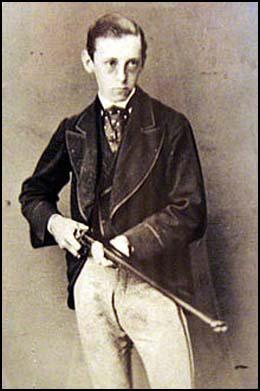

Edward Bulwer Lytton (Plorn) Dickens

Edward Bulwer Lytton (Plorn) Dickens, the last child of Charles Dickens and Catherine Hogarth Dickens, was born on 13th March 1852. He was named after the novelist, Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Dickens told Angela Burdett-Coutts that "on the whole I could have dispensed with him". However, "Plorn" as he was called became the spoilt child of the family. He wrote to a friend that "I begin to count the children incorrectly, they are so many; and to find fresh ones coming down to dinner in a perfect procession and I thought there were no more."

With his brothers, Alfred, Frank and Henry at a boarding school for English boys in Boulogne, Edward was the only child at home with his parents, his aunt, Georgina Hogarth, his sisters, Mamie and Kate, and his brother Charles. Dickens's biographer, Peter Ackroyd has argued that Edward was "amiable, shy, affectionate, but a boy of no real ability and, as it turned out, no real application or energy." Mamie later commented: "These two (Dickens and Edward) were constant companions in those days, and after these walks my father would always have some funny anecdote to tell us.

Edward failed to impress his father when he went to school. As Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "A shy boy with no idea of what he wanted to do in life, he had been taken out of school at fifteen and was sent to an agricultural college in Cirencester." His brother, Alfred , was a manager of a sheep station in New South Wales.

In 1868 Charles Dickens decided to send the sixteen-year-old, to Australia. He wrote to Alfred asking him to help his younger brother. He added that he could ride, do a little carpentering and make a horse shoe but raised doubts about whether he would take to life in the bush. Dickens gave Edward a letter the last time he saw him: "I need not tell you that I love you dearly, and am very, very sorry in my heart to part with you. But this life is half made up of partings, and these pains must be borne." He then urged him to leave behind the lack of "steady, constant purpose" and henceforth "persevere in a thorough determination to do whatever you have to do as well as you can do it". The letter concluded, "I hope you will always be able to say in after life, that you had a kind father".

Henry Fielding Dickens took Edward to Portsmouth. Henry later recalled: "He (Edward) went away, poor dear fellow, as well as could possibly be expected. He was pale, and had been crying, and had broken down in the railway carriage after leaving Higham station; but only for a short time." Dickens told a friend: "Poor Plorn has gone to Australia. It was a hard parting at the last. He seemed to become once more my youngest and favorite little child as the day drew near, and I did not think I could have been so shaken. These are hard, hard things, but they might have to be done without means or influence, and then they would be far harder. God bless him!"

Edward settled at Wilcannia, New South Wales where he became manager of the Momba station. He married Constance Desailly in 1880. After receiving a £800 loan from his brother, Henry , he bought a share in Yanda station near Bourke. He also went into politics and was elected as the member for Wilcannia in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in 1889 and held the seat until defeated by the Labor Party candidate in 1894.

Arthur A. Adrian has argued: "His life in Australia had been marked by business failures, gambling losses, and unpaid debts. Eighteen years earlier his frantic appeals had brought a loan of £800 from Harry, aid which had never been acknowledged. Nor had Plorn ever made any payments on principal and interest. He may have lost the money, it has been conjectured, by gambling in a desperate attempt to bolster up his failing business." Edward admitted that "Sons of great men are not usually as great as their father. You cannot get two Charles Dickens in one generation."

Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens died on 23rd January, 1902.

Primary Sources

(1) Mamie Dickens, Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter (1894)

For many consecutive summers we used to be taken to Broadstairs. This little place became a great favorite with my father. He was always very happy there, and delighted in wandering about the garden of his house, generally accompanied by one or other of his children. In later years, at Boulogne, he would often have his youngest boy, "The Noble Plorn," trotting by his side. These two were constant companions in those days, and after these walks my father would always have some funny anecdote to tell us. And when years later the time came for the boy of his heart to go out into the world, my father, after seeing him off, wrote: "Poor Plorn has gone to Australia. It was a hard parting at the last. He seemed to become once more my youngest and favorite little child as the day drew near, and I did not think I could have been so shaken. These are hard, hard things, but they might have to be done without means or influence, and then they would be far harder. God bless him!"

