The Commonwealth: 1648-1660

In January 1649, King Charles I was charged with "waging war on Parliament." It was claimed that he was responsible for "all the murders, burnings, damages and mischiefs to the nation" in the English Civil War. The jury included members of Parliament, army officers and large landowners. Some of the 135 people chosen as jurors did not turn up for the trial. For example. General Thomas Fairfax, the leader of the Parliamentary Army, did not appear. When his name was called, a masked lady believed to be his wife, shouted out, "He has more wit than to be here." (1)

This was the first time in English history that a king had been put on trial. Charles believed that he was God's representative on earth and therefore no court of law had any right to pass judgement on him. Charles therefore refused to defend himself against the charges put forward by Parliament. Charles pointed out that on 6th December 1648, the army had expelled several members of' Parliament. Therefore, Charles argued, Parliament had no legal authority to arrange his trial. The arguments about the courts legal authority to try Charles went on for several days. Eventually, on 27th January, Charles was given his last opportunity to defend himself against the charges. When he refused he was sentenced to death. His death warrant was signed by the fifty-nine jurors who were in attendance. (2)

On the 30th January, 1649, Charles was taken to a scaffold built outside Whitehall Palace. Charles wore two shirts as he was worried that if he shivered in the cold people would think he was afraid of dying. He told his servant "were I to shake through cold, my enemies would attribute it to fear." Troopers on horseback kept the crowds some distance from the scaffold, and it is unlikely that many people heard the speech that he made just before his head was cut off with an axe. The executioner then took up the head and announced, in traditional fashion, "Behold the head of a traitor!" At that moment, according to an eyewitness, "there was such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again." (3)

The Commonwealth

The House of Commons now passed a series of new laws. They abolished the monarchy, on the grounds that it was "unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interest of the people" and the House of Lords as "it is useless and dangerous to the people of England". Lands owned by the royal family and the church were sold and the money was used to pay the parliamentary soldiers. People were no longer fined for not attending their local church. However, everyone was still expected to attend some form of religious worship on Sundays. The country was now declared to be a "Commonwealth and Free State" under the rule of Parliament, and the government was entrusted to a Council of State, under the provisional chairmanship of Oliver Cromwell. (4)

The Levellers wanted Parliament to pass reforms that would increase universal suffrage. Soldiers also continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed.

Lockyer's funeral on Sunday 29th April, 1649, proved to be a dramatic reminder of the strength of the Leveller organization in London. "Starting from Smithfield in the afternoon, the procession wound slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the interment in New Churchyard. Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons - black for mourning and sea-green to publicize their Leveller allegiance. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous autumn." (5)

John Lilburne continued to campaign against the rule of Oliver Cromwell. According to a Royalist newspaper at the time: "He (Cromwell) and the Levellers can as soon combine as fire and water... The Levellers aim being at pure democracy.... and the design of Cromwell and his grandees for an oligarchy in the hands of himself." (6) Lilburne argued that Cromwell's government was mounting a propaganda campaign against the Levellers and to prevent them from replying their writings were censored: "To prevent the opportunity to lay open their treacheries and hypocrisies... the stop the press... They blast us with all the scandals and false reports their wit or malice could invent against us... By these arts are they now fastened in their powers." (7)

David Petegorsky, the author of Left-Wing Democracy in the English Civil War (1940) has pointed out: "The Levellers clearly saw, that equality must replace privilege as the dominant theme of social relationships; for a State that is divided into rich and poor, or a system that excludes certain classes from privileges it confers on others, violates that equality to which every individual has a natural claim." (8)

In May 1649 another Leveller-inspired mutiny broke out at Salisbury. Led by Captain William Thompson, they were defeated by a large army at Burford led by Major Thomas Harrison. Thompson escaped only to be killed a few days later near the Diggers community at Wellingborough. After being imprisoned in Burford Church with the other mutineers, three other leaders, "Private Church, Corporal Perkins and Cornett Thompson", were executed by Cromwell's forces in the churchyard. (9) John Lilburne responded by describing Harrison as a "hypocrite" for his initial encouragement of the Levellers. (10)

