Jacob Epstein

Jacob Epstein, the second son and third of eight surviving children of Max Epstein (1859-1941) and his wife, Mary Solomon (1859-1913) was born on 10th November 1880 at 102 Hester Street, New York City. Both parents were from Jewish families and had immigrated to the United States from Augustów, Poland. On arrival his father changed his name to Epstein.

Epstein was educated at free local school. This ended when he was thirteen, but he attended classes and events organized by the settlement house movement at the nearby Neighbourhood Guild and Education Alliance. In 1893 he began attended classes at the Art Students' League. It had no entrance requirements and no set course. With teachers such as Thomas Eakins, Robert Henri, John Sloan, Art Young, George Luks, Boardman Robinson, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Howard Pyle, George Grosz and George Bellows, it developed a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. According to his biographer, Evelyn Silber: "Increasingly he rejected the rigorous Orthodox observance of his upbringing. His early drawings were inspired by the lively multi-ethnic communities round him in the Lower East Side, especially the Jewish community. He organized a local artists' exhibition at the Hebrew Institute during 1898 and was emerging as the leading figure in a nascent group of Jewish New York artists."

The journalist Hutchins Hapgood commissioned him to carry out most of the illustrations for his pioneering book about the Lower East Side, The Spirit of the Ghetto: Studies of the Jewish Quarter in New York (1902). Soon after this he began attending an Art Students' League class for sculptors' assistants run by George Grey Barnard.

In September 1902 Epstein moved to Paris. Epstein attended the École des Beaux-Arts between October 1902 and March 1903 and the Académie Julian from April 1903 to 1904. The following year he decided to settle in London. In November 1906 he married Margaret Dunlop (1873–1947). They lived at 219 Stanhope Street, Regent's Park.

Epstein became involved with the New English Art Club. It had been stablished by Henry Tonks, Frederick Brown and Philip Wilson Steer in reaction to the conservative attitudes of the Royal Academy. He also made friends with George Bernard Shaw, who used his influence to promote Epstein's skills as a penetrating observer and brilliant modeller.

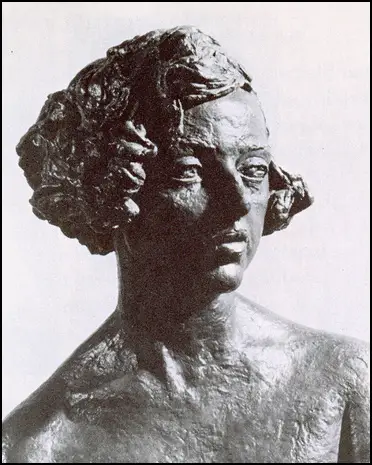

Epstein was commissioned by Charles Holden to carve eighteen figures representing the ages of man and woman on the British Medical Association building in the Strand. On 19th June, 1908, the Evening Standard complained about the frank depictions of nudity. Other important works produced during this period included Romilly John (1907), Euphemia Lamb (1908)and Lady Gregory (1910).

In 1909 Jacob Epstein was also asked to produce a tomb for the grave of Oscar Wilde. The English press praised Epstein’s creation, which consisted of a huge block of stone, carved on one face with a flying figure, half demon, half angel. Instead, it was the French who raised a furore, covering the tomb with tarpaulin, and even placing it under police guard. The problem was the figure’s exposed genitalia, which the Parisian authorities wanted Epstein to conceal. He refused, and the sculpture at Père Lachaise Cemetery remained under wraps until the outbreak of the Second World War, when the tarpaulin was removed.

In 1914 Epstein became associated with a new movement called Vorticism. The leader of this group was Percy Wyndham Lewis. In his journal, Blast, Lewis attacked the sentimentality of 19th century art and emphasized the value of violence, energy and the machine. In the visual arts Vorticism was expressed in abstract compositions of bold lines, sharp angles and planes. Others associated with this movement included Christopher Nevinson, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, William Roberts, David Bomberg and Edward Wadsworth. It has been argued that his most experimental work, Rock Drill (1914) reflects "the embodiment of the vorticist passion for dynamism and of their virile aesthetic."

Epstein's friends campaigned for him to become a government war artist during the First World War. This idea was rejected by the authorities and in 1917 he was conscripted and became a private in the Jewish 38th battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. He was discharged in 1918 without leaving England, having suffered a mental breakdown.

The Risen Christ, produced as a result of his experiences in the war caused problems when it was exhibited in 1920. Epstein considered the figure to be an anti-war statement and declared that he would ideally like it to be remodelled and made hundreds of feet high as a "mighty symbolic warning to all lands." John Galsworthy remarked after visiting the exhibition that: "I can never forgive Mr. Epstein for his representation of Our Lord."

