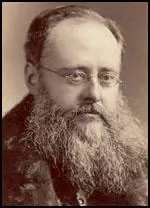

Wilkie Collins

Wilkie Collins, the elder of the two children of the painter William John Thomas Collins (1788–1847), and his wife, Harriet Geddes Collins (1790–1868), was born at 11 New Cavendish Street, St Marylebone, on 8th January 1824. He was named after his godfather, the painter, David Wilkie.

According to his biographer, Catherine Peters: "He was born with a prominent bulge on the right side of his forehead, and his head and shoulders were disproportionately large for his short body and very small hands and feet. He was short-sighted, clumsy, and unathletic, though otherwise healthy as a child, and he later wore glasses."

In 1826 the family moved to Hampstead. His brother, Charles Allston Collins, was born two years later. He was at first educated by his mother, who had worked as a governess before her marriage. In January 1835 he was sent to a day school, the Maida Hill Academy. However, in September 1836, William John Thomas Collins, decided to go on a two year tour of France and Italy. He later recalled that he learned more "among the scenery, the pictures, and the people, than I ever learned at school".

On their return in 1838 the family settled in St John's Wood and Collins attended a boarding-school at 39 Highbury Place, London. Influenced by their father, both boys painted and Wilkie had one of his paintings hung in the Royal Academy summer exhibition of 1849. However, unlike his brother, Charles Allston Collins, he had no interest in working full-time as an artist.

In 1841 Collins found work as a clerk in the Strand offices of a tea merchant, Edward Antrobus. In his spare-time he wrote stories and The Last Stage Coachman appeared in Illuminated Magazine . Collins enrolled as a student of Lincoln's Inn in 1846. He never practised law, but he did obtain a great deal of legal information that he was later to use in his fiction.

William John Thomas Collins died in 1847 leaving his son with enough money to become a full-time writer. His first published book was a biography of his father, Memoirs of the Life of William Collins (1848). This was followed by Antonina (1850), a historical novel set in ancient Rome. Although it received excellent reviews, Collins's next publication was a travel book, Rambles Beyond Railways (1851), based on a journey through Cornwall.

Collins met Charles Dickens in 1851. Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): "Wilkie Collins was... slight, short, bulbous-headed young man (some twelve years younger than Dickens) who was notable for his geniality, his good temper and his cheerfulness... There was a great deal, in other words, to bring them together. Of course there were also many and great contrasts between them, but these personal differences seemed only to endear Collins to Dickens; the younger man was untidy, unpunctual, indolent and alarmingly vague on occasions but for once Dickens did not seem to mind. It is almost as if he saw in Collins some alternative image of himself... The older man had always been too ambitious, too concerned to win money and fame, to allow himself to taste the real pleasures of the young. Was this now something he was trying to recapture in his new friendship? Could he forget himself with Collins; forget his fame, forget his responsibilities, and for a passing time become young again? "

Claire Tomalin , the author of Dickens: A Life (2011), has pointed out: " Wilkie Collins... was a dedicated Bohemian. Dickens saw that he was gifted, a good journalist and a striking storyteller, and found his way of life, easy and unconventional in its dealings with women, interesting. The two men shared a taste for brightly coloured clothes. Collins might appear in a camel-hair suit with broad-striped pink shirt and red tie, and even in sober colours his physical appearance was odd, with his big head and small body, a cast in one eye and a tendency to tics and fidgets.... Wilkie hero-worshipped Dickens, who had risen so high that he did not need to worry any longer about whether lie was a gentleman or not. He became Dickens's chosen companion for many of his escapes and jaunts."

The two men soon became close friends and Collins became a regular contributor to Dickens's periodical Household Words . In 1852 he published Basil (1852), his first novel of contemporary life, which received hostile reviews for its outspoken depiction of sexual obsession. Collins's next novel, Hide and Seek (1854), was dedicated to Dickens was well-liked by the critics. As the author of The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins has pointed out: "The novel has a deaf heroine, the first exploration in his work of the effects of physical handicap on perception and character. This, with the altered states of consciousness caused by mental disturbance, became a lifelong preoccupation, and a feature of his fiction."

In October 1853, Collins joined Augustus Leopold Egg and Dickens on an extensive journey to Switzerland and Italy. Collins's first play, The Lighthouse (1855), was given several performances at Dickens's home, Tavistock House before being professionally produced, with great success, at the Olympic Theatre. Collins's next book, After Dark (1856) was a collection of short stories.

