Christopher Hill

Christopher Hill, the elder child and only son of Edward Harold Hill, a solicitor, and his wife, Janet Augusta Dickinson Hill, was born in York on 6th February, 1912. His parents were Methodists and he later claimed this had an important influence on his political development. He was profoundly influenced by the egalitarian message of the unorthodox Methodist preacher Theophilus Stephen Gregory and he never wavered from his central belief in human freedom and equality, now conceived in secular and this-worldly terms. (1)

At St Peter's school in York, his academic prowess was immediately evident. When Hill was 16, the two Balliol College dons - Vivien Galbraith and Kenneth Norman Bell - who marked his entrance papers agreed to award him 100%, before travelling to York to capture him for the college and prevent him going any further with his application to Cambridge University. (2)

Hill won a prestigious academic prize - the Lothian - in 1932 and a first class degree and an All Souls Fellowship in 1934. Hill became a Marxist while at Oxford University. He later admitted that this was a result of attending the Thursday Lunch Club organized by G. D. H. Cole. Hill pointed out that at these meetings "I was forced to ask questions about my own society which had previously not occurred to me." (3)

The English Revolution

In 1935 Hill joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and spent ten months in the Soviet Union. While in Moscow he became fluent in Russian and established good relations with a group of lively Soviet historians. "He was particularly interested in their work on English economic and social history, which had a major influence on his own historical thinking, while he also developed a great liking for Russia and had a love affair with a young Russian woman." (4)

On his return to the UK became an assistant lecturer at Cardiff University. In 1940 he returned to Balliol College as a tutor in modern history. By this time, he had begun to publish, at first pseudonymously, articles and reviews which, among other things, did much to draw attention to the burgeoning Soviet school of English 17th-century studies. Then, arising out of intensive debate among a group of Marxist historians, who included A. L. Morton, Robin Page Arnot and Dona Torr, he published his pamphlet, The English Revolution: 1640 (1940). Torr told a friend that it was a "pioneer work in this sphere", suggesting also that his victory was responsible for the atmosphere of greater intellectual freedom in which the historians' group flourished, "we all owe it to him in the first place and it was a victory for politics as well as theory". (5)

Christopher Hill later told a friend that the Second World War had an impact on the writing of this pamphlet. "I wrote as a very angry young man, believing he was going to be killed in a world war... it was written very fast and in a good deal of anger, and was intended to be my last will and testament." Martin Kettle has argued it was "a no-holds-barred assertion of the revolutionary nature of England between 1640 and 1660, and an assault on the traditional presentation of these years as an aberration in the stately continuity of English history." (6)

In June 1940 Hill joined joined the British Army. He served as a lieutenant in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry before becoming a major in the intelligence corps. In 1943 he was seconded to the British Foreign Office where he remained for the rest of the war. On 17th January 1944 he married Inez Waugh, the 23-year-old daughter of Gordon Bartlett, army officer, and the divorced wife of Ian Anthony Waugh. They had one daughter, Fanny. (7)

Communist Party Historians' Group

In 1946 several historians who were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, that included Christopher Hill, E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson, Dona Torr, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (8) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (9)

The group had been inspired by A. L. Morton's People's History of England (1938). Christopher Hill, the group's chairman, argued that the book provided a "broad framework" for the group's subsequent work in posing "an infinity of questions to think about"; for Eric Hobsbawm, it would become a model in how to write searching but accessible history, whereas for Raphael Samuel, who first encountered the book as a schoolboy, it was an antidote to "reactionary" history from above. According to Ben Harker: "Morton was an inspiration for a rising generation of Marxist historians who would come to dominate their respective fields." (10)

In 1947 Hill published Lenin and the Russian Revolution. Two years later Hill and Edmund Dell published the path-breaking collection of documents on the English Civil War, The Good Old Cause (1949). John Saville argued in his book, Memoirs from the Left (2003) that Hill's publication of his pamphlet, The English Revolution: 1640 (1940) was an important factor in the formation of the group: "We all regarded him as the senior member of the Historian's group, a historian of growing reputation and a man of notable integrity: characteristics which remained throughout his life." (11)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that: "The main pillars of the Group thus consisted initially of people who had graduated sufficiently early in the 1930s to have done some research, to have begun to publish and, in very exceptional cases, to have begun to teach. Among these Christopher Hill already occupied a special position as the author of a major interpretation of the English Revolution and a link with Soviet economic historians." (12)

At their first meeting on 26th October 1946, Christopher Hill suggested that the Group was divided into period subgroups, i.e. ancient, medieval, sixteenth-seventeenth centuries and the nineteenth century. The first committee was comprised of Hill as chairman and Eric Hobsbawm as treasurer. Other members of the committee included Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, John Morris and Allan Merson. Later the Communist Party Historians' Group formed a school teachers group. (13)

John Saville later recalled: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching. For me, it was a privilege I have always recognised and appreciated." (14)

The Communist Party Historians' Group expanded its work to local branches in Manchester, Nottingham and Sheffield, holding conferences, and producing a bulletin of local history in 1951. What united the Group beyond political comradeship and friendship was its members' passion for history, especially their local history, and their attempt to enrich the "battle of ideas" against conservatism. (15) According to Christos Efstathiou: Their discussions were characterised by a high level of openness and encouragement of critical perspectives, but were also products of committed intellectuals who did not separate their academic and political objectives." (16)

