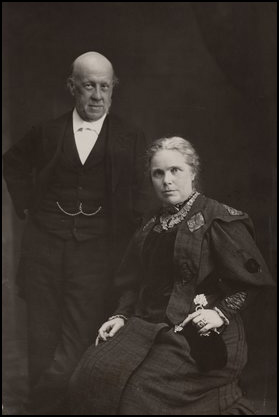

Henrietta Barnett

Henrietta Octavia Weston, the daughter of Alexander William Rowland, whose family fortune derived from Rowland's Macassar Oil Company, and Henrietta Monica Margaretta Ditges, was born in Clapham, London, on 4th May 1851. Her mother died shortly after giving birth to Henrietta.

According to Henrietta's biographer, Seth Koven: "Her formal education consisted of several terms spent at a boarding-school in Dover run by the Haddon sisters, disciples and sisters-in-law of the controversial aural surgeon and social and moral philosopher James Hinton. Given Hinton's and the Haddons' commitment to social altruism it is not surprising that Henrietta first demonstrated compassionate interest in the lives of poor children during her student days."

After the death of her father in 1869 she devoted herself to helping the housing reformer Octavia Hill conduct her charity work in the parish of St Mary's Church, Bryanston Square, London. This brought her into contact with Samuel Augustus Barnett, who was working as a curate at the church under William Henry Fremantle. Barnett later told Beatrice Potter: "Mr Barnett told me much about Octavia Hill. How, when he met her as a young curate just come to London, she had opened the whole world to him. A cultivated mind, susceptible to art, with a deep enthusiasm and faith, and a love of power. This she undoubtedly has and shows it in her age in a despotic temper... I remember her well in the zenith of her fame; some 14 years ago."

On 28th January, 1873, Henrietta married Barnett. Soon afterwards they moved to St Jude's, a parish in Whitechapel. Inspired by the teachings of Frederick Denison Maurice on Christian Socialism, they campaigned against the 1834 Poor Law and advocated what they called "practical socialism". This included a "combination of individual initiative and self-improvement with municipal and state support intended to address specific material needs". They also promoted the aesthetic theories of John Ruskin, and argued that "pictures … could take the place of parables".

Henrietta Barnett became very involved into parish work on behalf of women and children, and gathered a circle of devoted women workers around her. In 1875 she was the first nominated woman guardian, and the following year became school manager of the district schools at Forest Gate. Henrietta, who supported women's suffrage, did considerable amount of "rescue work" with female prostitutes. In 1876 she joined forces with Jane Nassau Senior to form the Metropolitan Association for the Befriending of Young Servants. The organisation aimed to prevent girls from becoming prostitutes, criminals or alcoholics, and provide a steady supply of domestic servants. In 1877, Henrietta established The Children's Fresh Air Mission (Off to the Country). The charity’s aim was to take children from London’s slums away to the seaside for holidays in the fresh air and country surroundings.

Seth Koven has argued that while living in Whitechapel: "Barnett developed an extensive network of clubs and classes to address not only the spiritual but the intellectual and recreative needs of his parishioners. The unpopularity of these ventures encouraged him to think of an alternative non-parochial institutional framework for his work." Barnett was deeply influenced by the pamphlet about slum life The Bitter Cry of Outcast London (1883), written by Andrew Mearns, a Congregationalist clergyman.

In 1884 an article by Samuel Augustus Barnett in the Nineteenth Century Magazine suggested the idea of university settlements. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University could work among, and improve the lives of the poor during their holidays. According to Barnett, the role of the students was "to learn as much as to teach; to receive as much to give". This article resulted in the formation of the University Settlements Association.

Later that year Henrietta and Samuel Barnett established Toynbee Hall, Britain's first university settlement. Most residents held down jobs in the City, or were doing vocational training, and so gave up their weekends and evenings to do relief work. This work ranged from visiting the poor and providing free legal aid to running clubs for boys and holding University Extension lectures and debates; the work was not just about helping people practically, it was also about giving them the kinds of things that people in richer areas took for granted, such as the opportunity to continue their education past the school leaving age. As Seth Koven has pointed out: "Settlements, as first envisioned by the Barnetts, were residential colonies of university men in the slums intended to serve both as centres of education, recreation, and community life for the local poor and as outposts for social work, social scientific investigation, and cross-class friendships between élites and their poor neighbours."