In 1856 Collins spent six weeks in Paris with Dickens. Catherine Peters has argued: "Dickens began to treat Collins less as a disciple and more as a collaborator. Much of their free time was spent together, wandering by night in the less respectable areas of London and Paris, looking for material for their novels and journalism." Kate Dickens later recalled: "I liked him (Wilkie Collins) and my father was very fond of him and enjoyed his company more than that of any other of his friends - Forster was very jealous of their friendship. He had very high spirits and was a splendid companion, but he was as bad as he could be, yet the gentlest and most kind-hearted of men. He took large quantities of opium a day, and consumed sufficient laudanum at night to kill six men."

Collins's health began to deteriorate but he continued to be a productive writer and his novella A Rogue's Life, was serialized in Household Words in 1856. Later that year Dickens managed to persuade Collins to become a member of the regular staff of the journal. In his articles he wrote about the plight of the poor and disadvantaged.

Charles Dickens was unhappily married and he often talked about his domestic problems with his two main friends, Collins and John Forster. In April 1856 Dickens wrote to Foster saying "I find that the skeleton in my domestic closet is becoming a pretty big one." He also said that he feared that "one happiness I have missed in life, and one friend and companion I have never made." Dickens disliked the way his wife had put on weight. He told Collins how he had taken her to his favourite Paris restaurant where she ate so much that she "nearly killed herself".

At this time became sexually involved with Caroline Elizabeth Graves (1829–1895), a young woman with an illegitimate daughter, who ran a shop near his home in Fitzroy Square. The author of The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins (1992) has pointed out: "He suffered from rheumatic disorders and nervous tics that worsened as he aged. He wore clothes that were eccentric in colour and cut. He also, like many ugly men, possessed a charm that made him irresistible to women."

In 1857 Dickens agreed to serialise Collins's Dead Secret in Household Words . Collins was now accepted as one of Britain's leading novelists. The critic, Edmund Yates, argued that Collins's fiction, was exceeded only by that of Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray and Charlotte Brontë.

Collins's ambition to succeed in the theatre was still strong and in 1857 he wrote The Frozen Deep. The inspiration for the play came from the expedition led by Rear-Admiral John Franklin in 1845 to find the North-West Passage. Charles Dickens helped Collins with writing of the play and offered to arrange its first production in his own home, Tavistock House. Dickens also wanted to play the part of the hero, Richard Wardour, who after struggling against jealousy and murderous impulses, sacrifices his life to rescue his rival in love.

Dickens, who grew a beard for the role, also gave parts to three of his children, Charles Culliford Dickens, Kate Dickens, Mamie Dickens and his sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth. Dickens later recalled that taking part in the play was "like writing a book in company... a satisfaction of a most singular kind, which had no exact parallel in my life". Dickens invited the theatre critic from The Times to attend the first production on 6th January, 1857 in the converted schoolroom. He was very impressed and praised Kate for her "fascinating simplicity", Mamie for her "dramatic instinct" and Georgina for her "refined vivacity".

The star of the play was Dickens, who showed he could have had a career as a professional actor. One critic, John Oxenford, said that "his appeal to the imagination of the audience, which conveyed the sense of Wardour's complex and powerful inner life, suggests the support of some strong irrational force". William Makepeace Thackeray , who also saw the production, remarked: "If that man (Dickens) would go upon the stage he would make £20,000 a year."

The temporary theatre held a maximum audience of twenty-five, four performances were given. A private command performance, with the same cast, was also given for Queen Victoria and her family on 4th July and three public benefit performances were given in London in order to raise money for the widow of Dickens's friend, Douglas Jerrold. The play was given three performances in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Dickens, playing the lead, met and fell in love with one of the actresses in the play, the eighteen-year-old Ellen Ternan.

Collins set up house with Caroline Graves at 124 Albany Street. His biographer, Catherine Peters, points out: "He treated her daughter Harriet as an adopted child for whom he took complete responsibility. However, although he made no secret of his domestic arrangements, he was still a man of his time. He never attempted to make Caroline Graves a part of his social life, and although she was introduced to his circle of male friends, she never met their wives or stayed in their houses, where Collins appeared as a bachelor."

In May 1858, Catherine Dickens accidentally received a bracelet meant for Ellen Ternan. Her daughter, Kate Dickens, says her mother was distraught by the incident. Charles Dickens responded by a meeting with his solicitors. By the end of the month he negotiated a settlement where Catherine should have £400 a year and a carriage and the children would live with Dickens. Later, the children insisted they had been forced to live with their father.