In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. According to Robin Briggs, Hill was the prime mover of this venture. (17) Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (18)

Khrushchev's Speech on Stalin

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. (19)

In July 1956, two members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, E. P. Thompson and John Saville, starting publishing The New Reasoner as a forum for the discussion of "questions of fundamental principle, aim, and strategy," critiquing Stalinism as well as the dogmatic politics of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It was open defiance of Party discipline to put out a publication not sanctioned by Party headquarters. As a result both Thompson and Saville were suspended from the CPGB. (20)

In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. (21)

Most members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, supported Imre Nagy and as a result, like most Marxists, left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising and a "New Left movement seemed to emerge, united under the banners of socialist humanism... the New Leftists aimed to renew this spirit by trying to organise a new democratic-leftist coalition, which in their minds would both counter the 'bipolar system' of the cold war and preserve the best cultural legacies of the British people." (22)

Christopher Hill remained for some months longer, serving as a member of the commission on inner party democracy, with which the leadership tried to appease its critics. However, he resigned after presenting a minority report that was voted down overwhelmingly at the party congress in the spring of 1957. "After this he would never engage in active politics again, although he remained instinctively a man of the left, and maintained many of the personal relationships that dated back to these years." (23)

MI5 and Christopher Hill

Although it was not revealed until 2014 MI5 had been spying on Christopher Hill since visiting the Soviet Union in 1936. Hill's file stated that he arrived at Harwich on 23rd February 1936: "John Edward Hill, a student, travelling on British Passport No 345933 which contains a recent Soviet visa. He has the appearance of a communist, but his baggage, which was searched by H. M. Customs, did not contain any subversive literature." (24)

After the war MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded Hill's telephone calls, intercepted his private correspondence and monitored his contacts. MI5 said the object of keeping checks on Hill to establish "the identity of his contacts at the University (of Oxford) and in the cultural field generally, and to obtain the names of intellectuals sympathetic to the (Communist) party who may not already be known to us". (25)

A MI5 report in 1950 revealed how Hill’s first wife, Inez, was unhappy with his political activities, which she had previously shared. "There seems to be some reason to believe that she is not only fed up with her husband’s politics but also with her husband’s political activities, especially as his political sympathies lead him, according to her, to give a considerable amount of his money to the party.... Since he is reputed to give his wife a very small sum as a dress allowance or pin money, Inez Hill may well resent the Communist Party absorbing what would otherwise go towards a new summer dress for herself." (26)

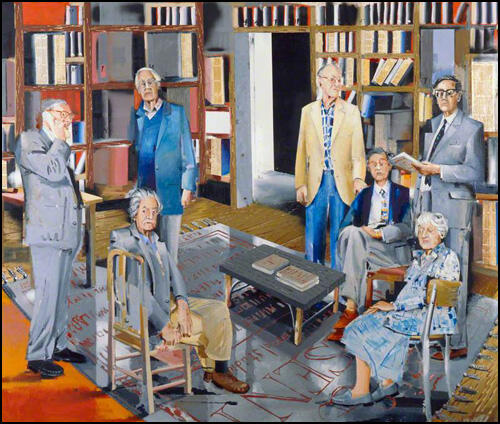

Standing: Eric Hobsbawm; Rodney Hilton; Lawrence Stone; Sir Keith Thomas;

seated: Christopher Hill; Sir John H. Elliott and Joan Thirsk (1999)

A secret MI5 memo relating the contents of a bugged conversation in the Party offices reveals how Abraham Lazarus, its south Midlands secretary, confessed to having an affair with Hill’s wife, Inez, in 1948. The memo said: "The source said that they had seen Christopher Hill and he had taken it very well. According to Hill, his wife was a "go-getter" and once she wanted a thing she went on until she got it. Hill had told Abe that his wife would ruin him. The MI5 case officer described Inez as "a somewhat neurotic, rather emotional and unstable person". The couple divorced in 1954. (27)

MI5 reported that "He is one of the leading communists at Oxford University and plays a prominent role in the Party’s cultural work. He is one of the persons whom I have selected as deserving further investigation, in order to increase our knowledge of communism at the universities." One MI5 report claimed that he had used the phrase "the crimes of Stalin" at a Communist Party of Great Britain meeting. MI5's interest in Hill declined when he left the CPGB over the Hungarian Uprising. (28)

17th Century Historian

In the 1960s and 1970s, Hill was the dominant figure in the study of seventeenth-century England. "His textbooks led the field, while he was simultaneously pouring out a stream of monographs and articles replete with learning and bursting with ideas. He succeeded in establishing in the public mind that this was the ‘century of revolution', the decisive age when England was transformed into a great economic and imperial power, amid the collapse of an old order. It is hard, in retrospect, to recognize just how far the more dramatic and disruptive aspects of the period had previously been written out of the standard account, with its preference for evolutionary change within an essentially benign picture of English constitutionalism and English social development. No historian could have overthrown this orthodoxy on his own, so clearly Hill had caught the mood of the times, and he was followed by a large group of younger scholars, including many of his own pupils. Nor could any form of doctrinaire Marxism have had such an effect, a point underlined by the fact that very few of those who admired his work had ever toyed with Marxist theory." (29)

Books by Christopher Hill included Economic Problems of the Church (1955), Puritanism and Revolution (1958), The Century of Revolution (1961), Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England (1964), Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1965), Reformation to Industrial Revolution (1967), God's Englishman (1970), The World Turned Upside Down (1972) and The Levellers and the English Revolution (1977).