Epstein became part of the artistic set that gathered at the Café Royal. This included Percy Wyndham Lewis, D. H. Lawrence, Maurice Baring, Jacob Epstein, Augustus John, Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry, Aleister Crowley and Nina Hamnett.

In 1919 Clare Sheridan modelled for Epstein. She later recalled in her autobiography, Naked Truth (1927): "Epstein at work was a being transformed. Not only his method was interesting and valuable to watch, but the man himself, his movement, his stooping and bending, his leaping back posed and then rushing forward, his trick of pressing clay from one hand to the other over the top of his head while he scrutinised his work from all angles, was the equivalent of a dance... He wore a butcher-blue tunic and his black curly hair stood on end; he was beautiful when he worked. Then I learnt the thing which has counted supremely for me ever since... He did not model with his fingers, he built up planes slowly by means of small pieces of clay applied with a flat, pliant wooden tool. He told me that he could not understand how other sculptors could work with their fingers which with him merely left shiny fingerprints on the surfaces. This was what I had always suffered from, the shiny smooth result of my finger touch. It had exasperated and perplexed me. It is his method of building up that gives Epstein's surfaces their vibrating and pulsating quality of flesh. Without his ever suspecting it, I acquired from merely watching him, knowledge that revolutionised mywork."

In August 1921 Kathleen Garman and Mary Garman were having dinner at the Harlequin when they became aware of Epstein who kept staring at them from the other side of the room. Cressida Connolly, the author of The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans (2004), claims: "He was unkempt, with wild hair, but the intensity with which he regarded her, the concentration in his blue eyes, made her (Kathleen) unable to look away. Then a waiter brought over a note: would the women join the stranger's table? Kathleen was amused by the interest, but she and Mary left without accepting the invitation."

A few days later Kathleen was again back in the Harlequin. This time she was alone and she agreed to sit with the man. Jacob Epstein told her he was a sculptor and asked her to sit for him. Kathleen not only become Epstein's model but his mistress. As Cressida Connolly has pointed out: "Mrs Epstein had always been tolerant of her husband's affairs, encouraging his models and mistresses to come and live with them, preferring to keep her enemies close... But Kathleen, nearly thirty years her junior, was different. She was never just another of Epstein's infatuations, whom Mrs Epstein could brush off after he'd finished sculpting them. She wasn't biddable. More than a lover, she was a parallel wife. From the beginning, Mrs Epstein disliked her intensely, rightly intuiting that she was to be her greatest rival."

Kathleen's father, Walter Garman suffered a heart-attack at Oakeswell Hall in May 1923. Kathleen was at his side when he died a few days later. The family believed that he had been killed by overwork, for he was only sixty-two. Garman also strongly disapproved of Kathleen's relationship with Jacob Epstein and she was left no money in his will.

In the summer of 1923 Margaret Epstein invited Kathleen to her home in Guildford Street when her husband was away. According to Cressida Connolly: "Mrs Epstein took Kathleen into a room and locked the door before producing a pearl-handled pistol from under her capacious skirts... and shot her. The bullet hit Kathleen just to the right of her left shoulder blade, whereupon Mrs Epstein panicked and ran out of the room, leaving the bloodied Kathleen to stagger out into the street alone." Epstein visited Kathleen in hospital and paid her medical bills. Her shoulder was badly scarred and she was never afterwards able to wear sleeve-less dresses. She agreed not to bring charges against his wife as Epstein feared any scandal would damage his reputation.

In 1924 Kathleen gave birth to Theodore (Theo). Over the next five years she had two more children fathered by Epstein: Kathleen (b. 1926) and Esther (b. 1929). Throughout the 1920s Epstein came to stay with Kathleen two or three times a week. Even so, according to a letter he wrote at the time to Kathleen: "How I wish we were together you and I in our little place. How happy I would be beyond words and all expression in words."

Epstein was a pacifist and he joined with other left-wing artists and writers, including David Low, Henry Moore and Eric Gill to form a National Congress organised by the British section of the International Peace Campaign. He was also involved in the Artists' International Association's efforts on behalf of the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. He was furious when the Foreign Office refused Epstein a visa when he wanted to visit Spain in 1937.

In March 1947, Jacob's wife, Margaret fell on the steps of her house and fractured her skull. She was rushed to hospital where she died from a brain haemorrhage. Kathleen rejected Jacob's suggestion that she went to live with him in Hyde Park Gate. Their son, Theo, was also an artist but he died of a heart-attack in January 1954. Their daughter, Esther, committed suicide nine months later.

