Hungarian Uprising

The Hungarian Communist Party was very small during the Second World War. Led by Laszlo Rajk, party members were involved in fighting a largely unsuccessful underground war against Adolf Hitler.

The Soviet Army invaded Hungary in September 1944. It set up an alternative government in Debrecen on 21st December 1944 but did not capture Budapest until 18th January 1945. Soon afterwards Zolton Tildy became the provisional prime minister.

In elections held in November, 1945, the Smallholders Party won 57% of the vote. The Hungarian Workers Party, now under the leadership of Matyas Rakosi and Erno Gero, received support from only 17% of the population. The Soviet commander in Hungary, Marshal Voroshilov, refused to allow the Smallholders Party to form a government. Instead Voroshilov established a coalition government with the communists holding some of the key posts. Zoltan Tildy, was named president and Frenc Nagy prime minister. Matyas Rakosi became deputy prime minister.

Laszlo Rajk became minister of the interior and in this post established the security police. In February 1947 the police began arresting leaders of the Smallholders Party and the National Peasant Party. Several prominent figures in both parties escaped abroad. Later Matyas Rakosi boasted that he had dealt with his partners in the government, one by one, "cutting them off like slices of salami."

The Hungarian Communist Party became the largest single party in the elections in 1947 and served in the coalition People's Independence Front government. The communists gradually gained control of the government and by 1948 the Social Democratic Party ceased to exist as an independent organization. Its leader, Bela Kovacs was arrested and sent to Siberia. Other opposition leaders such as Anna Kethly, Frenc Nagy and Istvan Szabo were imprisoned or sent into exile.

Matyas Rakosi also demanded complete obedience from fellow members of the Hungarian Communist Party. His main rival for power was Laszlo Rajk, who was now foreign secretary. Rajk was arrested and at his trial in September 1949 he confessed to being an agent of Miklos Horthy, Leon Trotsky, Josip Tito and Western imperialism and admitted that he had taken part in a murder plot against Matyas Rakosi and Erno Gero. Laszlo Radk was found guilty and executed. Janos Kadar and other dissidents were also purged from the party during this period.

Matyas Rakosi now attempted to impose authoritarian rule on Hungary. An estimated 2,000 people were executed and over 100,000 were imprisoned. These policies were opposed by some members of the Hungarian Workers Party and around 200,000 were expelled by Rakosi from the organization.

Rakosi rapidly expanded the education system in Hungary. This was an attempt to replace the educated class of the past by what Rakosi called a new "toiling intelligentsia". Communist indoctrination took place in schools and universities. Religious instruction was denounced as propaganda and was gradually eliminated from schools.

Cardinal Joseph Mindszenty, who had bravely opposed the German Nazis and the Hungarian Fascists during the Second World War, was arrested in December, 1948, and accused of treason. After five weeks of torture he confessed to the charges made against him and he was condemned to life imprisonment. The Protest churches were also purged and their leaders were replaced by those willing to remain loyal to Rakosi's government.

Rakosi had difficulty managing the economy and the people of Hungary saw living standards fall. His government became increasingly unpopular and when Joseph Stalin died in 1953 Matyas Rakosi was replaced as prime minister by Imre Nagy. However, he retained his position as general secretary of the Hungarian Workers Party and over the next three years the two men became involved in a bitter struggle for power.

As Hungary's new leader Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. This included a promise to increase the production and distribution of consumer goods. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact.

Matyas Rakosi led the attacks on Nagy. On 9th March 1955, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Workers Party condemned Nagy for "rightist deviation". Hungarian newspapers joined the attacks and Nagy was accused of being responsible for the country's economic problems and on 18th April he was dismissed from his post by a unanimous vote of the National Assembly. Rakosi once again became the leader of Hungary.

Rakosi's power was undermined by a speech made by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1956. He denounced the policies of Joseph Stalin and his followers in Eastern Europe. He also claimed that the trial of Laszlo Rajk had been a "miscarriage of justice". On 18th July 1956, Rakosi was forced from power as a result of orders from the Soviet Union. However, he did managed to secure the appointment of his close friend, Erno Gero, as his successor.

