Katherine Mansfield

Kathleen (Katherine) Mansfield Beauchamp, the daughter of Harold Beauchamp (1858–1938) and Anne Burnell Dyer (1864–1918), was born in Wellington, New Zealand, on 14th October 1888. Her father was a very successful businessman and in 1893 he bought a country house at Karori, where Mansfield attended primary school. She then moved onto Wellington High School where she began writing stories.

In 1903 Beauchamp took his three elder daughters to educated at Queen's College, the school founded by Frederick Denison Maurice. Encouraged by her teachers, Mansfield began reading the work of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and Leo Tolstoy. She also edited the college magazine.

Katherine Mansfield reluctantly went home to New Zealand. She continued to write and had some stories published in The Native Companion . She also had a love affair with a young woman artist, Edith Bendall. On 1st June, 1907, she wrote in her journal: "Last night I spent in her arms - and tonight I hate her - which being interpreted, means that I adore her; that I cannot lie in my bed and not feel the magic of her body. I feel more powerfully all those so-termed sexual impulses with her than I have with any man. She enthrals, enslaves me - and her personal self - her body absolute - is my worship." She later wrote about a lesbian relationship in the short story Leves Amores .

Her relationship with Bendall upset her parents and in July 1908 they agreed that she could go and live in England. At first she rented a room in a hostel for young women in Warwick Crescent, Paddington. Soon afterwards Mansfield became involved with a young musician Garnet Trowell. She became pregnant by him, but soon parted from him, and married George Bowden (1877–1975), on 2nd March 1909. Soon afterwards she left her husband to live with Ida Baker. According to her biographer, Claire Tomalin: "Hearing of the marriage, Mrs Beauchamp crossed the world to investigate, warning Ida's family about lesbianism and taking Kathleen straight off to a Bavarian spa, Bad Wörishofen. Here she abandoned Kathleen and returned to Wellington, where she disinherited her. Her father, however, continued to pay her allowance, and over the years increased it to £300 per annum."

Her next lover was Floryan Sobienowski. She suffered a miscarriage and in 1910 she became seriously ill with the effects of untreated gonorrhoea. An operation left her unable to have children. Mansfield continued to write and in 1911 she had some short stories published in The New Age. Later that year, her first collection of stories appeared In a German Pension .

In 1912 Mansfield met John Middleton Murry . The couple began living together and Murry began publishing her work in an avant-garde magazine, Rhythm , that he was editing. Vanessa Curtis has pointed out: "Katherine felt superior towards them (men), and had been promiscuous since her late teens, frequently using men for her own pleasure and then moving on once the initial thrill had faded. She fell in love quickly, but until Murry entered the picture, seemed not to possess the stamina needed to develop a relationship more lasting and meaningful."

Mansfield disliked the traditional role played by women at this time. She wrote in her journal: "I hate hate hate doing these things that you accept just as all men accept of their women... I walk about with a mind full of ghosts of saucepans and primus stoves.... I loathe myself, today. I detest this woman who superintends you and rushes about, slamming doors and slopping water - all untidy with her blouse out and her nails grimed. I am disgusted and repelled by the creature that shouts at you, You might at least empty the pail and wash out the tea-leaves! Yes, no wonder you come over silent."

Mansfield and Murry became close friends with D. H. Lawrence. They were witnesses for the wedding of Lawrence and Frieda von Richthofen in 1914. The two couples established themselves in two cottages near Chesham in Buckinghamshire. According to Claire Tomalin: "Mansfield's reminiscences of New Zealand probably inspired Lawrence with the lesbian episode in The Rainbow (written in winter 1914–15), and she was certainly the model for Gudrun in Women in Love." Later, Mansfield and Murry joined the Lawrences at Higher Tregerthen, near Zennor, in an attempt at communal living. It was a failure and within weeks she and Murry moved on.

Mansfield also became friendly with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell. In 1915 the Morrells purchased Garsington Manor near Oxford and it became a meeting place for left-wing intellectuals. This included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Dorothy Brett, Siegfried Sassoon, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Ethel Smyth, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Herbert Asquith, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

In the autumn of 1915 Mansfield joined forces with D.H. Lawrence and John Middleton Murry to establish a new magazine called The Signature . Claire Tomalin, the author of Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987) has argued that it was decided "to sell by subscription; it was to be printed in the East End, and the contributors were to have a club room in Bloomsbury for regular meetings and discussions." Sales were poor and the magazine folded after three issues.

