Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women

Jessie Boucherett was inspired to help women find employment after reading an article entitled "On Female Industry" by Harriet Martineau in the Edinburgh Review about the subject. In the article Martineau suggested: "Out of six millions of women above twenty years of age, in Great Britian, exclusive of Ireland, and of course of the Colonies, no less than half are industrial in their mode of life. More than a third, more than two millions, are independent in their industry, are self-supporting, like men." (1)

It has been argued that the effect of this article on Boucherett was life-changing. She wrote later that "at once [she] resolved to make it the business of her life to remedy or at least to alleviate the evil by helping self-dependent women, not with gifts of money, but with encouragement and training for employments suited to their capabilities." (2)

In 1857 Barbara Leigh Smith, Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, Louisa Garrett Smith, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn, Sophia Jex-Blake, Alice Westlake, Adelaide Anne Procter, Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett and Emily Faithfull got together to form the Langham Place Group. Davies refused to be secretary because she thought it was prudent to keep her own name "out of sight, to avoid the risk of damaging my work in the education field by its being associated with the agitation for the franchise." Louisa Garrett Smith agreed to take on the role of secretary and be the organisation's figurehead. (3)

Jessie Boucherett suggested that the group should help promote women's employment. As a result the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW) was established in June 1859 in London. They enlisted the support of Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, who became the society's first president, and other members of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (4) Another important member was the Christian Socialist and legal scholar, John Westlake. (5)

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women was based initially at 19 Langham Place. They began a law copying office, a school to train women as bookkeepers, clerks, and cashiers, and a register of employment. While such measures could clearly help only a few women of the middling classes, the pioneers regarded their innovations as experiments which prepared the ground for future change. (6)

After a visit to the London office Emily Davies established the Northumberland and Durham Branch of the SPEW. However, not all the members of the Langham Place Group were in total agreement about the employment of women in industry. Elizabeth Rayner Parkes condemned the work of married women outside the home, though Boucherett and Faithfull argued that "every woman should be free to support herself by the use of whatever faculties God has given her, without obstruction by prejudice or legislation". (7)

As Jane Rendall pointed out: "These liberal feminists recognized a potential conflict with orthodox political economy, often invoked against women's work as depressing the wages of men in free competition. Some, like Boucherett, were prepared to face the consequences of a free market in labour. Parkes and others suggested ways in which association and co-operation among women might moderate the harshness of the free market, though some proposals looked more like philanthropy than co-operation." (8)

The work of the Langham Place group was given added publicity by the success of two papers given at the conference of the Social Science Association held in Bradford in October 1859. Elizabeth Rayner Parkes read a paper, to which Barbara Leigh Smith contributed, on "The Market for Educated Female Labour" and Jessie Boucherett delivered "The Industrial Employments of Women". (9) Boucherett wrote to Smith claiming: "The whole kingdom is ringing with our Bradford Paper, and subscriptions pouring in at the EWJ (English Woman's Journal) office... What a crown to our long struggle begun 10 years ago.... It is a long struggle which is beginning to tell; and the having an organisation in which to receive the Public Interest." (10)

Harriet Martineau wrote an article about Parkes's speech in The Daily News. "Miss Parkes's paper was abundantly clear and definite. She tells us the truth that a multitude of the daughters of middle-class men are neither educated nor provided for like their brothers; and that if they do not marry, they must work (unprepared by education as they are) or starve. The terms demanded on behalf of women are that parents shall either educate their daughters so as to fit them for independent industry; or lay by a provision for them; or insure their own lives for the benefit of their daughters in the day which will make them fatherless. This is very simple and clear. It is also very interesting; and, as a natural consequence, we hear of sympathy, in the form of advice and suggestions, in all directions; and of various establishments, existing or proposed, with more or less of the charitable element involved for the relief and aid of industrial women of the middle class. (11)

On 1st October 1860 Jessie Boucherett made a speech in Glasgow: "She dealt with three major areas: Jessie Boucherett's work in training young women to take situations as cashiers and clerks, Isa Craig's work in training women as telegraph clerks, and Maria Rye's law copying office where women earned a living by making accurate copies of legal documents." In just over a year SPEW managed to find permanent jobs for up to seventy-five women a year and temporary jobs for up to a hundred. (12)

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women gained support for its efforts from The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (13)

The journal was published monthly and cost 1 shilling. It was used to discuss female employment and equality issues concerning, in particular, manual or intellectual industrial employment, expansion of employment opportunities, and the reform of laws pertaining to the sexes. The offices in Langham Place became a centre for a wide variety of feminist enterprises. These included a women's reading-room and dining club, and offices for the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. (14)

