John Westlake

John Westlake, was born at Lostwithiel, Cornwall, on 4th February 1828, the only son of John Westlake, a woolstapler, and his wife, Eleanora, daughter of George Burgess, rector of Atherington, north Devon. In his early years he was taught by his parents, and in 1835 he went to Lostwithiel grammar school. (1)

In April 1842 the family moved to Cambridge, where Westlake was privately tutored by, among others, the Revd John W. Colenso, who had been greatly influenced by the teaching of Frederick Denison Maurice, who believed in a united Christian Church that transcended the differences between individuals and races as he had put forward in The Kingdom of Christ (1838). (2)

The book became the theological basis of Christian Socialism. In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. Christian Socialists promoted the cooperative ideas of Robert Owen and suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society. (3)

On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (4)

John Westlake and Christian Socialism

Westlake became converted to Christian Socialism before he went to Trinity College, University of Cambridge, and graduated BA in January 1850. He was elected a fellow of his college in October 1851 and took his MA in 1853. He had moved to London in 1852 with his mother and only sister, Mary Elizabeth, his father having died in 1849. There he joined Lincoln's Inn, and he was called to the bar in 1854. In the same year his sister died of cholera, aged twenty-seven. (5)

In 1853 Maurice was dismissed from his Professorship at King's College because of his leadership in the Christian Socialist Movement, and because of the supposed unorthodoxy of his Theological Essays (1853). (6) In February 1854 Frederick Denison Maurice drew up a scheme for a Working Men's College. On 30th October 1854 Maurice delivered an inaugural address at St. Martin's Hall and the college started with over 140 students, of whom were working men, in a building in Red Lion Square. (7)

Maurice became principal and guest lecturers at the college included John Westlake (mathematics), Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. As his biographer, Nathan Wells, pointed out: "This was a typically selfless gesture by Westlake - in so aiding his fellow human beings he was risking his career at the bar (to which he had only just been called), as Maurice and his associates were at the time popularly viewed as dangerous cranks, infected with the socialism of Louis Blanc, whose activities in the revolutionary year of 1848 were still so repugnant to the English. Westlake was also a strong supporter of the enfranchisement of women, and strongly in favour of proportional representation." (8)

John Westlake became friends with Sir Thomas Hare (1806-1891) Hare was a legal scholar who devised a system of proportional representation of all classes and opinions in the United Kingdom, including minorities, in the House of Commons and other electoral assemblies. (9) Hare's suggested reforms were supported by Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill. Fawcett thought Hare's scheme offered "the only remedy against the great danger of an oppression of minorities". (10)

Alice Westlake and Women's Suffrage

On 13th October 1864 he married Thomas Hare's daughter, Alice Hare. There were no children of the marriage. Alice Westlake was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and in May 1865, was one of those women in London who formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (11)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (12)

On 18th March, 1865, Alice Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (13) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (14)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Barbara Bodichon (artist), Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (15)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (16)

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. (17) Ann Dingsdale points out: "The annual subscription was half a crown. Questions for debate were issued four times a year and members might speak at meetings or submit written answers. Corresponding members submitted papers that were discussed by those who could attend (and who paid a further half-crown for that privilege). By conducting its debates in a private arena, with apparently nominated discussions, the society encouraged a frank exchange of views." (18)

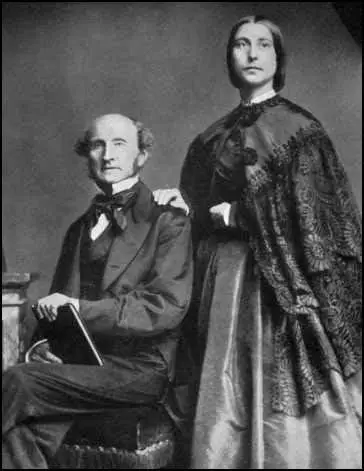

Helen Taylor was an important member of the Kensington Society because she was the step-daughter of John Stuart Mill, a philosopher who fully supported women's suffrage. In an article published in 1861 he argued: "In the preceding argument for universal, but graduated suffrage I have taken no account of difference of sex. I consider it to be as entirely irrelevant to political rights, as differences in height, or in the colour of the hair. All human beings have the same interest in good government; the welfare of all is alike affected by it, and they have equal need of a voice in it to secure their share of its benefits. If there be any difference women require it more than men, since being physically weaker, they are more dependent on law and society for protection." (19)

John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. The Kensington Society saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (20)

Helen Taylor replied the same day: "It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights." (21)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Elizabeth Garrett and Jessie Boucherett, had already started collecting signatures. (22) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (23)