In 1916 Mansfield met Lytton Strachey at Garsington. After she told him she had been very impressed by The Voyage Out, a novel written by his great friend, Virginia Woolf . Strachey knew that Woolf had admired Mansfield's collection of short stories, In a German Pension , and arranged an introduction and the two women had dinner together at Hogarth House in Richmond. This was followed by a weekend together at Woolf's rented home, Asheham House, at Beddingham, near Lewes. Mansfield wrote to Woolf: "It was good to have time to talk to you; we have got the same job, Virginia, and it is really very curious and thrilling that we should both, quite apart from each other, be after so very nearly the same thing."

Mansfield also became friendly with Ottoline Morrell , Dorothy Brett , Dora Carrington and Bertram Russell . According to Claire Tomalin: "She made a conquest of Lady Ottoline Morrell and friends of two women painters she met there, Dorothy Brett and (Dora) Carrington; later in the year she shared a house with them in London at 3 Gower Street. There was a flirtation with Bertrand Russell, and Lytton Strachey was impressed by her." During this period she left Murry and went to live with Ida Baker in Kensington.

Mark Gertler claimed that at one of the parties at Garsington Manor he "made violent love to Katherine Mansfield! She returned it, also being drunk. I ended the evening by weeping bitterly at having kissed another man's woman and everyone was trying to console me. Mansfield told Frieda Lawrence that she was in love with Gertler. Frieda accused Mansfield of leading the younger man on, and threatened never to speak to her again.

Dora Carrington became especially close to Mansfield. In a letter Carrington wrote to Lytton Strachey on 6th September 1916 she explained how she was hoping to set up home with Mansfield and Dorothy Brett : "Late Tuesday evening I bicycled over to Garsington to see Dorothy Brett about this house business, & Katherine Mansfield was there. I shared a room with her. So talked to her more than anyone else late at night in bed & early in the morning. I like her very much. It is a good thought to think upon that I shall live with them & Brett ... What parties we shall have in Gower Street in the evenings. Katherine was full of plans... Except for Katherine I should not have enjoyed it much. But she surprised me I did not believe she would love the sort of things I do so much. Pretending to be other people & playing games & all those strange people with their intrigues .. . Katherine and I wore trousers. It was wonderful being alone in the garden. Hearing the music inside, & lighted windows and feeling like two young boys - very eager. The moon shining on the pond, fermenting & covered with warm slime. How I hate being a girl. I must tell you for I have felt it so much lately. More than usual. And that night I forgot for almost half an hour in the garden, and felt other pleasures strange, & so exciting, a feeling of all the world being below me to choose from. Not tied - with female encumbrances, & hanging flesh."

Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf encouraged Mansfield to finish Prelude , which they were eager to publish with the Hogarth Press, the small publishing firm they had just founded. Leonard described her as "an intense realist, with a superb sense of ironic humour". Hermione Lee has argued that "its fragmenting of a whole family history into intense, solipsistic moments of experience, its funny child's eye view, its brilliant tiny coloured details, its fluid movement between banal realities and inner fantasy, its satirical opposition of the female and male point of view, its sexual pain" had a major influence on Virginia. The critic, Vanessa Curtis , has pointed out: "Prelude, her story about a family moving to the country, told in short sketches through the eyes of one family member after another; it is a long story, related with clarity and humour... on publication, it was a great success and sold out very quickly."

Ottoline Morrell later recalled: "I think she (Katherine Mansfield) found it very difficult to be real, for she was naturally an actress. She took on parts so easily that she didn't know what she was herself... she had cheap taste... as a companion she was intoxicating... she wasn't a fraud - she was more of an adventuress."

