Clemence Housman

Clemence Annie Housman, the third child and first daughter of Edward Housman (1831–1894), a solicitor, and his wife, Sarah Jane Williams (1828–1871), was born on 23rd November 1861 at Bromsgrove. Her eldest brother was the poet Alfred Edward Housman and her younger brother was the writer and artist, Laurence Housman. (1)

Clemence's mother died when she was nine, charging her with special responsibility for Laurence, four years her junior. The children were educated by a governess, Miss Milward. After Edward's second marriage, to his cousin Lucy Housman, the family moved to nearby Fockbury House, Catshill. (2)

Clemence worked for her father as a clerk. According to her brother "she was, for two or three years, the expert who worked out all the Income tax calculations for half the County of Worcestershire." (3)

Assisted by a legacy of £500 each, Laurence and Clemence moved to London in November 1883. They found lodgings at 36 Camberwell New Road. (4) Laurence records in his autobiography, The Unexpected Years (1937), that it was only in order to look after him in London that Clemence was eventually "released from the Victorian bonds of home". (5)

Clemence Housman: Novelist and Artist

Clemence trained as a wood-engraver at the City and Guilds South London Technical Art School at Kennington, and at the Millers' Lane City and Guilds School in South Lambeth. Eventually she gained employment as a wood-engraver, at first providing illustrations for such weekly illustrated papers as The Graphic and the Illustrated London News. However, the introduction of photo-mechanical process engraving displaced the craftsman's skill and she found herself redundant. (6)

Laurence Housman studied art at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A talented illustrator, his work was exhibited at the Baillie Gallery, the Fine Art Society, and the New English Art Club. His best known work includes Goblin Market (1893) and The Sensitive Plant (1898). He also published two volumes of poetry, Green Arras (1896) and Spikenard (1898). In 1900 he created great controversy when he published An Englishwoman's Love Letters. It was very successful and it is claimed he received over £2,000 in royalties. During this period he also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (7)

Clemence Housman, wrote her first novel, The Werewolf (1896), to entertain her fellow students in the engraving class at Kennington, It was illustrated by Laurence Housman and published by the Bodley Head. The illustrations highlight the androgynous figure of White Fell, the work's antagonist and titled female lead, and the feminized build of Christian, the story's Christ-like protagonist. The fact that publishers were hesitant to publicize her scandalous representations of the New Woman suggests Clemence’s radical agenda. As Elizabeth Oakley states, “White Fell seems to embody the neurotic fear of the New Woman and her depraved sexual appetite”. (8) The second, novel, The Unknown Sea, was published by Duckworth in 1898. Her third novel, The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis was published in 1905. (9)

Women's Suffrage

Laurence Housman had been converted to the cause of women's suffrage by hearing a speech given by Emmeline Pankhurst. This resulted in him developing "that most uncomfortable thing a social conscience." He added "I was forced, against my inclination, into a higher standard of moral courage than I had ever practised before" and this began his involvement in the "political problems and controversies of the present day." (10)

In 1907, Laurence Housman joined with several other left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould and Charles Mansell-Moullin to formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." (11)

Clemence Housman joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). On 30th June, 1908, she took part in a meeting when it was announced that they intended to march to 10 Downing Street to meet H. H. Asquith. Housman was on the platform with Emmeline Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jessie Stephen, Mary Phillips, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Maud Joachim and Florence Haig. (12)

Suffrage Atelier

On 8th May 1909, Clemence Housman joined Alfred Pearse and Laurence Housman to form the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage). (13) It claimed: "The object of the society is to encourage Artists to forward the Women's movement, and particularly the Enfranchisement of Women, by means of pictorial publications. Each member of the Society shall undertake to give the Society first refusal of any pictorial work intended for publication, dealing with the women's movement. In return the artist will receive a certain percentage of the profits arising from the sale of her or his work." (14)

As Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) has pointed out that along with the Artists' Suffrage League: "Women were able to organise collectively and contribute their professional skills to the suffrage campaign. They designed, printed and embroidered all manner of political material; they taught each other the requisite skills from hand-painting to needlework; they designed major demonstrations and took part in them in their own contingents; they lent their studios for meetings and contributed to exhibitions, bazaars and fund-raising activities." (15)

On 6th May 1911, Herbert Asquith, the prime minister of the Liberal Party government, announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. (16)

In an attempt to put pressure on the government, the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (17)

Other suffrage organisations including the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Women's Freedom League (WFL), Church League for Suffrage, Actresses' Franchise League, Artists' Suffrage League, Suffrage Atelier, Women's Tax Resistance League, Men's League For Women's Suffrage, Fabian Women's Group, Catholic Women's Suffrage Society and the Church Socialist League agreed to join the march. It was argued that "Everything depends on numbers, and if the deputation is sufficiently large, the authorities will be placed in an insurmountable difficulty." (18)

