Adelaide Anne Procter

Adelaide Anne Procter, the eldest daughter and first child of the poet Bryan Waller Procter (1787–1874) and his wife, Ann Skepper Procter (1799–1888), was born on 30th October 1825 at 25 Bedford Square, London. (1)

From 1815 her father contributed poems to many journals using various pen-names but eventually fixing upon Barry Cornwall. He became a close friend of James Leigh Hunt, William Hazlitt, William Wordsworth, Elizabeth Gaskell, Charles Lamb, William Makepeace Thackeray and over the years became acquainted with most of the best writers in London. (2)

According to the lawyer, Henry Crabb Robinson, Bryan Waller Procter had a genius for friendship, being a man of great kindness and generous appreciation, "a man whom everybody loves". (3) Hilaire Belloc pointed out that Adelaide grew up in a household where "everybody of any literary pretension whatever seemed to flow in and out". (4)

Adelaide was close to her father. The literary hostess, Jane Octavia Brookfield, wrote of Bryan Procter's attachment to his "bright, enthusiastic daughter", and of father and daughter "with critical approbation" admiring each other's work. Charles Dickens, a friend of the family, claimed that Adelaide Procter showed an early appreciation of poetry, and also a great facility for learning languages (French, Italian, and German), and for Euclidean geometry, music, and drawing. Nathaniel Parker Willis described her as "a beautiful girl, delicate, gentle, and pensive", looking as if she "knew she was a poet's child". (5) Fanny Kemble agreed that she "looks like a poet's child, and a poet" with a "thoughtful, mournful expression for such a little child". (6)

Frederick Denison Maurice, a Christian Socialist, and supporter of Chartism, was attracted to the educational ideas of Robert Owen. In 1848 Maurice and a small group of tutors at King's College established Queen's College in Harley Street. The first group of students to attend this new training school for teachers included Adelaide Anne Procter, Dorothea Beale, Sophia Jex-Blake and Francis Mary Buss. (7)

Langham Place Group

Adelaide also met Barbara Leigh Smith, an artist who was a great supporter of women's rights. Smith introduced Adelaide to her friends, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies and Bessie Rayner Parkes. She introduced the women to the works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Davies later wrote that the women were the first people "who sympathised with my feelings of resentment at the subjection of women". According to Margaret Forster, the author of Significant Sisters (1984), Davies was especially impressed with Barbara: "Although she was not at all the sort of person who adored anyone... but quickly came to adore Barbara. She even approved of how she dressed, in loose flowing clothes with her long blonde hair flowing down her back. She was, in every sense, a revelation." (8)

In 1857 Adelaide Anne Procter, Barbara Leigh Smith, Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, Louisa Garrett Smith, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn, Sophia Jex-Blake, Alice Westlake,Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett and Emily Faithfull got together to form the Langham Place Group. Davies refused to be secretary because she thought it was prudent to keep her own name "out of sight, to avoid the risk of damaging my work in the education field by its being associated with the agitation for the franchise." Louisa Garrett Smith agreed to take on the role of secretary and be the organisation's figurehead. (9)

These women were therefore "at the core of the emerging mid-Victorian women's movement". (10) The group played an important role in campaigning for women to become doctors. They arranged for Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor, to give a lecture entitled, "Medicine as a Profession for the Ladies". In 1862 they formed a committee to campaign for women's entry for university examinations, initially in support of Elizabeth Garrett, in her application to matriculate at London University. (11)

In March 1858 members of the Langham Place Group were involved in the publication of The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, who like Bodichon, was a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (12)

Society for Promoting the Employment of Women

Adelaide Anne Procter joined together with Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Leigh Smith and Emily Faithfull to establish the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women (SPEW) in June 1859. They enlisted the support of Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, who became the society's first president, and other members of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (13) Another important member was the Christian Socialist and legal scholar, John Westlake. (14)

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women was based initially at 19 Langham Place. They began a law copying office, a school to train women as bookkeepers, clerks, and cashiers, and a register of employment. While such measures could clearly help only a few women of the middling classes, the pioneers regarded their innovations as experiments which prepared the ground for future change. (15)

As Jane Rendall pointed out: "These liberal feminists recognized a potential conflict with orthodox political economy, often invoked against women's work as depressing the wages of men in free competition. Some, like Boucherett, were prepared to face the consequences of a free market in labour. Parkes and others suggested ways in which association and co-operation among women might moderate the harshness of the free market, though some proposals looked more like philanthropy than co-operation." (16) Jessie Boucherett considered Adelaide to be the "animating spirit" of the Society. (17)

The Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women gained support for its efforts from The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (18)

The journal was published monthly and cost 1 shilling. It was used to discuss female employment and equality issues concerning, in particular, manual or intellectual industrial employment, expansion of employment opportunities, and the reform of laws pertaining to the sexes. The offices in Langham Place became a centre for a wide variety of feminist enterprises. These included a women's reading-room and dining club, and offices for the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. (19)

