John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais, the third of the three surviving children of John William Millais (1800–1870) and his wife, Mary (1789–1864), was born on 8th June 1829 in Portland Street, Southampton. His father did not work and normally described himself as a gentleman.

In 1834 the family moved to St Helier, Jersey. According to his biographer, Malcolm J. Warner: "Millais had already shown remarkable artistic talents and from that year took lessons with a local drawing master named Bessell. He also received guidance from the German artist Edward Henry Wehnert, who lived in St Helier at the time, and encouragement from two prominent men on the island, Sir Hilgrove Turner and Philip Raoul Lemprière, seigneur of Rozel."

Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner took a keen interest in Millais's work and in 1838 advised his parents to move to London so that their gifted son could be trained for a professional career as an artist. The family lived at several different addresses in the area of the British Museum, before taking a lease on 83 Gower Street. Millais attended a school run by the artist, Henry Sass and in 1839–41 he won prizes in the annual drawing competitions for young artists run by the Society of Arts.

On 12th December 1840, aged eleven, Millais became the youngest student ever admitted to the Royal Academy Schools. In 1846 Millais made his début at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition with his painting Pizarro Seizing the Inca of Peru. The following year he won the gold medal for best historical painting. During this period he also produced small genre pictures for art dealer, Ralph Thomas.

Millais became friends with William Holman Hunt, a fellow student at the Royal Academy School. They both rejected the ideas of Joshua Reynolds, who argued in his famous Seven Discourses on Art, that young British artists should follow in the Renaissance tradition, to admire the work of Raphael, and to aspire to the classical ideal "that perfect beauty never found in nature but attainable by the artist through careful selection and improvement". Hunt and Millais reacted against this view and in September 1848 they joined up with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Woolner and James Collinson to establish what became known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Other artists such as Charles Allston Collins and Ford Madox Brown were closely associated with the group but were never official members of the PRB.

The Pre-Raphaelites focused on serious and significant subjects and were best known for painting subjects from modern life and literature often using historical costumes. They painted directly from nature itself, as truthfully as possible and with incredible attention to detail. They were inspired by the advice of John Ruskin, the English critic and author of Modern Painters (1843). He had encouraged artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing."

Millais, who had already developed a reputation as a artist, now tried to put Pre-Raphaelite ideas into practice. His first major painting in the new style was Isabella. According to Malcolm J. Warner: "It shows the use of portraiture as an antidote to idealization, the stiffness of pose intended to recall medieval art, the minute, all-over detail, and the high colour key that characterized early Pre-Raphaelitism."

As Ian Chilvers, the author of Art and Artists (1990) has pointed out: "They (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) chose religious or other morally uplifting themes and had a desire for fidelity to nature that they expressed through detailed observation of flora, etc., and the use of a clear, bright, sharp-focus technique... When their meaning became known in 1850 the group was subjected to violent criticism and abuse."

The most important attack on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood came from Charles Dickens in his journal Household Words on 15th June, 1850: "You will have the goodness to discharge from your minds all Post-Raphael ideas, all religious aspirations, all elevating thoughts, all tender, awful, sorrowful, ennobling, sacred, graceful, or beautiful associations, and to prepare yourselves, as befits such a subject Pre-Raphaelly considered for the lowest depths of what is mean, odious, repulsive, and revolting."

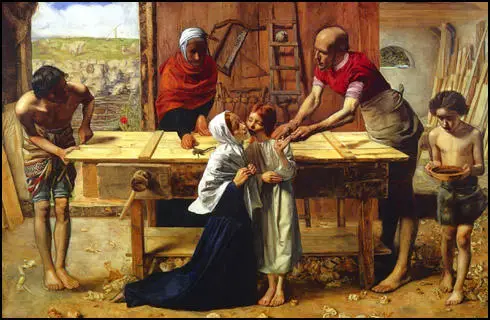

Dickens then went on to criticize Millias's painting, Christ in the House of His Parents, that had appeared for the first time at the 1850 Royal Academy Exhibition: "You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s."

Millais's main patron at the time was James Wyatt, a printseller, and art dealer of Oxford. Wyatt bought his painting Cymon and Iphigenia (1848) and commissioned, Mrs James Wyatt Jr and her Daughter Sarah (1850). Another patron was Thomas Combe, who was printer to Oxford University and the superintendent of the Clarendon Press. Combe purchased Millais's painting, The Return of the Dove to the Ark (1850).