On 3rd October 1956, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Communist Party announced that it had decided that Laszlo Rajk, Gyorgy Palffy, Tibor Szonyi and Andras Szalai had wrongly been convicted of treason in 1949. At the same time it was announced that Imre Nagy had been reinstated as a member of the Communist Party.

The uprising began on 23rd October by a peaceful manifestation of students in Budapest. The students demanded an end to Soviet occupation and the implementation of "true socialism". The police made some arrests and tried to disperse the crowd with tear gas. When the students attempted to free those people who had been arrested, the police opened fire on the crowd.

The following day commissioned officers and soldiers joined the students on the streets of Budapest. Stalin's statue was brought down and the protesters chanted "Russians go home", "Away with Gero" and "Long Live Nagy". The Central Committee of the Hungarian Communist Party respond to these developments by deciding that Imre Nagy should become head of a new government.

On 25th October Soviet tanks opened fire on protesters in Parliament Square. One journalist at the scene saw 12 dead bodies and estimated that 170 had been wounded. Shocked by these events the Central Committee of the Communist Party forced Erno Gero to resign from office and replaced him with Janos Kadar.

Imre Nagy now went on Radio Kossuth and announced he had taken over the leadership of the Government as Chairman of the Council of Ministers." He also promised the "the far-reaching democratization of Hungarian public life, the realisation of a Hungarian road to socialism in accord with our own national characteristics, and the realisation of our lofty national aim: the radical improvement of the workers' living conditions."

On 28th October, Nagy and a group of his supporters, including Janos Kadar, Geza Lodonczy, Antal Apro, Karoly Kiss, Ferenc Munnich and Zoltan Szabo, manage to take control of the Hungarian Communist Party. At the same time revolutionary workers' councils and local national committees are formed all over Hungary.

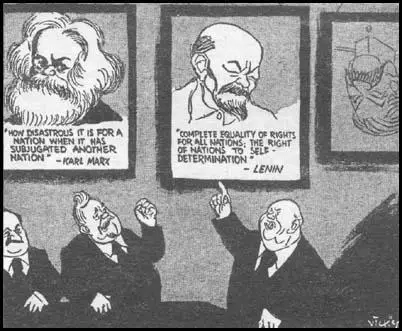

Victor Weisz, Daily Mirror (November, 1956)

The new leadership of the party is reflected in the comments made in its newspaper, Szabad Nep. On 29th October the newspaper defends the change in the government and openly criticises Soviet attempts to influence the political situation in Hungary. This view is supported by Radio Miskolc and it calls for the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country.

On 30th October, Imre Nagy announced that he was freeing Cardinal Joseph Mindszenty and other political prisoners. He also informs the people that his government intends to abolish the one-party state. This is followed by statements by Zolton Tildy, Anna Kethly and Ferenc Farkas concerning the reconstitution of the Smallholders Party, the Social Democratic Party and the Petofi Peasants Party.

Nagy's most controversial decision took place on 1st November when he announced that Hungary intended to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact. as well as proclaiming Hungarian neutrality he asked the United Nations to become involved in the country's dispute with the Soviet Union.

On 3rd November, Nagy announced details of his coalition government. It included communists (Janos Kadar, George Lukacs, Geza Lodonczy), three members of the Smallholders Party (Zolton Tildy, Bela Kovacs and Istvan Szabo), three Social Democrats (Anna Kethly, Gyula Keleman, Joseph Fischer), and two Petofi Peasants (Istvan Bibo and Ferenc Farkas). Pal Maleter was appointed minister of defence.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union, became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. Soviet tanks immediately captured Hungary's airfields, highway junctions and bridges. Fighting took place all over the country but the Hungarian forces were quickly defeated.

