Mary Garman

Mary Garman, the daughter of Walter Garman, the medical officer for Wednesbury, was born in 1898. Her mother, Margaret Magill, who was nearly twenty years younger than her husband, had eight other children: Sylvia (1899), Kathleen (1901), Douglas (1903), Rosalind (1904), Helen (1906), Mavin (1907), Ruth (1909) and Lorna (1911). The family lived at Oakeswell Hall, Wednesbury.

Mary went to art classes in Birmingham with her sister Kathleen. They also bought books and when Walter Garman caught them reading Madame Bovary, he summoned all the children and burned it on the fire in front of them.

In 1919 the two sisters rebelled and ran away to London. Kathleen took a job helping with the horses that pulled carriages for Harrods and also worked as an artist model, whereas Mary drove a delivery van for Lyons' Corner Houses. Dr. Garman was deeply shocked by this behaviour and eventually decided to give both his daughters an allowance, which enabled them to give up their jobs and enroll at a private art school called the Heatherley. This money also helped them to rent a house in Regent Square.

Kathleen and Mary found themselves as part of the artistic set that gathered at the Café Royal. This included Percy Wyndham Lewis, D. H. Lawrence, Maurice Baring, Jacob Epstein, Augustus John, Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry, Aleister Crowley and Nina Hamnett.

In August 1921 Kathleen and Mary were having dinner at the Harlequin when they became aware of a strange man who kept staring at them from the other side of the room. Cressida Connolly, the author of The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans (2004), claims: "He was unkempt, with wild hair, but the intensity with which he regarded her, the concentration in his blue eyes, made her (Kathleen) unable to look away. Then a waiter brought over a note: would the women join the stranger's table? Kathleen was amused by the interest, but she and Mary left without accepting the invitation."

A few days later Kathleen Garman was again back in the Harlequin. This time she was alone and she agreed to sit with the man. Jacob Epstein told her he was a sculptor and asked her to model for him. Kathleen not only become Epstein's model but his mistress.

Two months later Mary and Kathleen agreed to allow a friend, Stuart Gray, to live in the cellar of the house they were renting in London. One of his friends who came to visit him was the poet Roy Campbell. He later recalled: "When I saw her (Mary) I experienced, for one of the few times in my life, the electric thrill of falling in love at first sight."

Cressida Connolly has pointed out: "Within three days he had moved into the girls' studio room. Tall and thin, with startlingly blue eyes, he was already writing poetry, living on beer and forgetting to eat - or eating only radishes, their leaves and all, bought from a market stall. The girls decided to fatten him up, and the three of them would lie, arm in arm, in front of the fire while he read them fragments from the poems which would become his first book."

In December 1921 Roy Campbell was taken to Oakeswell Hall to meet their father, Walter Garman. Kathleen introduced him: "Father, this is Roy, who's going to marry Mary." Garman was furious as he did not approve of his future son-in-law. Not only was he unemployed, it was also clear that he had a serious drink problem.

Kathleen and Mary took Campbell to the Café Royal and introduced him to their friends such as Percy Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein and Augustus John. Campbell recorded in his autobiography, Broken Record (1934): "No other contemporary woman ever had so much poetry, good, bad and indifferent, written about them, or had so many portraits and busts made of them."

Mary and Roy Campbell were married in 1922. The bride wore a long black dress with a golden veil whereas he put on his old suit. One guest observed that when he knelt at the altar he had holes in the soles of his shoes, padded with newspaper. Percy Wyndham Lewis was one of the guests at the wedding: "The marriage feast was a distinguished gathering, if you are prepared to admit distinction to the Bohemian, for it was almost gipsy in its freedom from the conventional restraints."

The marriage resulted in Mary and Kathleen Garman drifting apart. The main reason for this was Campbell's right-wing political views. This resulted in a growing conflict between him and Jacob Epstein. Campbell had strong anti-Semitic views and in his autobiography wrote that the Jewish race was "intellectually subversive... that has none of our visual sense, but a wonderful dim-sighted instinct for dissolving, softening, undermining, and vulgarising."