On the 7th May, 1851, The Times accused Millais, William Holman Hunt and Charles Allston Collins of “addicting themselves to a monkish style”, having a “morbid infatuation” and indulging in “monkish follies”. Finally, the works are dismissed as un-English, “with no real claim to figure in any decent collection of English painting.” Six days later John Ruskin had a letter published in the newspaper, where he came to the defence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In another letter published on 30th May, Ruskin claimed that PRB “may, as they gain experience, lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”.

Ruskin now published a pamphlet entitled, Pre-Raphaelitism (1851). He argued hat the advice he had given in the first volume of Modern Painters had “at last been carried out, to the very letter, by a group of young men who... have been assailed with the most scurrilous abuse... from the public press.” Aoife Leahy has argued: "Ruskin’s defences had now taken a new and decidedly evangelical tone. he had formed friendships with the Pre-Raphaelite artists on the basis of his letters to The Times and, just as significantly, he had been personally harassed by members of the public for his views."

However, most art critics agreed with Dickens rather than Ruskin. As Lucinda Hawksley has pointed out: "Millais... was one of seven young artists, all of whom were Royal Academy trained, who formed a group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (known as the PRB). They disagreed with many of the principles of art as defined by the rigid government of the Royal Academy and wanted to paint in the style that had been popular in Italy before the advent of Raphael. When the authorities and the public discovered - by an unfortunate chance - what the letters PRB stood for, they were furious at the group's perceived arrogance and actively turned against them, their followers and anyone who assumed a Pre-Raphaelite style of painting. It was several years before artists who painted in this style were accepted back into mainstream galleries. Millais was one of the fortunate few who was not ruined by the furore, largely because he was kept financially secure by family money."

In the summer 1851 Millais began what is now considered his masterpiece of outdoor Pre-Raphaelite painting, Ophelia (1852). Malcolm J. Warner has pointed out: "He painted the background of painstakingly observed plants and flowers, some chosen for their symbolic significance, from a spot on the Hogsmill River, near Ewell in Surrey.... His background took some four months to complete, and he added the figure of Ophelia in his studio in Gower Street during the following winter. As a model he used Elizabeth Siddall, the favourite model and eventually the wife of D. G. Rossetti. According to the biography of Millais by his son John Guille Millais, Siddall posed in a bath full of water kept warm by lamps underneath. One day the lamps went out and she caught a severe cold, at which her father threatened the artist with legal action until he agreed to pay her doctor's bills."

Millais's next painting, A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew's Day, Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge at the 1852 Royal Academy Exhibition. This painting was extremely popular with the public and on 7th November 1853 he was elected as an associate of the Royal Academy. This was followed by series of historical paintings: The Proscribed Royalist: 1651 (1853), The Order of Release, 1746 (1853) and The Rescue (1854).

Millais went on holiday to Scotland with John Ruskin and his wife, Effie Ruskin. On their return Millais gave Effie drawing lessons. The couple fell in love and began to live together. Effie wrote to her father explaining that her marriage had not been consummated. "He alleged various reasons, hatred to children, religious motives, a desire to preserve my beauty, and, finally this last year he told me his true reason... that he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April." Robert Hewison has argued: "This has been interpreted as meaning that Ruskin was equally innocent, especially in the matter of female pubic hair, but this seems unlikely, as he had seen erotic images belonging to fellow undergraduates at Oxford. There is also speculation that Effie's menstrual cycle interfered with consummation, which is plausible but not provable."

John Ruskin admitted that he loved Effie passionately when he met her for the first time in 1840. After they were married he wistfully told her that "the sight of you, in your girlish beauty, which I might have had." As Suzanne Fagence Cooper, the author of The Passionate Lives of Effie Gray, Ruskin and Millais (2012) has pointed out: "John Ruskin loved young girls, innocents on the verge of womanhood. He became enchanted with twelve-year-old Effie when she visited Herne Hill in the late summer of 1840. The next time he saw her, John Ruskin felt she was 'very graceful but had lost something of her good looks'. After he had won her hand in 1847 and she was still only nineteen... Effie was too old to be truly desirable."