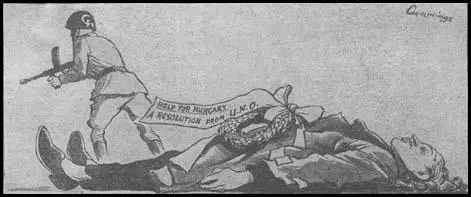

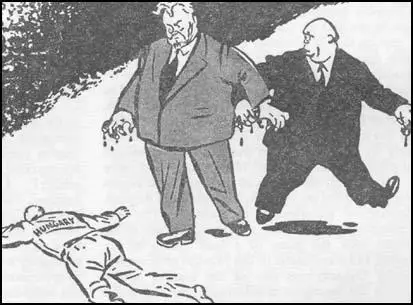

Bombay Express (November, 1956)

Imre Nagy sought and obtained asylum at the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest. So also did George Lukacs, Geza Lodonczy and Julia Rajk, the widow of Laszlo Rajk. Janos Kadar, who claimed that Nagy had gone too far with his reforms, became Hungary's new leader.

It is estimated that about 3,000 Hungarians were killed during the uprising. About 12,000 were arrested and imprisoned. Of these, between 400 and 450 were executed. An estimated 200,000 people managed to escape to the West.

Janos Kadar promised Nagy and his followers safe passage out of the country. Kadar did not keep his promise and on 23rd November, 1956, Nagy and his followers, were kidnapped after leaving the Yugoslav embassy.

On 17th June 1958, the Hungarian government announced that several of the reformers had been convicted of treason and attempting to overthrow the "democratic state order" and Imre Nagy, Pal Maleter and Miklos Gimes had been executed for these crimes. Geza Lodonczy and Attila Szigethy were both to die in suspicious circumstances soon afterwards.

Primary Sources

(1) George Paloczi-Horvath, was arrested by the Hungarian secret police in 1949. He wrote about his experiences in the Daily Herald on 11th December, 1956.

With many thousands of others, I was arrested by the Hungarian secret police (AVO) in the summer of 1949. It was the time when Stalin and his henchmen started to kill off thousands of their followers as part of a ludicrous propaganda drive against Tito. It was also the time when, in Hungary, they started to arrest the Social Democratic leadership and the outstanding non-Muscovite Communists.

I believed then that we would be able to assert our innocence. But I soon found out that our fate was worse than if we had been guilty, because we had nothing to give away in the torture chambers. I was thrown into an icy cold cellar cubicle three yards by four. There was a wooden plank for a bed, and a bright naked electric light glared in my face day and night. Later, it was a great relief to return to this bleak place.

Now I am going to find out the secret of those rigged trials, I thought, when they took me for my first hearing. Two AVO officers questioned me in turn from 9 a.m. till 9 p.m. Then I had to type my life story till 4 a.m. The rest of the 24 hours I had to spend walking up and down in the cubicle because I was not permitted to sleep. This went on for three weeks. The only sleep I got was a few minutes when the guard was slack. The "hearings" soon became tortures. The AVO officers wanted us to invent crimes for ourselves because they knew we were innocent. I won't describe the tortures. There are so many ways to cause piercing pain to the human body. There were days when we were tossed about on a stormy ocean of pain. The torments alone did not make us "confess." Sleeplessness, hunger, utter degradation, filthy insults to human dignity, the knowledge that we were utterly at the mercy of the AVO - all this was not enough. Then they told us they would arrest our wives and children and torment them in front of us. We heard women and children screaming in adjacent rooms. Was this a put-up job for our benefit? I still don't know.

After the first period of torture we were sent back to our solitary cellars for some weeks to "rot away for a while." Now we were tormented by the intense cold, by the glaring bulb and the four walls which threatened to collapse on us. We had to be awake 18 hours a day. There were no books, no cigarettes, only thousands of empty minutes. Our fear now was insanity. Our heads were whirling, we imagined sounds and colours. Some of us had a nightmarish feeling of being drowned. Our emaciated bodies and feverish brains produced eerie visions and hallucinations. Is it a wonder that many of us had no sound judgment, no willpower to resist our tormentors? This torture made some confess. Others went insane, or were clubbed to death. A few held out. I could not bring myself to "confess" - that UNO and the World Federation of United Nations Associations was an imperialist spy and sabotage organisation; that the Hungarian UNA, of which the late Michael Karolyi was president and myself secretary-general, conspired to overthrow the "people's democracy."

After a period of "rotting," a new period of torments started. And so it went on for 13 months.