After their carriage the couple moved to Aberdaron in Wales. Later Roy Campbell recalled: "Though we were very happy, my wife and I had some quarrels since my ideas of marriage are old-fashioned about wifely obedience and in many ways she regarded me as a mere child because of being hardly out of my teens. But any marriage in which a woman wears the pants is an unseemly farce. To shake up her illusions I hung her out of the fourth-floor window of our room so that she should get some respect for me... My wife was very proud of me after I had hung her out of the window and boasted of it to her girl friends."

Romilly John, the son of Augustus John, went to visit them in their converted stable called Ty Corn: "I shall never forget the day we moved in or the dismay with which I first contemplated the hovel we were about to inhabit. The floor was earth stamped unevenly down, and in some places the mud had fallen from between the rocks of which the walls were built, so that the wind came whistling in. Mary and I both fell a prey to unspeakable gloom - I believe Mary even shed some natural tears. But it was astonishing how quickly we cheered up under the influence of Roy's indomitable spirit. I really think it had never crossed his mind that the cottage in any way fell short of a desirable country residence; nor did it, when the holes had been stuffed up and a great fire was roaring up the chimney."

In the spring of 1924, after the birth of Tess, the couple moved back to London. They found a flat in Fitzroy Street and socialised with Nina Hamnett, Kathleen Hale, Augustus John, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Jacob Kramer and Bernard Meninsky.

In May 1924 The Flaming Terrapin was published simultaneously in Britain and the United States. Although it received very good reviews, it sold poorly and the couple continued to live in poverty. The financial situation was not helped by Campbell's heavy drinking. Later that month he sailed for Durban to see his parents. He told his mother before the trip: "I will hate leaving my two girls (Mary and Tess), but I think that a trip home will set me up again."

Roy Campbell was soon missing Mary and he wrote a letter urging her to join him in South Africa. "All the lovely things I see are only half as lovely as they would be if you were here to share them. You have taught me to look at things in the same way as you do and I do miss half their beauty when you're not there." Mary and Tess reached Durban in December 1924.

Campbell continued to write poetry. He told a friend: "I should never be half the writer I am, I'm afraid, if it weren't for her. She positively keeps me alive. She is the perfect model of what an artist's wife should be. But I get all the damned credit for it." While in South Africa the Campbells became friends with William Plomer and Laurens van der Post. They helped Campbell start a new literary, political and cultural review, Voorslag. It was financed by Lewis Reynolds. Mary also helped with the production of the magazine until the birth of Anna in May 1926. Soon afterwards, Campbell resigned over a disagreement with Reynolds, who disliked the magazine's promotion of a more racially integrated South Africa.

In December 1926 the Campbells decided to return to England. Mary wrote to William Plomer during her stay with her mother in Herefordshire: "We spent a fortnight in London and met almost everyone we ever knew there, but I got ill and had to come back here... London itself is the most delightful place on earth. I cannot describe the childish feeling of pleasure I always have on going back there."

Mary's brother, Douglas Garman, and two of his friends, Ernest Wishart and Edgell Rickword, had established a quarterly literary review, Calendar of Modern Letters. Campbell provided poems and reviews for the journal. He also received £20 a month from his father's estate, who had recently died in South Africa.

The Campbells moved to Sissinghurst in Kent and in May 1927 they met Vita Sackville-West in the village post office. She invited them to dinner with her husband, Harold Nicolson. Other guests included Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf and Richard Aldington. Mary wrote to William Plomer about the dinner party: "Vita Nicolson appeared, and in her wake, Virginia Woolf, Richard Aldington and Leonard Woolf. They looked to me rather like intellectual wolves in sheep's clothing. Virginia's hand felt like the claw of a hawk. She has black eyes, light hair and a very pale face. He is weary and slightly distinguished. They are not very human."

