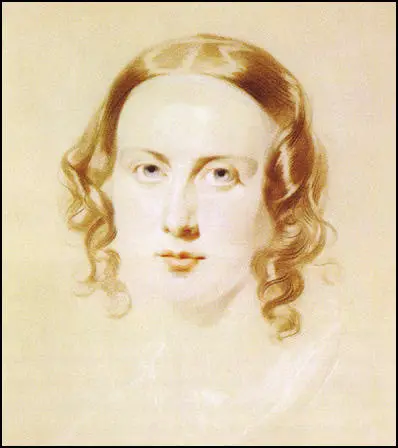

Catherine Hogarth Dickens

Catherine Hogarth was born in Edinburgh on 19th May 1815. Catherine was one of ten children, including Mary Hogarth (1819), Georgina Hogarth (1827) and Helen Hogarth (1833). Her father, George Hogarth, was a talented writer and worked as a journalist for the Edinburgh Courant. In 1817, with Walter Scott and his own brother-in-law James Ballantyne, he bought the Edinburgh Weekly Journal.

In 1830 Hogarth and his family moved to London in order to develop his career as a writer. Claire Tomalin has argued: "He decided to move south, using his knowledge of music and literature to help him find work as a journalist and critic. At first he worked for Harmonicon . In 1831 Hogarth went to Exeter to edit the tory Western Luminary , and in the following year he moved to Halifax as the first editor of the Halifax Guardian. He supplemented his income by doing some teaching in the town.

In 1834 George Hogarth returned to London and was engaged by the The Morning Chronicle as a writer on political and musical subjects. The following year he was appointed as editor of The Evening Chronicle . He became friends with Charles Dickens and commissioned him to write a series of stories under the pseudonym "Boz". Hogarth invited Dickens to visit him at his home in Kensington. The author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "Hogarth... had a large and still growing family, and when he (Dickens) made his first visit to their house on the Fulham Road, surrounded by gardens and orchards, he met their eldest daughter, nineteen-year-old Catherine. Her unaffectedness appealed to him at once, and her being different from the young woman he had known, not only in being Scottish but in coming from an educated family background with literary connections. The Hogarths, like the Beadnells, were a cut above the Dickens family, but they welcomed Dickens warmly as an equal, and George Hogarth's enthusiasm for his work was flattering."

Catherine Hogarth was also impressed by Dickens. In February 1835 she attended a party at Dickens's home. Catherine wrote to her cousin that: "It was in honour of his birthday. It was a batchelors party at his own chambers. His mother and sisters presided. One of them a very pretty girl who sings beautifully. It was a delightful party I enjoyed it very much - Mr Dickens improves very much on acquaintance he is very gentlemanly and pleasant."

One of the daughters, Georgina Hogarth, later recalled that Dickens enjoyed "some delightful musical evenings" where her father performed upon the violoncello. According to Georgina, on one occasion, Dickens "dressed as a sailor jumped in at the window, danced a hornpipe, whistling the tune jumped out again, and a few minutes later Dickens walked gravely in at the door, as if nothing had happened, shook hands all round, and then, at the sight of their puzzled faces, burst into a roar of laughter."

A friend described Catherine as: "A pretty little woman, plump and fresh-colored, with the large, heavy-lidded blue eyes so much admired by men. The nose was slightly retrousse, the forehead good, mouth small, round and red-lipped with a genial smiling expression of countenance, notwithstanding the sleepy look of the slow-moving eyes." Andrew Sanders, the author of Authors in Context: Charles Dickens (2003), has argued: "Dickens's affection for her, and his feeling of real mutual warmth, is evident enough in the letters that survive their courtship but the surviving correspondence suggests little of the adolescent passion that he seems to have felt for Maria Beadnell."

Dickens offer to marry Catherine was immediately accepted. Claire Tomalin has commented: "He (Dickens) saw in her the affection, compliance and physical pleasure, and he believed he was in love with her. That was enough for him to ask her to be his wife.... She was not clever or accomplished like his sister Fanny and could never be his intellectual equal, which may have been part of her charm: foolish little women are more often presented as sexually desirable in his writing than clever, competent ones.... His decision to marry her was quickly made, and he never afterwards gave any account of what had led him to it, perhaps because he came to regard it as the worst mistake in his life."

In the summer of 1835 Charles Dickens took rooms close to the Hogarth house, to be near Catherine. In June he wrote to Catherine urging her to come round and make a late breakfast for him: "It's a childish wish my dear love; but I am anxious to hear and see you the moment I wake - will you indulge me by making breakfast for me... it will be excellent practice for you." On another occasion he wrote that he is "warmly and deeply attached" to her, but he would give her up if she showed him any "coldness".

Charles Dickens married Catherine on 2nd April, 1836, at Lukes Church, Chelsea. After a wedding breakfast at her parents, they went on honeymoon to the village of Chalk, near Gravesend. Dickens wanted to show Catherine the countryside of his childhood. However, he discovered that his wife did not share his passion for long, fast walks. As one biographer put it: "Writing was necessarily his primary occupation, and hers must be to please him as best she could within the limitations of her energy: writing desk and walking boots for him, sofa and domesticity for her."

The couple lived in Furnival's Inn where Dickens had rented three rooms. Mary Hogarth moved in with them when the arrived back after their honeymoon. She stayed for a month but friends said that she always seemed be with Catherine in her new home. Dickens later wrote: "From the day of our marriage, the dear girl had been the grace and life of our home, our constant companion, and the sharer of all our little pleasures."

Mary wrote to her cousin describing Catherine as "a most capital house-keeper... happy as the day is long". She added: "I think they are more devoted than ever since their marriage if that be possible - I am sure you would be delighted with him if you knew him he is such a nice creature and so clever he is courted and made up to by all literary gentlemen, and has more to do in that way than he can well manage."

