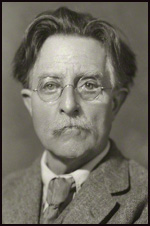

Raymond Unwin

Raymond Unwin, the younger son of William Unwin and his wife, Elizabeth Sully Unwin, was born in Whiston, near Rotherham on 2nd November 1863. William Unwin had inherited a tannery but at the age of fifty decided to become a student at Balliol College. After graduating he began associating with progressive figures such as Arnold Toynbee and Samuel Barnett.

Raymond attended Magdalen College School, and with his father's encouragement, hear John Ruskin and William Morris lecture in Oxford. During this period he became friends with Edward Carpenter. According to his biographer, Andrew Saint: "Unwin contemplated entering the Church of England, as his elder brother William did. But he was diverted (to his father's disappointment) into a life of social activism, reputedly on the advice of Samuel Barnett, who bade him ask himself which concerned him more, humanity's sinfulness or its unhappiness. Another influence may have been his friendship with the charismatic radical and homosexual Edward Carpenter, who had left the church and after some years as a university extension lecturer settled in the Sheffield and Chesterfield area from 1878. After declining a scholarship offered at Magdalen College, Unwin in 1881 took up an engineering apprenticeship with an affiliate of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company at Chesterfield."

Unwin became very involved in politics and joined the Socialist League, an organisation founded by William Morris. Other members included Walter Crane, Eleanor Marx, Ernest Belfort Bax and Edward Aveling. He contributed to the the league's magazine, Commonweal, and became friends with other radicals such as John Bruce Glasier and Ford Madox Ford. During this period Unwin fell in love with his cousin, Ethel Parker. However, because of his socialist beliefs, her parents refused to allow them to become engaged. He therefore went to live with Carpenter in his community founded at Millthorpe. Carpenter described him as "a young man of cultured antecedents… healthy, democratic, vegetarian".

In 1885 Unwin found work as an engineering draughtsman in Manchester. He gradually lost his revolutionary views and eventually became a Christian Socialist and was active in the Labour Church. In 1887 Unwin returned to the Staveley Coal and Iron Company as chief draughtsman, at first designing mining equipment, but then concentrating on the company's colliery housing. Unwin married Ethel Parker in a civil ceremony in 1893.

In 1894 Unwin's joined forces with Barry Parker to design a church for the mining community of Barrow Hill. According to Andrew Saint: "Unwin devised the strategy and layout and Parker the aesthetic detail; and such, as a rule, was to be the division of labour in their later working relationship. There followed the formal architectural partnership of Parker and Unwin, run between the brothers-in-law on an easy and amicable basis... Housing was always the focus: initially the internal planning of the middle-class home or artisan's house, then the grouping of small houses, and finally complete suburban and civic layouts, as Unwin's mastery of all sides of ‘the housing question’ grew. The partners' early practice consisted largely of arts and crafts homes for progressive businessmen, furnished with ample living-rooms and inglenooks... such designs alternate with picturesque, communal groups of working-class cottages round an open green, with plans offering bigger living-rooms at the expense of the outmoded front parlour."

On 10th June 1899, Ebenezer Howard and his friends established the Garden City Association. The Association organised lectures on "garden cities as a solution of the housing problem" which were addressed "to educational, social, political, co-operative, municipal, religious and temperance societies and institutions". Members included Unwin, Edward Grey, William Lever, Edward Cadbury, Ralph Neville, Barry Parker, Thomas Howell Idris and Aneurin Williams.

In 1900 the Garden City Limited was established with share capital of £50,000. The following year a conference was held at Bournville which three hundred delegates attended. Unwin gave a talk at the conference and this led to Joseph Rowntree commissioning him and his partner, Barry Parker, to design houses for his workers in New Earswick. As John Moss-Eccardt pointed out: "Both young men wanted to express their convictions, which were greatly influenced by Ruskin and Morris, in visual architecture... This was an important part of the social reform movement, more than a mere alleviation of poor housing and environmental conditions in industrial towns. It ranked as a forerunner of garden cities in that it paid attention deliberately to creating an environment which promoted health and happiness in its inhabitants."