Ireland

Oliver Cromwell was asked by Parliament to take control of Ireland. The country had caused serious problems for English generals in the past so Cromwell was careful to make painstaking preparations before he left. Cromwell ensured that the wage arrears of his army were paid, and that he was guaranteed sufficient financial provision by parliament. On 15th August 1649, Cromwell arrived in Ireland and took control of an army of 12,000 men. (11) Cromwell made a speech to the Irish people the following day: "God has brought us here in safety... We are here to carry on the great work against the barbarous and blood-thirsty Irish... to propagate the Gospel of Christ and the establishment of truth... and to restore this nation to its former happiness and tranquillity." (12)

Cromwell, like nearly all Puritans "had been inflamed against the Irish Catholics by the true and false allegations of the atrocities which they had committed against English Protestants settlers during the Irish Catholic rebellion of 1641." (13) He wrote at the time that "all the world knows their barbarism". Even the philosopher, Francis Bacon, and the poet John Milton, who "believed passionately in liberty and human dignity", shared the view that "the Irish were culturally so inferior that their subordination was natural and necessary." (14)

Cromwell's first action on reaching Ireland was to forbid any plunder or pillage - an order that could not have been enforced with an unpaid army. Two men were hanged for plundering to convince the soldiers he was serious about this order. To control Dublin's northern approaches Cromwell needed to take the port of Drogheda. Once in his hands he could feel confident of controlling the whole of the northern route from Dublin to Londonderry. On 3rd September, around 12,000 men and supporting vessels had arrived outside the town. Surrounding the whole town was a massive wall, 22 feet high and 6 feet thick.

Sir Arthur Aston, who had been fighting for the royalists during the English Civil War, was the governor of Drogheda. On 10th September, Cromwell advised Aston to surrender. "I have brought the army belonging to the Parliament of England to this place, to reduce it to obedience... if you surrender you will avoid the loss of blood... If you refuse... you will have no cause to blame me." (15)

Cromwell had four times as many men as Aston and was better supplied with weapons, stores and equipment. Cromwell's proposal was rejected and the garrison opened fire with what weapons they had. Cromwell's reply was to attack the city wall and by nightfall two breaches had been made. The following day Cromwell led his soldiers into Drogheda.

Aston and some 300 soldiers climbed Mill Mount. Cromwell's troops surrounded the men and it was usually the custom to allow them to surrender. However, Cromwell gave the order to kill them all. Aston's head was beaten in with his own wooden leg. Cromwell instructed his men to kill all the soldiers in the town. About eighty men had taken refuge in St Peter's Church. It was set on fire and all the men were killed. All the priests that were captured were also slaughtered. (16)

Cromwell sent a letter to William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons: "I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbued their hands in so much innocent blood; and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are the satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret." (17)

The response from Parliament was that they were unwilling to pay for a long war. He was told to take control of the large estates owned by Catholics and to sell or rent it to Protestants. This money was to be used to pay his soldiers. Cromwell decided that the best way to bring a quick end to the war was to carry out another massacre. After an eight days' siege at Wexford, around 1,800 troops, priests and civilians were butchered. (18)

Hugh Peter, a chaplain to the Parliamentary army and a passionate anti-Catholic, was with Cromwell in Ireland. He reported that the town was now available for English Protestant colonists to settle. "It is a fine spot for some godly congregation, where house and land wait for inhabitants and occupiers." (19)

During the next few years of bloodshed it is estimated that about a third of the population was either killed or died of starvation. The majority of Roman Catholics who owned land had it taken away from them and were removed to the barren province of Connacht. Catholic boys and girls were shipped to Barbados and sold to the planters as slaves. The land taken from the Catholics by Cromwell was given to the Protestant soldiers who had taken part in the campaign. Before the rebellion in 1641, Catholics owned 59% of the land in Ireland. By the time Cromwell left in 1650 the proportion had shrunk to 22%. (20)

Oliver Cromwell and the Radicals

On 9th March, 1649, the House of Lords was abolished. (21) Although the House of Commons continued to meet, it was Cromwell and his followers who controlled England. The Levellers continued to campaign for an increase in the number of people who could vote. John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince, all served terms of imprisonment. On 20th September, 1649, Parliament passed a law introducing government censorship. It now required a licence for the publication of any book, pamphlet, treatise or sheets of news. As Pauline Gregg has pointed out that the situation was little different "from the censorship they had been fighting in the King's time". (22)