Toynbee Hall served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London. Other individuals who worked at Toynbee Hall include Richard Tawney, Clement Attlee, Alfred Milner, William Beveridge, Hubert Llewellyn-Smith and Robert Morant. Other visitors included Guglielmo Marconi who held one of his earliest experiments in radio there, and Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, was so impressed by the mixing and working together of so many people from different nations that it inspired him to establish the games. Georges Clemenceau visited Toynbee Hall in 1884 and claimed that Barnett was one of the "three really great men" he had met in England.

Octavia Hill, was one of those who did not support the idea of Toynbee Hall. According to Seth Koven: "Octavia Hill, his erstwhile mentor, was so disturbed by what she viewed as Barnett's lax churchmanship that she supported a rival plan undertaken on an explicitly religious basis by the high-church party of Keble College, the Oxford House settlement in Bethnal Green."

Henrietta and Samuel stayed with Beatrice Potter in August 1887. In her diary she wrote: "Visit of three days from the Barnetts, which has confirmed my friendship with them. Mr Barnett distinguished for unself-consciousness, humility and faith. Intellectually he is suggestive, with a sort of moral insight almost like that of a woman. And in another respect he is like a strong woman; he is much more anxious that human nature should feel rightly than that they should think truly, being is more important with him than doing... He was very sympathetic about my work and anxious to be helpful. But evidently he foresaw in it dangers to my character, and it was curious to watch the minister's anxiety about the morale of his friend creep out in all kinds of hints.... He told his wife that I reminded him of Octavia Hill, and as he described Miss Hill's life as one of isolation from superiors and from inferiors, it is clear what rocks he saw ahead."

Beatrice also had strong opinions about Henrietta Barnett: "Mrs Barnett is an active-minded, true and warm-hearted woman. She is conceited. She would be objectionably conceited if it were not for her genuine belief in her husband's superiority... But the good in Mrs Barnett predominates... Her personal aim in life is to raise womanhood to its rightful position; as equal, though unlike, to manhood. The crusade she has undertaken is the fight against impurity as the main factor in debasing women from a status of independence to one of physical dependence. The common opinion that a woman is a nonentity unless joined to a man, she resents as a blasphemy. Like all crusaders, she is bigoted and does not recognize all the facts that tell against her faith. I told her that the only way in which we can convince the world of our power is to show it! And for that it will be needful for women with strong natures to remain celibate, so that the special force of womanhood, motherly feeling, may be forced into public work."

Christopher J. Morley has pointed out: "He (Samuel Augustus Barnett) used music, nonbiblical readings and art to teach those with no education or religious leanings.... Barnett wrote frequently to the press about the conditions in the East End, among his many complaints and suggestions were that street lighting and sanitation should be improved, the poor should treat their womenfolk better and that women should be stopped from stripping to the waist for fights. He also wanted the slaughterhouses removed because of the brutalizing effect it was having on the locals health and morals."

Samuel and Henrietta Barnett had a very happy marriage. She later recalled: "His (Samuel Barnett) temper was naturally of the sweetest, yet he was often surprisingly censorious. His sympathy was both imaginative and subtle, and yet he would harden his heart against the most piteous evidences of poverty, if his economic principles were involved. His generosity in big matters was sometimes reckless, and yet his parsimony in small ones could be both comic and annoying. His patience was part of his religious dependence on God, and yet it was united to restless ruthless energy for reform. His trust in human nature was all-embracing, yet no one investigated the statements of applicants more searchingly." Beatrice Webb saw the Barnetts as "an early example of a new type of human personality, in after years not uncommon; a double-star-personality, the light of the one being indistinguishable from that of the other".

Henrietta and Samuel Barnett set out their ideas in the book, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888). The couple described in detail the poverty they had witnessed in Whitechapel. They concluded the problem was being caused by low wages: "The body's needs are the most exacting; they make themselves felt with daily recurring persistency, and, while they remain unsatisfied, it is hard to give time or thought to the mental needs or the spiritual requirements; but if our nation is to be wise and righteous, as well as healthy and strong, they must be considered. A fair wage must allow a man, not only to adequately feed himself and his family, but also to provide the means of mental cultivation and spiritual development."