When at last I signed a ludicrous statement prepared by my tormentors, I was regularly collapsing three or four times a day and had lost more than thirty pounds. I had to confess that John F. Ennals, secretary-general of WFUNA, was my "spy chief" and that I handed him spy reports in Budapest daily from 1947 till the time of my arrest in 1949. During this period Ennals spent only three days in Budapest. He was either at the Geneva headquarters or touring the five continents. When I repeatedly pointed this out to the AVO they said: "Never mind. No word of it will leak out. Your trial will be kept secret."

(2) Stan Newens, International Socialism (12th October, 2006)

The Suez crisis first boomed into view when the Americans and the British refused to finance the Aswan High Dam in Egypt in July 1956. The Egyptian president, Colonel Nasser, thereafter nationalised the Suez Canal....

With the prospect of armed intervention imminent, the Suez Emergency Committee booked Trafalgar Square for an anti-war rally on Sunday 4 November. I was in touch with Peggy Rushton, the MCF general secretary, by phone with the object of helping to mobilise support. On Thursday 1 November, when I phoned, she informed me that the Labour Party had been on the line to take over the booking actually, on behalf of the National Council of Labour, representing the TUC and the co-operative movement as well. I was delighted that she had already agreed and carried on with my plans to rally protesters. In addition, using the Epping CLP duplicator, I copied 6,000 leaflets drafted by myself and my Socialist Review colleagues, calling on workers to strike against the Suez intervention.

The Trafalgar Square rally turned out to be a seminal event in British Labour history. My 6,000 leaflets, which a crowd of dockers helped us to distribute, disappeared in a flash. All afternoon people were pouring into the square until it was impossible to move. At the height of the proceedings, a great chant went up in the north western corner of the square as a massive column of student demonstrators began to come in and went on endlessly...

In Trafalgar Square Mike Kidron, a fellow Socialist Review supporter, told me (as he had left home much later) that the Russians were apparently going in to crush the uprising in Hungary, which had occurred in the latter part of October. The British Communist Party was already in deep crisis. Ever since Nikita Krushchev, the new Soviet leader, had repudiated Soviet changes made under Stalin against Tito in Yugoslavia, which the CPGB leaders had supported, there had been widespread unease. Since then there had been Krushchev’s secret speech to the 20th Congress of the CPSU on 25 February, which the Observer had published in full on 10 June. The Hungarian prime minister, Matyas Rakosi, had confessed that the trial of Laszlo Rajk, a Hungarian Communist leader who had been executed, had been rigged. In Poland Gomulka had assumed power in defiance of Soviet wishes after riots in Poznan in June. The Hungarian revolt had been the last straw, particularly when the case of Edith Bone, a British Communist who had been tortured and ill-treated in a Hungarian prison, hit the news. A huge swathe of Communist Party members were in revolt at the unwavering support given by their leaders to Soviet policy under Stalin.

Peter Fryer, the Daily Worker correspondent in Hungary, sent in reports which the paper refused to publish. It found another journalist, Charlie Coutts, who was prepared to defend Soviet action. Peter Fryer resigned from the Communist Party, wrote a book The Hungarian Tragedy in record time and joined Gerry Healy and his group.

Edward Thompson and John Saville were publishing The Reasoner, a duplicated magazine, which they refused to close down. A third of the Daily Worker’s journalists left. Key trade unionists like John Homer, general secretary of the Fire Brigades Union, Jack Grahl, Leo Keely, Laurence Daly (a leading Scottish miner), Les Cannon of the ETU and many others left the party. The historians Edward Thompson and John Saville quit. Christopher Hill, another historian, who with Peter Cadogan and others produced a minority report on inner party democracy, left afterwards. Besides these and other well known figures, thousands of other members were in revolt.