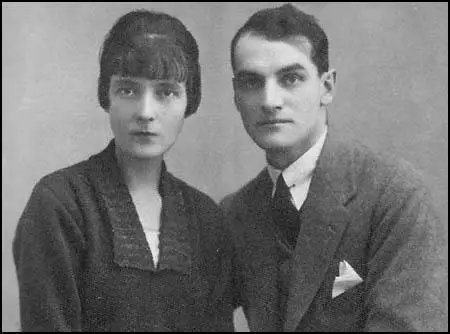

Katherine Mansfield became very ill and in December 1917 tuberculosis was diagnosed, and she was told she must go to a warmer climate. She settled in Bandol on the south coast of France. In January 1918, she suffered her first haemorrhage. She now decided to return to London and on 3rd May 1918 she married John Middleton Murry at Kensington Register Office. They rented a house close to Hampstead Heath, and Mansfield persuaded Ida Baker to give up her job and become their housekeeper.

John Middleton Murry was now editor of The Athenaeum, where he championed modernism in literature and provided a platform for the work of writers such as Katherine Mansfield, George Santayana, Paul Valéry, D. H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, E. M. Forster, T. S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. In 1922 he published his most important work, The Problems of Style.

Murray helped Mansfield's work to become known to the reading public. Vanessa Curtis , the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) : "Ironically, as Katherine began to blossom as a writer and receive serious recognition for her work, her health began to slip away, firstly with a recurrence of gonorrhoea and then with the onset of the tuberculosis that was to kill her. Photographs record her plumpness falling away from her bones, her body becoming gaunt, her eyes looking eerily big and scared in a pale, drawn face. She was forced, by the dangers of wintering in cold England, to go to the south of France, alone and away from Murry."

Murry gave Mansfield work reviewing fiction for The Athenaeum , and he negotiated the publication of her second collection, Bliss and other Stories, with Constable, in December 1920. The publication of her third collection, The Garden Party and other Stories, in February 1922 brought her, according to Claire Tomalin , "great and deserved acclaim." Later that month she went to Paris, where a Russian doctor was offering a new treatment for tuberculosis by irradiating the spleen with X-rays. She told Dorothy Brett : "If I were a proper martyr I should begin to have that awful smile that martyrs in the flames put on when they begin to sizzle". On her return she went to live with Brett in Hampstead.

Mansfield knew she was dying and wrote in her journal: "My spirit is nearly dead. My spring of life is so starved that it's just not dry. Nearly all my improved health is pretence - acting". She added that she hoped she would live long enough to enjoy "a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music and life."

Alfred Richard Orage, the editor of The New Age, told Mansfield about the ideas of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, a Greek-Armenian guru with a new establishment, the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, at Fontainebleau. In October 1922 Ida Baker accompanied Mansfield to the clinic but was then sent away. John Middleton Murry visited her on 9th January 1923. That evening as she went up the stairs she began to cough, a haemorrhage started, she said "I believe… I'm going to die" and according to Murry she was dead within minutes. On 12th January Mansfield was buried in the nearby cemetery at Avon. Only Murry, Baker, Dorothy Brett , and two of her sisters went to the funeral.

In her will she left the following instructions: "All manuscripts notebooks papers letters I leave to John M. Murry likewise I should like him to publish as little as possible and tear up and burn as much as possible he will understand that I desire to leave as few traces of my camping ground as possible."

After her death two further collections of short stories were published: The Dove's Nest (1923) and Something Childish (1924). John Middleton Murry edited and arranged for the publication of her Journals (1927) and The Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1928). According to Claire Tomalin: "Murry inherited her manuscripts and over the next two decades he edited and published almost all her remaining stories and fragments, her journals, her poems, her reviews, and her letters. In doing so he presented to the world an image of a saintly young woman and suppressed the darker aspects of her character and experience, perhaps understandably, given the conventions of the time. He also made a good income out of her considerable royalties. Not a penny went to Ida Baker."

Dora Carrington wrote after her death: "Her writing was the least interesting part of he... Even Lytton Strachey was impressed by her. She was so witty, & had so much courage. She lived every sort of life. She knew every sort of person. It was queer that she wrote so dully. For she was the reverse of that when one talked to her. I always think she was doomed through her connection with Murry. I think he ate her soul out of her."