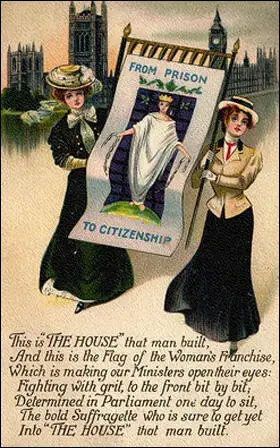

Clemence Housman was heavily involved in the making banners for the Coronation Procession. This included the banner "From Prison to Citizenship" under which "almost 1,000 ex-prisoners marched". The banner was made by Clemence from a design by Laurence. Soon afterwards it was featured on a postcard that was published in a series of twelve entitled, "The House that Man Built." (19)

by Clemence Housman from a design by Laurence Housman (1911)

The Suffrage Atelier was based at 1, Pembroke Cottages, Edwardes Square, the home of Clemence and Laurence Housman. Laurence described his sister as the organistion's "chief worker" and the main "banner-maker" of the women's suffrage campaign. (20) In 1911 she made a new banner for the Actresses' Franchise League. "Stencilled in the AFL colours of pink, white, and green, it shows the twin masks of tragedy and comedy framed with wreaths and ribbons." (21)

Women's Tax Resistance League

In 1906 Dora Montefiore refused to pay her taxes until women were granted the vote. Outside her home she placed a banner that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” As she explained: "I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law."

This resulted in her Hammersmith home being besieged by bailiffs for six weeks. "Towards the end of June, the time was approaching when, according to information brought in from outside the Crown had the power to break open my front door and seize my goods for distraint. I consulted with friends and we agreed that as this was a case of passive resistance, nothing could be done when that crisis came but allow the goods to be distrained without using violence on our part. When, therefore, at the end of those weeks the bailiff carried out his duties, he again moved what he considered sufficient goods to cover the debt and the sale was once again carried out at auction rooms in Hammersmith. A large number of sympathisers were present, but the force of twenty-two police which the Government considered necessary to protect the auctioneer during the proceedings was never required, because again we agreed that it was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of, the authorities." (22)

Montefiore's campaign was supported by Annie Kenney and Teresa Billington-Greig but did not find favour with the leadership of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) and "no effort was ever made to organise the refusal by women to accept laws made for women without their consent. This changed on 22nd October 1909 when the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). (23)

The first member to take part in the campaign was Dr. Octavia Lewin. It was reported in The Daily Chronicle that the "First Passive' Resister", was was to be taken to court. It was announced in the same report that "the Women's Freedom League intends to organise a big passive resistance movement as a weapon in the fight for the franchise." (24)

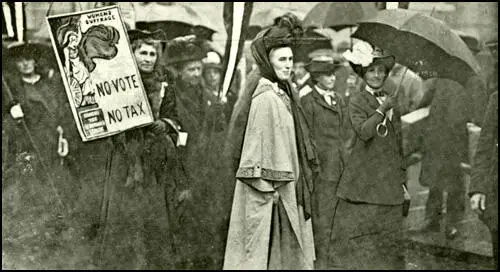

The motto adopted by the Tax Resistance League was "No Vote No Tax". According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000): "When bailiffs seized goods belonging to women in lieu of tax, the TRL made the ensuing sale the occasion for a public or open-air meeting in order to spread the principles of women's suffrage and to rouse public opinion to the injustice of non-representation meted out on tax-paying women." (25)

Clemence Housman was on the committee of the Women's Tax Resistance League. She stated that she refused "to pay her taxes until such time as women are enfranchised". In 1909 Clemence Housman took a house, for which she was taxed inhabited house duty to the amount of 4s. 6d. "This, since she was denied all Parliamentary representation, she refused to pay." It was not until July, 1911, that she received a letter from the Board of Inland Revenue, "stating that legal proceedings had been taken for the recovery of the inhabited house duty, amounted to 4s. 6d. and that unless the tax, plus the costs and out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to £4 18s. 6d., were paid steps would be taken for her arrest and imprisonment." (26)

Clemence refused to pay the fine and on Friday 30th September, she was arrested and conveyed to Holloway Prison. On 7th October a meeting was held to protest about her imprisonment. Christabel Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard and Laurence Housman all made speeches. Pankhurst quoted Clemence as saying. "Holloway is women's polling booth; it is there that I have been able to register my vote against a Government that taxes me without representation." Despard talked about her "courageous act of self-sacrifice, and said that tax resistance was drawing women together in a bond as strong as death." (27)

At the end of the meeting the Women's Tax Resistance League issued a statement. "That this meeting, held at the gates of Holloway Gaol, congratulates Miss Clemence Housman on her refusal to pay Crown taxes without representation, a reassertion of that principle upon which Englishman now enjoy, and also upon the successful outcome of her protest. It condemns the Government's actions in ordering her arrest and imprisonment as a violation of the spirit of the Constitution and of representative government; and it calls upon the Government to give votes to women before again demanding from Miss Housman or any other woman taxpayer the payments of taxes." (28) As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "She (Housman) was released after a week, no reason being given, and did not pay her debt until she received the right to vote." (29)

Later Life

In 1924 Clemence and Laurence Housman moved to Street in Somerset to be with their great friends, Roger and Sarah Bancroft Clark, home of the Clarks' family shoemaking business. Clemence suffered a severe stroke in 1953, and was cared for assiduously by Laurence. She died on 6th December 1955 at Mount Avalon, Glastonbury, having suffered a further stroke, and was buried at Smallcombe cemetery outside Bath. (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Weekly Irish Times (4th July 1908)

The proceeding of the National Women's Social and Political Union excited much interest and gave rise to a good deal of speculation in the Metropolis today. In view of the militant programme of Mrs Pankhurst and her supporters, announcing a deputation to Mr. Asquith, to be followed possibly by a demonstration in Parliament Square, and having in mind also the warning of the police, the question on all lips – "What is likely to happen?" ….