Dickens claimed that Catherine's mother and her daughter Helen Hogarth had spread rumours about his relationship with his sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth . Dickens insisted that Mrs Hogarth sign a statement withdrawing her claim that he had been involved in a sexual relationship with Georgina. In return, he would raise Catherine's annual income to £600. On 29th May, 1858, Mrs Hogarth and Helen Hogarth reluctantly put their names to a document which said in part: "Certain statements have been circulated that such differences are occasioned by circumstances deeply affecting the moral character of Mr. Dickens and compromising the reputation and good name of others, we solemnly declare that we now disbelieve such statements." They also promised not to take any legal action against Dickens.

Against the advice of Wilkie Collins and John Forster, in June, 1858, Dickens decided to issue a statement to the press about the rumours involving him and two unnamed women (Nellie Ternan and Georgina Hogarth): "By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth." Dickens also made reference to his problems with Catherine: "Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it."

The statement was published in The Times and Household Words. However, Punch Magazine, edited by his great friend, Mark Lemon, refused, bringing an end to their long friendship. William Makepeace Thackeray also took the side of Catherine and he was also banned from the house. Dickens was so upset that he insisted that his daughters, Mamie Dickens and Kate Dickens, brought an end to their friendship with the children of Lemon and Thackeray. Despite these attempts to cover up his affairs, Dickens was forced to resign from the Garrick Club.

Most of Dickens's friends turned against him over his behaviour towards his wife. Elizabeth Gaskell and William Makepeace Thackeray believed that publicizing his domestic problems was as bad as the separation itself. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was appalled by his behaviour: "What a crime, for a man to use his genius as a cudgel against his near kin, even against the woman he promised to protect tenderly with life and heart - taking advantage of his hold with the public to turn public opinion against her. I call it dreadful." Collins remained friendly with Dickens but it cannot be said that his treatment of his wife did not harm their relationship.

In November 1859, Wilkie Collins agreed for his next novel, The Woman in White to be serialised in All the Year Round . It is considered to be among the first mystery novels and an early example of detective fiction. It was an immediate success and when the novel was published in book form the following year it enabled Collins and Caroline Graves to move to the more expensive Harley Street. Collins was now in a position to employ two servants to help Caroline with the domestic work.

In 1860, Dickens's daughter, Kate Dickens, married Wilkie's brother, Charles Allston Collins. Dickens did not like her new husband and this caused a further rift between the two men. Dickens, who felt he was not free to live with Nellie Ternan , also seemed to disapprove of Collins's open liaison with Caroline Graves.

Wilkie Collins, now financially secure but increasingly unwell, resigned from the staff of All the Year Round to concentrate on writing his novels. Collins followed his success with The Woman in White with three more sensation novels - No Name (1862), Armadale (1866) and The Moonstone (1868). During this period he suffered from "rheumatic gout" and claimed he could not write without taking large doses of laudanum.

Collins also began a sexual relationship with Martha Rudd (1845–1919), a Norfolk shepherd's daughter then working as a servant in the Great Yarmouth area. She was to become the mother of his three children: Marian (4th July 1869), Constance Harriet (14th May 1871) and William Charles Collins (25th December 1874). The author of The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins (1992) has pointed out: " Though more Victorian men than is generally supposed had dual homes and families, Collins avoided marrying either of his two mistresses, Caroline Graves and Martha Rudd. Unwilling to abandon either, he negotiated a compromise where each was aware of the other and eventually accepted the situation."

James T. Fields met him for the first time in November 1873: "Our first visit with Mr. Wilkie Collins - a small man with an odd figure and forehead and shoulders much too large for the rest of him. His talk was rapid and pleasant but not at all inspiring... A man who has been feted and petted in London society, who has overeaten and overdrunk, has been ill, is gouty, and in short is no very wonderful specimen of a human being.

Wilkie Collins died after an attack of bronchitis on 23rd September 1889, at his home in Wimpole Street.

Primary Sources

(1) Claire Tomalin , Dickens: A Life (2011)

A different kind of friend appeared in 1851 in the shape of Wilkie Collins, introduced to him by the artist Augustus Egg. Twelve years younger than Dickens, Collins was the son of a successful artist and just making his way as a writer of fiction. He had read for the Bar, but only at his parents' insistence, and he was a dedicated Bohemian. Dickens saw that he was gifted, a good journalist and a striking storyteller, and found his way of life, easy and unconventional in its dealings with women, interesting. The two men shared a taste for brightly coloured clothes. Collins might appear in a camel-hair suit with broad-striped pink shirt and red tie, and even in sober colours his physical appearance was odd, with his big head and small body, a cast in one eye and a tendency to tics and fidgets.... Wilkie hero-worshipped Dickens, who had risen so high that he did not need to worry any longer about whether lie was a gentleman or not. He became Dickens's chosen companion for many of his escapes and jaunts. In this he replaced Maclise, but he did not replace Forster as the most trusted friend, and Forster continued to receive confidences that were never made to Collins.

(2) Kate Dickens, interviewed in Dickens and Daughter (1939)

I liked him (Wilkie Collins) and my father was very fond of him and enjoyed his company more than that of any other of his friends - Forster was very jealous of their friendship. He had very high spirits and was a splendid companion, but he was as bad as he could be, yet the gentlest and most kind-hearted of men. He took large quantities of opium a day, and consumed sufficient laudanum at night to kill six men.

(3) James T. Fields, diary entry (6th November, 1873)

Our first visit with Mr. Wilkie Collins - a small man with an odd figure and forehead and shoulders much too large for the rest of him. His talk was rapid and pleasant but not at all inspiring... A man who has been feted and petted in London society, who has overeaten and overdrunk, has been ill, is gouty, and in short is no very wonderful specimen of a human being.

(4) Peter Ackroyd , Dickens (1990)

Wilkie Collins was... slight, short, bulbous-headed young man (some twelve years younger than Dickens) who was notable for his geniality, his good temper and his cheerfulness. He already knew such friends of Dickens as the artists Augustus Egg and Daniel Maclise - and this because his father had been a famous painter while his brother, Charles, was already a modestly talented one.

In addition, Collins was a keen admirer of amateur theatricals and had in fact arranged some of his own before joining Dickens's Guild troupe; at the time he met Dickens, he also had plans of becoming a novelist. There was a great deal, in other words, to bring them together. Of course there were also many and great contrasts between them, but these personal differences seemed only to endear Collins to Dickens; the younger man was untidy, unpunctual, indolent and alarmingly vague on occasions but for once Dickens did not seem to mind. It is almost as if he saw in Collins some alternative image of himself. This was what he meant when he described himself as the "Genius of Order" and Collins the "Genius of Disorder". There were also some ways in which Collins was more unconventional than Dickens. He was still a bachelor living with his mother when he first became acquainted with the famous novelist, but within a few years his private life was to take a bizarre turn.

It was not long before Collins was writing for Household Words itself, and eventually he became a member of its small permanent staff. Certainly he began to take his writing seriously after he formed a friendship with Dickens, and there is no doubt that Dickens encouraged and advised the younger man; his first proper novel Basil, was published the year after they met and it seems probable that Collins not only listened to but also took Dickens's advice on the craft of fiction. There were many occasions when they discussed such matters (it also surfaces in their extant correspondence) and as a result Collins came to share the older man's own high claims about the "order" of novelists. He also came to understand the need for care and labour in the preparation of fiction, and it was not long before Dickens was prophesying success for him in the high art which they both espoused. In fact it would not be going too far to say that Wilkie Collins became Dickens's protege and, with the exception of Harrison Ainsworth, it could also fairly be said that he was the only novelist with whom Dickens ever formed a close relationship. Of course their friendship was not founded on literary matters alone - even if Dickens did not subscribe to Collins's "code of morals", as he put it, he realised that he was an easy-going companion with whom he could explore the darker recesses of urban life. In that sense Collins took over the place which Daniel Maclise had once held in his life; as Maclise became more reclusive and wayward, Dickens turned to the young man for companionship in what he would describe as voluptuous or sybaritic jaunts. By which he seems to have meant nothing more than a kind of high-spirited lounging through the more louche areas of London and Paris, as well as visits to the "low" theatres of both capitals. Wilkie Collins was part of a younger generation, in other words, and there is a sense in which he embodied for Dickens all the easy-going and open-hearted bravura of youth which he himself had never experienced. The older man had always been too ambitious, too concerned to win money and fame, to allow himself to taste the real pleasures of the young. Was this now something he was trying to recapture in his new friendship? Could he forget himself with Collins; forget his fame, forget his responsibilities, and for a passing time become young again?