Evelyn Silber has argued that in the early 1950s "Epstein finally began to receive the public recognition he craved; his last major carving, Lazarus was exhibited at Battersea Park as part of the Festival of Britain (1951) and was purchased for the chapel of New College, Oxford, and Madonna and Child (1950–52) for the convent of the Holy Child Jesus, Cavendish Square, London, received unprecedented critical and public acclaim. He had ceased to be an enfant terrible and had become a grand old man trusted to handle religious and symbolic themes with dignity and conviction. Ignoring his failing health and pushing aside grief at the tragic deaths of two of his children, he completed eight large public commissions during his last decade, as well as many commissioned portraits."

Epstein, who was knighted in 1954, married Kathleen Garman on 27th June, 1955. His final work included a sculpture of Jan Christiaan Smuts for Parliament Square (1955); Christ in Majesty at Llandaff Cathedral (1955) and the Trades Union Congress War Memorial (1957) in Great Russell Street and St Michael and the Devil for the new Coventry Cathedral (1958).

Jacob Epstein died of a heart-attack on 19th August 1959. Kathleen's friend, Rosie Price, argued that Kathleen Garman had made a terrible sacrifice: "She devoted her life... to that man and his work. All Epstein wanted to do was work. Her life was almost a sacrifice to him, to his art."

Primary Sources

(1) Clare Sheridan, Naked Truth (1927)

Those days are unforgettable. Epstein at work was a being transformed. Not only his method was interesting and valuable to watch, but the man himself, his movement, his stooping and bending, his leaping back posed and then rushing forward, his trick of pressing clay from one hand to the other over the top of his head while he scrutinised his work from all angles, was the equivalent of a dance...

He wore a butcher-blue tunic and his black curly hair stood on end; he was beautiful when he worked. Then I learnt the thing which has counted supremely for me ever since... He did not model with his fingers, he built up planes slowly by means of small pieces of clay applied with a flat, pliant wooden tool. He told me that he could not understand how other sculptors could work with their fingers which with him merely left shiny fingerprints on the surfaces. This was what I had always suffered from, the shiny smooth result of my finger touch. It had exasperated and perplexed me. It is his method of building up that gives Epstein's surfaces their vibrating and pulsating quality of flesh. Without his ever suspecting it, I acquired from merely watching him, knowledge that revolutionised my work.

(2) Peggy Guggenheim, Out of the Century (1979)

Garman was the son of a family doctor who had had a large practice outside Birmingham. There he had lived in a big house with a garden, completely removed from the world, with his one brother and seven sisters. His father died while Garman was still at Cambridge, and Garman felt his loss very much and his early responsibilities of being head of the family. His mother was a gentle English lady living in retirement and great modesty. She was supposed to be the illegitimate daughter of Earl Grey, and indeed she looked aristocratic. She was so feminine and so ladylike she had always done exactly what her husband had wanted, and now, although she rarely saw Garman, she adored him and treated him in the same way. He had just bought a little house for her in Sussex near the downs and he intended to go down there for weekends...

Garman drove me to Sussex to show me the house he had bought for his mother. It was in a little English village called South Harting, just under the downs. The village was absolutely dead, like all such places in England, but it was in the midst of the most lovely country. Naturally, it had a fine pub. Garman also took me to see his sister Lorna and his brother-in-law, the publisher Ernest Wishart, whom he called Wish. They had a lovely home. Garman and Wish seemed to be the very best of friends, having been to Cambridge together. Wish's wife Lorna was the most beautiful creature I had ever seen. She had enormous blue eyes, long lashes and auburn hair. She was very young, still in her early twenties, having been married at the age of sixteen. Out of seven sisters, she was Garman's favorite. They were all extraordinary girls. One of them was married to a fisherman in Martigues, and another one had three children by a world-famous sculptor. Another lived in Herefordshire with her illegitimate child, while a fourth spent half the year as a maidservant in order to be able to live in peace the other six months in a cottage she had bought on Thomas Hardy's favorite heath. Later she adopted a little boy and was reported to have had a love affair with Lawrence of Arabia, whom she met on the heath, but when I knew her she was most virginal. Another one was married to the famous South African poet Roy Campbell. They were Catholic and later became Fascist and lived in Spain. One very normal one married a garage owner and led a happy life with two children. In his youth Garman must have been overwhelmed by so many women, and preferred not to see most of them any more. However, I was fascinated by them and eventually managed to meet them all. Garman had a younger brother whom he liked. He had returned from Brazil and was now farming in Hampshire.