Catherine Dickens had her first child, Charles Culliford Dickens, on 6th January, 1837. She had difficulty feeding the baby and gave up trying. A wet nurse was found but Mary believed that her sister was suffering from depression: "Every time she (Catherine) sees her baby she has a fit of crying and keeps constantly saying she is sure he (Charles Dickens) will not care for her now she is not able to nurse him."

Dickens now travelled around London with Mary to find a new home. On 18th March he made an offer for 48 Doughty Street. After agreeing to a rent of £80 a year, they moved in two weeks later. Situated in a private road with a gateway and porter at each end. It had twelve rooms on four floors. Mary had one of the bedrooms on the second floor. Dickens employed a cook, a housemaid, a nurse, and later, a manservant.

On 6th May, 1837, Charles, Catherine and Mary Hogarth went to the St James's Theatre to see the play, Is She His Wife ? They went to bed at about one in the morning. Mary went to her room but, before she could undress, gave a cry and collapsed. A doctor was called but was unable to help. Dickens later recalled: "Mary... died in such a calm and gentle sleep, that although I had held her in my arms for some time before, when she was certainly living (for she swallowed a little brandy from my hand) I continued to support her lifeless form, long after her soul had fled to Heaven. This was about three o'clock on the Sunday afternoon." Dickens later recalled: "Thank God she died in my arms and the very last words she whispered were of me." The doctor who treated her believed that she must have had undiagnosed heart problems. Catherine was so shocked by the death of her younger sister that she suffered a miscarriage a few days later.

Peter Ackroyd has argued: "His grief was so intense, in fact, that it represented the most powerful sense of loss and pain he was ever to experience. The deaths of his own parents and children were not to affect him half so much and in his mood of obsessive pain, amounting almost to hysteria, one senses the essential strangeness of the man... It has been surmised that all along Dickens had felt a passionate attachment for her and that her death seemed to him some form of retribution for his unannounced sexual desire - that he had, in a sense, killed her."

Charles Dickens cut off a lock of Mary's hair and kept it in a special case. He also took a ring off her finger and put it on his own, and there it stayed for the rest of his life. Dickens also expressed a wish to be buried with her in the same grave. He also kept all of Mary's clothes and said a couple of years later that "they will moulder away in their secret places". Dickens wrote that he consoled himself "above all... by the thought of one day joining her again where sorrow and separation are unknown". He was so upset by Mary's death that for the first and last time in his life he missed his deadlines and the episodes of The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist which were supposed to be written during that month were postponed.

Dickens told his friend, Thomas Beard: "So perfect a creature never breathed. I knew her inmost heart, and her real worth and values. She had not a fault." He told other friend that "every night she appeared in his dreams". Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens: A life Defined by Writing (2011) has argued: "It was the third great emotional crisis of his life, following the blacking factory experience and the Beadnell affair, and one that profoundly influenced him as an artist as well as a man."

Catherine gave birth to Mary, known as Mamie, on 6th March, 1838. She had been named after her dead aunt, Mary Hogarth. Catherine was unable to breast-feed her daughter and had to employ a wet-nurse. Dickens's best friend, John Forster, became her godfather. Soon afterwards he told Forster that he was falling out of love with Catherine and that the couple were incompatible. Despite this comment he wrote to Catherine on 5th March, 1839, while on holiday in Devon: "To say how much I miss you, would be ridiculous. I miss the children in the morning too and their dear little voices which I have sounds for you and me that we shall never forget."

Catherine's second daughter, Kate Macready, was born on 29th October, 1839. She had been in labour for twelve hours. Dickens' named her after his friend, the actor, William Macready . He gave a great celebration for her christening in August. "Rather a noisy and uproarious day." Dickens got drunk and ended up having an argument with Forster. Catherine was so upset by the dispute that she burst into tears and ran from the room."

In December, 1839, the Dickens family moved from 48 Doughty Street to 1 Devonshire Terrace, York Gate, close Regent's Park. Dickens paid £800 for the eleven-year lease in addition to an annual rent of £160. The house had more than a dozen rooms that included a library, dinning and drawing rooms, several bedrooms and two nurseries for Mamie and Kate. A fourth child, Walter Landor, was born on 8th February, 1841.

Charles Dickens was extremely popular in America. The New York Herald Tribune explained why he was liked: "His mind is American - his soul is republican - his heart is democratic." Despite the high sales of his novels, Dickens did not receive any payment for his work as the country did not abide by international copyright rules. He decided to travel to America in order to put his case for copyright reform.

His publishers, Chapman and Hall , offered to help fund the trip. It was agreed they would pay him £150 a month and that when he returned they would publish the book on the visit, American Notes. Dickens would then receive £200 for each monthly installment. At first, Catherine refused to go to America with her husband. Dickens told his publisher, William Hall: "I can't persuade Mrs. Dickens to go, and leave the children at home; or let me go alone." According to Lillian Nayder, the author of The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth (2011), their friend, the actor, William Macready , persuaded her "that she owed her first duty to her husband and that she could and must leave the children behind."

Dickens and Catherine left on The Britannia from Liverpool on 4th January, 1842. Their ship was a wooden paddle steamer designed for 115 passengers. The Atlantic crossing turned out to be one of the worst the ship's officers had ever known. During one storm the smokestack had to be lashed with chains to stop it being blown over and setting fire to the desks. When they approached Halifax in Nova Scotia, the ship ran aground and they had for the rising tide to release them from the rocks. Catherine wrote to her sister-in-law: "I was nearly distracted with terror and don't know what I should have done had it not been for the great kindness and composure of my dear Charles."

