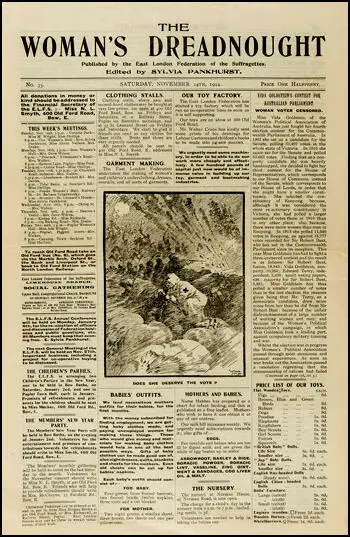

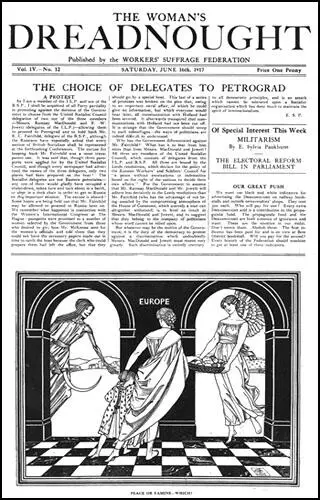

Woman's Dreadnought

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst objected to the formation of the East London Federation of Suffragettes and by the end of 1913 Sylvia was on the verge of being expelled from the WSPU. Christabel, who was living in exile, should meet with her in Paris. "So insistent were the messages… I agreed to go… I was smuggled into a car and driven to Harwich. I insisted that Norah Smyth, who had become financial secretary of the Federation, should go with me to represent our members… Like me, she desired to avoid a breach. Dogged in her fidelities, and by temperament unable to express herself under emotion, she was silent… She (Christabel) urged, a working women's movement was of no value; working women were the weakest portion of the sex: how could it be otherwise? Their lives were too hard, their education too meagre to equip them for the contest." Christabel added: "You have your own ideas. We do not want that; we want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army!". (1)

Christabel also complained about ELF's close links with the Labour Party and the trade union movement. She especially objected to her attending meetings addressed by George Lansbury and James Larkin and her friendship with Keir Hardie and Henry Harben. In view of all this, Christabel concluded, Sylvia's East London suffragettes had to become an entirely separate organization, having proven their inability to operate in compliance with WSPU policy. (2)

In January 1914 Zeli Emerson suggested that the East London Federation of Suffragettes needed its own newspaper. She argued that the Women's Social and Political Union newspaper, The Suffragette, gave little concern to the concerns and cares of working women, and that there was a gap in the market. At a large meeting of ELF members, they chose the name, The Woman's Dreadnought. They agreed that the paper would be sold for a halfpenny for the first four days; any leftover copies would then be distributed for free. (3)

Norah Smyth supplied most of the money for this venture. Zelie Emerson got the project off the ground by consulting printers, producing dummy sheets, deciding the size and format and securing a small amount of advertising. Zelie managed to persuade Lipton's Cocoa and Neave's Food took out three-months trial contracts. Rachel Holmes has argued that "working-class East End suffragettes and socialists were seen as an interesting potential market." (4)

The Woman's Dreadnought first appeared on 8th March 1914. "The name of our paper, The Woman's Dreadnought, is symbolic of the fact that the women who are fighting for freedom must fear nothing... the chief duty of Woman's Dreadnought will be to deal with the franchise question from the working woman's point of view, and to report the activities of the votes for women movement in East London." (5)

Although they printed 20,000 copies of the first edition, by the third issue total sales were only listed as just over 100 copies. During processions and demonstrations, the newspaper was freely distributed as propaganda for the EFF and the wider movement for women's suffrage. (6)

Primary Sources

(1) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931)

I think it was Mary Paterson who suggested the Women's Dreadnought. It would not have been my choice, but the members generally acclaimed it, and I fell in with their view. I wished it had been The Workers' Mate, a name which occurred to me later. "Mate" was a favourite term of address with our people in the East End, and to my mind a most genial and sympathetic one.

It was my earnest desire that it should be a medium through which working women, however unlettered, might express themselves, and find their interests defended. I took infinite plans in correcting and arranging their manuscripts, endeavouring to preserve the spirit and unsophisticated freshness of the original. I wanted the paper to be as far as possible written from life; no dry arguments, but a vivid presentment of things as they are, arguing always from the particular, with all its human features, to the general principle.

(2) In 1920 the American poet, Claude McKay worked for the Workers' Dreadnought.

Sylvia Pankhurst wrote asking me to call at her printing office in Fleet Street. I found a plain little Queen Victoria sized woman with plenty of long unruly bronze-like hair. There was no distinction about her clothes, and on the whole she was very undistinguished. But her eyes were fiery, even a little fanatic, with a glint of shrewdness.

She said she wanted me to do some work for the Workers' Dreadnought. Perhaps I could dig up something along the London docks from the coloured as well as the white seaman and write from a point of view which would be fresh and different. Also I was assigned to read the foreign newspapers from America, India, Australia, and other parts of the British Empire, and mark the items which might interest Dreadnought readers.