On 24th October, 1649, Lilburne was charged with high treason. The trial began the following day. The prosecution read out extracts from Lilburne's pamphlets but the jury was not convinced and he was found not guilty. There were great celebrations outside the court and his acquittal was marked with bonfires. A medal was struck in his honour, inscribed with the words: "John Lilburne saved by the power of the Lord and the integrity of the jury who are judge of law as well of fact". On 8th November, all four men were released. (23)

Cromwell was also having problems with Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the group that became known as the Diggers. Winstanley began arguing that all land belonged to the community rather than to separate individuals. In January, 1649, he published the The New Law of Righteousness. In the pamphlet he wrote: "In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." (24)

Winstanley claimed that the scriptures threatened "misery to rich men" and that they "shall be turned out of all, and their riches given to a people that will bring forth better fruit, and such as they have oppressed shall inherit the land." He did not only blame the wealthy for this situation. As John Gurney has pointed out, Winstanley argued: "The poor should not just be seen as an object of pity, for the part they played in upholding the curse had also to be addressed. Private property, and the poverty, inequality and exploitation attendant upon it, was, like the corruption of religion, kept in being not only by the rich but also by those who worked for them." (25)

Winstanley claimed that God would punish the poor if they did not take action: "Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men, your oppressors by your labours... If you labour the earth, and work for others that live at ease, and follows the ways of the flesh by your labours, eating the bread which you get by the sweat of your brows, not their own. Know this, that the hand of the Lord shall break out upon such hireling labourer, and you shall perish with the covetous rich man." (26)

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them. (27) They sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". (28) Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. (29)

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." (30) Oliver Cromwell condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (31)

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark. (32)

© National Portrait Gallery

Cromwell also had problems with the Ranters. In 1650 Abiezer Coppe published A Fiery Flying Roll: A Word from the Lord to all the great ones of the Earth. In this pamphlet he claimed that "the Levellers (men-levellers) which is and who indeed are but shadows of most terrible, yet great and glorious good things to come". People who did not own property would have "treasure in heaven". His main message was that God, the "mighty leveller" would return to earth and punish those who did not share their wealth. Coppe argued for freedom, equality, community and universal peace. He told the wealthy that they would be punished for their lack of charity towards the poor: "The rust of your silver, I say, shall eat your flesh as it were fire... have... Howl, howl, ye nobles, howl honourable, howl ye rich men for the miseries that are coming upon you." (33) The historian, Alfred Leslie Rowse, claims that Coppe's "egalitarian Communism" was "300 years" before its time. (34)

Laurence Clarkson, had been a preacher in the New Model Army who wrote a pamphlet he defined the "oppressors" as the "nobility and gentry" and the oppressed as the "yeoman farmer" and the "tradesman". (35) Coppe and Clarkson both advocated "free love". (36) Peter Ackroyd claimed that Coppe and Clarkson professed that "sin had its conception only in imagination" and told their followers that they "might swear, drink, smoke and have sex with impunity". (37)

Barry Coward, the author of The Stuart Age: England 1603-1714 (1980) argues that the activities of the Ranters created a "moral panic" because their activities were "often violent and anti-social" and frightened conservative opinion into reaction. They formed a "hippy-like counter culture of the 1650s which flew in the face of law and morality and which was considered with horror by respectable society." (38) Cromwell disliked the Ranters more than any other religious sect who he considered to be totally immoral. (39)

Cromwell and his supporters in Parliament attempted to deal with preachers such as Coppe and Clarkson, by passing the Adultery Act (May 1650), that imposed the death penalty for adultery and fornication. This was followed by the Blasphemy Act (August 1650). Coppe claimed he had been informed that the acts against adultery and blasphemy "were put out because of me; thereby secretly intimating that I was guilty of the breach of them". (40) Christopher Hill, the author of The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991), agrees that this legislation was an attempt to deal with the development of religious groups such as the Ranters. (41)

Lord Protector

Oliver Cromwell became increasingly frustrated by the inability of Parliament to get anything done. His biographer, Pauline Gregg, has pointed out: "He realized that all revolutions are about power and he was asking himself who, or what, should exercise that power. He knew, moreover, that whoever or whatever was in control must be strong enough to propel the state in one direction. This he learned from his battle experience. To be successful an army must observe one plan, one directive." (42)

