Octavia Hill

Octavia Hill, the eighth daughter (and ninth child) of James Hill, corn merchant and his third wife, Caroline Southwood Hill, was born on . Octavia's father was an early supporter of Robert Owen and his socialist utopianism. However, in 1840 he went bankrupt and after a nervous breakdown virtually disappeared from her life. Octavia's mother had to turn to her father, Dr Thomas Southwood Smith, for financial support and he became in many respects a surrogate father to her children. Southwood Smith, who was a dedicated utilitarian, and a follower of Jeremy Bentham, had spent his life campaigning on issues such as child labour to housing conditions of the working classes.

Octavia Hill and her sisters were educated entirely at home by their mother. In 1852 Caroline Southwood Hill moved to Russell Place, Holborn. She had been offered the job of manager and bookkeeper of the Ladies Guild, a co-operative crafts workshop nearby. Now aged fourteen, Octavia became her mother's assistant. This involved visiting the homes of the toymakers. During this period she heard the lectures of Frederick Denison Maurice and was deeply influenced by his Christian Socialism. Her biographer, Gillian Darley, commented: "Brought up a Unitarian, her mother left Octavia's religious allegiances deliberately untouched. In 1857, as a result of her friendship with F. D. Maurice and his circle, she was baptized and then confirmed into the Church of England; but she remained notably undogmatic. She regarded faith as a personal matter and never intruded upon the religious observance of the tenants she was to acquire - many of whom were Irish Catholics."

In 1853 Octavia Hill met John Ruskin who, along with Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes, was part of Maurice's Christian Socialist circle. Ruskin also taught at the Working Men's College that had been founded by Maurice. Ruskin employed Octavia as a copyist. In 1856 Maurice offered her a job as secretary to the women's classes for a salary of £26 per year. The college aimed to educate women "for occupations wherein they could be helpful to the less fortunate members of their own sex". Octavia also joined the campaign of Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon for a married women's property act.

Octavia Hill also read the work of Henry Mayhew, a journalist working for the Morning Chronicle. Another journalist, Douglas Jerrold wrote to a friend in February, 1850: "Do you read the Morning Chronicle? Do you devour those marvellous revelations of the inferno of misery, of wretchedness, that is smouldering under our feet? We live in a mockery of Christianity that, with the thought of its hypocrisy, makes me sick. We know nothing of this terrible life that is about us - us, in our smug respectability. To read of the sufferings of one class, and the avarice, the tyranny, the pocket cannibalism of the other, makes one almost wonder that the world should go on. And when we see the spires of pleasant churches pointing to Heaven, and are told - paying thousands to Bishops for the glad intelligence - that we are Christians!. The cant of this country is enough to poison the atmosphere."

Mayhew's articles concerned the life of the working class living in London started her thinking about what she could do to relieve their suffering. However, conservative-minded people condemned this call for charity. The Economist attacked the publication of Mayhew's work because it believed was "unthinkingly increasing the enormous funds already profusely destined to charitable purposes, adding to the number of virtual paupers, and encouraging a reliance on public sympathy for help instead on self-exertion."

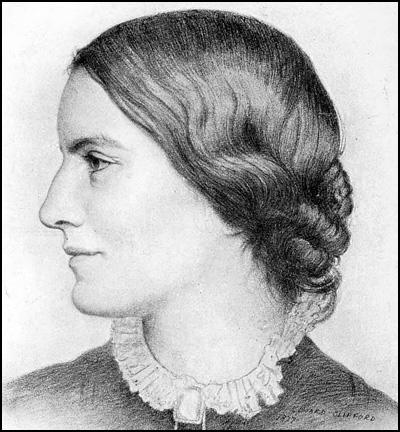

According to Gillian Darley: "By 1859 Hill's daily routine of copying in Dulwich Art Gallery or the National Gallery, followed by many more hours spent teaching, had become punishing. Even F. D. Maurice told her that trying to do without rest was very self-willed but she took no notice. A tiny woman (all the family were diminutive) with a heavy-browed head and great dark eyes, her indomitable personality was already fixed. Eventually her family forced her to go to Normandy on holiday, but a dangerous pattern of working until she collapsed was established which would periodically interrupt her work over the coming years."

in 1864 Ruskin's father died, leaving a substantial sum to his only son. He agreed to invest some of his inheritance in Octavia Hill's long-held dream, to establish improved housing for "my friends among the poor". She purchased a terrace of artisans' cottages just off Marylebone High Street, London, and a short walk from Regent's Park. The premises were transformed by cleaning, ventilation, clearance of the drains, repairs, and redecoration. Octavia also recruited a team of women that included Henrietta Barnett, Catherine Potter and Emma Cons to help her with this venture. She later argued that the most important aspect of her system was the weekly visit to collect rent. This allowed her and her colleagues to check upon every detail of the premises and to broaden their contact with the tenants, especially the children. They also tried to find local and regular employment for the tenants. Norman Mackenzie has described the women as "welfare workers and moral guardians of their tenants".