Primary Sources

( 1) Dora Carrington , letter to Lytton Strachey (6th September 1916)

Late Tuesday evening I bicycled over to Garsington to see Dorothy Brett about this house business, & Katherine Mansfield was there. I shared a room with her. So talked to her more than anyone else late at night in bed & early in the morning. I like her very much. It is a good thought to think upon that I shall live with them & Brett ... What parties we shall have in Gower Street in the evenings. Katherine was full of plans. She was splendid at a concert there was at Garsington and sang coon songs, & acted a play. It was a curious night all very strange. I am out of favour now! Completely! I do not know why - But her ladyship loves and fondles me no more! and Brett was rather severe. I got rather lonely & depressed there.

Except for Katherine I should not have enjoyed it much. But she surprised me I did not believe she would love the sort of things I do so much. Pretending to be other people & playing games & all those strange people with their intrigues .. . Katherine and I wore trousers. It was wonderful being alone in the garden.

Hearing the music inside, & lighted windows and feeling like two young boys - very eager. The moon shining on the pond, fermenting & covered with warm slime.

How I hate being a girl. I must tell you for I have felt it so much lately. More than usual. And that night I forgot for almost half an hour in the garden, and felt other pleasures strange, & so exciting, a feeling of all the world being below me to choose from. Not tied - with female encumbrances, & hanging flesh.

( 2) Claire Tomalin ,New Statesman(1971)

John Middleton Murry published every scrap he could find, and her tigerish desire for privacy was sacrificed to please a public avid to sift through her secrets. But who can blame him? She was a genius, of the kind who provokes both worthy and unworthy curiosity, both the prurient wish to hear of the ill health and sexual practices of the mighty, and the abiding and educative human craving to try to enter into the minds of those we admire, to become them for a space (and I suspect the two kinds of curiosity are inextricably blended). What fury fills us when we think of the pious executors and grandchildren who burn letters and memoirs to protect the good name of the dead...

Early in their friendship, which started at Queen's College, Harley Street, in 1903, Ida Baker dedicated herself to the service of Katherine, perceiving, although there was never much intellectual rapport, that she was an exceptional person and soon realizing that she needed the sort of help that could come only from a friend who put no value on her own affairs or time. Throughout Katherine's life Ida Baker came when she was summoned and disappeared again (sometimes reluctantly) when dismissed, gave up her jobs, took on domestic work that was totally uncongenial and endured scoldings and ridicule. She was mocked to her face and cruelly dealt with in letters, the journal and even stories. Why did she endure it?

Obviously she loved Katherine passionately, and the relationship was more complex than a simple served and serving one; Katherine felt that Ida was too emotionally dependent on her, hence the "incubus" accusation; but she was dependent too, and could be jealous: "I only love you when you're blind to everybody but us." To say that it was a lesbian attachment does not explain much; Ida points out that Katherine's first husband considered that this was the cause of the break-up of the marriage, and mentions that she did not even know what lesbianism was at that time. Katherine's mother thought the friendship "unwise" too, in a euphemism familiar to anyone who has been at a girls' school; in fact Katherine was pregnant by another man when she married. Katherine herself certainly knew what lesbianism was, as her journal makes clear, and was capable of flirting with either sex, but she was never in love with Ida in the way she was with Murry or Francis Carco; only she enjoyed her power of attracting and enslaving, and then felt guilty and irritated by the humble, fussy adoration.

(3) Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington (1989)

Carrington knew of Gertler's homophobia (very likely encouraged both by her growing friendship with Strachey and by Gertler's friendship with D. H. Lawrence, a notorious homophobic), and this letter indicates both her dawning recognition of her own bisexuality as well as a plea for a neutral and all-encompassing androgyny. Mansfield was herself bisexual, but there is no indication that their relationship became a physical one. Mansfield allowed Carrington to express her concerns about her sexuality without necessarily encouraging her to act them out. Others in Bloomsbury apparently recognised this aspect of Carrington for, twelve years after Carrington posed nude, simulating a statue, for a photograph in Garsington, Vanessa Bell painted a panel entitled Bacchanale, featuring a figure astonishingly similar to it with one important exception: the figure is clearly an hermaphrodite. Bloomsbury's sexual relationships crossed lines Carrington in her youth assumed to be firm. Maynard Keynes had relationships with men before marrying in middle age; Duncan Grant, despite fathering a child with Vanessa Bell, was primarily homosexual and had an affair with David Garnett who later married Duncan and Vanessa's daughter Angelica; Virginia and Leonard Woolf had a celibate marriage; Lytton was, of course, homosexual and continued to have affairs with men despite his relationship with Carrington.