On 20th May 1867, Mill made a speech in the House of Commons where he proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (24)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (25)

On 7th June, 1867 Barbara Bodichon was ill and so Elizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, escorted the great scroll to Westminster Hall and gave their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill, said, "Ah! this I can brandish with effect." (26)

Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." (27)

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (28)

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to dissolve the organisation early in 1868 and to establish the London Society for Women's Suffrage with the sole purpose of campaigning for women's suffrage. (29) Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. (33) Alice Westlake was a member of these organisations. (30)

John Westlake and Women's Rights

John Westlake took a keen interest in women's rights and a supporter of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science and the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women (SPEW). (31) They enlisted the support of Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, who became the society's first president. SPEW was based initially at 19 Langham Place. They began a law copying office, a school to train women as bookkeepers, clerks, and cashiers, and a register of employment. While such measures could clearly help only a few women of the middling classes, the pioneers regarded their innovations as experiments which prepared the ground for future change. (32)

Westlake was also a member of the Enfranchisement of Women Committee that was formed in 1866. The society attracted 88 members including Emily Davies, Lydia Becker, Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon, Helen Blackburn, Clementia Taylor, Alice Westlake and Peter Alfred Taylor. Louisa Garrett Smith was honorary secretary. It had "for its object the abolition of the legal disability which at present disqualifies women as such from voting for Members of Parliament." It hoped to achieve this aim by presenting further petitions to parliament in order to demonstrate the earnestness of women in this matter." (33)

John Westlake was an equity lawyer, with an emphasis on land law, but his practice consisted largely of cases with an international flavour, and he built up a good practice at the privy council. However, his obituarist in The Times commented, "Not possessing the mental agility, pliancy, adaptability or temperament of the born advocate, he was unsuitable for the ordinary run of cases." (34)

In 1885 Westlake was elected Liberal Party MP for the Romford division of Essex, beating the Conservative Party candidate, James Theobald, by only 64 votes. In the House of Commons he supported women's suffrage. However, the home-rule crisis which soon followed saw Westlake nail his colours to the Unionist mast, and in July 1886 he stood for re-election as a Liberal Unionist, but lost his seat. Six years later he contested St Austell as a Liberal Unionist. (35)

During the campaign John Westlake stated why she was a supporter of the Liberal Party: "Improvement in human affairs can only be attained – nay, deterioration can only be prevented – through the unremitting exertions of the best, the most clear-sighted, and the most hopeful of the community. But such exertions, applied fearlessly in doing always the work which lies nearest may be treated to bring about a future both better than, and different from either the present or any state of things that can be imagined. I am a Liberal, because, in addition to concurrence in particular opinions, I believe that the Liberal Party includes more of the men, and works more in the spirit, thus indicated, than the Conservative Party." (36)

On 14th April 1913, John Westlake died at the age of 85 at his London residence, the River House, on the Chelsea Embankment. He suffered a stroke, following a heart attack. (37)

Primary Sources

(1) John Westlake, St. Austell Star (12th September 1890)

Improvement in human affairs can only be attained – nay, deterioration can only be prevented – through the unremitting exertions of the best, the most clear-sighted, and the most hopeful of the community. But such exertions, applied fearlessly in doing always the work which lies nearest may be treated to bring about a future both better than, and different from either the present or any state of things that can be imagined. I am a Liberal, because, in addition to concurrence in particular opinions, I believe that the Liberal Party includes more of the men, and works more in the spirit, thus indicated, than the Conservative Party.

(2) David Simkin, Family History Research (20th August 2023)

The 1901 Census recorded John and Alice Westlake at No.3 Chelsea Embankment (also known as ‘The River House’). On the census return, 73-year-old John Westlake is described as a “Barrister (K.C.)” and “Professor at Cambridge University” (between 1888 and 1908, John Westlake was Whewell Professor of International Law at the University of Cambridge). No profession is given for 59-year-old Alice Westlake. The Westlakes were employing 5 domestic servants at their Chelsea home. At the time of the 1901 Census, Alice’s brother Alfred Richard Hare, his wife Alice, and their children, were visiting the Westlakes at ‘The River House’.

Ten years’ later John and Alice Westlake were still living at No.3 Chelsea Embankment. On the 1911 Census form, 83-year-old John Westlake declared that he was a Barrister, K.C. but was no longer practising. No personal occupation is given for Alice Westlake, his 69-year-old wife. Five domestic servants were still employed at The River House on Chelsea Embankment. On the night of Sunday, 2nd April, 1911, the Westlakes had three guests – their 23-year-old niece, Eva Hare, the daughter of Alice’s younger brother Alfred Hare (1849-1903), and the artist couple, Charles Adrian Scott Stokes, A.R.A., and his wife Marianne Stokes.