(3) Peter Fryer, The Hungarian Tragedy (1956)

Look at the hell that Rákosi made of Hungary and you will see an indictment, not of Marxism, not of Communism, but of Stalinism. Hypocrisy without limit; medieval cruelty; dogmas and slogans devoid of life or meaning; national pride outraged; poverty for all but a tiny handful of leaders who lived in luxury, with mansions on Rózsadomb, Budapest's pleasant Hill of Roses (nicknamed by people 'Hill of Cadres'), special schools for their children, special well-stocked shops for their wives - even special bathing beaches at Lake Balaton, shut off from the common people by barbed wire. And to protect the power and privileges of this Communist aristocracy, the A.V.H. - and behind them the ultimate sanction, the tanks of the Soviet Army. Against this disgusting caricature of Socialism our British Stalinists would not, could not, dared not protest; nor do they now spare a word of comfort or solidarity or pity for the gallant people who rose at last to wipe out the infamy, who stretched out their yearning hands for freedom, and who paid such a heavy price.

Hungary was Stalinism incarnate. Here in one small, tormented country was the picture, complete in every detail: the abandonment of humanism, the attachment of primary importance not to living, breathing, suffering, hoping human beings but to machines, targets, statistics, tractors, steel mills, plan fulfilment figures... and, of course, tanks. Struck dumb by Stalinism, we ourselves grotesquely distorted the fine Socialist principle of international solidarity by making any criticism of present injustices or inhumanitites in a Communist-led country taboo. Stalinism crippled us by castrating our moral passion, blinding us to the wrongs done to men if those wrongs were done in the name of Communism. We Communists have been indignant about the wrongs done by imperialism: those wrongs are many and vile; but our one-sided indignation has somehow not rung true. It has left a sour taste in the mouth of the British worker, who is quick to detect and condemn hypocrisy.

(4) Matyas Rakosi, article in the Szabad Nep (19th July, 1956)

My comrades frequently mentioned in the past two years that I do not visit the factories as often as I did in the past. They were right, the only thing they did not know is that this was due to the deterioration of my health. My state of health began to tell on the quality and amount of work I was able to perform, a fact that is bound to cause harm to the Party in such an important post. So much about the state of my health.

A regards the mistakes that I committed in the field of the "cult of personality" and the violation of socialist legality, I admitted them at the meetings of the Central Committee in June, 1953, and I have made the same admission repeatedly ever since. I have also exercised self-criticism publicly.

After the 20th Congress of the CPSU and Comrade Khrushchev's speech it became clear to me that the weight and effect of these mistakes were greater than I had thought and that the harm done to our Party ,through these mistakes was much more serious than I had previously believed.

These mistakes have made our Party's work more difficult, they diminished the strength of attractiveness of the Party and of the People's Democracy, they hindered the development of the Leninist norms of Party life, of collective leadership, of constructive criticism, and self- criticism, of democratism in Party and state life, and of the initiative and creative power of the wide masses of the working class.

Finally, these mistakes offered the enemy an extremely wide opportunity for attack. In their totality, the mistakes that I committed in the most important post of Party work have caused serious harm to our socialist development as a whole.

It was up to me to take the lead in repairing these mistakes. If rehabilitation has at times proceeded sluggishly and with intermittent breaks, if a certain relapse was noticed last year in the liquidation of the cult of personality, if criticism

and self-criticism together with collective leadership have developed at a slow pace, if sectarian and dogmatic views have not been combated resolutely enough - then for all this, undoubtedly, serious reponsibility weighs upon me, having occupied the post of the First Secretary of the Party.

(5) Thomas Schreiber, Le Monde (1956)

The revolution which broke out on the 23rd October on Joseph-Bem-Square started off as a peaceful manifestation. The students' demands, summed up in sixteen points and distributed in the streets of Budapest in the form of leaflets, were those of impatient revolutionary youth.

Certain observers insist on the essentially nationalistic characteristics of the manifestations. Incontestably the presence of the Soviet Army on Hungarian territory, the visible outward signs of foreign occupation (there was no practical difference between Soviet and Hungarian uniforms), rekindled the flame of Hungarian nationalism which had never been extinguished. But it was not only a question of nationalism; the students of Budapest also wanted true socialism.

It was for free independent Socialism that young Hungarians began the struggle against the only armed fascists who on the night of the 23rd October still wished to save their government: the red fascists of the political police, appointed to safeguard the last vestiges of the Stalinist government.