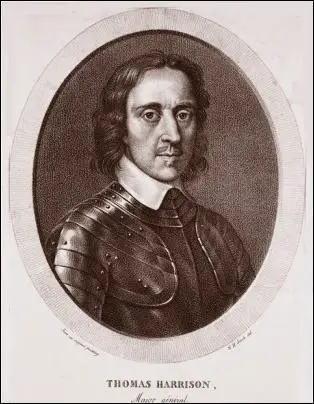

Major General Thomas Harrison, who had been sympathetic to the demands of the Levellers, urged the House of Commons to pass legislation to help the poor. In August 1652, he promoted an army petition that called for law reform, the more effective propagation of the gospel, the elimination of tithes, and speedy elections for a new parliament. When it failed to act on these items, Harrison began to press for its dissolution. Harrison argued that when it was established after the death of the Charles I it was "unanimous in its proceedings for the reform of the nation" but it was now dominated by "a strong Royalist party". (43)

On 20th April 1653, Cromwell sent in his troopers with their muskets and drawn swords into the House of Commons. Harrison himself pulled the Speaker, William Lenthall, out of the Chair and pushed him out of the Chamber. That afternoon Cromwell dissolved the Council of State and replaced it with a committee of thirteen army officers. Harrison was appointed as chairman and in effect the head of the English state. (44)

In July, 1653, Oliver Cromwell established the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints. The total number of nominees was 140, 129 from England, five from Scotland and six from Ireland. The nominated assembly grappled with several of Harrison's favourite issues, including the immediate abolition of tithes. There was general consensus that tithes were objectionable, but no agreement about what mechanism for generating revenue should replace them. (45)

The Parliament was closed down by Cromwell in December, 1653. Charles H. Simpkinson has argued that Harrison now believed that "England now lay under a military despotism". (46) This decision was fiercely opposed by Thomas Harrison. Cromwell reacted by depriving him of his military commission, and in February, 1654, he was ordered to retire to Staffordshire. However, he was able to keep the land he had acquired during his period of power. The total value of this land was well over £13,000. (47)

The army decided that Oliver Cromwell should become England's new ruler. Some officers wanted him to become king but he refused and instead took the title Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. However, Cromwell had as much power as kings had in the past. The franchise was restricted to those who possessed the very high property qualification of £200 and by the disqualification of all who had taken part in the English Civil War on the royalist side. (48)

When the House of Commons opposed his policies in January 1655, he closed it down. Cromwell always disliked the idea of democracy as he posed a threat to good government. "The mass of the population was totally unsophisticated politically, very much under the influence of landlords and parsons: to give such men the vote (with no secret ballot, since most of them were illiterate) would be to strengthen rather than to weaken the power of the conservatives." (49)

Richard Baxter attempted to explain Cromwell's thinking: "In most parts, the major vote of the vulgar... is ruled by money and therefore by their landlords." (50) Cromwell warned Parliament that the vast majority of the population was opposed to his government: "The condition of the people is such as the major part a great deal are persons disaffected and engaged against us." (51) One pamphlet published at the time commented "if the common vote of the giddy multitude must rule the whole" Cromwell's government would be overthrown. (52)

Cromwell now imposed military rule. England was divided into eleven districts. Each district was run by a Major General and were answerable only to the Lord Protector. Christopher Hill argues that "The Major-Generals were to make all men responsible for the good behaviour of their servants.... They also enforced the legislation of the Long Parliament against drunkenness, blasphemy and sabbath-breaking... Above all they took control of the militia, the army of the gentry." (53)

The first duty of the Major-Generals was to maintain security by suppressing unlawful assemblies, disarming Royalist supporters and apprehending thieves, robbers and highwaymen. The militia of the Major-Generals was funded by a new 10% income tax imposed on Royalists known as the "decimation tax". It was argued that a punitive tax on Royalists was a just means of financing the militia because Royalist conspiracies had made it necessary in the first place. (54)

The responsibilities of these Major-Generals included granting poor relief and imposing Puritan morality. In some districts bear-baiting, cock-fighting, horse-racing and wrestling were banned. Betting and gambling were also forbidden. Large numbers of ale-houses were closed and fines were imposed on people caught swearing. In some districts, the Major-Generals even closed down theatres. (55)

