Luke Fildes

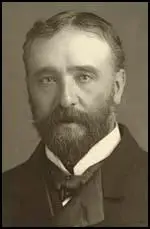

Luke Fildes, the fourth of the ten children of James Fildes and Susanna Fildes, was born on 18th October 1843 at 22 Standish Street, Liverpool. His father mariner and shipping agent. His grandmother, Mary Fildes, was a political activist who was one of the speakers at the Manchester meeting that ended in the Peterloo Massacre. In the 1840s Mary ran the Shrewsbury Arms in Chester and was a leading figure in the Female Chartist movement.

At the age of eleven he went to live with his grandmother. As well as going to school in 1857 he began attending evening classes in art at Chester's Mechanics' Institute. Although Mary Fildes initially disapproved of her grandson studying art, she supported him financially during his studies. Fildes enrolled at Warrington Art School in 1860. There he met the artist Henry Woods (1846–1921), who became a lifelong friend. Fildes won a scholarship to study at the Government Art Training School, South Kensington, and moved to London in October 1863. He also studied at the Royal Academy Schools (1865–6). Fildes met Hubert von Herkomer and Frank Holl. All three men became influenced by the work of Frederick Walker, the leader of the social realist movement in Britain.

Fildes shared his grandmother's concern for the poor and in 1869 joined the staff of the Graphic magazine, an illustrated weekly edited by the social reformer, William Luson Thomas. Fildes shared Thomas' belief in the power of visual images to change public opinion on subjects such as poverty and injustice. Thomas hoped that the images in the magazine would result in individual acts of charity and collective social action.

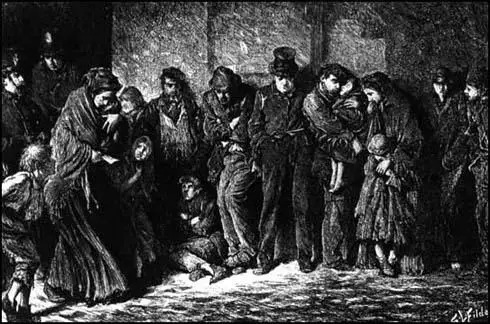

In the first edition of the Graphic magazine that appeared in December 1869, Luke Fildes was asked to provide an illustration to accompany an article on the Houseless Poor Act, a new measure that allowed some of those people out of work shelter for a night in the casual ward of a workhouse. The picture produced by Fildes showed a line of homeless people applying for tickets to stay overnight in the workhouse. Fildes later recalled that the work was based on first-hand experience: "Some few years before, when I first came to London, I was very fond of wandering about, and never shall I forget seeing somewhere near the Portland Road, one snowy winter's night the applicants for admission to a casual ward."

Fildes's engraving, entitled Houseless and Hungry, was seen by John Everett Millais who brought it to the attention of Charles Dickens. Dickens wrote to Fildes: "I see that you are an adept at drawing scamps, send me some specimens of pretty ladies." When he received this pictures he replied: "I can honestly assure you that I entertain the greatest admiration for your remarkable powers."

Dickens now commissioned Fildes to illustrate The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Fildes wrote to Henry Woods: "Congratulate me! I am to do Dickens's story. Just got the letter settling the matter. Going to see Dickens on Saturday... My heart fails me a little for it is the turning point in my career. I shall be judged by this."

The critics liked Fildes's illustrations in Dickens's book and this followed by work from a variety of books and periodicals, including All the Year Round, The Quiver, Once a Week, the Cornhill Magazine, and the Gentleman's Magazine. When Dickens died in 1870 the Graphic published a drawing by Fildes of the novelist's study. The Empty Chair was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1871 and was a popular success as a poignant image of the novelist's death.

Fildes work was seen to be very different from other artists, such as George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight Browne, who had previously illustrated Dickens's novels. As Janet E. Davis has pointed out: "Fildes's illustrative style was influenced by the black and white work of artists such as George John Pinwell, Fred Walker, and particularly John Everett Millais, who worked in a more realist style and prided themselves on drawing directly from nature, breaking with the early Victorian style of illustration represented by George Cruikshank and H. K. Browne. Fildes's illustrations were strong compositions and exhibited his tendency to emphasize the principal foreground figures by drawing them in more detail, and with greater clarity than the background. His ability to use line to describe forms - straight lines for flat surfaces, curving lines for rounded forms - was particularly well suited to the medium of woodcut prints and resulted in clearer, more dynamic illustrations than the more traditional drawing method of cross-hatching for areas of chiaroscuro."