In September 1927 Mary and Vita began an affair. Mary wrote: "You are sometimes like a mother to me. No one can imagine the tenderness of a lover suddenly descending to being maternal. It is a lovely moment when the mother's voice and hands turn into the lover's."

Later that month, Vita Sackville-West offered the Campbells the opportunity to live in a cottage in the grounds of Sissinghurst Castle. They accepted but later Roy Campbell objected when he discovered that his wife was having an affair with Vita: "It was then that we entered the most comically sordid and silly period of our lives. We were very stupid to relinquish our precarious independence in the tiny cottage for the professed hospitality of one of the Stately Homes of England, which proved to be something between a psychiatry clinic and a posh brothel."

When Campbell was in London he told C.S. Lewis of the affair he replied: "Fancy being cuckolded by a woman!" According to Cressida Connolly: "Roy was a proud man, and this remark so punctured his pride that he returned to Kent in a towering rage. A terrified Mary took refuge at Long Barn, where Dorothy Wellesley sat up all night with a shotgun across her knees."

Campbell had a meeting with Vita Sackville-West about the affair. Afterwards he wrote: "I am tired of trying to hate you and I realize that there is no way in which I could harm you (as I would have liked to) without equally harming us all. I do not dislike any of your personal characteristics and I liked you very much before I knew anything. All this acrimony on my part is due rather to our respective positions in this tangle."

It was agreed that the affair would come to an end. However, Mary found the situation very difficult and wrote to Vita: "Is the night never coming again when I can spend hours in your arms, when I can realise your big sort of protectiveness all round me, and be quite naked except for a covering of your rose leaf kisses?" When Roy Campbell went into hospital to have his appendix out, the relationship resumed.

Virginia Woolf was also very jealous of the affair. She wrote to Vita: "I rang you up just now to find you were gone nutting in the woods with Mary Campbell... but not me - damn you." It is believed that Woolf's novel Orlando was influenced by the affair. In October 1927 Virginia wrote to Vita: "Suppose Orlando turns out to be about Vita; and its all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind (heart you have none, who go gallivanting down the lanes with Campbell) - suppose there's the kind of shimmer of reality which sometimes attaches to my people... Shall you mind?"

Vita Sackville-West replied that she thrilled and terrified "at the prospect of being projected into the shape of Orlando". She added: "What fun for you; what fun for me. You see, any vengeance that you want to take will be ready in your hand... You have my full permission." Orlando was published in October 1928, with three pictures of Vita among its eight photographic illustrations.

After reading the book, Mary wrote to Vita: "I hate the idea that you who are so hidden and secret and proud even with people you know best, should be suddenly presented so nakedly for anyone to read about... Vita darling you have been so much Orlando to me that how can I help absolutely understanding and loving the book... Through all the slight mockery which is always in the tone of Virginia's voice, and the analysis etc., Orlando is written by someone who loves you so obviously."

Vita also wrote several sonnets about Mary. These appeared in King's Daughter (1929). After the book was published she wrote to her husband, Harold Nicolson: "It has occurred to me that people will think them Lesbian... I should not like this, either for my own sake or yours."

Roy Campbell responded to the affair by writing the long satirical poem, The Georgiad. The poem caused a furore in the literary world as Campbell castigated the Bloomsbury Group. This included Vita who he described as the "frowsy poetess" in the poem:

Too gaunt and bony to attract a man

But proud in love to scavenge what she can,

Among her peers will set some cult in fashion

Where pedantry may masquerade as passion.

Campbell wrote to his friend Percy Wyndham Lewis: "Since The Georgiad (I hear) the Nicolson menage has become very Strindbergian. Each accusing the other for it and smashing the furniture about: but they are rotten to the core and I don't care about any personal harm I have done them - I take their internal disturbances as a justification of The Georgiad."