On 15th July 1854 Effie was granted a decree of nullity dissolving the marriage on the grounds of non-consummation. Ruskin wrote a letter to Millais stating that he wanted to remain friends. Millais replied: "I can scarcely see how you conceive it possible that I can desire to continue on terms of intimacy with you". Millais married Effie in 1855 and over the next few years she gave birth to eight children: Everett (1856); George (1857); Effie (1858); Mary (1860); Alice (1862); Geoffroy (1863); John (1865) and Sophie (1868).

As Ian Chilvers has pointed out: "In the 1850s Millais's style changed, as he moved away from the brilliantly coloured, minutely detailed Pre-Raphaelite manner to a broader and more fluent way of painting." Millais defended this change by pointing out that with a family to support he could not afford to spend a whole day working on an area "no larger than a five shilling piece."

Millais's closest male friend at this stage of his life was John Leech, who had become famous for his work on Punch Magazine. Millais met Charles Dickens at the home of his son-in-law, Charles Allston Collins. Despite the attack that Dickens had made on Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents, five years previously, the two men got on well together. The following day Dickens sent Millais a note in which he expressed admiration for his genius. On Dickens suggestion, in 1855 Millais joined the Garrick Club. He was proposed by two of Dickens's friends, William Makepeace Thackeray and Wilkie Collins.

In 1859 Millais began contributing regularly to the magazine Once a Week, and from 1860 he illustrated a series of novels by Anthony Trollope. This included Framley Parsonage (1860), Orley Farm (1861) and The Small House at Allington (1862). Trollope said he was so pleased with the artist's illustrations that it actually helped him develop the characters in sequels. Malcolm J. Warner has pointed out: "His career as an illustrator reached its climax with The Parables of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, which appeared first in Good Words in 1863, then as a separate volume in 1864. He increased his return on many of his more successful illustrations by painting versions in watercolour for sale to dealers and collectors. After the Parables were published his output in illustrations fell off. No doubt he became more conscious of the inferior professional status of this kind of work after his election as a Royal Academician in 1863."

In January, 1866, John Ruskin, aged forty-six, proposed marriage to nineteen year old, Rose La Touche. She did not reject Ruskin but asked him to wait for three years. John La Touche and his wife were opposed to the marriage and Ruskin was only able to communicate with Rosa by using intermediaries, such as George MacDonald, Georgiana Cowper and Joan Agnew. In 1870 Ruskin proposed marriage again. In October, 1870, Marie wrote to Effie Millais seeking evidence of Ruskin's impotence in order to stop the marriage. Effie confirmed this and stated that Ruskin was "utterly incapable of making a woman happy". She added that "he is quite unnatural... and his conduct to me was impure in the highest degree." She ended her letter by saying, "My nervous system was so shaken that I never will recover, but I hope your daughter will be saved."

Millais became concerned about the impact that this correspondence was having on his wife. He wrote to Rose's parents begging them to leave his wife alone. He insisted that "the facts are known to the world, solemnly sworn in God's house" and asked why this "indelicate enquiry necessary". Millais then went on to argue that Ruskin's "conduct was simply infamous, and to this day my wife suffers from the suppressed misery she endured with him." Millais feared that a consummated marriage with Rose would render the previous grounds for annulment void, and would make his marriage to Effie bigamous. Rose La Touche died aged twenty-seven and John Ruskin remained unmarried.

On 20th August, 1869, Charles Dickens wrote to Frederic Chapman inviting him to make a proposal for publishing his new novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. The following month he informed Chapman that he had chosen his son-in-law, Charles Allston Collins, to illustrate the book. Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens (2009), has pointed out: "Dickens... anxious, no doubt, to put his constantly ailing son-in-law in the way of earning some money... but wanted to see what he could do in the way of cover-design before he was formally commissioned."

Collins designed a cover that Dickens was pleased with. However, soon afterwards he wrote to Frederic Chapman: "Charles Collins finds that the sitting down to draw, brings back all the worst symptoms of the old illness that occasioned him to leave his old pursuit of painting; and here we are suddenly without an illustrator! We will use his cover of course, but he gives in altogether as to further subjects."