After retiring as Master of Balliol he worked as a visiting professor at the Open University. He also published Intellectual Consequences of the English Revolution (1980), The World of Muggletonians (1983), The Experience of Defeat (1984), The English Bible in 17th Century England (1993), Liberty Against the Law (1996) and The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy (2002).

Christopher Hill died on 24th February, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Christopher Hill, writing in October 1971.

There are few activities more cooperative than the writing of history. The author puts his name brashly on the title-page and the reviewers rightly attack him for his errors and misinterpretations; but none knows better than he how much his whole enterprise depends on the preceding labours of others.

(2) Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down (1972)

There were, we may oversimplify, two revolutions in mid-seventeenth-century England. The one which succeeded established the sacred rights of property (abolition of feudal tenures, no arbitrary taxation), gave political power to the propertied (sovereignty of Parliament and common law, abolition of prerogative courts), and removed all impediments to the triumph of the ideology of the men of property - the protestant ethic. There was, however, another revolution which never happened, though from time to time it threatened. This might have established communal property, a far wider democracy in political and legal institutions, might have disestablished the state church and rejected the Protestant ethic.

The object of the present book is to look at this revolt within the Revolution and the fascinating flood of radical ideas which it threw up. History has to be rewritten in every generation, because although the past does not change the present does; each generation asks new questions of the past, and finds new areas of sympathy as it re-lives different aspects of the experiences of its predecessors. The Levellers were better understood as political democracy established itself in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century England; the Diggers have something to say to twentieth-century socialists. Now that the Protestant ethic itself, the greatest achievement of European bourgeois society in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is at last being questioned after a rule of three or four centuries, we can study with a new sympathy the Diggers, the Ranters, and the many other daring thinkers who in the seventeenth century refused to bow down and worship it.

(3) Brian Manning, Socialist Review (March, 2003)

The undoubted dominance of Christopher Hill in the history of the English Revolution may be attributed to his prolific record of books and articles, and his continuous engagement in debate with other historians; to the breadth of his learning, embracing the history of literature, the law, science, as well as religion and economics; to the fact that his work set the agenda and the standard to which all historians of the period had to address themselves, whether in support of or opposition to his methods and interpretations; but above all to the inspiration he drew from Marxism. The English Revolution took place in a culture dominated by religious ideas and religious language, and Christopher Hill recognised that he had to uncover the social context of religion in order to find the key to understanding the English Revolution, and as a Marxist to ascertain the interrelationships between the intellectual and social aspects of the period.

Christopher Hill spent his life seeking to persuade people that the English Revolution was a decisive event or, as he titled his last book, England's Turning Point (1998), and he succeeded.

A brilliant, often sardonic wit, an incisive mind, and a deeply compassionate person, he was the finest product of the British radical tradition, and he did more than anybody to establish Marxism as central to that tradition. It is hard to accept that there will no longer, year by year, be a new book by Christopher Hill, enlightening, stimulating new thoughts, and no doubt something to quarrel with.

(4) Martin Kettle, The Guardian (26th February, 2003)

Christopher Hill, who has died aged 91, was the commanding interpreter of 17th-century England, and of much else besides. As a public figure, he achieved his greatest fame as master of Balliol College, Oxford, a post he held from 1965 until 1978. Yet it was as the defining Marxist historian of the century of revolution, the title of one of the most widely studied of his many books, that he became known to generations of students around the world. For all these, too, he will always be the master.

It would be a pardonable exaggeration to say that Hill created the way in which the people of late 20th-century Britain - and the left in particular - looked at the history of 17th-century England. As he never tired of pointing out, some of the themes he illuminated so richly had already been explored by left-wing scholars in the 1930s. But from 1940, when he published his tercentenary essay, The English Revolution 1640, his own voluminously expanding and unfailingly literate work became the starting point of most subsequent interpretation, even for those who rejected his method and conclusions.

No historian of recent times was so synonymous with his period of study; he is the reason why most of us know anything about the 17th century at all. He was, EP Thompson once said, the dean and paragon of English historians.

Hill was born in York, where his father was a solicitor. His parents were Methodists, a fact to which he attributed his lifelong political and intellectual apostasy. Though his life was to be the embodiment of a secularised form of dissent, his high moral seriousness and egalitarianism surely had roots in this radical Protestant background.

At St Peter's school in York, his academic prowess was immediately evident. It is said that, when Hill was 16, the two Balliol dons - Vivien Galbraith and Kenneth Bell - who marked his entrance papers agreed to award him 100%, before travelling to York to capture him for the college and prevent him going any further with a Cambridge application. Galbraith, in particular, was to remain an immense influence.

Hill's association with Balliol was to continue, with only brief interruptions, from his arrival as an undergraduate in 1931 until his retirement as master 47 years later. Academic honours regularly fell his way, starting with the prestigious Lothian prize in 1932, and continuing with a first-class degree in 1934 and an All Souls fellowship that winter. But he was a successful rugby player too, the scorer of a famous cup-winning try for Balliol. Even more lastingly, he had become a Marxist.

Exactly when and why this happened is uncertain, since Hill was always notoriously inscrutable about discussing his personal life. He once claimed it came about through trying to make sense of the 17th-century metaphysical poets, but although he read Marx as an undergraduate, the moment of his conversion to communism is elusive.

