and apparently a passionate supporter of the Nazi Party. In fact, he was a Soviet agent working for the NKVD. His friendship with Dirksen enabled him to find out information about Germany's intentions towards the Soviet Union. Other spies in Sorge's network had access to senior politicians in Japan including prime minister Fumimaro Konoye and they were able to obtain secret details of Japan's foreign policy. (3)

Sorge always maintained that his job as a writer for newspapers and magazines helped him enormously in his quest for intelligence. "A shrewd spy will not spend all his time on the collection of military and political secrets and classified documents. Also, I may add, reliable information cannot be procured by effort alone; espionage work entails the accumulation of information, often fragmentary, covering a broad field, and the drawing of conclusions based thereon. This means that a spy in Japan, for example, must study Japanese history and the racial characteristics of the people and orient himself thoroughly on Japan's politics, society, economics and culture." (4)

Eugen Ott: Ambassador in Tokyo

In 1938 Eugen Ott replaced Herbert von Dirksen as ambassador. Ott, by now aware that Sorge was sleeping with his wife, let his friend Sorge have "free run of the embassy night and day" as one German diplomat later recalled. As the New York Times pointed out: "Sorge won the confidence of the German military attaché, Eugen Ott, who upon assuming the ambassadorship in 1938 made Sorge press attaché and informal adviser. The head of the Gestapo's intelligence network in the Far East also maintained a close relationship with Sorge, who was regarded as a devoted Nazi." (5)

Each morning Sorge would regale Ambassador Ott with gossip and information about Japanese affairs and in return the latter would tell him all manner of things about his own relations with the Japanese. Sorge warned Moscow that Germany was turning from her traditional friendship towards China in favour of an alliance with Japan. This posed a danger to the Soviet Union on two fronts, the east and the west. Sorge warned that Japan would attack wherever the great powers were weakest and the Soviet Union needed to build up her defences in the east. Sorge also forecast that sooner or later Japan would strike a blow against the British Empire. "Singapore," reported Sorge, "is a symbol of British unpreparedness. It is not a citadel, but an open invitation to an adventurous invader and can be taken with comparatively small casualties in less than three days." (6)

In 1939 Leopold Trepper, an agent for the NKVD, established the Red Orchestra network and organised underground operations in several countries. Richard Sorge was one of its key agents. Others in the group included Ursula Beurton, Harro Schulze-Boysen, Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Arvid Harnack, Mildred Harnack, Sandor Rado, Adam Kuckhoff and Greta Kuckhoff. Arvid Harnack, who worked in the Ministry of Economics, had access to information about Hitler's war plans, and became an important spy. Harnack had a close relationship with Donald Heath, the First Secretary at the US Embassy in Berlin. (7) According to Viktor Mayevsky, in the spring of 1939, Sorge told Moscow that Germany would invade Poland on 1st September, 1939. (8)

Operation Barbarossa

On 18th December, 1940, Adolf Hitler signed Directive Number 21, better known as Operation Barbarossa. It included the following: "The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign even before the conclusion of the war against England. For this purpose the Army will have to employ all available units, with the reservation that the occupied territories must be secured against surprises. For the Luftwaffe it will be a matter of releasing such strong forces for the eastern campaign in support of the Army that a quick completion of the ground operations can be counted on and that damage to eastern German territory by enemy air attacks will be as slight as possible. This concentration of the main effort in the East is limited by the requirement that the entire combat and armament area dominated by us must remain adequately protected against enemy air attacks and that the offensive operations against England, particularly against her supply lines, must not be permitted to break down. The main effort of the Navy will remain unequivocally directed against England even during an eastern campaign. I shall order the concentration against Soviet Russia possibly 8 weeks before the intended beginning of operations. Preparations requiring more time to get under way are to be started now - if this has not yet been done - and are to be completed by May 15, 1941." (9)

Within days Richard Sorge had sent a copy of this directive to the NKVD headquarters. Over the next few weeks the NKVD received updates on German preparations. At the beginning of 1941, Harro Schulze-Boysen, sent the NKVD precise information on the operation being planned, including bombing targets and the number of troops involved. In early May, 1941, Leopold Trepper gave the revised date of 21st June for the start of the Operation Barbarossa. On 12th May, Sorge warned Moscow that 150 German divisions were massed along the frontier. Three days later Sorge and Schulze-Boysen confirmed that 21st June would be the date of the invasion of the Soviet Union. (10)

In early June, 1941, Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, the German ambassador, held a meeting in Moscow with Vladimir Dekanozov, the Soviet ambassador in Berlin, and warned him that Hitler was planning to give orders to invade the Soviet Union. Dekanozov, astonished at such a revelation, immediately suspected a trick. When Stalin was told the news he told the Politburo it was all part of a plot by Winston Churchill to start a war between the Soviet Union and Germany: "Disinformation has now reached ambassadorial level!" (11)

On 16th June, 1941, an agent cabled NKVD headquarters that intelligence from the networks indicated that "all of the military training by Germany in preparation for its attack on the Soviet Union is complete, and the strike may be expected at any time.". Later Soviet historians counted over a hundred intelligence warnings of preparations for the German attack forwarded to Stalin between 1st January and 21st June. Many of these were from Sorge but by this time Stalin was convinced that he was a double-agent and working on behalf of Britain. Stalin's response to an NKVD report from Schulze-Boysen was "this is not from a source but a disinformer." (12)