Octavia Hill had been influenced by the ideas expressed by Samuel Smiles in his book, Self-Help (1859). This resulted in her developing strong opinions about helping the poor. She argued: "We have made many mistakes with our alms, eaten out the heart of the independent, bolstered up the drunkard in his indulgence, subsidised wages, discouraged thrift, assumed that many of the most ordinary wants of a working man’s family must be met by our wretched and intermittent doles."

Tristram Hunt has pointed out: "Octavia always had an admirably broad conception of the lives of the inner-city poor and closely connected cultural philanthropy to social reform. It wasn’t enough to collect the rent and fix the gutters. Her growing acreage of housing estates in Lambeth, Walworth, Deptford and Notting Hill (some 3,000 tenants by the mid-1870s) were hubs of creativity, with panels by the artist Walter Crane, music lessons, cultural outings and Gilbert & Sullivan performances."

Octavia Hill became romantically attached to Edward Bond, a wealthy young man who was interested in her new housing project. Beatrice Webb later recalled: "I remember her well in the zenith of her fame... At that time she was constantly attended by Edward Bond. Alas! for we poor women! Even our strong minds do not save us from tender feelings. Companionship, which meant to him intellectual and moral enlightenment, meant to her 'Love'. This, one fatal day, she told him. Let us draw the curtain tenderly before that scene and inquire no further." His rejection of her led to Octavia suffering a nervous breakdown. Webb added: "She left England for two years' ill health. She came back a changed woman.... She is still a great force in the world of philanthropic action, and as a great leader of woman's work she assuredly takes the first place. But she might have been more, if she had lived with her peers and accepted her sorrow as a great discipline." On her return to England she went to live in a cottage at Crockham Hill, outside Edenbridge, with her recently recruited companion, Harriot Yorke.

In 1883 Octavia Hill published Homes of the London Poor: She argued that the building of good new homes was not the answer: "The people’s homes are bad, partly because they are badly built and arranged; they are tenfold worse because the tenants’ habits and lives are what they are. Transplant them tomorrow to healthy and commodious homes, and they would pollute and destroy them. There needs, and will need for some time, a reformatory work which will demand that loving zeal of individuals which cannot be had for money, and cannot be legislated for by Parliament. The heart of the English nation will supply it - individual, reverent, firm, and wise. It may and should be organised, but cannot be created."

In 1884 Octavia Hill was asked by the ecclesiastical commissioners, to take on the management of certain properties, initially in Deptford and Southwark. Gradually they handed over more and more housing to her management and, in particular, a large area of housing in Walworth in London. She was consulted on the rebuilding of the estate and argued successfully for the involvement of the tenants in the process.

Octavia Hill was considered to be an expert problems. In 1884 Sir Charles Dilke invited her to be a member of the royal commission on housing which he was to chair but the home secretary, Sir William Harcourt, vetoed her. There was a cabinet discussion in which William Gladstone supported her candidacy. Hill would have been the first woman member of a royal commission. However, it was eventually decided to withdraw the offer and instead she became a witness before the royal commission.

Beatrice Webb met Octavia Hill at the home of Henrietta Barnett in 1886: "The form of her head and features, and the expression of the eyes and mouth, show the attractiveness of mental power. A peculiar charm in her smile. We talked on Artisans' Dwellings. I asked her whether she thought it necessary to keep accurate descriptions of the tenants. No, she did not see the use of it... She objected that there was already too much windy talk. What you wanted was action... I felt penitent for my presumption, but not convinced."

In 1889 Octavia Hill became actively involved with the Women's University Settlement, in Southwark. At first she had been prejudiced against the whole scheme. E. Moberly Bell, the author of Octavia Hill (1942), has argued that "she believed so passionately in family life, that a collection of women, living together without family ties or domestic duties, seemed to her unnatural, if not positively undesirable." However, after spending time with the women she remarked: "They are all very refined, highly cultivated... and very young. They are so sweet and humble and keen to learn about things out of the ordinary line of experience."

In 1905 Octavia she joined the royal commission for the Poor Law, with Charles Booth, Beatrice Webb and George Lansbury. The historian, Tristram Hunt, has pointed out: "She was adamant that a distant, Whitehall-run welfare state could never provide such intimacy and personal care. Octavia was dead against free school meals, council housing and a universal old-age pension, with its nefarious attempt to equalise income, and to get rid of charity, and to substitute a rate distributed as of right".