His contemporary, RW Southern, once teasingly remembered "a time when Christopher was not in the least bit leftish", but Hill was an undergraduate during the period of the great depression, the hunger marches, the New Deal, Hitler's rise (he visited the Weimar Republic before going up to Oxford), and the first (favourable) impact of Stalin in the west. He was a regular attender at GDH Cole's Thursday Lunch Club, where, as he once put it, "I was forced to ask questions about my own society which had previously not occurred to me."

Certainly by the time he graduated, Hill had joined the Communist party. In 1935, he spent a year in the Soviet Union, during which he was very ill, but also formed a lasting affection for Russian life - and a somewhat less lasting one for Soviet politics.

After Moscow, he had two years as an assistant lecturer at University College, Cardiff, before returning to Balliol as a fellow and tutor in modern history. In 1940, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, before becoming a major in the intelligence corps and being seconded to the Foreign Office from 1943 until the end of the war. This was, to put it mildly, an intriguing period, about which he rarely let fall much detail.

By this time, he had begun to publish, at first pseudonymously, articles and reviews which, among other things, did much to draw attention to the burgeoning Soviet school of English 17th-century studies. Then, in 1940, arising out of intensive debate among a group of Marxist historians, who included Leslie Morton, Robin Page Arnot and - particularly influential on Hill - Dona Torr, came the decisive The English Revolution 1640.

The essay was originally published as one of a collection of three reflections (the others were by Margaret James and Edgell Rickword). Hill's contribution, which was subsequently published alone, was a no-holds-barred assertion of the revolutionary nature of England between 1640 and 1660, and an assault on the traditional presentation of these years as an aberration in the stately continuity of English history.

"I wrote as a very angry young man, believing he was going to be killed in a world war," Hill later told an interviewer. The book, he said, "was written very fast and in a good deal of anger, [and] was intended to be my last will and testament." It has rarely, if ever, been out of print since.

The discussions surround- ing Hill's essay also produced, in 1946, the Communist Party Historians Group, an association he regarded as "the greatest single influence" on his subsequent work. This formidable academy, which inclu- ded Edmund Dell, Maurice Dobb, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawm, James Jeffreys, Victor Kiernan, George Rudé, Raphael Samuel, John Saville and Dorothy Thompson, has a good claim to have redefined the study of history in Britain, especially after the launch, in 1952, of the journal Past And Present, of which Hill rapidly became the moving spirit and, later, the doyen. It also generated the path-breaking collection of documents, The Good Old Cause, that he edited with Dell in 1949.

The active, 20-year involvement with communism, which also led to his short biography, Lenin And The Russian Revolution (1947), came to a crisis after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. Along with many in the CP, Hill had become disenchanted with the party's lack of democracy and its reluctance to criticise the Soviet Union. Both issues came to a head in the late weeks of 1956, though his own break did not come until the following year. He was appointed to a CP review of inner-party democracy, but the rejection of the critical minority report, written by Hill (with Peter Cadogan and Malcolm MacEwen), precipitated his final departure.

These were watershed years in Hill's personal life too. A wartime marriage to Inez Waugh, the former wife of a colleague, produced a home life which combined the high seriousness of Balliol Marxism with an extravagant bohemianism. It also produced their daughter Fanny Hill, later a dashing figure on the Oxford scene, who drowned off the Spanish coast in her 40s. The marriage collapsed early and, in 1956, he married again, this time to Bridget Sutton, then a history tutor with the Workers' Educational Association in Staffordshire. Turbulence was replaced by the single greatest happiness of Hill's life. With Bridget (obituary, August 13 2002), he had a son and two daughters, one of whom died in a car accident.

After 1957, Hill's career ascended to new heights as he began the remarkable output of books on which his reputation will rest, and which continued undiminished until he was well into his 80s. Hill always argued that the connection between leaving the CP and his wider fame was post-hoc rather than propter-hoc, and it is certainly true that 1956-57 caused no revolution (let alone a counter-revolution) in his analysis of the English revolution. On the other hand, the Bridget effect can hardly be underestimated.

If the steady flow of books which began with Economic Problems Of The Church (1955) can, to some extent, be seen as a succession of more scholarly explorations of the themes sketched out in the early didactic essays, they also reflect the extraordinary sweep of Hill's interests and mind. Central to the whole project was a patient fascination with religion, represented, in particular, in his attempt to understand the revolutionary power of puritanism.

But Hill's explorations were in no way bound by traditional or preconceived theories. The single, most striking and controversial aspect of his method was the way in which he subtly identified intellectual connections, currents and continuities between the most unlikely pieces of evidence - from scraps of court records to Paradise Lost and Pilgrim's Progress. His use of literary sources was one of his most fascinating characteristics.

Many of the tasks he set himself were laid out in his next book, Puritanism And Revolution (1958). They were further explored in Society And Puritanism In Pre-Revolutionary England (1964) and the remarkable Intellectual Origins Of The English Revolution (1965, and extensively revised 31 years later), this last based on his 1962 Ford lectures. Alongside came more popular works of exegesis - a Historical Association pamphlet on Cromwell (1958), the bestselling (but not adulatory) biography God's Englishman (1970), the textbook The Century Of Revolution (1961) and the hugely successful Penguin economic history, Reformation To Industrial Revolution (1967).