The ship arrived in Boston on 22nd January. While in America the couple visited Worcester, Springfield, Hartford, Philadelphia, New York City and Washington, where they met President John Tyler. At the end of March they visited Niagara Falls. Charles commented: "It would be hard for a man to stand nearer to God than he does there." He was less impressed with Toronto where he disapproved of "its wild and rabid Toryism".

Dickens wrote to John Forster in April: "Catherine really has made a most admirable traveller in every respect. She has never screamed or expressed alarm under circumstances that would have fully justified her in doing so, even in my eyes; has never given way to despondency or fatigue, though we have now been travelling incessantly, through a very rough country... and have been at times... most thoroughly tired; has always accommodated herself, well and cheerfully, to everything; and has pleased me very much." They also spent time in Montreal and Quebec before travelling back to New York City where they got to the boat to Liverpool.

They arrived back in London on 29th June, 1842. Soon afterwards Catherine's fifteen-year-old, sister, Georgina Hogarth, joined them at 1 Devonshire Terrace. As Michael Slater has pointed out: "Georgina went to live with them and began making herself useful to her sister in running the household and coping with the busy social life that centred on Catherine's celebrated husband. She helped especially with the ever increasing number of children, and taught the younger boys to read before they went to school. She deputized for her sister on social occasions when Catherine was unwell and looked after the family during Catherine's pregnancies. Dickens came increasingly to value Georgina's companionship (she was one of the few people who could keep pace with him on his long daily walks). He admired her intelligence and enjoyed her gift for mimicry." Charles also recorded that he thought Georgina was "one of the most amiable and affectionate of girls."

Lucinda Hawksley has argued: "Georgina was to figure very largely in the Dickens children's lives. She assisted with their schooling, cared for them when their parents were absent and became their confidante. Her facial similarity to her dead sister was often remarked upon and, when she arrived to live in Devonshire Terrace, she was almost the same age Mary had been when she had stayed with Catherine and Charles... It is unknown how long Georgina's stay was originally intended to be, but before long she had become accepted as a permanent fixture."

Catherine also had several miscarriages before Francis Jeffrey, was born on 15th January, 1844. He was followed by Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson (28th October, 1845), named after the poet, Alfred Tennyson, and Sydney Smith Haldimand (18th April, 1847). Mamie Dickens later recalled that Dickens inspected every room in the house every morning, checking for tidiness and cleanliness.

Henry Morley met Catherine in the late 1840s: "Dickens has evidently made a comfortable choice. Mrs Dickens is stout, with a round, very round, rather pretty, very pleasant face, and ringlets on each side of it. One sees in five minutes that she loves her husband and her children, and has a warm heart for anybody who won't be satirical, but meet her on her own good natured footing. We were capital friends at once, and had abundant talk together."

Dickens was writing David Copperfield when his eighth child was born on 16th January, 1849. He named him Henry Fielding Dickens after the novelist, Henry Fielding. He told John Forster that this was in "a kind of homage to the style of the novel he was about to write." Henry was the brightest of all the children and later became a successful lawyer.

Richard Henry Dana described Catherine during this period as "natural in her manners and seems not at all elated by her new position". Henry Wadsworth Longfellow added that she was "good-natured... not beautiful but amiable". Another visitor to the house remarked that Catherine was "plain and courteous in her manner, but rather taciturn, leaving the burden of conversation to fall upon her gifted husband... her position as the lion's mate seemed embarrassing to her... amiable and sensible... modest and diffident... kind and patient".

Catherine's next child, Dora Annie Dickens, was named after Dora Spenlow, the dead heroine in the book David Copperfield. She was born on 16th August, 1850. Claire Tomalin has pointed out that Charles Dickens arrived home on 14th April, 1851: "He was in London to preside at the dinner of the General Theatrical Fund, calling at Devonshire Terrace first to see the children in the care of their nurses, and playing with Dora, now nine months old. She seemed perfectly well when he left her for the dinner, but even as he was making his speech she suffered a convulsion and died quite suddenly."

In 1851 Catherine Dickens wrote and published a cookery book, What Shall We Have for Dinner?. Margaret Lane cruelly argued in Purely for Pleasure (1967): "The emphasis on rich and starchy dishes... makes one wonder whether Dickens's growing distaste for his marriage... may not have been - at least partly - due to the fact that while still young she became mountainously fat."

Catherine's last child, Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, was born on 13th March 1852. He was named after the novelist, Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Dickens told Angela Burdett-Coutts that "on the whole I could have dispensed with him". However, "Plorn" as he was called became the spoilt child of the family. He wrote to a friend that "I begin to count the children incorrectly, they are so many; and to find fresh ones coming down to dinner in a perfect procession and I thought there were no more."

Catherine became aware that Dickens was visiting prostitutes. He confessed to Wilkie Collins that he had encountered a prostitute in Paris who he intended to go out looking for the following night. He also told Collins of another prostitute he had befriended. He described Caroline Maynard as "rather small, and young-looking; but pretty and gentle, and had a very good head... There can never have been much evil in her, apart from the early circumstances that directed her steps the wrong way."

After one trip to Italy he wrote to his friend, Emile De La Rue, about Catherine's concerns and jokingly said she had "obtained positive proofs" of Dickens "being on the most confidential terms with at least 15,000 women... since we left Genoa". He told Catherine: "Whatever made you unhappy in the Genoa time had no other root, beginning, middle or end, than whatever has made you proud and honoured in your married life, and given you station better than rank, and surrounded you with many enviable things."

In 1855 Charles Dickens was contacted by his first girlfriend, Maria Beadnell. The letter was later destroyed but Dickens's letters in reply have survived. In his first letter to Maria he wrote: "Your letter is more touching to me from its good and gentle association with the state of Spring in which I was either much more wise or much more foolish than I am now".