Her biographer, Gillian Darley has argued that Octavia Hill was very much a figure of the 19th century: "Despite the transformation of nineteenth-century philanthropy into twentieth-century social service which was taking place around her, Octavia Hill remained opposed to state or municipal action for welfare. She argued against old-age pensions; as she also opposed parliamentary votes for women, largely on the grounds that women were unfit to determine matters of international policy, defence, and national budgets. She was an enthusiastic supporter of women's involvement in politics at a local, suitably domestic, level. She was visionary in her attempt to bring self-respect to those who had long since lost it, and inspired in the choices and manner of campaigning to improve the lives of the impoverished."

Octavia Hill died of cancer on at her home, 190 Marylebone Road, London.

Primary Sources

(1) Octavia Hill, Homes of the London Poor (1883)

IT is clear to those who are watching the work closely, and must even be apparent to those less conversant with the subject, that a great and growing conviction is abroad that our charitable efforts need concentrating, systematising, and uniting. There are many signs that this conviction is bearing practical fruit. All the thirty Poor-Law districts into which London is divided are now provided with committees for organising charitable relief. The formation of these committees has led gentlemen specially interested in the subject to come forward in various parts of London as candidates for the office of Guardians; several such candidates have been elected in St. George’s, Kensington, Marylebone, and other parishes. Nor is the movement confined to London. Charity Organisation Societies, or others of a kindred nature, have been established in most of the large towns of England and Scotland. Conversation, newspapers, conferences, all bear witness how very generally it is now recognised that something ought to be done to improve our system of charitable relief some co-operation secured between Poor-Law and charity, and some efficient means adopted to render alms less pauperising than they have hitherto been. It is becoming clear to the public that there is a right and a wrong, a wise and an unwise charity. Those who have the interests of the poor at heart are learning, more and more, to consult experienced people before taking any direct steps towards trying to help those who apply to them for aid; those who wish to give money are beginning to entrust it to enlightened committees, instead of endeavouring to distribute it themselves.

It becomes almost needless now to enlarge on the evils of “overlapping,” - that is, of various charitable agencies covering the same ground whilst ignorant of each other’s proceedings; or to dwell on the cruelty of the utter want of system which has hitherto prevailed - to point to poor families assisted by three or four agencies at times when they needed help least, and others neglected by all at times when they needed it most. It would not be difficult to give examples of these evils, and to show that they are inseparable from the condition of large towns wherever nothing is done to secure unity of action amongst those who are trying to assist the poor. Much has been done. The evils of overlapping, on the one hand, and of neglect on the other, are being swept away wherever organisation committees, with their machinery for thorough investigation, and relief societies with their power to assist, are in existence. By means of this system of inquiry into the merits of cases a great degree of uniformity in dealing with them is secured; no relief is given without due consideration, no poor person who chooses to apply can fail to have a hearing for his or her case, and similar needs will meet with a similar response. All this is no small gain. But now a new danger seems to be arising; a danger lest, rushing from one extreme to another, we should leave to committees, with their systems of rules, the whole work of charity, and deprive this great organising movement of all aid from what I may call the personal element. The value of this element seems to me to be inestimable. Charity owes all its graciousness to the sense of its coming from a real friend. We want to bring the rich and poor, the educated and uneducated, more and more into direct communication. We want to enlist the thought, knowledge, sympathy, foresight, and gentleness of the educated in the service of the poor, and must beware of raising up barriers of committees between those who should meet face to face. There is beyond all doubt in almost every town a great amount of volunteer work to be had, which, were it organised and concentrated, would achieve infinitely more than its best efforts can now accomplish. There is always, however, a difficulty in calculating to any great extent on volunteer work, inasmuch as it is apt to be disconnected, desultory, and untrained.

(2) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (28th May, 1885)

Mr Barnett told me much about Octavia Hill. How, when he met her as a young curate just come to London, she had opened the whole world to him. A cultivated mind, susceptible to art, with a deep enthusiasm and faith, and a love of power. This she undoubtedly has and shows it in her age in a despotic temper... I remember her well in the zenith of her fame; some 14 years ago. I remember her dining with us in Prince's Gate, I remember thinking her a sort of ideal of the attraction of woman's power. At that time she was constantly attended by Edward Bond. Alas! for we poor women! Even our strong minds do not save us from tender feelings. Companionship, which meant to him intellectual and moral enlightenment, meant to her "Love". This, one fatal day, she told him. Let us draw the curtain tenderly before that scene and inquire no further. She left England for two years' ill health. She came back a changed woman.... She is still a great force in the world of philanthropic action, and as a great leader of woman's work she assuredly takes the first place. But she might have been more, if she had lived with her peers and accepted her sorrow as a great discipline.