Those who heard Hill deliver the lectures on which it is based - lectures delivered in a nervous, slightly stuttering voice - will always reserve a special place for his 1972 study of radical and millenarian ideas, The World Turned Upside Down. Not only was this one of the very few history books to be turned into a play (at the National theatre), it was also a work made more exciting by the time in which it was written, an era of counter-cultural energy which Hill observed (and quietly celebrated) from the Balliol master's lodgings.

This was a period of immense academic daring (and, thought some, of over-reaching) as Hill scythed through received tradition in his study of AntiChrist In 17th-century England (1971) and his controversial study of Milton And The English Revolution (1977), which, like many of his later works, was written at the plain but lovely house in Périgord which Bridget badgered him into buying in 1969.

Meanwhile, in 1965, Hill had defeated Ronald Bell in the election for master of Balliol, a success which caused raised eyebrows (it was only 10 years or so since academics with Hill's politics had been, to all intents and purposes, blacklisted from many posts) and much press attention. His tenure was deft and collegiate, and he tried to maintain his teaching and research amid the administrative and ceremonial duties. He never seriously hid his enthusiasm for the two main innovations of his mastership - the opening of male-only Balliol to women, and the representation of students on the college governing body. "Common sense varies among the young," he admitted, "as among the old."

Retirement found his productivity undiminished. He moved to Sibford Ferris, on the Cotswold hills, and, for two years, worked as a visiting professor at the Open University, an entirely characteristic effort to bring his learning to a wider audience. Then he settled down to further books: Some Intellectual Consequences Of The English Revolution (1980); The World Of The Muggletonians (1983); and The Experience Of Defeat (1984), an account of the Restoration made poignant by the reverses 20th-century leftwing politics were suffering at the time.

A marvellously vivid study of Bunyan followed in 1988, before The English Bible In 17th-century England (1993) and Liberty Against The Law (1996). Three volumes of essays were published in the 1980s - throughout his life, Hill wrote some of his most challenging and original work in articles and reviews.

Hill was honoured by an OUP festschrift, Puritans And Revolutionaries, when he retired from Balliol in 1978, and Verso published a series of tributes and criticisms, Reviving The English Revolution, 10 years later. Yet, for the last 20 years of his life, he became once again a more controversial figure.

His methodology was famously assaulted by JH Hexter in a Times Literary Supplement review in 1975, and his assessment of Milton was powerfully denounced by Blair Worden. A reaction against his big reading of 17th-century history took root in the work of Conrad Russell, John Morrill and others. Yet Morrill's tribute in 1989 - "If we can be sure that the 17th century changed England and Englishmen more than any other century bar the present one, we owe that recognition to him more than to any other scholar" - shows how, even in relative eclipse, Hill remained the central point of reference in 17th-century studies.

People always felt there was something enigmatic about Hill. Whether as a friend walking through Oxfordshire or the Dordogne, as a tutor hunched in his armchair discussing an essay - and still more on formal occasions - he kept his cards close to his chest, forcing you to do the talking, making you listen to what you were saying in the way that he was listening too. But then he would make a joke, often just a pointed ironic observation, that made you love him. As someone once said, although he affected to be severe, he could not help being benign.

But tough too. Always. Hill once gave a radio talk marking the centenary of the publication of Das Kapital. He ended it by telling how, in old age, Marx had bumped into a fellow revolutionary from the 1848 barricades, now prosperous and complacent. The acquaintance reflected that, as one got older, one became less radical and less political. "Do you?" Marx replied. "Do you? Well, I do not!" And nor, he clearly intended us to understand, did Christopher Hill.

(5) Graham Stevenson, Christopher Hill (19th September, 2008)

Born John Edward Christopher Hill on February 6th 1912 in York, where his father was a solicitor, his parents were Methodists, a fact of significance to his life-long area of study. When he was 16 and at St Peter’s school in York, the two Balliol dons who marked his entrance papers, Vivien Galbraith and Kenneth Bell, awarded him 100% and personally travelled to York to secure him for Oxford, rather than Cambridge.

He was then associated with Balliol from his time as an undergraduate in 1931 to his retirement as master 47 years later. He won a prestigious academic prize – the Lothian – in 1932 and a first class degree and an All Souls Fellowship in 1934.

Seemingly, the circumstances of his adherence to Marxism are unknown and Hill never shed light on any aspects of his personal life. He was of course an undergraduate during the Depression and the rise of Nazism. Hill attended GDH Cole’s Thursday lunch club regularly and found the experience tested his own previously held conceptions. He was certainly a member of the Communist Party by the time he had graduated and he spent ten months of 1935 in the Soviet Union, being ill for some of the time he was there. For the following two years he was an assistant lecturer at University College Cardiff, before returning to Balliol as a fellow and tutor in modern history.Hill gave a talk on radio marking the centenary of the publication of Marx’s “Das Kapital”. He ended it by recounting how Marx had accidentally come across some former comrades from the 1848 revolutions, may years later. They had become prosperous and one, reflecting on old times, indicated how he felt that he was becoming less radical as he aged. “Do you?” said Marx, “Well I do not.” Many thought that Hill had quoted this to reflect upon himself.

Whatever the case, unarguably, the 1970s saw Hill become increasingly more and not less radical in his interpretations, as his confidence in his subject became masterful. There was “Anti-Christ in 17th Century England” and “Milton and the English Revolution”, which particularly provoked controversy. Indeed, his work became the target of attack by a range of critics.