In his second letter he told her that he had "got the heartache again" from seeing her handwriting. "Whatever of fancy, romance, energy, passion, aspiration and determination belong to me, I never have separated and never shall separate from the hard hearted little woman - you - whom it is nothing to say I would have died for.... that I began to fight my way out of poverty and obscurity, with one perpetual idea of you... I have never been so good a man since, as I was when you made me wretchedly happy."

Dickens wrote another letter to her claiming their failed relationship changed his personality. The "wasted tenderness of those hard years" made him suppress emotion, "which I know is no part of my original nature, but which makes me chary of showing my affections, even to my children, except when they are very young."

Dickens suggested they met in secret. Maria Beadnell agreed but warned him she was "toothless, fat, old, and ugly", to which he replied, "You are always the same in my remembrance". As Claire Tomalin , the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "The meeting took place. He saw an overweight woman, no longer pretty, who talked foolishly and too much. The edifice he had built up in his mind tumbled, and he beat an immediate retreat. There was, however, a dinner with their two spouses, which allowed him perhaps to compare the appetites and girths of Maria and Catherine and brood on their resemblances."

In April 1856 Dickens wrote to John Forster in reference to his wife: "I find that the skeleton in my domestic closet is becoming a pretty big one." He also said that he feared that "one happiness I have missed in life, and one friend and companion I have never made." Dickens began to question Catherine's intelligence in front of friends. He wrote to a female acquaintance: "It is more clear to me than ever that Kate is as near being a Donkey, as one of that sex... can be." Dickens also disliked the way his wife had put on weight. He told Wilkie Collins how he had taken her to his favourite Paris restaurant where she ate so much that she "nearly killed herself".

In August 1857 Dickens met Ellen Ternan. Two months later he moved out of the master bedroom and now slept alone in a single bed. At the same time he wrote to Emile De La Rue in Genoa, saying that Catherine was insanely jealous of his friendships and that she was unable to get on with her children. He wrote to other friends complaining of Catherine's "weaknesses and jealousies" and that she was suffering from a "confused mind".

Dickens wrote to John Forster to explain his feelings towards Catherine: "Poor Catherine and I are not made for each other, and there is no help for it. It is not only that she makes me uneasy and unhappy, but that I make her so too - and much more so. She is exactly what you know in the way of being amiable and complying, but we are strangely ill-assorted for the bond there is between us. God knows she would have been a thousand times happier if she had married another kind of man, and that her avoidance of this destiny would have been at least equally good for us both. I am often cut to the heart by thinking what a pity it is, for her own sake, that I ever fell in her way; and if I were sick or disabled to-morrow, I know how sorry she would be, and how deeply grieved myself, to think how we had lost each other. But exactly the same incompatibility would arise, the moment I was well again; and nothing on earth could make her understand me, or suit us to each other. Her temperament will not go with mine. It mattered not so much when we had only ourselves to consider, but reasons have been growing since which make it all but hopeless that we should even try to struggle on. What is now befalling me I have seen steadily coming, ever since the days you remember when Mary was born; and I know too well that you cannot, and no one can, help me."

Rumours began to circulate at the Garrick Club that Dickens was having an affair with Georgina Hogarth. As Dickens, biographer, Peter Ackroyd, points out: "There were rumours... that he was having an affair with his own sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth. That she had given birth to his children. More astonishing still, it seems likely that these rumours about Georgina were in fact started or at least not repudiated by the Hogarths themselves." George Hogarth wrote a letter to his solicitor in which he assured him: "The report that I or my wife or daughter have at any time stated or insinuated that any impropriety of conduct had taken place between my daughter Georgina and her brother-in-law Charles Dickens is totally and entirely unfounded."

The author of The Invisible Woman (1990) argues: "The idea of a member of the Garrick Club so distinguished for his celebration of the domestic virtues being caught out in a love affair with a young sister-in-law was certainly scandalous enough to cause a stir of excitement." William Makepeace Thackeray , who was a close friend of Dickens, claimed that he was not having an affair with Georgina but "with an actress".

George Reynolds refered to both Georgina Hogarth and Ellen Ternan in an article published in The Reynold's Weekly newspaper on 13th June 1858: "The names of a female relative and of a professional young lady, have both been, of late, so intimately associated with that of Mr. Dickens, as to excite suspicion and surprise in the minds of those who had hitherto looked upon the popular novelist as a very Joseph in all that regards morality, chastity, and decorum."

Helen Hogarth became convinced that Dickens was having a sexual relationship with Georgina and that this created a terrible rift in the family. Georgina's aunt, Helen Thomson, commented: "Georgina is an enthusiast, and worships Dickens as a man of genius, and has quarrelled with all her relatives because they dared to find fault with him, saying, 'a man of genius ought not to be judged with the common herd of men'. She must bitterly repent, when she recovers from her delusion, her folly; her vanity is no doubt flattered by his praise, but she has disappointed us all."

Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): "Events were now slipping even further out of Dickens's control, and it was at some point in these crucial days that Mrs Hogarth seems to have threatened Dickens with action in the Divorce Court - a very serious step indeed since the Divorce Act of the previous year had decreed that wives could divorce their husbands only on the grounds of incest, bigamy or cruelty. The clear implication here was that Dickens had committed incest with Georgina, which was the legal term for sexual relations with a sister-in-law.... At this point, it seems, the Hogarths implicitly dropped the threat of court action. Yet the bare facts of the matter can hardly suggest the maelstrom of fury and bitterness into which the family, now divided against itself, had descended."

In May 1858, Catherine Dickens accidentally received a bracelet meant for Ellen Ternan. Her daughter, Kate Dickens, says her mother was distraught by the incident. Charles Dickens responded by a meeting with his solicitors. By the end of the month he negotiated a settlement where Catherine should have £400 a year and a carriage and the children would live with Dickens. Later, the children insisted they had been forced to live with their father.