The authors rejected the idea that alcohol consumption was the main cause of poverty: "The teetotallers would reply that drink was the cause, but against this sweeping assertion I should like to give my testimony, and it has been my privilege to live in close friendship and neighbourhood of the working classes for nearly half my life. Much has been said about the drinking habits of the poor, and the rich have too often sheltered themselves from the recognition of the duties which their wealth has imposed on them, by the declaration that the poor are unhelpable while they drink as they do. But the working classes, as a rule, do not drink. There are, undoubtedly, thousands of men, and, alas! unhappy women too, who seek the pleasure, or the oblivion, to be obtained by alcohol; but drunkenness is not the rule among the working classes, and, while honouring the work of the teetotallers, who give themselves up to the reclamation of the drunken, I cannot agree with them in their answer to the question. Drink is not the main cause why the national defence to be found in robust health is in such a defective condition."

The Barnett's were concerned that low wages was forcing people to resort to criminal activity. They also warned about the dangers of revolution: "By the growing animosity of the poor against the rich. Goodwill among men is a source of prosperity as well as of peace. Those who are thus bound together consider one another's interests, and put the good of the whole before the good of a class. Among large classes of the poor animosity is slowly taking the place of good-will, the rich are held to be of another nation, the theft of a lady's diamonds is not always condemned as the theft of a poor man's money."

The authors of Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform advised that Christian Socialists should help the poor to form trade unions. They were especially concerned about those employed as dockers: "It would be wise to promote the organisation of un-skilled labour. The mass of applicants last winter belonged to this class, and in one report it is distinctly said that the greater number were born within the demoralising influence of the intermittent and irregular employment given by the Dock Companies, and who have never been able to rise above their circumstances... If, by some encouragement, these men could be induced to form a union, and if by some pressure the Docks could be induced to employ a regular gang, much would be gained. The very organisation would be a lesson to these men in self-restraint and in fellowship. The substitution of regular hands at the Docks for those who now, by waiting and scrambling, get a daily ticket would give to a large number of men the help of settled employment and take away the dependence on chance which makes many careless."

In 1888 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr visited Toynbee Hall. Addams later wrote: "It is a community for University men who live there, have their recreation and clubs and society all among the poor people, yet in the same style they would live in their own circle. It is so free from professional doing good, so unaffectedly sincere and so productive of good results in its classes and libraries so that it seems perfectly ideal." The women were so impressed with what they saw that the returned to the United States and established a similar project, Hull House, in Chicago. The Settlement Movement grew rapidly both in Britain, the United States and the rest of the world. The settlements and social action centres work together through the International Federation of Settlements. Henrietta Barnett also helped establish the Women's University Settlement in Southwark.

Samuel Augustus Barnett resigned St Jude's in 1893 to serve as a canon of Bristol. However, he continued to work as Warden of Toynbee Hall until 1906 when he took up his post as canon of Westminster. The Barnetts were also strong supporter of the Workers' Educational Association, old-age pensions, and labour farm colonies and helped to establish the Whitechapel Gallery.

In 1903 Henrietta Barnett joined forces with Raymond Unwin, Barry Parker and Edwin Lutyens to create the Hampstead Garden Suburb. According to her biographer, Seth Koven: "She embarked on her last and most ambitious project, which dominated the final decades of her life: rescuing 80 acres of Hampstead Heath for public enjoyment and creating the Hampstead Garden Suburb.... Collaborating with the pioneer socialist architects of the Letchworth Garden City, Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker, she created a blueprint for a new kind of organic community consisting of young and old, able-bodied and infirm, rich and poor, married and unmarried. While the largest homes of wealthy residents were placed far from the modest cottages designed for artisans Henrietta hoped that residents of the suburb would be bound together by shared religious, social, educational, and recreational spaces. To this end she successfully advocated the erection of an Anglican church and a nonconformist chapel, along with a purpose-built clubhouse for artisans and their families; the institute, designed by Edwin Lutyens, served as the suburb's focal point for educational, cultural, and civic activity. Henrietta balanced her unwavering commitment to the mutual advantages of relationships between the classes with a staunch belief in the ineradicability of class differences."