Charles Dickens asked Millais to find a replacement for Collins. Soon afterwards he saw the drawing Houseless and Hungry in the first issue of The Graphic (4th December 1869). This was the work of the young artist, Luke Fildes. Millais burst into Dickens's room crying "I've got him". Dickens wrote to Fildes: "I see that you are an adept at drawing scamps, send me some specimens of pretty ladies." When he received this pictures he replied: "I can honestly assure you that I entertain the greatest admiration for your remarkable powers." Fildes wrote to his artist friend, Henry Woods: "Congratulate me! I am to do Dickens's story. Just got the letter settling the matter. Going to see Dickens on Saturday... My heart fails me a little for it is the turning point in my career. I shall be judged by this."

Malcolm J. Warner has argued: "In the 1860s Millais developed a painterly technique and a taste for the old masters that ran contrary to the Pre-Raphaelite principles of his youth. His later style pays homage to Velázquez, to Frans Hals, and above all to English portraiture of the previous century. In 1868, with his pendant paintings Stella and Vanessa, he began a line in paintings of attractive young women in eighteenth-century fancy dress, helping to foster an eighteenth-century revival - part of the broader trend in British art known as the aesthetic movement - that affected art, architecture, and fashion alike. His triple portrait Hearts are Trumps is a variation on a theme from Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait The Ladies Waldegrave and Cherry Ripe alludes to the same artist's Penelope Boothby. Reynolds - whom the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had reviled as ‘Sir Sloshua’ - became Millais's artistic touchstone, especially when it came to the depiction of children. Reynolds's own Discourses urged the modern artist to make quotations and borrowings from the art of the past; in painting ‘souvenirs’ of his portraits Millais was following him in both practice and theory." Carlo Pellegini commented on this trend by publishing a caricature of Millais in Vanity Fair with the caption "A converted pre-Raphaelite".

Charles Dickens died on 8th June, 1870. Millais was invited to draw Dickens's dead face. On 16th June, Kate Dickens Collins wrote to Millais: "Charlie - has just brought down your drawing. It is quite impossible to describe the effect it has had upon us. No one but yourself, I think, could have so perfectly understood the beauty and pathos of his dear face as it lay on that little bed in the dining-room, and no one but a man with genius bright as his own could have so reproduced that face as to make us feel now, when we look at it, that he is still with us in the house. Thank you, dear Mr. Millais, for giving it to me. There is nothing in the world I have, or can ever have, that I shall value half as much. I think you know this, although I can find so few words to tell you how grateful I am."

After the death of her husband, Charles Allston Collins, Millais' friend, Kate Dickens secretly married Charles Edward Perugini at a registry office on 11th September 1873. The witnesses, Henry Thomas Mitcham and Ernest Edward Earle, were strangers and friends and family did not attend the service. However, they did not live together after the wedding. It is assumed that the reason for this secret marriage was because Kate thought she was pregnant. The official wedding of Carlo and Kate took place on 4th June 1874 at St. Paul's Church in Wilton Place, Knightsbridge. Millais offered to paint Kate's portrait as a wedding present. However, it took six years to finish.

In 1873 Millais bought a site on Palace Gate in Kensington and engaged the architect Philip Hardwick to build him a new house. The Millais family moved in during the early months of 1877. The impressive house reflected the artist's growing wealth and social standing. It is claimed that during a visit to the house, Thomas Carlyle is said to have remarked: "Millais, did painting do all that? Well, there must be more fools in this world than I had thought!"

Millais now concentrated on painting the portraits of the rich and famous. This included William Ewart Gladstone, Lillie Langtry, Benjamin Disraeli, Alfred Tennyson and Henry Irving. Millais's fee for a commissioned three-quarter length portrait, was normally £1,000. He told one friend: "For the last ten years I should have made £40,000 had I not given myself a holiday of four months in the year: what I did actually make was £30,000, so that I gave an estimate considerably under the fact!"

Ian Chilvers, the author of Art and Artists (1990) has argued: "He became enormously popular... Millais lived in some splendor on his huge income, in 1885 became the first artist to be awarded a baronetcy, and in the year of his death was elected President of the Royal Academy. To some contemporaries it seemed that he wasted his talents pandering to public taste, and many 20th century critics have presented him as a young genius who sacrificed his artistic conscience for money."