Former members of the Levellers grew disillusioned with the dictatorial policies of Cromwell and in 1655 Edward Sexby, John Wildman and Richard Overton were involved in developing a plot to overthrow the government. The conspiracy was discovered and the men were forced to flee to the Netherlands. It was later argued that Overton was by this time acting as a double agent and had informed the authorities of the plot. (56) Records show that Overton was receiving payments from Cromwell's secretary of state, John Thurloe. (57)

In May 1657 Sexby published, under a pseudonym, Killing No Murder, a pamphlet that attempted to justify the assassination of Oliver Cromwell. Sexby accused Cromwell of the enslavement of the English people and argued for that reason he deserved to die. After his death "religion would be restored" and "liberty asserted". He hoped "that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest". (58) The following month Edward Sexby arrived in England to carry out the deed, however, he was arrested on 24th July. He remained in the Tower of London until his death on 13th January 1658. (59)

In 1658 Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (60)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (61)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (62)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (63)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (64)

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and on the twelfth anniversary of the regicide, on 30th January 1661, their bodies were disinterred and hung from the gallows at Tyburn. (65) Cromwell's body was put into a lime-pit below the gallows and the head, impaled on a spike, was exposed at the south end of Westminster Hall for nearly twenty years. (66)

Primary Sources

(1) John Milton, The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1649)

Surely they that shall boast, as we do, to be a free nation, and not have in themselves the power to remove or to abolish any governor supreme, or subordinate, with the government itself upon urgent causes, may please their fancy with a ridiculous and painted freedom, fit to cozen babies; but are indeed under tyranny and servitude, as wanting that power which is the root and source of all liberty, to dispose and economise in the land which God hath given them, as masters of family in their own house and free inheritance. Without which natural and essential power of a free nation, though bearing high their heads, they can in due esteem be thought no better than slaves and vassals born, in the tenure and occupation of another inheriting lord, whose government, though not illegal or intolerable, hangs over them as a lordly scourge, not as a free government - and therefore to be abrogated.

Though perhaps till now no protestant state or kingdom can be alleged to have openly put to death their king, which lately some have written and imputed to their great glory, much mistaking the matter, it is not, neither ought to be, the glory of a Protestant state never to have put their king to death; it is the glory of a Protestant king never to have deserved death. And if the parliament and military council do what they do without precedent, if it appear their duty, it argues the more wisdom, virtue, and magnanimity, that they know themselves able to be a precedent to others; who perhaps in future ages, if they prove not too degenerate, will look up with honour and aspire towards these exemplary and matchless deeds of their ancestors, as to the highest top of their civil glory and emulation; which heretofore, in the pursuance of fame and foreign dominion, spent itself vaingloriously abroad, but henceforth may learn a better fortitude - to dare execute highest justice on them that shall by force of arms endeavour the oppressing and bereaving of religion and their liberty at home: that no unbridled potentate or tyrant, but to his sorrow, for the future may presume such high and irresponsible licence over mankind, to havoc and turn upside down whole kingdoms of men, as though they were no more in respect of his perverse will than a nation of pismires.

(2) John Lilburne, Richard Overton and Thomas Prince, Englands New Chains Discovered (March, 1649)

If our hearts were not over-charged with the sense of the present miseries and approaching dangers of the Nation, your small regard to our late serious apprehensions, would have kept us silent; but the misery, danger, and bondage threatened is so great, imminent, and apparent that whilst we have breath, and are not violently restrained, we cannot but speak, and even cry aloud, until you hear us, or God be pleased otherwise to relieve us.

Removing the King, the taking away the House of Lords, the overawing the House, and reducing it to that pass, that it is become but the Channel, through which is conveyed all the Decrees and Determinations of a private Council of some few Officers, the erecting of their Court of Justice, and their Council of State, The Voting of the People of Supreme Power, and this House the Supreme Authority: all these particulars, (though many of them in order to good ends, have been desired by well-affected people) are yet become, (as they have managed them) of sole conducement to their ends and intents, either by removing such as stood in the way between them and power, wealth or command of the Commonwealth; or by actually possessing and investing them in the same.