Samuel Augustus Barnett died at 69 Kings Esplanade, Hove, on 17th June 1913. Henrietta continued to campaign for the causes she believed in. In the introduction to a new edition of Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1915) she argued: "It is satisfactory that dock labour is organised, that dock directors employ more permanent hands, that workmen are eligible as guardians, that houses have been built fit for habitation, that free libraries, open spaces, and baths have been opened, that the poor-law administration has been made more human, that public opinion against impurity is strengthened, that some of the restrictions imposed by a narrow code on children's education have been removed, that twenty thousand or thirty thousand children spend their holidays in the country, that the status of young servants has been raised, that the People's Palace and polytechnics have been provided, that universal pensions and agricultural training farms are within the range of practical politics, that the offer of the best - the best pictures, the best music - to all is not so unusual, that the entertainment of the poor as equals is not so uncommon, and that in London, in British great towns, in America, and on the Continent University settlements have been started. It is most satisfactory that town councils have been roused to a sense of their powers, and have been made to feel that their reason of being is not political but social, that their duty is not to protect the pockets of the rich but to save the people."

Barnett then went onto argue: "But it is disappointing to reflect how little all these improvements mean: how poor the poor remain, how inadequate are the average wages to meet the needs of life, how vast is the body of labour still unorganised, how low is the standard of health in East London compared with that of West London, how altogether below the requirement is the provision of libraries, baths, and open spaces. It is disappointing that emotion still governs methods of relief, that the rich give to relieve their own feelings rather than to relieve the poor, that the busy and kindly start new charities rather than work with others; that the absenteeism of those who might be channels of civilising influences is still the rule; that it remains true to say that the poor die before their time, suffer unduly for want of air, space, and water, and have not the happiness which comes from calm and knowledge. It is disappointing that so little has been done to advance higher education."

Henrietta Barnett was appointed CBE in 1917 and DBE in 1924. She published the two volume Canon Barnett: His Life Work and Friends in 1918. She also wrote Matters that Matter (1930), a collection of autobiographical essays on various topics. Seth Koven points out: "Henrietta Barnett valued highly motherhood and women's distinct moral gifts as peacemakers capable of defusing class war. Having no children of her own she was legal guardian of both her badly brain-damaged elder sister, Fanny, who shared her home for fifty-eight years, and of Dorothy Woods, the Barnetts' beloved adopted ward. From the 1890s Marion Paterson (whom Henrietta had first met in 1876) was her constant assistant, nurse, secretary, confidante, and companion."

Henrietta Barnett died at her home on 10th June 1936. She was buried at St Helen's Church in Hangleton, alongside her husband.

Primary Sources

(1) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (29th August, 1887)

Visit of three days from the Barnetts, which has confirmed my friendship with them. Mr Barnett distinguished for unself-consciousness, humility and faith. Intellectually he is suggestive, with a sort of moral insight almost like that of a woman. And in another respect he is like a strong woman; he is much more anxious that human nature should feel rightly than that they should think truly, being is more important with him than doing... He was very sympathetic about my work and anxious to be helpful. But evidently he foresaw in it dangers to my character, and it was curious to watch the minister's anxiety about the morale of his friend creep out in all kinds of hints. He held up as a moral scarecrow the "Oxford Don", the man or woman without human ties, and with no care for the details of life. He told his wife that I reminded him of Octavia Hill, and as he described Miss Hill's life as one of isolation from superiors and from inferiors, it is clear what rocks he saw ahead....

Mrs Barnett is an active-minded, true and warm-hearted woman. She is conceited. She would be objectionably conceited if it were not for her genuine belief in her husband's superiority... But the good in Mrs Barnett predominates... Her personal aim in life is to raise womanhood to its rightful position; as equal, though unlike, to manhood. The crusade she has undertaken is the fight against impurity as the main factor in debasing women from a status of independence to one of physical dependence. The common opinion that a woman is a nonentity unless joined to a man, she resents as a "blasphemy". Like all crusaders, she is bigoted and does not recognize all the facts that tell against her faith. I told her that the only way in which we can convince the world of our power is to show it! And for that it will be needful for women with strong natures to remain celibate, so that the special force of womanhood, motherly feeling, may be forced into public work.

(2) Samuel Barnett and Henrietta Barnett, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888)

It is useless to imagine that the nation is wealthier because in one column of the newspaper we read an account of a sumptuous ball or of the luxury of a City dinner, if in another column there is a story of death from starvation. It is folly, and worse than folly, to say that our nation is religious because we meet her thousands streaming out of the fashionable churches, so long as workhouse schools and institutions are the only homes open to her orphan children and homeless waifs. The nation does not consist of one class only; the nation is the whole, the wealthy and the wise, the poor and the ignorant. Statistics, however flattering, do not tell the whole truth about increased national prosperity, or about progress in development, if there is a pauper class constantly increasing, or a criminal class gaining its recruits from the victims of poverty.