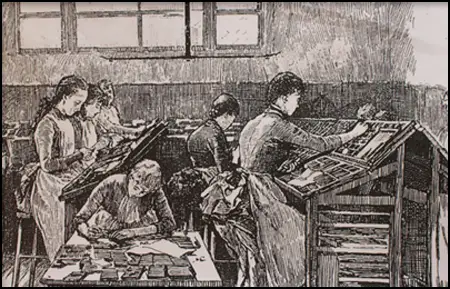

On 25th March 1860, Emily Faithfull established the Victoria Press at Great Coram Street, London. She invested her own capital in the press and had the financial backing of another committee member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. The Victoria Press printed The English Woman's Journal. The press employed at the outset women compositors, despite the trade restrictions practised by men, but the venture was to remain an irritant to many compositors and others in the printing trade. (15) Elizabeth Rayner Parkes wrote in her diary: "They will employ at least 6 girls; so here are women in the trade at last! One dream of my life!" (16)

In 1926 it was renamed the Society for Promoting the Training of Women. It changed its name again in 2014, becoming Futures for Women. It still operates today, as registered charity number 313700 and registered company number 0013103. (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Harriet Martineau, The Daily News (17th November, 1859)

For a good many years now the subject of the independent industry of women in Great Britain has come up at shorter intervals, and with a more peremptory demand on the attention of society. From the day when the Song of the Shirt appeared there could be no doubt that the industrial condition of women would occupy attention as we see it doing now. The founding of the Governesses' Benevolent Institution, the controversies about factory employment for women, the movement in favour of women and watchwork, the opening of a few Schools of Design to women, and of an annual exhibition of pictures by them, and the successful footing they have established in various department of Art, have all pointed to the awakening of that wide interest in the subject which we witness now. The Edinburgh Review of last April contained a full narrative of the actual state of female industry in this country; and at the Social Science Meeting at Bradford, a paper read by Miss Parkes excited so much interest that the discussion has been kept up, and does not seem likely to drop at present.

Discussion about what? This is an important thing to know in a case in which so much sentiment is involved, and so much prejudice, and so much sense, and so much goodwill. What is the precise mischief to be taken in hand and what is to be done to cure it?

Miss Parkes's paper was abundantly clear and definite. She tells us the truth that a multitude of the daughters of middle-class men are neither educated nor provided for like their brothers; and that if they do not marry, they must work (unprepared by education as they are) or starve. The terms demanded on behalf of women are that parents shall either educate their daughters so as to fit them for independent industry; or lay by a provision for them; or insure their own lives for the benefit of their daughters in the day which will make them fatherless. This is very simple and clear. It is also very interesting; and, as a natural consequence, we hear of sympathy, in the form of advice and suggestions, in all directions; and of various establishments, existing or proposed, with more or less of the charitable element involved for the relief and aid of industrial women of the middle class.

Under such circumstances there must be a melancholy waste of effort, unless we ascertain betimes what it is that is wanted, and how the want may be met, with something like concert and business-like faculty. Looking at the matter from a practical point of view, the conditions of the case seem to be these.

It is supposed by persons whose attention has not been particularly called to the subject, that the women of Great Britain are maintained by their fathers, husbands, or brothers. It was once so; and careless people are unaware that we have long outgrown the fit of that theory of female maintenance. It has been out at elbows at least since the war which ended with Waterloo. From the last Census Report we learn how things were eight years ago-before the last war which has much increased the tendency of women to maintain themselves. In Great Britain, without Ireland, there were in 1851 six millions of women above twenty years of age. More than half of these work for their living. Does this surprise our readers? If it never occurred to them before, they will be still further impressed by the fact that two millions of women, out of the six millions, are independent in their industry-are selfsupporting, like men. So far is the theory of women being maintained by their male relatives from being now true. But how do these women work? and how far do they succeed in maintaining themselves? for it is universally understood that women are paid less than men for the same kind and degree of work. Society has been a good deal surprised by the disclosures in the Divorce Court of the amount of effectual female industry, proved by applications for protection of earnings from bad husbands. That women should maintain themselves and their children seems a matter of course when they are unhappily married; and the revelation has caused a good many people to perceive that there is a good deal going on in middle-class life which they were unaware of. It may strike some observers that the matter has far outgrown the scope and powers of charitable societies, and that the independent industry of Englishwomen has become a fact which must be

recognised by the law, and which must itself essentially modify middle-class education throughout the kingdom.

(2) Jessie Boucherett, letter to Barbara Leigh Smith (17th November 1859)

The whole kingdom is ringing with our Bradford Paper, and subscriptions pouring in at the EWJ office... What a crown to our long struggle begun 10 years ago.... It is a long struggle which is beginning to tell; and the having an organisation in which to receive the Public Interest.