They may talk of freedom, but what freedom indeed is there so long as they stop the Press, which is indeed and hath been so accounted in all free Nations, the most essential part thereof, employing an Apostate Judas for executioner therein who hath been twice burnt in the hand a wretched fellow, that even the Bishops and Star Chamber would have shamed to own. What freedom is there left, when honest and worthy Soldiers are sentenced and enforced to ride the horse with their faces reverst, and their swords broken over their heads for but petitioning and presenting a letter in justification of their liberty therein? If this be not a new way of breaking the spirits of the English, which Strafford and Canterbury never dreamt of, we know no difference of things.

(3) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

Kingly government governs the earth by that cheating art of buying and selling, and thereby becomes a man of contention his hand is against every man, and every man's hand against him. And take this government at the best, it is a diseased government and the very City Babylon, full of confusion, and if it had not a club law to support it there would be no order in it, because it is the covetous and proud will of a conqueror, enslaving the conquered people.

This kingly government is he who beats pruning hooks and ploughs into spears, guns, swords, and instruments of war; that he might take his younger brother's creational birth-right from him, calling the earth his, and not his brother's, unless his brother will hire the earth of him; so that he may live idle and at ease by his brother's labours.

Indeed this government may well be called the government of highwaymen, who hath stolen the earth from the younger brethren by force, and holds it from them by force. He sheds blood not to free the people from oppression, but that he may be king and ruler over an oppressed people....

Commonwealth's government governs the earth without buying and selling and thereby becomes a man of peace, and the restorer of ancient peace and freedom. He makes provision for the oppressed, the weak and the simple, as well as for the rich, the wise and the strong. He beats swords and spears into pruning hooks and ploughs. He makes both elder and younger brother freemen in the earth.

(4) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory. For though at first entrance into places of rule they be of public spirit, seeking the freedom of others as their own; yet continuing long in such a place, where honours and greatness is coming in, they become selfish, seeking themselves and not common freedom; as experience proves it true in these days, according to this common proverb, Great offices in a land and army have changed the disposition of many sweet-spirited men.

And nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use. Therefore as the necessity of common preservation moves the people to frame a law, and to choose officers to see the law obeyed, that they may live in peace: so doth the same necessity bid the people, and cries aloud in the ears and eyes of England, to choose new officers and to remove old ones, and to choose state officers every year.

The Commonwealth hereby will be furnished with able and experienced men, fit to govern, which will mightily advance the honour and peace of our land, occasion the more watchful care in the education of children, and in time will make our Commonwealth of England the lily among the nations of the earth.

(5) Oliver Cromwell commenting on the activities of the Levellers and the Diggers (1649)

What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces.

(6) John Milton, The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (1660)

If we prefer a free government, though for the present not obtained, yet all those suggested fears and difficulties, as the event will prove, easily overcome, we remain finally secure from the exasperated regal power, and out of snares; shall retain the best part of our liberty, which is our religion, and the civil part will be from these who defer us, much more easily recovered, being neither so subtle nor so awful as a king reinthroned. Nor were their actions less both at home and abroad, than might become the hopes of a glorious rising commonwealth: nor were the expressions both of army and people, whether in their public declarations or several writings, other than such as testified a spirit in this nation, no less noble and well-fitted to the liberty of a commonwealth, than in the ancient Greeks or Romans. Nor was the heroic cause unsuccessfully defended to all Christendom, against the tongue of a famous and thought invincible adversary; nor the constancy and fortitude, that so nobly vindicated our liberty, our victory at once against two the most prevailing usurpers over mankind, superstition and tyranny, unpraised or uncelebrated in a written monument, likely to outlive detraction, as it hath hitherto convinced or silenced not a few of our detractors, especially in part abroad.