(2) Arthur A. Adrian, Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens Circle (1957)

On the day of farewell Georgina and Mamie sent Plorn off from Gad's Hill in Harry's company. What happened thereafter was reported to them later. Plorn had broken down briefly in the railway carriage after leaving Higham. He had wept again at Paddington Station on being seen off for Plymouth. But it was Dickens, Harry noted, who had broken down the more painfully, with utter disregard of onlookers. He had met the boys in London and, having had a reminder from Georgina, had supplied Plorn with cigars - a rather odd gift for a sixteen-year-old, unless intended for bestowal on travel acquaintances or possibly on Rusden, the boy's sponsor in Australia." To Dolby, himself a father, Dickens poured out his grief: "When you come (if you ever do) to send your youngest child thousands of miles away for an indefinite time, and have a rush into your soul of all the many fascinations of the last little child you can ever dearly love, you will have a hard experience of this wrenching life".

(3) Claire Tomalin, Dickens: A Life (2011)

In April, Charley formally took over from Wills at All the Year Round. Then, on 2 June, Dickens added a codicil to his will giving Charley the whole of his own share and interest in the magazine, with all its stock and effects. In this way he did the best he could to look after the future of his beloved first-born son, in whom he had once placed such hopes: he would not - could not - now give up on him, in spite of his failures and bankruptcy. Henry continued to do well at Cambridge and could be relied on to make his own way. In May he wrote to his fourth son, Alfred, expressing his "unbounded faith" in his future in Australia, but doubting whether Plorn was taking to life there, and mentioning Sydney's debts: "I fear Sydney is much too far gone for recovery, and I begin to wish that he were honestly dead." Words so chill they are hard to believe, with which Sydney was cast off as Walter had been when he got into debt, and brother Fred when he became too troublesome, and Catherine when she opposed his will. Once Dickens had drawn a line he was pitiless.

The conflicting elements in his character produced many puzzles and surprises. Why was Charley forgiven for failure and restored to favour, Walter and Sydney not? Because Charley was the child of his youth and first success, perhaps. But all his sons baffled him, and their incapacity frightened him: he saw them as a long line of versions of himself that had come out badly. He resented the fact that they had grown up in comfort and with no conception of the poverty lie had worked his way out of, and so he cast them off; yet he was a man whose tenderness of heart showed itself time and time again in his dealings with the poor, the dispossessed, the needy, other people's children.

(4) Kate Dickens Perugini to Edward Dickens (October, 1874)

My dearest Plorn, I have to thank you for a charming letter and a beautiful present. I cannot tell you dear, how very kind and good I think it is of you to make us a wedding gift.... I am quite sure you and Ally will like him, he is so very nice, and good. Henry and he are capital friends, and Frank was constantly with us and I know is very fond of him. My dearest Plorn how very good of you and dear Ally to join us in wishing to help Frank to a new start. I feel quite sure that Frank's future life will repay us for any kindness we can do to him now, at this very moment I expect he is starting. H. like a dear is with him to the last, and as soon as H. himself comes from Liverpool he is coming down here and we shall hear all about the final departure. These goodbyes are so painful! It is better to say how do you do! and I hope dear Plorn we shall have to say that to you before many years. It will be so pleasant to see your nice little old face again and dear Ally too. How much I should like to see him, and his pretty wife and little girl. But I hope they will all come to England some day. Ally's photo is quite imposing I think, and he seems to have more whiskers than all the rest of the Dickens family put together. By the bye, Plorn, how do you get on in that way? Tell me when you next write, also if your dear noble nose is still a little on one side? Perhaps it has gone over to the other, or do you lie flat on your face in order to keep a symmetrical front view? Tell me all particulars, also exactly how tall you are. Mamie and I are still very small. I am afraid we don't grow with years, except in wisdom of course. Henry is not tall, but he is slight & nicely formed and is a very good looking young fellow I think and in his wig, is truly beautiful. You will see the photograph, it is a lovely creature. Frank had always a handsome face and has now, a nice little very light golden moustache, he is going to let his beard grow. Bob is handsome, everyone says. I know his face so well that I don't know whether it is handsome or not, but I am quite sure it is the very best and goodest face in the whole world. Mamie is staying with us which is a great delight to me. She & I are always devoted to one another. She is simply an angel. I wish you could see your present which she has chosen. Now Plorn if you forget to give my dearest love to Ally & Jessie I'll never never never forgive you.

(5) Arthur A. Adrian, Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens Circle (1957)

The next year (1902) brought word of the death of her youngest nephew, Plorn, from whom she had not heard directly since his note of thanks for her wedding gift. His life in Australia had been marked by business failures, gambling losses, and unpaid debts. Eighteen years earlier his frantic appeals had brought a loan of £800 from Harry, aid which had never been acknowledged. Nor had Plorn ever made any payruents on principal and interest. He may have lost the money, it has been conjectured, by gambling in a desperate attempt to bolster up his failing business.