Past and Present

In 1946 several historians who were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, that included Christopher Hill, E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson, Dona Torr, Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan, Maurice Dobb, James B. Jefferys, John Morris and Allan Merson, formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (1) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (2)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that: "The main pillars of the Group thus consisted initially of people who had graduated sufficiently early in the 1930s to have done some research, to have begun to publish and, in very exceptional cases, to have begun to teach. Among these Christopher Hill already occupied a special position as the author of a major interpretation of the English Revolution and a link with Soviet economic historians." (3)

John Saville later recalled: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching. For me, it was a privilege I have always recognised and appreciated." (4)

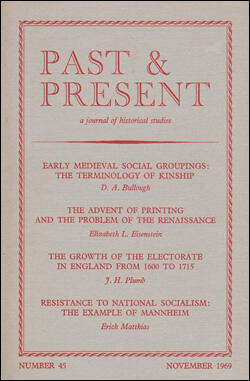

In January 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. According to his biographer, Christopher Hill was the prime mover of this venture. (5) Hobsbawm was appointed assistant editor. The editor was John Morris and members of the editorial board included:Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. H. M. Jones, Geoffrey Barraclough, Reginald Betts, Maurice Dobb, Vere G. Childe, and David B. Quinn. Its aim was to break the mould of traditional historical journals by introducing new ideas and approaches, not least those of the social sciences. In its opening number, it said: "We shall make a consistent attempt to widen the somewhat narrow horizon of traditional historical studies among the English-speaking public. The serious student in the mid-twentieth-century can no longer rest in ignorance of the history and historical thought of the greater part of the world." (6) (11a)

Hobsbawm later explained: "When some communist historians founded a new historical journal, Past and Present, in 1952, about as bad a time in the Cold War as can be imagined, we deliberately planned it not as a Marxist journal, but as a common platform for a "popular front" of historians, to be judged not by the badge in the author's ideological buttonhole, but by the contents of their articles. We desperately wanted to broaden the base of the editorial board, which at the start was naturally dominated by Party members, since only the rare, usually indigenous, radical historian with a safe academic base, such as A. H. M. Jones, the ancient historian from Cambridge, had the courage to sit at the same table as the Bolsheviks." (7)

Eventually the editors of the journal managed to persuade a group of non-Marxist historians of subsequent eminence, led by Lawrence Stone, and John Elliott, later Regius Professor at Oxford, who had sympathized with their objectives offered to join the board collectively on condition that they dropped the ideologically suspect phrase "a journal of scientific history" from its masthead. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (8)

Primary Sources

(1) Emma Griffin, History Today (2nd February 2015)

The cause of this fledgling historical strand was greatly advanced through association with some of the leading scholars of the age, including the Communist Party History Group members Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, Raphael Samuel and E. P. Thompson. These four were also part of the group that founded the journal Past & Present, now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today. Thompson’s monumental The Making of the English Working Class (1963) was arguably the single most significant contribution to working-class history, but it is easy to forget that he was just one part of a larger community of scholars with a shared interest in the emergence and experiences of the working class at the time of the British Industrial Revolution.

(7) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

When some communist historians founded a new historical journal, Past and Present, in 1952, about as bad a time in the Cold War as can be imagined, we deliberately planned it not as a Marxist journal, but as a common platform for a "popular front" of historians, to be judged not by the badge in the author's ideological buttonhole, but by the contents of their articles. We desperately wanted to broaden the base of the editorial board, which at the start was naturally dominated by Party members, since only the rare, usually indigenous, radical historian with a safe academic base, such as A. H. M. Jones, the ancient historian from Cambridge, had the courage to sit at the same table as the Bolsheviks…

We were equally keen to extend the range of our contributors. For several years we failed in the first task, although, thanks to our excellent reputation amo0ng younger academics, we soon did better on the second. In 1958 we succeeded. A group of non-Marxist historians of subsequent eminence, led by Lawrence Stone, shortly about to go to Princeton, and the present Sir John Elliott, later Regius Professor at Oxford, who had sympathized with our objectives but until then had found it impossible formally to join the former red establishment, offered to join us collectively on condition that we dropped the ideologically suspect phrase "a journal of scientific history" from our masthead. It was a cheap price to pay. They did not ask us about our political opinions – actually orthodox communists were no longer easy to find on the board – we did not enquire into theirs, and no ideological problems have ever arisen on its board since then. Even the Institute of Historical Research, which had steadfastly refused to include the journal in its library, relented.