After our liberty and religion thus prosperously fought for, gained, and many years possessed, except in those unhappy interruptions, which God hath removed; now that nothing remains, but in all reason the certain hopes of a speedy and immediate settlement for ever in a firm and Besides this, if we return to kingship, and soon repent (as undoubtedly we shall, when we begin to find the old encroachment coming on by little and little upon our consciences, which must necessarily proceed from king and bishop united inseparably in one interest), we may be forced perhaps to fight over again all that we have fought, and spend over again all that we have spent, but are never like to attain thus far as we are now advanced to the recovery of our freedom, never to have it in possession as we now have it, never to be vouchsafed hereafter the like mercies and signal assistances from Heaven in our cause, if by our ungraceful backsliding we make these fruitless; flying now to regal concessions from his divine condescensions and gracious answers to our once importuning prayers against the tyranny which we then groaned under; making vain and viler than dirt the blood of so many thousand faithful and valiant Englishmen, who left us this liberty, bought with their lives; losing by a strange after-game of folly all the battles we have won, together with all Scotland as to our conquest, hereby lost, which never any of our kings could conquer, all the treasure we have spent, not that corruptible treasure only, but that far more precious of all our late miraculous deliverances; treading back again with lost labour all our happy steps in the progress of reformation, and most pitifully depriving ourselves the instant fruition of that free government, which we have so dearly purchased, a free commonwealth.

(7) Edmund Ludlow, Memoirs of Edmund Ludlow (c. 1680)

In the mean time the Major-Generals carried things with unheard of insolence in their several precincts, decimating to extremity whom they pleased, and interrupting the proceedings at law upon petitions of those who pretended themselves aggrieved; threatening such as would not yield a ready submission to their orders, with transportation to Jamaica or some other plantations in the West Indies; and suffering none to escape their persecution, but those that would betray their own party, by discovering the persons that had acted with them or for them.

(8) Christopher Hill, God's Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution (1970)

After the failure of his first Parliament and some unsuccessful royalist and republican conspiracies in the early months of 1655, Oliver accepted his generals' scheme for direct military rule. The country was divided into eleven districts, and over each a Major-General was set, to command the local militia as well as his own regular troops....

The Major-Generals took over many of the functions of Lords Lieutenants, formerly agents of the Privy Council in the counties. But their social role was very different. Lords Lieutenants had been the leading aristocrats of the county. Some Major-Generals were low-born upstarts, many came from outside the county: all had troops of horse behind them to make their commands effective. This was the more galling at a time when many of the traditional county families were beginning to benefit economically from the restoration of law, order and social subordination. The rule of the Major-Generals seemed to them to jeopardize all of these. There was not much temptation to return to local government under such circumstances.

The Major-Generals interfered, on security grounds, with simple country pleasures like horse-racing, bear-baiting, and cock-fighting... The Major-Generals were instructed not only to set the poor on work - the JPs' job anyway - but to consider by what means "idle and loose people" with "no visible way of livelihood, nor calling or employment... may be compelled to work". They were to see that JPs enforced the legislation of the Long Parliament (and indeed of the Parliaments of the 1620s) against drunkenness, blasphemy and sabbath-breaking - offences which the justices were ready enough to punish in the lower orders, but in them only. The Major-Generals were to make all men responsible for the good behaviour of their servants. They were to take the initiative against any "notorious breach of the peace'. They were to interfere in the licensing of alehouses - a matter on which the House of Commons had defeated even the great Duke of Buckingham. They also interfered, often quite effectively, against corrupt oligarchies in towns. They had little confidence in juries of gentlemen and well-to-do freeholders, and Cromwell himself shared the prejudice. Above all they took control of the militia, the army of the gentry, away from the "natural rulers". Quite apart from the latter's objections to having their running of local government supervised, controlled and driven, the whole operation was very costly. At least justices of the peace and deputy-lieutenants were unpaid.

(9) Peter Laslett, The World We Have Lost (1965) page 42

During the Commonwealth, at the height of what is usually called the English Revolution, the House of Lords was abolished. It is a remarkable fact that the peers as a status group were entirely unaffected by the fundamental change in the political constitution of the country. Those that did not go into exile with the royalists, went on living in their magnificent seats, enjoying their social and apparently all their other privileges, even some of their political eminence as individuals. Cromwell's government continued to address them by their titles and ended by attempting to create its own class of peers. This is eloquent testimony to the apparently indispensable function of the English peerage in the traditional English social structure and to the extent to which their order existed independently of the House of Lords itself.