For a couple of years after he retired he was a visiting professor at the Open University. But the titles continued to pour out of the lifetime of study he had given to his period. There was “Some Intellectual Consequences of the English Revolution” (1980), “The World of the Muggletonians” (1983), “The Experience of Defeat” (1984), an account of the Restoration period, a study of Bunyan in 1988, then “The English Bible in 17th Century England” in 1993 and “Liberty against the Law” (1996). Three volumes of essays also appeared in the 1980s, reflecting the abundance of articles and reviews he had written throughout.

Both the OUP and Verso published tribute collections, in the form of “Puritans and Revolutionaries” and “Reviving the English Revolution”. When he died, on February 24th 2003 aged 91, it was as the historian of the 17th century in England. Hill may not have forced a general acceptance of the Marxist interpretation of the Civil War but he certainly won by the body of his work an acceptance of the particular importance of that century to the rest of British history.

(6) Richard Norton-Taylor, The Guardian (24th October 2014)

MI5 amassed hundreds of records on Eric Hobsbawm and Christopher Hill, two of Britain’s leading historians who were both once members of the Communist party, secret files have revealed.

The scholars were subjected to persistent surveillance for decades as MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded their telephone calls, intercepted their private correspondence and monitored their contacts, the files show. Some of the surveillance gave MI5 more details about their targets’ personal lives than any threat to national security.

The files, released at the National Archives on Friday, reveal the extent to which MI5, including its most senior officers, secretly kept tabs on the personal and professional activities of communists and suspected communists, a task it began before the cold war. The papers also show that MI5 opened personal files on the popular Oxford historian AJP Taylor, the writer Iris Murdoch, and the moral philosopher Mary Warnock after they and Hill signed a letter supporting a march against the nuclear bomb in 1959.

At a fraught meeting at the party’s headquarters at King Street in London’s Covent Garden, at the end of 1956, Hobsbawm, Hill and the writer Doris Lessing agreed to write a letter attacking the party leadership’s “uncritical support… to Soviet action in Hungary”, a reference to the crushing of the uprising there. That support, the letter explained, was “the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of facts”. Hill, who left the party a year later, used the phrase "the crimes of Stalin" at the meeting, according to the MI5 report. The party’s paper, the Daily Worker, refused to publish the letter which was later run by Tribune, the leftwing weekly.

Lady Warnock told the Guardian on Thursday night: “I’d love to see the file, or anybody’s file come to that, to see what was/is regarded as suspicious … I am completely taken aback and even faintly flattered.”

Hobsbawm, who was refused access to his files when he asked to see them five years ago, died in 2012, and Hill died in 2003. Many passages, sometimes whole pages, of their files remain redacted and an entire file on Hobsbawm has been “temporarily retained”. The files include long lists of names and addresses of letters written by Hobsbawm and Hill.

They make clear that MI5 frequently read – or was sent – copies of as many as 10 letters a day. At the same time, its officers, or special branch officers, or their informants – one of whom was given the codename Ratcatcher – were secretly taking notes of their phone calls and meetings.

The files show that Hobsbawm, who became one of Britain’s most respected historians and was made a Companion of Honour while Tony Blair was prime minister, first came to the notice of MI5 in 1942 when he and 38 colleagues were described as being “obvious members of the CPGB [the Communist party of Great Britain] on Merseyside”. He became number 211,764 on MI5’s index of personal files. Although he was cleared of “suspicion of engaging in subversive activities or propaganda in the army”, MI5 noted it was doubtful that he would be suitable for the Intelligence Corps. Roger Hollis, later head of MI5, and Valentine Vivian, the deputy chief of MI6, prevented him from joining the Foreign Office’s political intelligence department.

At the end of the war, in July 1945, an MI5 officer noted: “As he is known to be in contact with communists I should be interested to see all his personal correspondence”.

MI5 said the object of keeping checks on Hobsbawm was “to establish the identities of his contacts and to unearth overt or covert intellectual Communists who may be unknown to us”. Similarly, Hill was kept under surveillance, the files note, to establish “the identity of his contacts at the University [of Oxford] and in the cultural field generally, and to obtain the names of intellectuals sympathetic to the [Communist] party who may not already be known to us”.

Telephone intercepts disclosed that Hobsbawm and his family were friendly with Alan Nunn May – a British physicist who had confessed to spying for Russia and was released from jail in 1952 – and on one occasion put him up for the night. There is no evidence in the files of any attempt by either Hobsbawm or Hill to spy for Moscow or that the Russians were interested in them for any such purpose.

One early file on Hobsbawm describes his uncle Harry, with whom he sometimes stayed, as “sneering, half Jew in appearance, having a long nose”.

The surveillance intruded into the targets’ relationships. Hobsbawm is recorded in 1952 as having “difficulties with his [first] wife, who,” an MI5 officer noted, “does not consider him to be a fervent enough Communist”.

A report in 1950 revealed how Hill’s first wife, Inez, was becoming “sick to death” of his Communist party affiliation, which she had previously shared. “There seems to be some reason to believe that she is not only fed up with her husband’s politics but also with her husband’s political activities, especially as his political sympathies lead him, according to her, to give a considerable amount of his money to the party,” the report stated. A subsequent report revealed she was having an affair with another Communist party official.