The nation, like the individual, is set in the midst of many and great dangers, and, after the need of education and religion has been allowed, it will be agreed that all other defences are vain if it be impossible for the men and women and children of our vast city population to reach the normal standard of robustness. The question then arises. Why cannot and does not each man, woman, and child attain to the normal standard of robustness?

The teetotallers would reply that drink was the cause, but against this sweeping assertion I should like to give my testimony, and it has been my privilege to live in close friendship and neighbourhood of the working classes for nearly half my life. Much has been said about the drinking habits of the poor, and the rich have too often sheltered themselves from the recognition of the duties which their wealth has imposed on them, by the declaration that the poor are unhelpable while they drink as they do. But the working classes, as a rule, do not drink. There are, undoubtedly, thousands of men, and, alas! unhappy women too, who seek the pleasure, or the oblivion, to be obtained by alcohol; but drunkenness is not the rule among the working classes, and, while honouring the work of the teetotallers, who give themselves up to the reclamation of the drunken, I cannot agree with them in their answer to the question. Drink is not the main cause why the national defence to be found in robust health is in such a defective condition.

Land reformers, socialists, co-operators, democrats would, in their turn, each provide an answer to our question; but, if examined, the root of each would be the same - in one word, it is Poverty, and this means scarcity of food.

Let us now go into the kitchen and try and provide, with such knowledge as dietetic science has given us, for a healthily hungry family of eight children and father and mother. We must calculate that the man requires 20 oz. of solid food per day, i.e. 16 oz. of carbonaceous or strength-giving food and 4 oz. of nitrogenous or flesh-forming food. (The army regulations allow 25 oz. a day, and our soldiers are recently declared on high authority to be underfed.) The woman should eat 12 oz. of carbonaceous and 3 oz. of nitrogenous food; though if she is doing much rough, hard work, such as all the cooking, cleaning, washing of a family of eight children necessitate, she would probably need another ounce per day of the flesh-repairing food. For the children, whose ages may vary from four to thirteen, it would be as well to estimate that they would each require 8 oz. of carbonaceous and 2 oz. of nitrogenous food per day: in all, 92 oz. of carbonaceous and 28 oz. of nitrogenous foods per day.

For the breakfast of the family we will provide oatmeal porridge with a pennyworth of treacle and another penny-worth of tinned milk. For dinner they can have Irish stew, with 1 lb. of meat among the ten, a pennyworth of rice, and an addition of two pennyworth of bread to obtain the necessary quantity of strength-giving nutriment. For tea we can manage coffee and bread, but with no butter, and not even sugar for the children; and yet, simple fare as this is, it will have cost 2s. 5d. to feed the whole family, and to obtain for them a sufficient quantity of strength-giving food; and even at this expenditure they have not been able to get that amount of nitrogenous food which is necessary for the maintenance of robust health.

(3) Samuel Barnett and Henrietta Barnett, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888)

Take Mrs. Marshall's family and circumstances. Mrs. Marshall is, to all intents and purposes, a widow, her husband being in an asylum. She herself is a superior woman, tall and handsome, and with clean dapper ways and a slight hardness of manner that comes from bitter disappointment and hopeless struggling. She has four children, two of whom have been taken by the Poor Law authorities into their district schools - a better plan than giving outdoor relief, but, at the same time, one that has the disadvantage of removing the little ones from the home influence of a very good mother.

Mrs. Marshall herself, after vainly trying to get work, was taken as a scrubber at a public institution, where she earns 9s. a week and her dinner. She works from six in the morning till five at night, and then returns to her fireless, cheerless room to find her two children back from school and ready for their chief meal ; for during her absence their breakfast and dinner can only have consisted of bread and cold scraps. We will not dwell on the hardship of having to turn to and light the fire, tidy the room, and prepare the meal after having already done ten hours' scrubbing or washing....

The body's needs are the most exacting; they make themselves felt with daily recurring persistency, and, while they remain unsatisfied, it is hard to give time or thought to the mental needs or the spiritual requirements; but if our nation is to be wise and righteous, as well as healthy and strong, they must be considered. A fair wage must allow a man, not only to adequately feed himself and his family, but also to provide the means of mental cultivation and spiritual development. Indeed, some humanitarians assert that it should be sufficient to give him a home wherein he may rest from noise, with books, pictures, and society; and there are those who go so far as to suggest that it should be sufficient to enable him to learn the larger lessons which travellers gain from other nations, as well as the teaching which the great dumb teachers wait to impart to those with ears to hear of fraternity, purity, and eternal hope.