Charles Culliford Dickens refused and decided that he would live with his mother. He told his father in a letter: "Don't suppose that in making my choice, I was actuated by any feeling of preference for my mother to you. God knows I love you dearly, and it will be a hard day for me when I have to part from you and the girls. But in doing as I have done, I hope I am doing my duty, and that you will understand it so."

Dickens wrote to Angela Burdett-Coutts about his marriage to Catherine: "We have been virtually separated for a long time. We must put a wider space between us now, than can be found in one house... If the children loved her, or ever had loved her, this severance would have been a far easier thing than it is. But she has never attached one of them to herself, never played with them in their infancy, never attracted their confidence as they have grown older, never presented herself before them in the aspect of a mother."

Dickens claimed that Catherine's mother and her daughter Helen Hogarth had spread rumours about his relationship with Georgina Hogarth . Dickens insisted that Mrs Hogarth sign a statement withdrawing her claim that he had been involved in a sexual relationship with Georgina. In return, he would raise Catherine's annual income to £600. On 29th May, 1858, Mrs Hogarth and Helen Hogarth reluctantly put their names to a document which said in part: "Certain statements have been circulated that such differences are occasioned by circumstances deeply affecting the moral character of Mr. Dickens and compromising the reputation and good name of others, we solemnly declare that we now disbelieve such statements." They also promised not to take any legal action against Dickens.

Lucinda Hawksley has asked some important questions about Georgina's behaviour during this period: "Georgina Hogarth's role during this tumultuous time will for ever remain a conundrum. When Charles decided to separate from Catherine, the wronged wife's family rallied round her, as could be expected - all of the Hogarths, that is, except for Georgina. It appears that from the start Catherine's closest sister (since Mary's death), who had shared her home and her life for so many years, did not take Catherine's side, nor offer her any form of support. Instead, she elected to stay living with her brother-in-law, as his housekeeper, after he had rejected and humiliated her sister. Why she chose to be shunned by her parents, grandparents and siblings in order to stay with her sister's husband has never been satisfactorily explained; nor how she could be so deliberately cruel to Catherine."

On the signing of the settlement, Catherine found temporary accommodation in Brighton, with her son Charles Culliford Dickens. Later that year she moved to a house in Gloucester Crescent near Regent's Park. Dickens automatically got the right to take away 8 out of the 9 children from his wife (the eldest son who was over 21 was free to stay with his mother). Under the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act, Catherine Dickens could only keep the children she had to charge him with adultery as well as bigamy, incest, sodomy or cruelty.

Charles Dickens now moved back to Tavistock House with Mamie Dickens, Georgina Hogarth, Kate Dickens, Walter Landor Dickens, Henry Fielding Dickens, Francis Jeffrey Dickens, Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson, Sydney Smith Haldimand and Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens. Mamie and Georgina were put in command of the servants and household management.

In June, 1858, Dickens decided to issue a statement to the press about the rumours involving him and two unnamed women (Ellen Ternan and Georgina Hogarth): "By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth."

Dickens also made reference to his problems with Catherine: " Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it."

The statement was published in The Times and Household Words. However, Punch Magazine, edited by his great friend, Mark Lemon, refused, bringing an end to their long friendship. William Makepeace Thackeray also took the side of Catherine and he was also banned from the house. Dickens was so upset that he insisted that his daughters, Mamie Dickens and Kate Dickens, brought an end to their friendship with the children of Lemon and Thackeray.

Dickens also wrote to Charles Culliford Dickens insisting that none of the children should "utter one word to their grandmother" or to Catherine's sister, Helen Hogarth, who had also been accused of talking falsely about his relationship with Ternan: "If they are ever brought into the presence of either of these two, I charge them immediately to leave their mother's house and come back to me." Kate Dickens later recalled: "My father was like a madman... This affair brought out all that was worst - all that was weakest in him. He did not care a damn what happened to any of us. Nothing could surpass the misery and unhappiness of our home."

On 16th August, The New York Tribune, published a letter from Dickens that stated that the marriage had been unhappy for many years and that Georgina Hogarth was responsible for long preventing a separation by her care for the children: "She has remonstrated, reasoned, suffered and toiled, again and again to prevent a separation between Mrs Dickens and me."

In the letter Dickens suggested that Catherine had suggested the separation: "Her always increasing estrangement made a mental disorder under which she sometimes labours - more, that she felt herself unfit for the life she had to lead as my wife and that she would be better far away." The letter goes on to boast of his financial generosity to his wife. He then went onto praise Georgina as having a higher claim on his affection, respect and gratitude than anybody in the world."

Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): " Yet the bare facts of the matter can hardly suggest the maelstrom of fury and bitterness into which the family, now divided against itself, had descended. And what of Dickens himself? From the beginning he had tried to keep everything as neat and as ordered as everything else in his life, but it had spiralled out of control. The case for an informal separation had degenerated into a series of formal negotiations which in turn threatened to lead to public exposure of his domestic life; he, the apostle of family harmony, had even been accused of incest with his own wife's sister. He reacted badly to stress and now, during the most anxious days of his life, he ceased to behave in a wholly rational manner."

Dickens raised the issue of Mrs Hogarth and her daughter Helen Hogarth and the comments they had supposed to have made about Ellen Ternan : "Two wicked persons who should have spoken very differently of me... have... coupled with this separation the name of a young lady for whom I have a great attachment and regard. I will not repeat her name - I honour it too much. Upon my soul and honour, there is not on this earth a more virtuous and spotless creature than this young lady. I know her to be as innocent and pure, and as good as my own dear daughters."