Hobsbawm never left the Communist party but the MI5 files show he argued with the party leadership so strongly that it considered dismissing him, according to transcripts of MI5’s bugged conversations.

Earlier that year, MI6 asked MI5 if they had any objection to telling the CIA that Hobsbawm was going on a tour of South America funded, to its surprise, by the Rockefeller Foundation (Hobsbawm had already visited Cuba). In a document marked Top Secret, dated 13 May 1963, MI5 told MI6: “A reliable and very delicate source has reported that Hobsbawm visited a number of countries.”

The files also reveal that the FBI feared that the atom bomb pioneer Robert Oppenheimer would use a visit to Britain to defect to Russia. He had come under investigation in America for his leftwing sympathies and in 1954 the FBI urged MI5 to put him under surveillance if he entered the UK. In a cable from the US embassy, legal attache JA Cimperman wrote: “Information has been received that Oppenheimer may defect from France in September 1954. According to the source, Oppenheimer will first come to England and then go to France, where he will vanish into Soviet hands. No further details are available.”

MI5 was anxious to assist. One officer noted: “Undoubtedly, if Oppenheimer came here under the shadow of reliable reports that he was possibly going to defect to the Russians, we should treat the matter as of major importance and in that light do what we could to help.” The warning proved to be a false alarm and no such attempt occurred.

Hill, who became a celebrated historian of the English civil war and was later elected Master of Balliol College, Oxford, first came to MI5’s notice when he visited Russia as an undergraduate in 1935. On his return a year later, MI5 noted that Hill “has the appearance of a Communist; but his baggage which was searched by HM Customs, did not contain any subversive literature”.

“My BBC contact tells me that Hobsbawm is still an occasional contributor to the Third Programme … Some recent talks were entitled ‘Sicilian Peasant Risings’ and ‘Robin Hood’.” What is described as “slightly unexpected” was a series of talks on “Jazz”.

The files show he was turned down after applying for a post in military intelligence. He "should not be employed as a lecturer to the Forces", MI5 insisted in 1946.

In 1953, MI5 described Hill as a “popular history don at Balliol … a Marxist and Communist party member”. It added, apparently with relief: “He does not, however, engage in Soviet studies. His period is the seventeenth century.”

One file contains a copy of a letter to Tribune supporting an anti-nuclear bomb march organised for 27 November 1959. It was signed by Murdoch, Taylor and Warnock, as well as Hill. MI5 had opened personal files on all of them.

Three years later, in October 1961, MI5 noted that Hill had become “a strong supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament”. It added: “This fact, however, does not shed any light on his political sympathies, since very many shades of left wing opinion are opposed to nuclear weapons.”

Lord Lipsey, who had been asked by Hobsbawm to inquire about the possibility of MI5 keeping files on him, said on Thursday: “As a supporter of increased openness I am at least delighted that these files have finally been released.”

(7) Cahal Milmo, The Independent (24th October 2014)

Between them the Oxbridge historians Christopher Hill and Eric Hobsbawn helped recast the teaching of the past in British universities and beyond. But their academic eminence did little to protect them from the Cold War scrutiny of MI5, it has been revealed.

Secret files released today tell the story of how two of Britain’s leading historians were placed under rigorous surveillance by the Security Service after its senior officers became concerned about the influence of communist academics in the country’s top universities.

While the energies of MI5 may have been better deployed winkling out a different set of university-inspired communists in the shape of the Cambridge Five spy ring of Kim Philby and others, scrutiny instead focused on the two openly Marxist scholars amid fears that they were helping Moscow to gain a grip on British academia.

But rather than uncovering evidence of sedition, the documents released today at the National Archives in Kew, west London, show that MI5 had to console itself with tales of marital infidelity, music recitals and turgid doctrinal disputes with the British Communist Party.

By means of phone intercepts, bugged offices, steamed-open mail and informants, the security service painstakingly built up a picture of the personal and political lives of the two historians, ranging from Hobsbawm’s interest in jazz to Hill’s reluctance to give his wife a clothing allowance.

Hobsbawm’s three-volume economic history of the rise of capitalism, which for the first time told the events of the past through the prism of the underclass rather than great men, propelled him to eminence among 20th century British historians. Hill, who was master of Oxford’s Balliol College for 13 years, was considered a world authority on the English Revolution of the 17th century.

But both men’s early embrace of communism as students in the 1930s - ironically around the same time as Philby and the other members of the Cambridge Five were recruited by Moscow - marked them out in the early days of the Cold War as of interest to MI5 amid paranoia about the extent of Soviet entryism.

As the officer who ordered extensive surveillance of Hill, including the tapping of his phone line, put it in 1951: “He is one of the leading communists at Oxford University and plays a prominent role in the Party’s cultural work. He is one of the persons whom I have selected as deserving further investigation, in order to increase our knowledge of communism at the universities.”

But while MI5 fretted about Hill’s openly-declared Marxist and pro-Russian leanings (reinforced during a 10-month trip to Russia in 1936), the only evidence of betrayal it obtained on the lecturer, who had worked for British military intelligence during the war, was that inflicted upon him by his wife.

A secret MI5 memo relating the contents of a bugged conversation in the Party offices reveals how Abraham Lazarus, its south Midlands secretary, confessed to having an affair with Hill’s wife, Inez, in 1948.