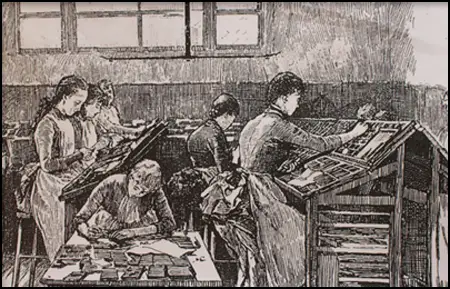

On 25th March 1860, Emily Faithfull established the Victoria Press at Great Coram Street, London. She invested her own capital in the press and had the financial backing of another committee member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. The Victoria Press printed The English Woman's Journal. The press employed at the outset women compositors, despite the trade restrictions practised by men, but the venture was to remain an irritant to many compositors and others in the printing trade. (20) Elizabeth Rayner Parkes wrote in her diary: "So here are women in the trade at last! One dream of my life!" (21)

The business opened on 25th March 1860 with five women apprentices; by October the number had increased to sixteen. This was the first time in England that female compositors had been trained and employed. This aroused a "great deal of public interest, generally favourable, although the women faced a good deal of hostility and even attempts at intimidation from male printers." However, in September 1860 The Times reported that Queen Victoria had given her approval of the establishment of the Victoria Press... for the employment of female compositors." (22)

Adelaide Anne Procter: Poet

Adelaide Procter's first published poem was Ministering Angels, which appeared in Heath's Book of Beauty in 1843. In 1850, Charles Dickens, established the periodical Household Words. As he was a family friend she submitted poems under the pseudonym Mary Berwick, in case he printed them "for papa's sake, and not for their own".Dickens, admired the poems and published them without knowing they were written by Adelaide. It was not until December 1854 that she admitted to being "Mary Berwick". She became Dickens's most published poet, with seventy-three poems published in Household Words and seven in All the Year Round. Dickens wrote that "she was a finely sympathetic woman, with a great accordant heart and a sterling noble nature". (23)

In 1858 a first series of her Legends and Lyrics was published by Bell and Daldy, and was followed in 1861 by a second series. Emma Mason, in her book, Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century (2006), claims that Procter's work often embodies a Victorian aesthetic of sentimentality. (24) In her defence, Gill Gregory, suggests her primarily concerned with the working classes, particularly working-class women, and with "emotions of women antagonists which have not fully found expression". (25)

Pam Hirsch claims that Procter was as popular a woman poet as Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Christina Rossetti. (26) According to English poet and literary critic, Coventry Patmore, the demand for her poetry was greater than for any other English poet with the exception of Alfred Tennyson. Some of her poems were widely sung as hymns in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The most famous of her lyrics was A Lost Chord, set to music by Arthur Sullivan in 1877. Her poetry was translated into German and published in America. Individual poems appeared in the Cornhill Magazine, Good Words, and the The English Woman's Journal. (27)

Early Death

Adelaide Anne Procter showed signs of illness in 1862. Some of her friends suggested that her illness was due to her extensive charity work, which "appears to have unduly taxed her strength". On 3rd February 1864, Procter died aged 38 of tuberculosis, having been bed-ridden for almost a year. The Ilustrated London News reported: "Adelaide Anne Procter, the gifted daughter of a poet, and herself a poetess, who was already achieving a high reputation, has just passed away in the very budding of her literary merit and fame." (28) Her death was described by one newspaper as a "national calamity". (29) Another said she was a "rare and beautiful genius". (30)

The Evening Freeman claimed: "The general public of English readers will regret in the last post a writer whose fascination was candidly and cordially acknowledged by critics of every degree, and deeply felt by thousands of readers; in the pure brightness of whose fancy gentle and simple alike rejoiced; whose pathos touched the heart of young and old; and whose song, in its clear, true tone, was ever audible through the clamour of miner minstrels, and lingered in the memory when more piercing notes had ceased to echo and louder harmonies were stilled." (31)

Bessie Rayner Parkes was with Adelaide Anne Procter when she died. Parkes wrote a letter about this to Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon. "How exquisitely lovely she looked all the week, shrouded in white and sprinkled with flowers, nor how bright and peaceful the day of the funeral was, at the Catholic cemetery at Kensal Green, I cannot describe to you now adequately. It was both a calm and a happy death bed dear Barbara. The suffering was so gallantly even gaily borne; her resignation so perfect. Anything of melancholy had long disappeared... Her own idea of life and death was thoroughly supernatural. I have tried hard to make everybody about us, about Langham Place see and feel this, and not treat it as a dreadful gloomy misfortune. I believe with my whole force of my soul that she is with Jesus, and being with Him is still closely linked up with His interests here. If I had looked at it in the natural way, simply death, removed into an unknown sphere, removed from us, the Church on Earth, the loss would have killed me. But I never could look at it except in the light of her own faith. And I thank God it is so." (32)