Mary and Roy Campbell decided to move to France in 1928 where they rented an old stone farmhouse, Tour de Vallier, near Martigues. The writer, Nancy Cunard, and her African-American lover, the pianist Henry Crowder, visited them in their new home. So did the poet, Hart Crane, the painter Tristram Hillier and the Irish writer Liam O'Flaherty, who Anna Campbell described as the "best-looking man she had ever seen, and one of the wildest."

In 1932, Jeanne Hewitt arrived in Martigues with her younger sister Lisa. Her marriage to Mary's brother Douglas Garman was in difficulty at the time. According to Cressida Connolly, the author of The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans (2004): "It seems that Mary and Jeanne became lovers at this time, and Mary's letters attest to a brief romance... It was during the same visit that Campbell began an affair with Jeanne's sister Lisa... who like her sister, was a considerable beauty."

With the publication of Adamastor (1930), Poems (1930) and The Georgiad (1931), the financial circumstances of the Campbells improved and they were able to move to a much larger farmhouse in the area. They now had the funds to hire a tutor, Uys Krige, to teach Anna and Tess. Anna later recalled: "I was jealous of the time he and Mary spent together... She painted him in the nude (a wonderful painting, rather like a Botticelli) so that I feel, even though I did not know, that they were having an affair. It must have been a light-hearted intimacy as there were no tears or scenes."

In 1933 they moved to Provence where Roy Campbell wrote the first volume of his autobiography, Broken Record (1934). The following year they went to live in Spain. After a spell in Barcelona they moved to Valencia. Finally they settled in Altea. It was at this time that they both decided to become Roman Catholics.

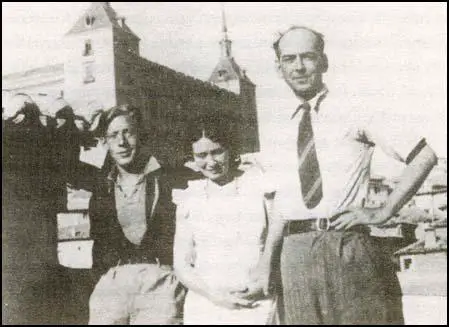

In June 1935 the Campbells moved to Toledo. Soon afterwards they met the 21-year-old poet, Laurie Lee. They invited him back to their house for dinner, where he ended up staying for a week. Lee moved on and eventually found work as a violinist and odd job man at the Hotel Mediterraneo in Almuñécar.

The Campbells continued to live in Toledo during the early stages of the Spanish Civil War. The Roman Catholic Church became a target of the Republicans and priests were attacked in the streets. Mary and Roy gave sanctuary to several monks. It became increasingly dangerous and after seventeen Carmelite Monks were killed in July, they decided to return to England.

They initially went to stay with Ernest Wishart and Lorna Wishart at Binsted. The Wisharts organised a dinner party that Christmas and the guests included Douglas Garman, Peggy Guggenheim and Edgell Rickword. A discussion on the Spanish Civil War caused a major rift in the family. Rickword later commented: "He (Campbell) was very good fun, by no means a fool. But where he got this crappy, hysterical sort of fascism from, I don't know." Campbell responded by describing Wishart's home as "Bolshevik Binsted".

Campbell also upset Kathleen Garman and Jacob Epstein with his support of Adolf Hitler. Epstein, was Jewish and had suffered from anti-Semitism. Campbell wrote: "One can forgive the Jews anything for the beauty of their women, which makes up for the ugliness of their men. But I fail to see how a man like Hitler makes any mistake in expelling a race that is intellectually subversive as far as we are concerned: that has none of our visual sense, but a wonderful dim-sighted instinct for dissolving, softening, undermining, and vulgarising."

Campbell wrote to his brother denying he was a fascist: "A considerable part of my attraction to the Right and aversion from the Left is due to the fact that there is more laughter and less grumbling among the soldierly people. I believe in family life and religion and tolerance: and I find far more tolerance to Britain in Italy than I find tolerance of Fascism in England." The Campbells moved to a cottage near Petersfield. Over the next few months he wrote what was considered to be a pro-fascist book Flowering Rifle (1939).