The memo said: “The [source] said that they had seen Christopher Hill and he had taken it very well. According to Hill, his wife was a ‘go-getter’ and once she wanted a thing she went on until she got it. Hill had told Abe that his wife would ruin him. Apparently she had already done so financially, because he had come up to town on a lorry.”

The MI5 case officers painted an unflattering picture of the Hills, describing Inez as “a somewhat neurotic, rather emotional and unstable person”, and her historian husband as more interested in funding the Party than her wardrobe.

Another acid memo written in 1950 said: “Since he is reputed to give his wife a very small sum as a dress allowance or pin money, Inez Hill may well resent the Communist Party absorbing what would otherwise go towards a new summer dress for herself.”

It added: “Another source has often suggested that Inez Hill is not only fed up with her husband’s politics, but also with her husband… Christopher Hill himself has been described in the past as somewhat mean-minded, pompous and tiresome.”

Though brutal in its assessment of Hill’s character, MI5 was proved right about the state of his marriage - by 1954 the couple had divorced.

The Security Service’s scrutiny of Hobsbawm, who first came to MI5’s attention when he invited a German communist to lecture troops while he was serving in the Army Education Corps in 1942, revealed little of comparable excitement other than a long tussle between him and fellow Marxist academics.

Despite revealing links with senior Communist Party members and the convicted Soviet nuclear spy Alan Nunn May, the MI5 bugging could find no evidence of anything untoward in Hobsbawm’s activities as head of its historian’s group.

Indeed, the harshest words for the academic came from within the ranks of the Party itself after he was found to have written an article under a pseudonym for a non-communist publication. One party official described him as a “dangerous character” while another labelled him “a very slippery customer”.

For his own part, Hobsbawm expressed frustration with his contribution to the Party cause. An “autobiography” obtained by MI5 in 1952 read: “I don’t feel I’ve done what I might for the Party… My sort of professional work is probably the best I can do but I’d quite like to have more to do with factory workers.”

Like many sympathisers, the two historians drifted away from the communist cause in the wake of Moscow’s brutal suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. Hill left in 1957 while Hobsbawm became avowedly anti-Soviet.

In the meantime, MI5 continued its in-depth surveillance of British academia for any signs of subversion. After Hill had addressed the members of the Reading Communist Party, a police report to the security service noted evidence of the Marxists’ other attempts to gain influence. It recommended scrutiny of the event in question - a “gramophone recital of classical music”.

(8) Christopher Andrew, Security Service File Release (October 2014)

For many historians, the highlight of the latest MI5 declassification at the National Archives will be the multi-volume files on two of the world’s leading Communist historians, both British: Christopher Hill and Eric Hobsbawm. Christopher Hill’s file, which begins at KV2/3941, shows that he first came to MI5’s attention when he visited Russia in 1935 while an undergraduate at Oxford University. He returned to Russia in 1936 and joined the Communist Party.

After WW2 MI5 considered Hill, then a Fellow (and later Master) of Balliol College as Q "one of the leading Communists at Oxford University". In 1951 it applied successfully for a Home Office Warrant (HOW) to intercept Hill’s correspondence and telephone calls in the belief that this would increase MI5’s ‘knowledge of Communism and the Universities’ in general as well as of Hill’s own activities. The product of the HOW adds to our understanding of, for example, Hill’s decision to leave the Party in 1957 in protest against the leadership’s attempt to suppress criticism of the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Rising in 1956. The Party leader, John Gollan, was overhead saying that Q "out of those who had left, he would not have done much to dissuade any of them, except Christopher Hill". Hill wrote to Communist Party HQ in an intercepted letter which is on his file: "We have been living for too long in a world of illusions. It was a smug, cosy little world."

(9) Mike Laycock, The York Press (4th November 2014)

Christopher Hill was born in Bishopthorpe Road in February 1912 to a family of devout Methodists, with his father working as a solicitor, and he attended St Peter's School.

He went on to become one of Britain's leading historians - a celebrated historian of the English civil war - but, along with another historian, Eric Hobsbawm, he also became a member of the Communist party.

It has now emerged that the scholars were subjected to persistent surveillance for decades as MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded their telephone calls, intercepted their private correspondence and monitored their contacts.

The files, which have been released from the National Archives, show that some of the surveillance gave MI5 more details about their personal lives than any threat to national security.

A report in 1950 revealed how Hill’s first wife, Inez, was becoming “sick to death” of his Communist party affiliation, which she had previously shared.

“There seems to be some reason to believe that she is not only fed up with her husband’s politics but also with her husband’s political activities, especially as his political sympathies lead him, according to her, to give a considerable amount of his money to the party,” the report stated.

A subsequent report revealed she was having an affair with another Communist party official.

Hill left the Communist party in 1957, a year after he and Hobsbawm had written a letter attacking the party leadership’s “uncritical support " to the Soviet crushing of the uprising in Hungary.

He had first come to MI5’s notice when he visited Russia as an undergraduate in 1935. On his return a year later, MI5 noted that Hill “has the appearance of a Communist; but his baggage which was searched by HM Customs, did not contain any subversive literature”.

In 1953, MI5 described him as a "popular history don at Balliol … a Marxist and Communist party member" but noted he did not engage in Soviet studies.

In 1961, it noted Hill had become “a strong supporter" of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament but said this did not shed any light on his political sympathies.