(4) Virginia Woolf , The Essays of Virginia Woolf (1986)

No one felt more seriously the importance of writing than she did. In all the pages of her journal, instinctive, rapid as they are, her attitude to her work is admirable; sane, caustic, and austere. There is no literary gossip; no vanity; no jealousy. Although during her last years she must have been aware of her success she makes no allusion to it. Her own comments upon her work are always penetrating and disparaging. Her stories wanted richness and depth ... Under the desperate pressure of increasing illness she began a curious difficult search.

(5) Hermione Lee , Virginia Woolf (1996)

In the autumn of 1917 Katherine Mansfield developed the first symptoms of consumption; she was very ill, and had to leave the country for the first of many lonely winters abroad. She was extremely wretched, and over the winter she began to turn against her patrons in Garsington and Bloomsbury (the Bloomsbury tangi, she called them - a Maori word for wailing mourners at a funeral). She had been delighted that Virginia and Leonard wanted Prelude (the New Zealand story she had cut down for them from a longer version called The Aloe). "I threw my darling to the wolves," she told her friend Dorothy Brett, "and they ate it and served me up so much praise in a golden bowl that I couldn't help feeling gratified." But it seemed to be taking them a very long time to digest: "I think the Woolfs must have eaten the Aloe root and branch or made jam of it," she wrote to Ottoline in February 1918. "I'm sorry you have to go to the Woolves," she wrote to Murry in the same week. "I don't like them either. They are smelly." But at just this time Virginia was thinking of Katherine as one of the few people she could discuss her work with. Inevitably, Katherine was on her mind, since almost every day during these winter months of the war, while she was writing her own novel, she was setting Prelude.

(6) Vanessa Curtis , Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

Ironically, as Katherine began to blossom as a writer and receive serious recognition for her work, her health began to slip away, firstly with a recurrence of gonorrhoea and then with the onset of the tuberculosis that was to kill her. Photographs record her plumpness falling away from her bones, her body becoming gaunt, her eyes looking eerily big and scared in a pale, drawn face. She was forced, by the dangers of wintering in cold England, to go to the south of France, alone and away from Murry. Her letters to him over the next three months reveal her insecurities and her bravery over illness, but also her insensitivity and selfishness. Devoted Ida Baker, arriving in France to help Katherine, was accused of being overweight, greedy and stupid. Indeed, next to Katherine, who existed on nothing other than cigarettes and coffee, it is hardly surprising that anyone else was considered gluttonous by comparison! Katherine's harshness extended into her letters to Murry, where she viciously attacked poor Ottoline Morrell while at the same time sending the subject of this wrath the most flattering, false letters of adoration. This situation was further complicated by the fact that Murry considered himself to be temporarily in love with Ottoline, but all the while kept up the charade of distaste in his replies to Katherine.

After three months in France, during which time she became even more unwell, Katherine decided that the separation from Murry was too painful to bear any longer, and came home. She was to be disappointed at their reunion; Murry, rather than embrace her with the passion she needed, turned his face aside, fearfully covering his mouth to avoid infection.

(7) Dora Carrington, letter to Gerald Brenan (20th December 1922)

I have the greatest contempt for people like Middleton Murry and Katherine Murry who think it is "interesting" to be ill and who sniff up their noses at any writer who hasn't cancer in the stomach, or violent consumption.

(8) Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

In January 1923, Katherine Mansfield died of tuberculosis in France. Carrington, who had not seen her since they had shared the house on Gower Street, described her to Gerald as a great life-enhancer. "Her writing was the least interesting part of he ... Even Lytton Strachey was impressed by her. She was so witty, & had so much courage. She lived every sort of life. She knew every sort of person. It was queer that she wrote so dully. For she was the reverse of that when one talked to her. I always think she was doomed through her connection with Murry. I think he ate her soul out of her." She later added that she was "very much a female of the underworld, with the language of a fishwife in Wapping. Murry's circle in Hampstead is now making her into a mystical Keats."