In 1893, John Everett Millais, who was a heavy smoker, was diagnosed with cancer of the larynx. On 11th May, 1896, the famous surgeon, Frederick Treves, performed an emergency tracheotomy, to enable him to breathe. Millais died at home on the afternoon of 13th August 1896, aged sixty-seven.

Primary Sources

(1) Lucinda Hawksley , Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter (2006)

Millais first grew to prominence over a scandal - a scandal associated with the artistic movement of which he was a founder member: Pre-Raphaelitism. He was one of seven young artists, all of whom were Royal Academy trained, who formed a group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (known as the PRB). They disagreed with many of the principles of art as defined by the rigid government of the Royal Academy and wanted to paint in the style that had been popular in Italy before the advent of Raphael. When the authorities and the public discovered - by an unfortunate chance - what the letters PRB stood for, they were furious at the group's perceived arrogance and actively turned against them, their followers and anyone who assumed a Pre-Raphaelite style of painting. It was several years before artists who painted in this style were accepted back into mainstream galleries. Millais was one of the fortunate few who was not ruined by the furore, largely because he was kept financially secure by family money.

(2) Charles Dickens, Household Words (15th June, 1850)

This age is so perverse, and is so very short of faith in consequence, as some suppose, of there having been a run on that bank for a few generations that a parallel and beautiful idea, generally known among the ignorant as the Young England hallucination, unhappily expired before it could run alone, to the great grief of a small but a very select circle of mourners. There is something so fascinating, to a mind capable of any serious reflection, in the notion of ignoring all that has been done for the happiness and elevation of mankind during three or four centuries o slow and dearly-bought amelioration, that we have always thought it would tend soundly to the disapprovement of the general public, is any tangible symbol, any outward and visible sign, expressive of that admirable conception could be held up before them. We are happy to have found such a sign at last; and although it would make a very indifferent sign, indeed, in the Licensed Victualling sense of the word, and would probably be rejected with contempt and horror by any Christian publican, it has our warmest philosophical appreciation.

In the fifteenth century, a certain feeble lamp of art arose in the Italian town of Urbino. This poor light, Raphael Sanzio by name, better known to a few miserably mistaken wretches in these later days, as Raphael (another burned at the same time, called Titian), was fed with a preposterous idea of Beauty with a ridiculous power of etherealising, and exalting to the Very Heaven of Heavens, what was most sublime and lovely in the expression of the human face divine on Earth with the truly contemptible conceit of finding in poor humanity the fallen likeness of the angels of GOD, as raising it up again to their pure spiritual condition. This very fantastic whim effected a low revolution in Art, in this wise, that Beauty came to be regarded as one of its indispensable elements. In this very poor delusion, Artists have continued until the present nineteenth century, when it was reserved for some bold aspirants to "put it down."

The Pre-Raphael Brotherhood, Ladies and Gentlemen, is the dread Tribunal which is to set this matter right. Walk up, walk up and here, conspicuous on the wall of the Royal Academy of Art in England, in the eighty-second year of their annual exhibition, you shall see what this new Holy Brotherhood, this terrible Police that is to disperse all Post-Raphael offenders, has "been and done!"

You come in this Royal Academy Exhibition, which is familiar with the works of Wilkie, Collins, Etty, Eastlake, Mulready, Leslie, Maclise, Turner, Stanfield, Landseer, Roberts, Danby, Creswick, Lee, Webster, Herbert, Dyce, Cope, and others who would have been renowned as great masters in any age or country you come, in this place, to the contemplation of a Holy Family. You will have the goodness to discharge from your minds all Post-Raphael ideas, all religious aspirations, all elevating thoughts, all tender, awful, sorrowful, ennobling, sacred, graceful, or beautiful associations, and to prepare yourselves, as befits such a subject Pre-Raphaelly considered for the lowest depths of what is mean, odious, repulsive, and revolting.

You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s.

This, in the nineteenth century, and in the eighty-second year of the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Art, is the Pre-Raphael representation to us, Ladies and Gentlemen, of the most solemn passage which our minds can ever approach. This, in the nineteenth century, and in the eighty-second year of the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Art, is what Pre-Raphael Art can do to render reverence and homage to the faith in which we live and die! Consider this picture well. Consider the pleasure we should have in a similar Pre-Raphael rendering of a favourite horse, or dog, or cat; and, coming fresh from a pretty considerable turmoil about "desecration" in connection with the National Post Office, let us extol this great achievement, and commend the National Academy!