On the outbreak of the Second World War Campbell joined the King's African Rifles and in 1943 he was posted to Nairobi. He was discharged in 1944 on account of malaria contracted in Africa. They settled at 17 Campden Grove in Kensington and Campbell was employed by the BBC.

Roy Campbell continued to be a heavy drinker and he got involved in several fights because of his alleged fascist sympathizers. Campbell punched Stephen Spender in the face and exchanged blows with the poet Louis MacNeice.

Mary's daughter, Anna, argued that her mother sacrificed her own career in order to support her father's work: "She was very musical. She accompanied herself on the guitar... She painted divinely. These gifts were extraordinary... Mary was highly gifted. But you cannot be everything. In order to be the wife of a vulnerable poet of genius, she often neglected her gifts in order to have the stamina to cope with a life of great hardship. She had to be tough to live with my father."

Campbell spent time in South Africa before moved to Portugal in 1952 where he published his second volume of autobiography, Light on a Dark Horse (1951). When his Collected Poems was published Edith Sitwell wrote to him: "It is, I may say, one of the great things in my life, this lasting love between you and Mary, in an age of little, fireless unreal would-be emotions, gone in a moment, everything turned to ashes, to know that such greatness and undying love exists, unquenchable. You deserve, and she deserves, your poetry."

In April 1957 Roy and Mary drove to Spain. On the journey back, with Mary driving, a front tyre burst and their small car swerved into a tree. Roy Campbell died at the scene of the accident.

Mary purchased a home just outside Sintra in Portugal. According to Cressida Connolly, the author of The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans (2004): "The pink house on this hill of pines and cork trees was meant to be home to both the Campbells. As it was, Mary took up residence there alone. She was nearly sixty, but she looked much younger and was still beautiful."

According to her daughter, Anna, Mary lost her religious faith in 1977. "It seemed to disappear suddenly and without reason, like a bird alighting from a branch." Peter Alexander, the author of Roy Campbell: A Critical Biography (1982), interviewed her in her home in Portugal: "After dinner she would talk again, and in this mellow state would remember her love affairs... I got the impression that she regretted nothing. She had enjoyed her beauty to the full... She was a very warm and generous human being."

Mary Garman died after suffering a stroke on 27th February 1979. She was buried in the cemetery of São Pedro, near Sintra, with her husband Roy Campbell.

Primary Sources

(1) Mary Garman, letter to William Plomer (May 1927)

Our latest acquaintance is the daughter of Lord Sackville. She lived at Knole until she married Harold Nicolson. He has written a quite good book on Tennyson, and she has written a poem called The Land which has just won the Hawthornden Prize. They are both rather nice and live in Weald in a beautiful old house crammed with old tapestries, furniture etc. They have some lovely books, and we get quite a lot to read. I have just borrowed Lawrence's The Rainbow which is quite the best book he has written ... When I was talking to Harold ... suddenly Vita Nicolson appeared, and in her wake, Virginia Woolf, Richard Aldington and Leonard Woolf. They looked to me rather like intellectual wolves in sheep's clothing. Virginia's hand felt like the claw of a hawk. She has black eyes, light hair and a very pale face. He is weary and slightly distinguished. They are not very human.

(2) Cressida Connolly, The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans (2004)

After Mary's marriage, she and Kathleen were never as close as they had been when they shared the studio in Regent Square. The mutual disdain of Campbell and Epstein must have played its part in their estrangement, even though it never erupted into violence again. Some of Campbell's views would have been anathema to his future brother-in-law and to Kathleen. His much vaunted right-wingery was expressed with a brazenness which was more provocative than serious, but he succeeded in annoying many. Epstein had frequent occasion to defend himself against anti-Semitism, not least when the Christian images he made outraged their more reactionary spectators. Certain of his public sculptures were vandalized repeatedly, and at the end of the 1920s his house was daubed with swastikas and with scrawled messages like "Jew go home."