In 1903 the Garden City Association had over 2,500 members. The Garden City Pioneer Company was constituted, with Ebenezer Howard as managing director, to find a suitable site for the first garden city. In 1903 Howard purchased 3,818 acres in Letchworth for £155,587. Howard employed Unwin and Barry Parker as the architects responsible for building Letchworth Garden City.

Unwin explained: "The successful setting out of such a work as a new city will only be accomplished by the frank acceptance of the natural conditions of the site; and, humbly bowing to these, by the fearless following out of some definite and orderly design based on them ... such natural features should be taken as the keynote of the composition; but beyond this there must be no meandering in a false imitation of so-called natural lines." Parker also held strong views on creating a beautiful environment. He believed that the destruction of a single tree should be avoided, unless absolutely necessary. It was decided that it was important to make full "use of the undulating nature of the terrain to provide vistas and prospects. By grouping numbers of houses together it was possible to have large gaps between the groups, thus providing views of gardens, countryside or buildings beyond."

Andrew Saint has argued: "The concept of the self-sufficient garden city promoted by Howard in Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1898–1902) having been entirely diagrammatic, Unwin was in effect asked to endow Letchworth with an image and identity. This raised issues of industrial and civic planning, phasing, and investment on a scale that no British architect had hitherto faced. The plan was revised in 1905–6, when work at Letchworth commenced. The housing areas got the earliest attention, Unwin tackling road layout, grouping, plot size, style, and supervision with originality and a remarkable perception of the complex issues. But Letchworth's civic centre, which was allotted an axial approach perhaps derived from Wren's plan for rebuilding London, grew too slowly for the ideas of Parker and Unwin to be carried through, and remains a grave disappointment. Despite Unwin's critical role at Letchworth, where he lived between 1904 and 1906, he never identified wholly with Howard's obsession with autonomous garden cities on virgin sites detached from metropolitan influence, and indeed left further work at Letchworth to Parker after 1914."

Unwin was also involved in the building of the Hampstead Garden Suburb. The main sponsor was Henrietta Barnett, wife of Unwin's early mentor Samuel Barnett. Parker and Unwin designed "short rows of houses with deep gardens, culs-de-sac, open courts, advanced and recessed frontage lines, boundary hedges, a varied geometry of open spaces, ‘vista-stoppers’ for sight-lines, and skewed road junctions". In 1906 to Raymond and Ethel Unwin, moved to Wyldes, a farmhouse on the southern edge of Hampstead.

In 1909 Unwin published Town Planning in Practice (1909). In 1914 Unwin dissolved his partnership with Barry Parker and started work as chief town planning inspector to the Local Government Board. During the First World War he was seconded as chief housing architect to the wartime Ministry of Munitions. This marked the start of Unwin's alliance with Christopher Addison, who at that time was minister of munitions. In July 1917 Unwin joined Addison when he became minister of reconstruction.

Unwin was also appointed to the Local Government Board's Tudor Walters Committee. Its task was to report on providing working-class dwellings across the country after the war. In the words of Prime Minister David Lloyd George, "homes fit for heroes". Andrew Saint argued: "By now it was clear to Unwin that adequate housing for the nation could not be secured without a concerted municipal programme, based on the direct subvention from central government that had been signally missing at Letchworth and in the garden suburbs. His was the dominant hand in the bold, progressivist tone of the Tudor Walters report, published in October 1918, which called for obligatory state provision of housing via local authorities. In June 1919 the Ministry of Health took over housing responsibilities from the Local Government Board, with Addison as its head. Addison immediately pushed through the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919, which endorsed the Tudor Walters recommendations and ushered in universal local-authority housing. It was accompanied by a Housing Manual largely drafted by Unwin, now chief housing architect to the Ministry of Health, with layouts and house plans following simplified models of the Parker and Unwin idiom."