Elizabeth Gaskell and William Makepeace Thackeray believed that publicizing his domestic problems was as bad as the separation itself. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was appalled by his behaviour: "What a crime, for a man to use his genius as a cudgel against his near kin, even against the woman he promised to protect tenderly with life and heart - taking advantage of his hold with the public to turn public opinion against her. I call it dreadful." Kate Dickens later recalled that her father stopped speaking to her for two years when he discovered she had visited her mother. Catherine wrote to Angela Burdett-Coutts: "I have now - God help me - only one course to pursue. One day though not now I may be able to tell you how hardly I have been used."

Georgina Hogarth backed up Dickens's story. In a letter to Maria Winter, Georgina argued: "By some constitutional misfortune and incapacity, my sister always from their infancy, threw her children upon other people, consequently as they grew up, there was not the usual strong tie between them and her - in short, for many years, although we have put a good face upon it, we have been very miserable at home." Hans Christian Anderson, who met Georgina when he stayed in the Dickens household, described her as "piquante, lively and gifted, but not kind" who often made Catherine cry.

Angela Burdett-Coutts remarked: "I knew Charles Dickens well, until after his separation from his wife - she I knew after that breach." Harriet Martineau commented that "old friends, who have been intimate in the family during her whole married life, feel towards her an unaltered respect and regard." Catherine received considerable support from several of Dickens's old friends including, Frederick Evans, Mark Lemon, John Leech and Shirley Brooks.

On 17th July 1860 Kate Dickens married the artist, Charles Collins, at St. Mary's Church in Higham. This was followed by a lavish wedding breakfast at Gad's Hill Place. In the afternoon the guests visited Rochester Castle and in the evening they were entertained by a military band in Chatham. Charles Dickens insisted that Catherine was not invited to the wedding.

Catherine maintained her friendships from the early period of her marriage. This included Mark Lemon , William Makepeace Thackeray , Angela Burdett-Coutts and George Cruikshank. Her daughter, Kate Dickens , was a regular visitor. Catherine and Kate agreed never to talk about Dickens, since it caused only pain to both of them. However, on one occasion, while looking at a photograph of her husband, she asked Kate: "Do you think he is sorry for me?"

Charles Dickens died on 8th June, 1870. The traditional version of his death was given by his official biographer, John Forster. He claimed that Dickens was having dinner with Georgina Hogarth at Gad's Hill Place when he fell to the floor: "Her effort then was to get him on the sofa, but after a slight struggle he sank heavily on his left side... It was now a little over ten minutes past six o'clock. His two daughters came that night with Mr. Frank Beard, who had also been telegraphed for, and whom they met at the station. His eldest son arrived early next morning, and was joined in the evening (too late) by his youngest son from Cambridge. All possible medical aid had been summoned. The surgeon of the neighbourhood (Stephen Steele) was there from the first, and a physician from London (Russell Reynolds) was in attendance as well as Mr. Beard. But human help was unavailing. There was effusion on the brain." Shirley Brooks noted in his diary on 11th July 1870, that Catherine Dickens was "resolved not to allow Forster, or any other biographer, to allerge that she did not make Dickens a happy husband, having letters after the birth of her ninth child, in which Dickens writes like a lover."

After his death of Charles Dickens, her sister Georgina Hogarth, set up house with Mamie Dickens. Georginia told her friend, Annie Fields, "nothing will ever fill up that empty place, nor will life ever again have any real interest for me." On the tragic death of Sydney Smith Dickens in 1872, Georgina resumed contact with Catherine. She also became a regular visitor to her home in Gloucester Crescent.

Catherine Hogarth Dickens suffered from cancer and on her deathbed she gave her collection of letters from her husband to her daughter, Kate Dickens Perugini: "Give these to the British Museum, that the world may know he loved me once". She died on 22nd November 1879 and is buried in Highgate Cemetery in London.

In her will she bequeathed to her sister, Georgina Hogarth, "my snake ring". Lucinda Hawksley author of Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter (2006): "Perhaps it was an item she knew Georgina admired; on the other hand, there are grounds for believing that the snake emblem was Catherine's poignant comment on how she viewed her younger sister."

Gladys Storey, the author of Dickens and Daughter (1939), has pointed out that it was sometime before the letters from Dickens to Catherine were published: "The letters, together with the locket, were subsequently delivered to the Museum in 1899 by her doctor; with the proviso that they should not be shown for thirty years. Mrs. Perugini later approached the Trustees of the British Museum with the request that the period be extended to after her death, and finally until after the deaths of her brother, Sir Henry F. Dickens, and herself, being the last surviving children of Charles Dickens."

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Dickens , letter to John Forster (12th June, 1858)

Poor Catherine and I are not made for each other, and there is no help for it. It is not only that she makes me uneasy and unhappy, but that I make her so too - and much more so. She is exactly what you know in the way of being amiable and complying, but we are strangely ill-assorted for the bond there is between us. God knows she would have been a thousand times happier if she had married another kind of man, and that her avoidance of this destiny would have been at least equally good for us both. I am often cut to the heart by thinking what a pity it is, for her own sake, that I ever fell in her way; and if I were sick or disabled to-morrow, I know how sorry she would be, and how deeply grieved myself, to think how we had lost each other. But exactly the same incompatibility would arise, the moment I was well again; and nothing on earth could make her understand me, or suit us to each other. Her temperament will not go with mine. It mattered not so much when we had only ourselves to consider, but reasons have been growing since which make it all but hopeless that we should even try to struggle on. What is now befalling me I have seen steadily coming, ever since the days you remember when Mary was born; and I know too well that you cannot, and no one can, help me.