Why is it that our wage-earners cannot get this ? Why is it that, as we indulge in such dreams, they sound impossible and almost impracticable, though no reader of this review will add undesirable? Is it because our nation has not fought ignorance with pointed weapons, and by its knights of proved prowess and valour? Or is it because our rulers have not recognised the greed of certain classes or individuals as a national evil, and struggled against it with the strength of unity? It cannot be the want of money in our land which causes so many to be half-fed, and cry silently from want of strength to make a noise. As we stand at Hyde Park Comer, or wander in among the miles of streets of gentlemen's residences in the West End, our hearts are gladdened at the sight of the wealth that is in our land; but they would be glad with a deeper gladness if Wilkins was not getting slowly brutalised by his struggle, if there were a chance of Alice and Johnnie Marshall growing up as Nature meant them to grow, or if clever Mrs. Stoneman's patient efforts could be crowned with success. Money in plenty is in our midst, but cruel, blinding Poverty keeps her company, and our nation cannot boast herself of her wealth while half her people are but partly fed, and too poor to use their minds or to aspire after holiness...

Some economists will reply that these sad conditions are but the result of our freedom; that the boasted liberty in our land must result in the few strong making themselves stronger, and in the many weak suffering from their weakness. But is this necessarily so? Is this the only result to be expected from human beings having the power to act as they please? Are not love, goodwill, and social instincts as truly parts of human character as greed, selfishness, and sulkiness; and may we not believe that human nature is great enough to care to use its freedom for the good of all? Men have done noble things to obtain this freedom. They have loved her with the ardour of a lover's love, with the patience of a silver wedded life; and now that they have her, is she only to be used to injure the weak, and to make life cruel and almost impossible to the large majority? What is the right use of freedom? The ancient answer was, To love God. And can we love God whom we have not seen when we love not our brother whom we have seen?

(4) Samuel Barnett and Henrietta Barnett, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888)

Poverty in London is increasing both relatively and actually. Relative poverty may be lightly considered, but it breeds trouble as rapidly as actual poverty. The family which has an income sufficient to support life on oatmeal will not grow in goodwill when they know that daily meat and holidays are spoken of as necessaries for other workers and children. Education and the spread of literature have raised the standard of living, and they who cannot provide boots for their children, nor sufficient fresh air, nor clean clothes, nor means of pleasure, feel themselves to be poor, and have the hopelessness which is the curse of poverty as selfishness is the curse of wealth.

Poverty, however, in East London is increasing actually. It is increased (1) by the number of incapables: broken men, who by their misfortunes or their vices have fallen out of regular work and who are drawn to East London because chance work is more plentiful, company more possible, and life more enlivened by excitement. (2) By the deterioration of the physique of those born in close rooms, brought up in narrow streets, and early made familiar with vice. It was noticed that among the crowds who applied for relief there were few who seemed healthy or were strongly grown. In Whitechapel the foreman of those employed in the streets reported that the majority had not the stamina to make even a good scavenger.' (3) By the disrepute into which saving is fallen. Partly because happiness (as the majority count happiness) seems to be beyond their reach, partly because the teaching of the example of the well-to-do is enjoy yourselves, and partly because "the saving man" seems bad company, unsocial and selfish; the fact remains that few take the trouble to save — only units out of the thousands of applicants had shown any signs of thrift. (4) By the growing animosity of the poor against the rich. Goodwill among men is a source of prosperity as well as of peace. Those who are thus bound together consider one another's interests, and put the good of the whole before the good of a class. Among large classes of the poor animosity is slowly taking the place of good-will, the rich are held to be of another nation, the theft of a lady's diamonds is not always condemned as the theft of a poor man's

money.

(5) Samuel Barnett and Henrietta Barnett, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888)

It would be wise to promote the organisation of un-skilled labour. The mass of applicants last winter belonged to this class, and in one report it is distinctly said that the greater number were born within the demoralising influence of the intermittent and irregular employment given by the Dock Companies, and who have never been able to rise above their circumstances... If, by some encouragement, these men could be induced to form a union, and if by some pressure the Docks could be induced to employ a regular gang, much would be gained. The very organisation would be a lesson to these men in self-restraint and in fellowship. The substitution of regular hands at the Docks for those who now, by waiting and scrambling, get a daily ticket would give to a large number of men the help of settled employment and take away the dependence on chance which makes many careless.... A possible loss of profit is not comparable to an actual loss of life, and the labourers do lose life and more than life that the dividend or salaries may be increased.

(6) Henrietta Barnett, introduction to the new edition of Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1915)

It is difficult to say whether the reading of essays which hold the hopes of twenty years ago arouses more of satisfaction or of disappointment. It is satisfactory that dock labour is organised, that dock directors employ more permanent hands, that workmen are eligible as guardians, that houses have been built fit for habitation, that free libraries, open spaces, and baths have been opened, that the poor-law administration has been made more human, that public opinion against impurity is strengthened, that some of the restrictions imposed by a narrow code on children's education have been removed, that twenty thousand or thirty thousand children spend their holidays in the country, that the status of young servants has been raised, that the People's Palace and polytechnics have been provided, that universal pensions and agricultural training farms are within the range of practical politics, that the offer of the best - the best pictures, the best music - to all is not so unusual, that the entertainment of the poor as equals is not so uncommon, and that in London, in British great towns, in America, and on the Continent University settlements have been started.

It is most satisfactory that town councils have been roused to a sense of their powers, and have been made to feel that their reason of being is not political but social, that their duty is not to protect the pockets of the rich but to save the people.

But it is disappointing to reflect how little all these improvements mean: how poor the poor remain, how inadequate are the average wages to meet the needs of life, how vast is the body of labour still unorganised, how low is the standard of health in East London compared with that of West London, how altogether below the requirement is the provision of libraries, baths, and open spaces. It is disappointing that emotion still governs methods of relief, that the rich give to relieve their own feelings rather than to relieve the poor, that the busy and kindly start new charities rather than work with others; that the absenteeism of those who might be channels of civilising influences is still the rule; that it remains true to say that the poor die before their time, suffer unduly for want of air, space, and water, and have not the happiness which comes from calm and knowledge. It is disappointing that so little has been done to advance higher education.

It is most disappointing that during all the years there has been no attempt to fit the Church for its work, no reform in the most unreformed of national institutions: that the purse or the patron still appoint to the cure of souls, that the incumbent remains an autocrat, and that its vast income is so administered that one man is rich on his thousands a year, while another starves on fifty pounds a year.

There is much in a retrospect of twenty years to rouse satisfaction, and much to rouse disappointment. On the whole it may be said that the standard of comfort in the East End has risen. The people are better housed, better fed, and better clad ; they take more pleasure, and take it in more wholesome ways ; there is less rowdyism in the streets, and there is now some interest in public affairs. But while this statement is true if it be taken generally, it must at the same time be remembered that there are thousands of families who live on the brink of starvation with low and uncertain wages, that there are many dwellings still unfit for occupation, that there is a large degraded class, and that the causes which make for poverty are still operating. On the whole, too, it may be said that the level of life has not risen ; there is no greater pleasure in the play of the imagination, no higher reach for hopes, no greater admiration for whatsoever things are beautiful, good, or virtuous. The people pursue what is comfortable, and value the good they can measure with eye, touch, or taste. But again, while this is true as a general statement, it must be remembered that there are some who have found in reading and study a new means of life, men and women who deny themselves comforts to buy a book, and find more pleasure in a flower or a story than in a big dinner. These exist to show that without more wages or more leisure people might live their lives on a higher plane.

Lastly, on the whole, it may be said that there has been a decrease of old-fashioned honesty, an increase of impertinence and of the habit of gambling. Under the influence of teaching, some good and some bad, stealing and lying no longer rank among the chief vices. Men and women who would not commit a vulgar theft or pick a pocket, think it little evil to cheat the railway or tramcar company, to claim as property chance findings, or to "best" a tradesman or employer. There is much talk about what is right in little matters, but the "robust conscience" which damns as wrong any departure from simple honesty and truth is often wanting. Mothers are no longer so stern about truth speaking in their children, they often pass over this as of little consequence, and in the schools the accepted assumption is that an excuse is an untruth. A workman's word can hardly be counted as his bond, and a promise even to join a party is not one on which to place dependence.