On 15th July, 1874, Fildes married Fanny Woods, the sister of his great friend, Henry Woods. Fanny Fildes was a model for a number of Fildes's paintings besides his portrait of her. She was also an artist and exhibited at the Dudley Gallery and at the Royal Academy. Among their seven children was the microbiologist Sir Paul Fildes (1882–1971).

Fildes turned several of his early engravings were later turned into paintings. This included a version of Houseless and Hungry that he called Applicants to a Casual Ward (1874). Julian Treuherz has pointed out: "Fildes returned to his original studies from models found in the streets, and also made new studies. The composition was changed to give more depth and space, the setting of the painting becoming more detailed. Fildes introduced the lamp, and the posters ironically offering £2 for a missing child, £20 for a missing dog, £50 for a murderer and £100 for a runaway... Nearly all the figures are self-absorbed and downcast eyes, except for the man next to the policeman, the respectable man from the country; new to such a scene, he looks on with horror. His reaction is ours, the spectators."

The Art Journal praised the painting for its "notable realism" but the reviewer in The Times argued that the realism and the subject were not considered as suitable for fine art because of the "unrelieved squalor and hopeless misery and we doubt the justification of inflicting such pain through painting". The Manchester Courier added that it was "repulsive in the extreme and quite belong to the chamber-of-horrors style of art... they simply appal and disgust without doing the slightest good to humanity or making it more merciful."

His biographer, Janet E. Davis, has argued: "Fildes's work as an illustrator continued to influence black and white artists throughout the 1870s and 1880s, and was admired by Vincent Van Gogh. He had questioned prevailing middle-class attitudes about poverty, class, and morality in his social realist work and, through it, challenged contemporary ideas about the definition of high art by combining the large scale of history paintings with a journalistic approach to recording contemporary reality. His paintings paved the way for other realist art, such as that of the Newlyn School, in the late nineteenth century."

Other paintings by Fildes that dealt with social issues included The Return of the Penitent (1876) and The Widower (1876). On seeing the second of these paintings George Augustus Sala wrote: "It touched me very deeply indeed... You bold young geniuses lash in your colour so audaciously that we weak-eyed fogies are puzzled, sometimes, to know whether there is any drawing underneath the paint at all."

In the 1880s Luke Fildes became a portrait painter and soon became one of the most successful artists in England. However, in 1890 Fildes returned to social subjects when he was commissioned by Henry Tate to paint a picture for his new National Gallery of British Art. Fildes decided to paint a picture based on the death of his son called The Doctor. The painting shows a concerned physician watching a dying child. The painting was acclaimed by the critics and became one of the best-selling engravings of the Victorian era. One doctor told his students that "a library of books would not do what this picture has done and will do for the medical profession in making the hearts of our fellow men warm to us with confidence and affection."

Despite the £3,000 Henry Tate paid for The Doctor, Fildes complained that he would have made more money by painting portraits. Julian Treuherz, the author of Hard Times: Social Realism in Victorian Art (1987), has argued: "It is true that Fildes, Holl and Herkomer all abandoned social realism in favour of portraiture in the latter part of their careers. This may not have been because social realism did not sell, but simply that painting portraits was quicker and less demanding. The search for novel subjects, models and locations was troublesome and time-consuming."

After it was finished Fildes returned to painting the rich and famous. Fildes belief in realism sometimes caused him problems with his subjects. Cecil Rhodes was so angry with his portrait he sent Fildes a note with the cheque claiming that "as soon as it arrives I will burn it". Fildes responded by refusing the cheque and keeping the picture.

By 1900 Fildes was the most highly paid portrait painters in England. His painted several members of the royal family including a portrait of Edward VII on his deathbed. Janet E. Davis has argued: "Fildes was a compassionate and caring man, loyal to friends, although liable to disagree strongly with them when their principles or lifestyles did not match up to his standards... Fildes also had a strong sense of humour, which is evident in some of his illustrations and in his correspondence with Henry Woods. He was a loving and affectionate father, anxious for the welfare of his seven children, although regarded by them as authoritarian on occasion."

Luke Fildes, who was knighted in 1906, died at his home, 11 Melbury Road, Kensington, on 27th February 1927. He was buried at Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking.