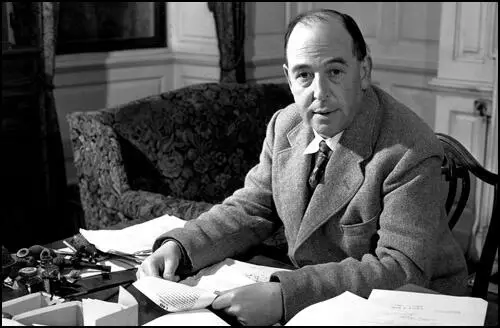

C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis, the son of Albert Lewis, a successful solicitor, was born in Belfast on 29th November 1898. He had a brother, Warren Lewis and the two boys were initially taught at home by his mother, Flora Lewis, and a governess.

Lewis later recalled that his family had a large library: "I took volume after volume from the shelves. I had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks in a field has of finding a new blade of grass".

In 1908 Lewis was sent away to join his brother at Wynyard School in Watford. Soon afterwards his mother died of cancer. He was very unhappy at the school and complained about the vicious and sadistic headmaster, Robert Capron. The school was eventually closed and Capron was committed to an insane asylum. Lewis moved to a preparatory school in Malvern.

Lewis attended Malvern College and in 1916 he won a scholarship to University College, Oxford. However, the Master of the College informed Lewis that, with the exception of one boy with health problems, everyone who had won a scholarship had joined the British Army in order to fight in the First World War. As the authors of Famous 1914-1918 (2008) pointed out: "As as Irishman, Lewis could legally have avoided service, there being no conscription in Ireland, but the thought never entered his head: he would serve."

Lewis initially joined a cadet battalion at Keble College. He made friends with a small group of students including Ernest Moore, Martin Somerville and Alexander Sutton. Lewis became a commissioned officer in the Somerset Light Infantry. He soon became very close to Laurence Johnson, who had also won a scholarship to Oxford University.

Lewis joined the regiment on the Western Front in November 1917. At the time the battalion was in a quiet sector of the front-line and was primarily engaged in pumping and clearing out waterlogged trenches. As Lewis later pointed out: "Through the winter, weariness and water were our chief enemies... One walked in the trenches in thigh gumboots with water above the knee, and one remembers the icy stream welling up inside the boot when you punctured it on concealed barbed wire." Tiredness was another major problem. Lewis admitted that "I have gone to sleep marching and woken again and found myself marching still."

In January 1918 Lewis was devastated when he heard that his great friend Alexander Sutton had been killed. Three months later Ernest Moore also lost his life. John Howe later recalled: "I saw him fall with a wound in his leg. I stopped and bound up the wound. While I was binding up his leg, he got another bullet right through the head, which killed him instantly." Moore was posthumously awarded the Military Cross.

In March the German Army launched the Spring Offensive. This included an attack at Arras where Lewis was based. After the Germans gained ground the Somerset Light Infantry was ordered to counter-attack at Riez du Vinage on 14th April 1918.

At 6pm, the heavy artillery opened fire on the German-held village. At 6.30pm a creeping barrage began. The plan was that the men would follow behind the exploding shells, at the rate of 50 metres per minute. Sergeant Arthur Cook later pointed out: "One of the most extraordinary advertisements of look out we're coming I have witnessed in this war, in full view of the enemy; how they must have chuckled with glee." According to Cook, the "barrage moved too quick, leaving the enemy free to open up a devastating machine-gun fire on the target they had been waiting for."

One of those hit by the machine-gun fire during the attack was Lewis' great friend, Lieutenant Laurence Johnson. He was taken to the nearest Casualty Clearing Station but he died the following morning. Martin Somerville was killed soon afterwards.

Lewis was one of those men who reached Riez du Vinage. "I took about 60 prisoners - that is, I discovered to my great relief that the crowd of field-grey figures who suddenly appeared from nowhere, all had their hands up."

The German artillery then began shelling Riez du Vinage. One of these shells exploded close to Lewis and he was peppered with shrapnel. "Just after I was hit, I found (or thought I found) that I was not breathing and concluded that this was death. I felt no fear and certainly no courage. It did not seem to be an occasion for either." When Lewis regained consciousness he discovered that the man standing next to him, Sergeant Harry Ayres, had been killed by the same shell that had wounded him.

Lewis was able to crawl away and was picked up by two stretcher-bearers. He was taken to a Casualty Clearing Station but although badly wounded his life was not in danger. Lewis was sent back to a hospital in Bristol where he made a slow recovery. Just after he arrived he wrote a letter to his father: "Nearly all my friends in the Battalion are gone. Did I ever mention Johnson who was a scholar of Queen's? I had hoped to meet him at Oxford some day, and renew the endless talks that we had out there ...I had had him so often in my thoughts, had so often hit on some new point in one of our arguments, and made a note of things in my reading to tell him when we met again, that I can hardly believe he is dead. Don't you find it particularly hard to realise the death of people whose strong personality makes them particularly alive?"

Lewis remained in hospital until October, 1918 and was demobbed two months later. He never fully recovered from his wounds and suffered from headaches and breathing problems for the rest of his life. He also had recurring nightmares: "On the nerves there are... effects which will probably go with quiet and rest... nightmares - or rather the same nightmare over and over again."

In 1919 Lewis took up his scholarship to Oxford University where he read classics and philosophy. He went to live with Jane Moore, the mother of Ernest Moore. He therefore kept the promise he had made in 1917 that he would look after his mother if he was killed in the First World War.

In 1925 Lewis became a fellow of Magdalen College, where he soon developed a reputation as an outstanding teacher. He published a series of books on philosophy including The Pilgrim Regress (1933), and The Allegory of Love (1936). Lewis also produced a science fiction trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1939) and That Hideous Strength (1945).

Lewis continued to live with Jane Moore in an house at Headington, overlooking Oxford in the river valley below. Moore developed dementia after the Second World War and was eventually moved into a nursing home, where she died in 1951.

Lewis is best known for "Narnia" stories for children that began with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) and finished with The Last Battle (1956). One critic argued that these books combined "strong imagination and lively adventure with artfully concealed Christian parable".

In 1954 Lewis became Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English at Cambridge University. His autobiography, Surprised By Joy, was published in 1955.

For several years Lewis corresponded with Joy Davidman, an American poet. The couple were married on 21st March 1956. She died from bone cancer on 13th July, 1960. Lewis wrote about the relationship in his book, A Grief Observed (1961).

Clive Staples Lewis died of kidney disease on 22nd November, 1963, the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Primary Sources

(1) C. S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy (1955)

I passed through the ordinary course of training (a mild affair in those days compared with that of the recent war) and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Somerset Light Infantry, the old XIII th Foot. I arrived in the front line trenches on my nineteenth birthday (November 1917), saw most of my service in the villages before Arras - Fampoux and Monchy - and was wounded at Mt Bernenchon, near Lillers, in April 1918.

I am surprised that I did not dislike the Army more. It was, of course, detestable. But the words "of course" drew the sting. That is where it differed from Wyvern. One did not expect to like it. Nobody said you ought to like it. Nobody pretended to like it. Everyone you met took it for granted that the whole thing was an odious necessity, a ghastly interruption of rational life. And that made all the difference. Straight tribulation is easier to bear than tribulation which advertises itself as pleasure.

(2) C. S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy (1955)

In my own battalion also I was assailed. Here I met one Johnson (on whom be peace) who would have been a lifelong friend if he had not been killed. He was, like me, already a scholar of an Oxford college (Queen's) who hoped to take up his scholarship after the war, but a few years my senior and at that time in command of a company. In him I found dialectical sharpness such as I had hitherto known only in Kirk, but coupled with youth and whim and poetry. He was moving towards Theism and we had endless arguments on that and every other topic whenever we were out of the line. But it was not this that mattered. The important thing was that he was a man of conscience. I had hardly till now encountered principles in anyone so nearly of my own age and my own sort. The alarming thing was that he took them for granted. It crossed my mind for the first time since my apostasy that the severer virtues might have some relevance to one's own life. I say "the severer virtues" because I already had some notion of kindness and faithfulness to friends and generosity about money - as who has not till he meets the temptation which gives all their opposite vices new and more civil names? But it had not seriously occurred to me that people like ourselves, people like Johnson and me who wanted to know whether beauty was objective.

(3) C. S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy (1955)

The war itself has been so often described by those who saw more of it than I that I shall say here little about it. Until the great German attack came in the Spring we had a pretty quiet time. Even then they attacked not us but the Canadians on our right, merely "keeping us quiet" by pouring shells into our line about three a minute all day. I think it was that day I noticed how a great terror overcomes a less: a mouse that I met (and a poor shivering mouse it was, as I was a poor shivering man) made no attempt to run from me. Through the winter, weariness and water were our chief enemies. I have gone to sleep marching and woken again and found myself marching still. One walked in the trenches in thigh gum boots with water above the knee; one remembers the icy stream welling up inside the boot when you punctured it on concealed barbed wire. Familiarity both with the very old and the very recent dead confirmed that view of corpses which had been formed the moment I saw my dead mother. I came to know and pity and reverence the ordinary man: particularly dear Sergeant Ayres, who was (I suppose) killed by the same shell that wounded me. I was a futile officer (they gave commissions too easily then), a puppet moved about by him, and he turned this ridiculous and painful relation into something beautiful, became to me almost like a father. But for the rest, the war - the frights, the cold, the smell of H. E. (high explosives), the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles, the sitting or standing corpses, the landscape of sheer earth without a blade of grass, the boots worn day and night till they seemed to grow to your feet - all this shows rarely and faintly in memory. It is too cut off from the rest of my experience and often seems to have happened to someone else. It is even in a way unimportant. One imaginative moment seems now to matter more than the realities that followed. It was the first bullet I heard - so far from me that it "whined" like a journalist's or a peace-time poet's bullet. At that moment there was something not exactly like fear, much less like indifference: a little quavering signal that said, " This is War. This is what Homer wrote about."

(4) C. S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy (1955)

Just after I was hit, I found (or thought I found) that I was not breathing and concluded that this was death. I felt no fear and certainly no courage. It did not seem to be an occasion for either. The proposition "Here is a man dying" stood before my mind as dry, as factual, as unemotional as something in a textbook. It was not even interesting.

(5) A. N. Wilson, C. S. Lewis (2005)

That he fell in love with Mrs Moore, and she with him - probably during the period when she was visiting him in hospital, and frantic with worry about Paddy - cannot be in doubt. Neither of them was a Christian believer, nor were they bound by any code of morality which would have forbidden them to become lovers in the fullest sense of the word. True, she was still married to the Beast, and would go on being married to him for the duration of her long association with C. S. Lewis. While nothing will ever be proved on either side, the burden of proof is on those who believe that Lewis and Mrs Moore were not lovers - probably from the summer of 1918 onwards. "When I came first to the University," Lewis tells us with typical hyperbole, "I was as nearly without a moral conscience as a boy could be ... of chastity, truthfulness and self-sacrifice, I thought as a baboon thinks of classical music.''