The 1919 Housing Act included a government subsidy to cover the difference between the capital costs and the income earned through rents from working-class tenants. As Kenneth O. Morgan has argued: "Controversy dogged the housing programme from the start. Progress in house building was slow, the private enterprise building industry was fragmented, the building unions were reluctant to admit unskilled workers, the local authorities could hardly cope with their massive new responsibilities, and Treasury policy overall was unhelpful. In addition, the costs of the Treasury subsidy began to soar, with uncontrolled prices of raw materials leading to apparently open-ended subventions from the state... However, Addison could ultimately claim that, in spite of all difficulties, 210,000 high-quality houses were built for working people, and that an important new social principle of housing as a social service had been enacted."

Unwin was disappointed by this figure but his ideas also appeared in the 1924 Housing Act introduced by John Wheatley, the housing minister in the first Labour Government. The legislation involved developing a partnership between political parties, local authorities and specially appointed committees of building employees and employers. The plan was to build 190,000 new council houses at modest rents in 1925, and that this figure would gradually increase until it reached 450,000.

In 1931 Unwin became president of the Royal Institute of British Architects. The following year he was knighted in 1932. His daughter, Peggy married Curtice Hitchcock, a close friend of Woodrow Wilson. Unwin gave advice to President Franklin D. Roosevelt about his New Deal housing programmes. In 1936 accepted a visiting professorship for four months of the year at Columbia University. His friend, Lewis Mumford described him as "politically gifted, dispassionate, reasoned, always a bit of a Quaker, a sound practical man due to his apprenticeship as an engineer".

Raymond Unwin died at Old Lyme, Connecticut, on 28th June 1940. His biographer, Andrew Saint, has argued: "It may be claimed that Raymond Unwin had a greater beneficial effect on more people's lives than any other British architect. Creative ideas for improving cottage plans and housing layout had been developed, notably in the factory villages of Bournville and Port Sunlight, before he adopted them. But he fought for them and refined them at every technical and political level, and succeeded in carrying through a national and to some extent international revolution in housing standards. Adamant in his zeal for the benefits of low-density planning as against either undisciplined sprawl or multi-storey flats in cities (which he consistently opposed), he won his case through quiet powers of persuasion united with technical concentration."

Primary Sources

(1) John Moss-Eccardt, Ebenezer Howard (1973)

It has often been said that Howard invented garden cities and attention has been drawn to the similarity between the methods of the inventor of mechanical devices and the way in which the garden city idea came about. There can be no disagreement concerning the pre-eminently practical approach which he adopted towards the problems which interested him. Coupled with this was an apparent lack of self-interest which enabled him to see his objectives clearly and uncluttered by the impaired judgement that self-seeking produces.

Living in an age where social stratigraphy was more rigid than in our own, he seems to have been untroubled by social pretensions or aspirations, being more concerned with the lot of the less fortunate than for himself. This attitude must surely have stemmed from his religious convictions which were strong but not sectarian, his liberal political views, and an idealism strongly tinged with a pinch of scepticism.... Finally, we might add the lack of a sophisticated higher education to the advantages enjoyed by this observer of the chaos and squalor of late nineteenth-century industrial England. In contrast, many of his contemporaries had allowed their minds to become filled to bursting with the copious outpourings of the reformers of this and previous centuries.

Through his church connections and his professional contacts Howard became conversant with leading questions of the day and their protagonists. Subjects ranged over religion and science, politics, poverty and riches, economics, urban congestion, and the decline of the countryside. He became involved in discussions on these topics but was especially interested in questions of social significance. He went to the heart of the matter when he wrote in his book: "Religious and political questions too often divide us into hostile camps- and so in the very realms where calm, dispassionate thought and pure emotions are the essentials of all advance towards right beliefs and sound principles of action, the din of battle and the struggles of contending hosts are more forcibly suggested to the onlooker than the really sincere love of truth and love of country which, one may yet be sure, animate nearly all breasts."

By temperament Ebenezer Howard was as capable of championing a cause as those with whom he debated but he was able to stand a little apart and assess the value of what he had learnt, just as the inventor must prove his various modifications before adapting them. Thus, little by little, a recipe was concocted from the various ideas which he heard and tested against his common sense. One may imagine him like a small boat steering his way through the shoals of opinions always holding to his course until he reaches harbour.