The deputation to Mr. Asquith then left the platform amid cheers. The following are their names: - Mrs. Pankhurst, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence, Miss Clemence Housman, Miss Marie Pethick, Miss Jessie Stephen, Miss Wallace Dunlop, Miss Phillips, Miss Florence Haig, Miss Joachim, Mrs Gibbons, Miss Gibbons, Miss Louvel and Miss Postlethwaite.

(2) Votes for Women (6th October 1911)

Two years ago (1909) Miss Clemence Housman took a house, for which she was taxed inhabited house duty to the amount of 4s. 6d. This, since she was denied all Parliamentary representation, she refused to pay.

In July of this year Miss Housman received a letter from the Board of Inland Revenue, stating that legal proceedings had been taken for the recovery of the inhabited house duty, amounted to 4s. 6d. and that unless the tax, plus the costs and out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to £4 18s. 6d., were paid steps would be taken for her arrest and imprisonment.

Mr. Laurence Housman said that women had awakened to a great sense of political responsibility, and in their fight for enfranchisement they were bound to win. It was impossible to go on denying the vote to the majority of the people of any country when once they possessed that spirit of self-government.

In our last issue we published copies of the correspondence between Miss Clemence Housman and the Inland Revenue Department relating to her refusal to pay her taxes until such time as women are enfranchised, and we stated that her arrest was imminent. On Friday morning (30th September) the blow fell; she was arrested and conveyed to Holloway Prison, where she is still in detention. As a debtor, she is entitled to first-class treatment, including the right to retain her own clothing; on the other hand, the law sets no term to the period of her incarceration.

The principle for which Miss Housman is contending is not now. It is the same old principle for which John Hampden risked his liberty in the seventeenth century, and for which other notable champions of representative government have suffered at different periods of history. But with each new section of the population who was awakened to a sense of their exclusion from citizenship, and who, in consequence, refuse any longer o pay taxes levied without their consent, the problem takes on new forms. The old arguments of opposition are furbished up again: the "divine rights of kings" becomes the "divine rights of men". Damn nature is invoked once more to support the ancient order which is passing away. But all to no purpose. One gentle woman such as is Clemence Housman can dispel by a brave act all their sophistries, and demonstrate over again the truth of the saying that government without the consent of the governed is impossible.

(3) Statement made by the Women's Tax Resistance League (7th October 1911)

That this meeting, held at the gates of Holloway Gaol, congratulates Miss Clemence Housman on her refusal to pay Crown taxes without representation, a reassertion of that principle upon which Englishman now enjoy, and also upon the successful outcome of her protest. It condemns the Government's actions in ordering her arrest and imprisonment as a violation of the spirit of the Constitution and of representative government; and it calls upon the Government to give votes to women before again demanding from Miss Housman or any other woman taxpayer the payments of taxes.

(4) The Vote (14th October 1911)

Miss Christabel Pankhurst was in her place on the cart, surrounded by the speakers. One's eyes were rivetted by the sight of the tall, self-possessed lady, quiet and undemonstrative, who scarcely twenty-four hours before had been inside those prison walls. The singing and the enthusiasm were to reach her in her cell, but the action of the authorities in releasing Miss Housman enabled her to be seen instead of the unseen centre of the demonstration. Her words, too, carried great weight. Humorously she contrasted the treatment of men voters and voteless women: agents to do everything for the men, motors to take them to the polling booth….

Turning to the prison, Miss Housman exclaiming dramatically. "Holloway is women's polling booth; it is there that I have been able to register my vote against a Government that taxes me without representation." Only words of courtesy were heard concerning all the officials with whom Miss Housman had come into contact, and she was cheered to the echo when she declared that, glad as she was to be outside Holloway, she was ready to go back again to win the fight for the recognition of women's citizenship.

"If that great act of justice, the Conciliation Bill, fails to carry next year, there will be not merely one but hundreds of women in prison to make the nation realise that justice is not being done." Thus spoke Mr. Laurence Housman, whose pride in his sister's devotion to the woman's cause was shared by those who listened. Women were only doing what men had gloried in doing in times past, he added, they were struggling for constitutional liberties; women, too, had caught the spirit of democracy. Mrs. Despard, heedless of the drenching rain, made an appeal which touched the hearts of all who heard it; she rejoiced to the victory won by Miss Housman's courageous act of self-sacrifice, and said that tax resistance was drawing women together in a bond as strong as death.