On 21st June, 1941, a German sergeant deserted to the Soviet forces. He informed them that the German Army would attack at dawn the following morning. War Commissar Marshal Semyon Timoshenko and Chief of Staff General Georgy Zhukov, went to see Stalin with the news. Stalin reaction was the alleged German deserter was an attempt to provoke the Soviet Union. Stalin did agree to send out a message to all his military commanders: "There has arisen the possibility of a sudden German attack on June 21-22... The German attack may begin with provocations... It is ordered to occupy secretly the strong points on the frontier... to disperse and camouflage planes at special airfields... to have all units battle ready... No other measures are to be employed without special orders." (13)

Stalin now went to bed. At 3.30 a.m. Timoshenko received reports of heavy shelling along the Soviet-German frontier. Timoshenko told Zhukov to call Stalin by telephone: "Like a schoolboy rejecting proof of simple arithmetic, Stalin disbelieved his ears. Breathing heavily, he grunted to Zhukov that no counter-measures should be taken... Stalin's only concession to Zhukov was to rise from his bed and return to Moscow by limousine. There he met Zhukov and Timoshenko along with Molotov, Beria, Voroshilov and Lev Mekhlis.... Pale and bewildered, he sat with them at the table clutching an empty pipe for comfort. He could not accept he was wrong about Hitler. He muttered that the outbreak of hostilities must have originated in a conspiracy within the Wehrmacht... Hitler surely doesn't know about it. He ordered Molotov to get in touch with Ambassador Schulenburg to clarify the situation." (14)

Joseph Stalin was too shocked and embarrassed to tell the people of the Soviet Union that the country had been invaded by Germany. Vyacheslav Molotov was therefore asked to make the radio broadcast. "Today at four o'clock in the morning, German troops attacked our country without making any claims on the Soviet Union and without any declaration of war... Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. We will be victorious." (15)

Pearl Harbour

In the autumn of 1941, Sorge and his comrades provided Stalin with the information that the Japanese were preparing to make war in the Pacific and were concentrating their main forces in that area in the belief that the Germans would defeat the Red Army. (16) According to Pravda, Sorge informed Soviet intelligence two months before Pearl Harbour "that the Japanese were getting ready for a war in the Pacific and would not attack the Soviet Far East, as the Russians feared." (17)

The Japanese became convinced there was a spy inside the German Embassy. They also discovered that an illegal radio transmitter was being used by the Russians in Tokyo. In October, 1941, the Japanese police arrested Yotoku Miyagi, one of the key figures in Sorge's network. He attempted suicide by leaping head-first from an upper-storey window of the police station, but shrubbery broke his fall. Under torture he confessed, and gave the name of Sorge and his associates. (18)

Sorge was placed under surveillance and it was arranged for him to have an affair with Kiyomi, a spy working for the Japanese secret service. One night they were in a restaurant together she noticed the waiter drop a tiny ball of rice paper on the table they were sharing. Sorge picked it up and learned that he was in danger of being arrested and was urged to escape immediately. When he was in the car, Sorge attempted to set fire to the piece of paper. When the lighter failed him he asked Kiyomi for a light, but she pretended she could not give him one. Exasperated, he threw the rice paper out of the window and drove off. Kiyomi asked Sorge to stop the car so that she could warn her parents that she was staying out for the night. He agreed and she rang up the secret police and told them exactly where the paper had been dropped. It was immediately recovered and Sorge was arrested. (19)

Eugen Ott was outraged when he heard that Sorge had been arrested "on suspicion of espionage" and thought it was a "typical case of Japanese espionage hysteria". He told people around him "Sorge a spy? What twaddle! I would put my hand in the fire for the man." Heinrich Loy, a German working in Tokyo, also found it difficult to believe: "I've known Sorge personally for a long time, but this news surprised me and made me realise he was different from other people. Normally people you've known a long time will make a careless slip on some occasion. Particularly when someone drinks like a fish, as Sorge did, you expect that he will reveal his true self. Considering that he managed to conceal his identity up until now, I have to say he was an exceptional man." (20)

Eugen Ott died on 22nd January 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) General Eugen Ott, telegram to Berlin (15th May, 1942)

The charge against the Communist group, in which the Germans Sorge and Klausen are implicated, will be read the day after tomorrow.... As well as Prince Konoye's intimate associate Ozaki and other Japanese, Saionji the grandson of the last Genro Prince and Inukai, the son of the Minister President murdered in 1932, will also be charged. Indictment charges the accused with having carried on espionage for the Communist International. Saionji and Inukai are charged with passing on state secrets to Ozaki, although not aware of his role.

Charge includes a short personal description of Sorge and his statements about known Communist connections in Europe. Sorge, who came to China in 1930 and afterwards to Japan, is said to be the Comintern's contact man for the Japanese group and to have handed over its instructions.

The chief assistant to the Ministry of Justice had informed Minister Kordt that all mention of Sorge's belonging to the Nazi party would be avoided in the wording of the indictment. Japanese justice regards him purely as an international Communist. The head of the European division of the Foreign Ministry added that announcement had become necessary because the Cabinet was interested in people involved. Further releases not intended. The Press will only carry the Ministry of Justice release. He hopes German government will understand the circumstances of the release. In Japanese view the incident will not disturb German-Japanese relations.