In further considering this symbol of the great retrogressive principle, it is particularly gratifying to observe that such objects as the shavings which are strewn on the carpenter’s floor are admirably painted; and that the Pre-Raphael Brother is indisputably accomplished in the manipulation of his art. It is gratifying to observe this, because the feat involves no low effort at notoriety; everybody knowing that it is by no means easier to call attention to a very indifferent pig with five legs, than to a symmetrical pig with four. Also, because it is good to know that the National Academy thoroughly feels and comprehends the high range and exalted purposes of Art; distinctly perceives that Art includes something more than the faithful portraiture of shavings, or the skilful colouring of drapery imperatively requires, in short, that it shall be informed with mind and sentiment; will on no account reduce it to a narrow question of trade-juggling with a palette, palette-knife, and paint-box. It is likewise pleasing to reflect that the great educational establishment foresees the difficulty into which it would be led, by attaching greater weight to mere handicraft, than to any other consideration even to considerations of common reverence or decency; which absurd principle, in the event of a skilful painter of the figure becoming a very little more perverted in his taste, than certain skilful painters are just now, might place Her Gracious Majesty in a very painful position, one of these fine Private View Days.

Would it were in our power to congratulate our readers on the hopeful prospects of the great retrogressive principle, of which this thoughtful picture is the sign and emblem! Would that we could give our readers encouraging assurance of a healthy demand for Old Lamps in exchange for New ones, and a steady improvement in the Old Lamp Market! The perversity of mankind is such, and the untoward arrangements of Providence are such, that we cannot lay that flattering unction to their souls. We can only report what Brotherhoods, stimulated by this sign, are forming; and what opportunities will be presented to the people, if the people will but accept them.

(3) Lucinda Hawksley , Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter (2006)

By the 1870s Millais had overcome what must have seemed like overwhelming criticism of two of his works, Christ in the Carpenter's Shop (1850) and Sir Isumbras at the Ford (1857); he was now adored by the masses and the establishment and it seemed that nothing he painted could ever disappoint the art collectors. Yet despite his large and steady income, Millais' outgoings were sometimes prohibitive, with an ever-growing family, studio costs and an expensive lifestyle to be supported. Until this time, he had concentrated on crowd-pleasing genre paintings and, during the 1860s in particular, book illustrations, but as the 1870s progressed, Millais decided it was time for a change. Now in his forties, he began a new phase in his career, as a portrait painter - a profession that could prove highly lucrative.

The precocious nine-year-old genius - who had once so maddened his older, fellow Royal Academy pupils that they had dangled him out of a window by his feet until he passed out with fear - and a one-time Pre-Raphaelite rebel was now at the height of his fame. He could choose precisely whom to paint and what price to charge. His portraits, which would later include the society beauty Lily Langtry (1878) and the portrait painter Louise Jopling (1879), excited the rich and famous to clamour for his attention.

(4) Aoife Leahy, Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1850s (1999)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood itself lost its cohesion as a group in 1853 and no longer held meetings after this date. Ruskin, however, continued for some time to write about these same artists and the movement they had inspired in confident tones, with no note of disharmony. Fortunately, he had generally referred to the Pre-Raphaelites as a school and continued to do so in a seamless fashion. Having begun to defend the P.R.B. at a rather late stage, Ruskin seems to over-compensate by making no mention of the group’s break-up in his critical writings. In his published notes on the Royal Academy exhibition of 1856, he pointed out that a significant change had taken place and his tone is almost ecstatic. His narrative seems to peak here, as his imagery is that of a Holy War between Raphael and the Pre-Raphaelites; “the battle is completely and confessedly won” as painters have abandoned Raphael, “struggling forward out of their conventionalism to the pre-Raphaelite standard”. The desired goal has been attained, as the majority of the exhibited works now show a clear Pre-Raphaelite influence and the Grand Style is no longer the accepted norm. The following year’s Academy notes would begin to register some disillusionment, but for now Ruskin was triumphant as the vindicated standard-bearer of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.