Bodichon responded very differently to Parkes' death. "Adelaide's death has come to me like an earthquake. The news of it, even though I knew it would come, shook me from head to foot... Death to me is so very dreadful, and hoping and believing in a future would not make it less so. They who are gone from us here and are death and dumb for us all the years we live - it is very dreadful to me... I feel Adelaide's death is as a light gone from among us, and that though she did not mean as much to my life as she did to yours." (33) Pam Hirsch took the view: "Adelaide's death seemed to emblematise the end of youth and all youth's highest hopes." (34)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Dickens, introduction to Adelaide Anne Procter's Legends and Lyrics (1858)

When she (Adelaide Anne Procter) was quite a young child, she learnt with facility several of the problems of Euclid. As she grew older, she acquired the French, Italian, and German languages... piano-forte... and drawing. But, as soon as she had completely vanquished the difficulties of any one branch of study, it was her way to lose interest in it, and pass to another.

(2) Adelaide Anne Procter, A Lost Chord (1860)

Seated one day at the Organ,

I was weary and ill at ease,

And my fingers wandered idly

Over the noisy keys.I do not know what I was playing,

Or what I was dreaming then ;

But I struck one chord of music,

Like the sound of a great Amen.It flooded the crimson twilight,

Like the close of an Angel's Psalm,

And it lay on my fevered spirit

With a touch of infinite calm.It quieted pain and sorrow,

Like love overcoming strife ;

It seemed the harmonious echo

From our discordant life.It linked all perplexéd meanings

Into one perfect peace,

And trembled away into silence

As if it were loth to cease.I have sought, but I seek it vainly,

That one lost chord divine,

Which came from the soul of the Organ,

And entered into mine.It may be that Death's bright angel

Will speak in that chord again,

It may be that only in Heaven

I shall hear that grand Amen.

(3) Bessie Rayner Parkes, letter to Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (February 1864)

How exquisitely lovely she looked all the week, shrouded in white and sprinkled with flowers, nor how bright and peaceful the day of the funeral was, at the Catholic cemetery at Kensal Green, I cannot describe to you now adequately. It was both a calm and a happy death bed dear Barbara. The suffering was so gallantly even gaily borne; her resignation so perfect. Anything of melancholy had long disappeared... Her own idea of life and death was thoroughly supernatural. I have tried hard to make everybody about us, about Langham Place see and feel this, and not treat it as a dreadful gloomy misfortune. I believe with my whole force of my soul that she is with Jesus, and being with Him is still closely linked up with His interests here. If I had looked at it in the natural way, simply death, removed into an unknown sphere, removed from us, the Church on Earth, the loss would have killed me. But I never could look at it except in the light of her own faith. And I thank God it is so.

(4) Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, letter to Bessie Rayner Parkes (February 1864)

Adelaide's death has come to me like an earthquake. The news of it, even though I knew it would come, shook me from head to foot... Death to me is so very dreadful, and hoping and believing in a future would not make it less so. They who are gone from us here and are death and dumb for us all the years we live - it is very dreadful to me... I feel Adelaide's death is as a light gone from among us, and that though she did not mean as much to my life as she did to yours.

(5) The Ilustrated London News (13th February 1864)

Adelaide Anne Procter, the gifted daughter of a poet, and herself a poetess, who was already achieving a high reputation, has just passed away in the very budding of her literary merit and fame. This lamented lady died on the 2 nd instance at her father's house, 32, Weymouth Street, Portland Place… She first became known to the public by her productions, Lyrics and Legends, and A Chaplet of Verse. These and her subsequent publications had placed her among the most popular lady poets of the day.

(6) Dublin Weekly Nation (13th February 1864)

Not a few readers of the Nation, we are sure, will grieve to learn that Adelaide Anne Procter is no more, called away thus in the prime of womenhood, and in the full maturity of her rare and beautiful genius – while the echoes, too, of her sweetest and holiest songs still "vibrate in the memory" it seems as if the summons must have been a strangely sudden one…

How short the time seems since we noticed with genuine welcome and admiration in these columns the exquisite Chaplet of Verses by which the lost poet is now, perhaps, best known on the side of the Channel! Her Legends and Lyrics have made her name familiar wherever English literature finds readers. Each series of these charming poems has run through many editions, both in England and America.

(7) The Evening Freeman (20th February 1864)

The religious no less than the literary world has good cause to lament the loss of Miss Adelaide Anne Procter, whose death, in London, we shortly announced some few days since.

The general public of English readers will regret in the last post a writer whose fascination was candidly and cordially acknowledged by critics of every degree, and deeply felt by thousands of readers; in the pure brightness of whose fancy gentle and simple alike rejoiced; whose pathos touched the heart of young and old; and whose song, in its clear, true tone, was ever audible through the clamour of miner minstrels, and lingered in the memory when more piercing notes had ceased to echo and louder harmonies were stilled.