(x) Arthur A. Adrian, Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens Circle (1957)

With Charles back again after his two-week tour, she felt the shadow of his dark moods fall once more. Though she had done her best to reconcile him to Catherine, she was now beginning to agree with him that harmony was impossible. Earlier that month he had unburdened himself to Forster, confessing that with each year the marriage became harder to bear for both Catherine and him. He assumed his share of the blame: "There is plenty of fault on my side... in the way of a thousand uncertainties, caprices, and difficulties of disposition." Again at the end of the month: "Poor Catherine and I are not made for each other, and there is no help for it". What a tragedy that he had ever met her and kept her from marrying "another kind of man"! He knew she would be sympathetic if he were ill, but with his recovery the old barriers would rise between them.... Nothing on earth could make her understand me, or suit us to each other."

As if to underscore the hopelessness of their life together, he made the wall between them tangible in October. From the country retreat he wrote Anne Brown (now Mrs. Cornelius), for many years their trusted servant, instructing her to have his dressing-room converted into a separate bedroom. The opening between it and Catherine's room was to be closed off with a plain white door, with specially built bookshelves in the recess. A small iron bedstead, already ordered for his use, would be delivered before he returned to London. He asked Anne to rive these alterations no publicity, as he preferred not to have them discussed by "comparative strangers".

(2) Gladys Storey , Dickens and Daughter (1939)

Georgina Hogarth and Mamie entirely sided with Dickens. His eldest son and Mrs. Perugini (the other six children, aged from seven to seventeen, were kept in ignorance as to what was going on) acceded to their father's wishes. Mrs. Perugini took her mother's part in-so-far as it was possible for her to do so. But the situation was a difficult one, since Dickens had sternly impressed upon them that "their father's name was their best possession" - which they knew to be true - and he expected them to act accordingly.

When Dickens heard that John Leech had communicated to a mutual friend that "Charley sided with his mother", he wrote to him immediately saying, "you strike me in a tender place and wound me deeply... Charley's living with his mother to take care of her is my idea - not his." Miss Ethel Dickens told the author that her father had a great sense of justice, and she had always understood that, if her grandfather had not arranged for him to reside with his mother, he would have done so of his own accord.

One afternoon, at the commencement of this affair, Mrs. Perugini happened to be passing her parents' bedroom (which stood ajar) when she heard somebody crying. Entering the room, she found her mother seated at the dressing-table in the act of putting on her bonnet, with tears rolling down her cheeks. Inquiring the cause of her distress, Mrs. Dickens-between her sobs - replied :

"Your father has asked me to go and see Ellen Ternan."

"You shall not go!" exclaimed Mrs. Perugini, angrily stamping her foot.

But she went.

In the early stages of their married life Dickens made a compact with his wife that if either of them fell in love with anybody else, they were to tell one another. Such an idea at that period of their lives appeared ludicrous, but Dickens remembered the compact, and had told his wife to call upon the girl with whom he had fallen in love.

(3) Peter Ackroyd , Dickens (1990)

Through the first two and half weeks of May, Forster and Lemon, with Catherine and Mrs Hogarth, tried to draw up a suitable deed of separation which would satisfy all parties without the need to enter a court of law. But Dickens's hopes of keeping the business secret were necessarily misplaced; rumours about the impending separation began to spread and, as is usually the case, rumour begat rumour. That he was having an affair with an actress... and then there were rumours, infinitely more damaging, that he was having an affair with his own sister-in-law. With Georgina Hogarth. That she had given birth to his children. More astonishing still, it seems likely that these rumours about Georgina were in fact started or at least not repudiated by the Hogarths themselves. The point was that Georgina had elected to stay with Dickens and his children even as Catherine was being forced to leave them and, in addition, it seems likely that she knew in advance of Dickens's plans to separate from his wife; his letters to her in the months before these events suggest that she was altogether in his confidence. As a result her mother and her younger sister, Helen, turned upon her; she was still in the confidence of the great novelist, while they were repudiated and despised. Could it be from these feelings of jealousy that so much malice spread? It can happen even in the best of families. "The question was not myself; but others," Dickens later wrote to Macready. "Foremost among them - of all people in the world - Georgina! Mrs Dickens's weakness, and her mother's and her younger sister's wickedness drifted to that, without seeing what they would strike against - though I had warned them in the strongest manner."

Events were now slipping even further out of Dickens's control, and it was at some point in these crucial days that Mrs Hogarth seems to have threatened Dickens with action in the Divorce Court - a very serious step indeed since the Divorce Act of the previous year had decreed that wives could divorce their husbands only on the grounds of incest, bigamy or cruelty. The clear implication here was that Dickens had committed "incest" with Georgina, which was the legal term for sexual relations with a sister-in-law. At Dickens's instigation Forster wrote an urgent letter to Dickens's solicitor, asking for clarification of the new Act; and at the same time, too, Georgina was examined by a doctor and found to be virgo intacta. At this point, it seems, the Hogarths implicitly dropped the threat of court action. Yet the bare facts of the matter can hardly suggest the maelstrom of fury and bitterness into which the family, now divided against itself, had descended. And what of Dickens himself? From the beginning he had tried to keep everything as neat and as ordered as everything else in his life, but it had spiralled out of control. The case for an informal separation had degenerated into a series of formal negotiations which in turn threatened to lead to public exposure of his domestic life; he, the apostle of family harmony, had even been accused of incest with his own wife's sister. He reacted badly to stress and now, during the most anxious days of his life, he ceased to behave in a wholly rational manner.

(4) William Makepeace Thackeray , letter to his mother (May, 1858)

To think of the poor matron after 22 years of marriage going away out of her house! O dear me its a fatal story for our trade... Last week going into the Garrick I heard that Dickens is separated from his wife on account of an intrigue with his sister in law. No says I no such thing - its with an actress - and the other story has not got to Dickens's ears but this has - and he fancies that I am going about abusing him!

(5) Charles Dickens to Angela Burdett-Coutts (9th May, 1858)

You have been too near and dear a friend to me for many years, and I am bound to you by too many ties of grateful and affectionate regard, to admit of my any longer keeping silence to you on a sad domestic topic. I believe you are not quite unprepared for what I am going to say, and will, in the main, have anticipated it.

I believe my marriage has been for years and years as miserable a one as ever was made. I believe that no two people were ever created, with such an impossibility of interest, sympathy, confidence, sentiment, tender union of any kind between them, as there is between my wife and me. It is an immense misfortune to her - it is an immense misfortune to me - but Nature has put an insurmountable barrier between us, which never in this world can be thrown down.

You know me too well to suppose that I have the faintest thought of influencing you on either side. I merely mention a fact which may induce you to pity us both, when I tell you that she is the only person I have ever known with whom I could not get on somehow or other, and in communicating with whom I could not find some way to a kind of interest. You know I have many impulsive faults which often belong to my impulsive way of life and exercise of fancy; but I am very patient and considerate at heart, and would have beaten a path to a better journey's end than we have come to, if I could.

We have been virtually separated for a long time. We must put a wider space between us now, than can be found in one house.

If the children loved her, or ever had loved her, this severance would have been a far easier thing than it is. But she has never attached one of them to herself, never played with them in their infancy, never attracted their confidence as they have grown older, never presented herself before them in the aspect of a mother. I have seen them fall off from her in a natural - not an unnatural - progress of estrangement, and at this moment I believe that Mary and Katey (whose dispositions are of the gentlest and most affectionate conceivable) harden into stone figures of girls when they can be got to go near her, and have their hearts shut up in her presence as if they closed by some horrid spring.

No one can understand this, but Georgina who has seen it grow from year to year, and who is the best, the most unselfish, and the most devoted of human Creatures. Her sister Mary, who died suddenly and who lived with us before her, understood it as well though in the first months of our marriage. It is her misery to live in some fatal atmosphere which slays every one to whom she should be dearest. It is my misery that no one can understand the truth in its full force, or know what a blighted and wasted life my marriage has been.

Forster is trying what he can, to arrange matters with her mother. But I know that the mother herself could not live with her. I am perfectly sure that her younger sister and brother could not live with her. An old servant of ours is the only hope I see, as she took care of her, like a poor child, for sixteen years. But she is married now, and I doubt her being afraid that the companionship would wear her to death. Macready used to get on better with her than anyone else, and sometimes I have a fancy that she may think of him and his sister. To suggest them to her would be to inspire her with an instant determination never to go near them.

In the mean time I have come for a time to the office, to leave her Mother free to do what she can at home, towards the getting of her away to some happier mode of existence if possible. They all know that I will do anything for her comfort, and spend anything upon her.

It is a relief to me to have written this to you. Don't think the worse of me; don't think the worse of her. I am firmly persuaded that it is not within the compass of her character and faculties, to be other than she is. If she had married another sort of man, she might however have done better. I think she has always felt herself at the disadvantage of groping blindly about me and never touching me, and so has fallen into the most miserable weaknesses and jealousies. Her mind has, at times, been certainly confused besides.

(6) Charles Dickens , Household Words (12th June, 1858)

Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it... By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth.

(7) Elizabeth Barrett Browning, diary entry (11th July 1858)

What is this sad story about Dickens and his wife? Incompatibility of temper after twenty-three years of married life? What a plea! Worse than irregularity of the passions it seems to me. Thinking of my own peace and selfish pleasures, too, I would rather be beaten by my husband once a day than lose my child out of the house - yes, indeed... Poor woman! She must suffer bitterly - that is sure.

(8) Lucinda Hawksley , Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter (2006)

For Katey and Mamie, the knowledge that their father was sexually attracted to a girl their own age must have been utterly distasteful. Children are never happy to think about their parents' sex life and, in the nineteenth century, sex was a subject seldom discussed between the generations. The humiliation of their mother would also have been increasingly hard to bear for Katey. In a little over fifteen years, Catherine had given birth to ten children, as well as suffering at least two miscarriages. It is no wonder she did not have the energy of her childfree younger sister; nor that she lost the slim figure she had possessed when Charles married her. Towards the end of their marriage he had often made cruel jokes about her size and stupidity while praising Georgina to the hilt as his helpmeet and saviour. Both Katey and Mamie - by dint of being female - would undoubtedly have cringed at the way their father spoke about their mother and the way he made no secret of preferring the company of her sister, of Ellen and, for that matter, almost any other young attractive woman.

(9) Gladys Storey , Dickens and Daughter (1939)

One afternoon, when Mrs. Perugini was sitting by the bedside of her mother (who knew she was dying), she requested her to go to a drawer and bring her a bundle of letters (there was also a locket containing a likeness of her husband and a lock of his hair) which her daughter placed upon the bed. Tenderly laying her hand upon the treasured missives, Mrs. Dickens said with great earnestness:

"Give these to the British Museum - that the world may know that he loved me once."

Mrs. Perugini promised her mother to do this. (The letters, together with the locket, were subsequently delivered to the Museum in 1899 by her doctor; with the proviso that they should not be shown for thirty years. Mrs. Perugini later approached the Trustees of the British Museum with the request that the period be extended to after her death, and finally until after the deaths of her brother, Sir Henry F. Dickens, and herself, being the last surviving children of Charles Dickens.)

The end came on November 22nd, r879, in the presence of her daughter Kitty, who, whilst brushing her hair in the little dressing-room, was beckoned by the nurse to come. With the brush still in her hand she moved to the bed, when her mother looked at her and smiled.