(10) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938)

Under the influence, temporarily, of General Harrison and the Fifth Monarchy men, and disgusted by the war policy of the merchants, Cromwell agreed to the calling of an Assembly of Nominees (known later as Barebone's Parliament) consisting 140 men chosen by the Independent ministers and congregations. It was a frankly party assembly, the rule of the saints, or that sober and respectable Independent middle and lower middle class which, in the country districts, had not been deeply influenced by the Levellers and remained to the end the most constant force behind the Commonwealth. The assembly soon proved too revolutionary and radical in its measures for Cromwell... After sitting five months it was dissolved in December, 1653, to make way for a new parliament for which the right wing group of officers around Lambert had prepared a brand new paper constitution - the Instrument of Government.

This constitution aimed ostensibly at securing a balance of power between Cromwell, now given the title of Lord Protector, the Council and parliament. The latter included the first time members from Scotland and Ireland and there was a redistribution of seats to give more members to the counties. Against this, the franchise was restricted to those who possessed the very high property qualification of £200 and by the disqualification of all who had taken part in the Civil Wars on the royalist side. The new parliament was thus anything but a popular or representative body, but this did not prevent it from refusing to play the part assigned to it, that of providing a constitutional cover for the group of high officers now controlling the Army. The parliament of the right proved as intractable as the parliament of the left had been and dissolved at the earliest possible moment in January 1655...

The country was divided into eleven districts, each under the control of a major-general. Strong measures were taken against the royalists, and it is from this period that much of the repressive legislation traditionally associated with Puritan rule dates. It should, however, be noted that the major-generals were often merely enforcing legislation of the preceding decade or even earlier. What the gentry most resented was forcible interference with the JPs in running local government as best pleased them.

(11) Gerald E. Aylmer, Rebellion or Revolution: England from Civil War to Restoration (1986) page 174

The full system was in operation for something over a year, from the autumn of 1655 until the mid-winter of 1656-7. It is clear, both from their surviving correspondence with the Protector and his Secretary of State and from local government records where these are available, that some of the Major-Generals were more active than others; some were tenderer towards royalists in their handling of the decimation tax, others took less part in local government as JPs and left alehouses and cruel sports to the ordinary magistrates in their counties. Hid their unpopularity was not an invention of post-Restoration royalist propaganda, as is evident from what happened in the next parliament. Most of them were outsiders to the areas where they were in charge, and a large proportion of them were self-made men below the social status and landed wealth of those who would normally have been JPs in most counties. Above all the decimation tax, whatever its intentions and whatever its justification in ex-Cavalier support for Penruddock's and other plots, looked like a return to the penal taxation of the 1640s and a breach of the 1652 Pardon and Oblivion Act.

(12) Hyman Fagan, The Commoners of England (1958) page 134

As long as he lived, the Commonwealth continued, for he was a very capable man and an able politician. During his rule the army remained loyal to him but when he died in 1658, all the disagreements came to the surface. Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth. Its Commander-in-Chief, General Monk, went over to those who were planning to restore the king.

The restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660 was the decision of all the property-owning classes-the old nobility, the new nobility, the commercial interests and the manufacturers. For these classes, the land question had been solved. Land could now be bought and sold without restriction as any other commodity. The barriers to trade and commerce had been destroyed. The English Revolution had achieved its objective of sweeping away the barriers which were preventing the rise of the new system.

The English Revolution, during its first phase, shattered the bonds of feudalism, and laid the foundation for the new system of capitalism. The restoration was not a defeat of the English Revolution; it consolidated the power of the commercial classes, Only the aims of the Levellers and Diggers had not been achieved. Although the king was restored to the throne the powers of Charles II were entirely different from those of Charles I. He ruled with limited powers, controlled by the commercial class. The Restoration showed the strength the new middle class, not its weakness, and was a sequel to the revolution. Indeed, as one writer puts it, although Charles II was called king by the Grace of God, in reality he was king by the merchants and squires.

The newly restored ruling class took revenge on the most active men of the English Revolution, as ruling classes have done throughout history. They took a gruesome revenge on Cromwell. They dug up his corpse in Westminster Abbey, dragged it through the streets, and hung it in chains on Tyburn gibbet. The condemned rebels went undaunted, to their death. On the way to the scaffold, Major-General Harrison of the New Model Army said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world."

Student Activities

John Lilburne and Parliamentary Reform (Answer Commentary)

The Diggers and Oliver Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Military Tactics in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)