Two years after the 1911 Census, on 14th April 1913, Alice’s husband of 48 years, John Westlake of The River House, Chelsea Embankment and of Lincoln’s Inn, Middlesex, died at the age of 85. He left effects valued at £8,324 15s. 5d. to his widow. The 1921 Census records Alice Westlake, a 79-year-old widow, at No. 3 Chelsea Embankment. She was attended by two professional nurses and 3 domestic servants.

(3) Nathan Wells, John Westlake: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2008)

Westlake, John (1828–1913), jurist, was born at Lostwithiel, Cornwall, on 4 February 1828, the only son of John Westlake (d. 1849), a woolstapler, and his wife, Eleanora (d. 1866), daughter of George Burgess, rector of Atherington, north Devon. In his early years he was taught by his parents, and in 1835 he went to Lostwithiel grammar school. In April 1842 the family moved to Cambridge, where Westlake was privately tutored by, among others, the Revd J. W. Colenso (subsequently bishop of Natal) and Dr W. H. Bateson (who was later appointed master of St John's College, Cambridge).

Westlake went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in Michaelmas term 1846, was scholar in Easter term 1848, and graduated BA in January 1850 as sixth wrangler and sixth classic. He was elected a fellow of his college in October 1851 and took his MA in 1853. He had moved to London in 1852 with his mother and only sister, Mary Elizabeth, his father having died in 1849. There he joined Lincoln's Inn, and he was called to the bar in 1854. In the same year his sister died of cholera, aged twenty-seven. On 13 October 1864 he married Alice, daughter of Thomas Hare, advocate of proportional representation. Her elder sister, Marion Andrews, was the novelist and historian who wrote under the name Christopher Hare. There were no children of the marriage....

In 1874 Westlake was appointed QC and elected a bencher of Lincoln's Inn. Three years later he was made an honorary doctor of laws by Edinburgh University. In 1878 his home town of Lostwithiel elected him its recorder, and in 1880 the second edition of his Treatise appeared, having effectively been rewritten since 1858.

In 1885 Westlake was elected Liberal MP for the Romford division of Essex, beating the Conservative candidate by only 64 votes. However, the home-rule crisis which soon followed saw Westlake nail his colours to the Unionist mast, and in July 1886 he stood for re-election as a Liberal Unionist, but lost his seat. Six years later he unsuccessfully contested St Austell as a Unionist.

Westlake gave up practice at the bar in 1888, when he was appointed to the Whewell chair of international law at the University of Cambridge. His connections with international law before the appointment had not been confined to his legal practice and his Treatise; among other notable contributions he had, in 1869, co-founded Le Revue de Droit International et de Legislation Comparée, the first periodical of international law; and in 1873 he co-founded L'Institut de Droit International, of which he was president in 1895, and permanent honorary president from 1910.

During his time at Cambridge, Westlake published his most important works on public international law: Chapters on the Principles of International Law (1894), and International Law, Part 1: Peace (1904), and Part 2: War (1907). It was also at this time that he sat as one of the British members of the International Court of Arbitration under the Hague Convention, between 1900 and 1906.

Westlake resigned the Whewell chair in 1908, and during his later years he largely withdrew from public life owing to his increasing deafness, though he was by no means a recluse. Besides those honours already mentioned he received many more in recognition of his juristic standing: an honorary DCL degree from the University of Oxford (1908); an honorary doctorate of law from the Free University of Brussels (1909); an honorary fellowship of Trinity College, Cambridge (1910); membership of the Academie Royal of Brussels; the Italian order of the Crown; and the Japanese order of the Rising Sun.

Westlake died on 14 April 1913 at his London residence, the River House, on the Chelsea Embankment. He suffered a stroke, following a heart attack. His ashes were interred at Zennor churchyard in Cornwall, under a celtic cross....

On social and political questions, Westlake was a "convinced and unflinching liberal", with a hatred of all kinds of oppression or injustice, though his strong support for the rights of the individual stemmed perhaps from an idealistically or even naïvely benevolent view of human nature.

Westlake was a founder in 1854, with F. D. Maurice and others, of the Working Men's College in Great Ormond Street, London, where he taught mathematics. This was a typically selfless gesture by Westlake - in so aiding his fellow human beings he was risking his career at the bar (to which he had only just been called), as Maurice and his associates were at the time popularly viewed as dangerous cranks, infected with the socialism of Louis Blanc, whose activities in the revolutionary year of 1848 were still so repugnant to the English. Westlake was also a strong supporter of the enfranchisement of women, and strongly in favour of proportional representation.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)