Numerous eye-witnesses have affirmed that at the beginning of the revolution the insurgents had no arms. It was only after Gero's menacing and disastrous speech on his return from Belgrade that the State Police (which must not be confused with the "AVO", or political police) joined the students and distributed arms to them in front of the Hungarian radio broadcasting house in Sandor-Brody Street. Next morning the entire Budapest garrison officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers, joined the students and opened armament depots to them.

The officers responsible were nearly all of them Communists and not "fascist agents or Horthyist officers." The Army's revolt was a result of the turn of events which took place during the night on the banks of the Danube in the neo-Gothic building which overlooks Pariiament.

On the second floor an extraordinary meeting of the Central Committee of the Workers' Party, presided over by Gero, took place at 22.50. Thanks to a personal report by one of the participants, it is possible to give a detailed account of this historic meeting. Assessing the situation, Gero began by trying to convince his colleagues of the necessity of a Soviet intervention, as the "popular forces" were being overwhelmed and the government was in danger. Janos Kadar and then Gyula Kallai (another Titoist who had just been released from prison) replied that the only way to avoid catastrophe was for Gero to resign immediately. Istvan Hidas (Vice President) and Laszlo Piros (Home Secretary) violently opposed this suggestion. Piros referred to Imre Nagy and his friends as "accomplices of the fascists who are at the moment sweeping through the capital."

(6) Seftan Delmer, Daily Express (23rd October, 1956)

I have been the witness today of one of the great events of history I have seen the people of Budapest catch the fire lit in Poznan and Warsaw and come out into the streets in open rebellion against their Soviet overlords. I have marched with them and almost wept for joy with them as the Soviet emblems in the Hungarian flags were torn out by the angry and exalted crowds. And the great point about the rebellion is that it looks like being successful.

As I telephone this dispatch I can hear the roar of delirious crowds made up of student girls and boys, of Hungarian soldiers still wearing their Russian-type uniforms, and overalled factory workers marching through Budapest and shouting defiance against Russia. "Send the Red Army home," they roar. "We want free and secret elections." And then comes the ominous cry which one always seems to hear on these occasions: "Death to Rakosi." Death to the former Soviet puppet dictator - now taking a 'cure' on the Russian Black Sea Riviera - whom the crowds blame for all the ills that have befallen their country in eleven years of Soviet puppet rule.

Leaflets demanding the instant withdrawal of the Red Army and the sacking of the present Government are being showered among the street crowds from trams. The leaflets have been printed secretly by students who "managed to get access", as they put it, to a printing shop when newspapers refused to publish their political programme. On house walls all over the city primitively stencilled sheets have been pasted up listing the sixteen demands of the rebels.

But the fantastic and, to my mind, really super-ingenious feature of this national rising against the Hammer and Sickle, is that it is being carried on under the protective red mantle of pretended Communist orthodoxy. Gigantic portraits of Lenin are being carried at the head of the marchers. The purged ex-Premier Imre Nagy, who only in the last couple of weeks has been readmitted to the Hungarian Communist Party, is the rebels' chosen champion and the leader whom they demand must be given charge of a new free and independent Hungary. Indeed, the Socialism of this ex-Premier and - this is my bet - Premier-soon-to-be-again, is no doubt genuine enough. But the youths in the crowd, to my mind, were in the vast majority as anti-Communist as they were anti-Soviet - that is, if you agree with me that calling for the removal of the Red Army is anti-Soviet.

(7) Tass Soviet News Agency (24th October, 1956)

Late in the evening of October 23 underground reactionary organizations attempted to start a counter-revolutionary revolt against the people's regime in Budapest.

This enemy adventure had obviously been in preparation for some time. The forces of foreign reaction have been systematically inciting anti-democratic elements for action against the lawfulauthority.

Enemy elements made use of the student demonstration that took place on 23 October to bring out into the streets groups previously prepared by them, to form the nucleus of the revolt. They sent agitators into action who created confusion and tried to provoke mass disorder.

A number of governmental buildings and public enterprises were attacked. The fascist thugs who let themselves go began to loot shops, break windows in houses and institutions, and tried to destroy the equipment of industrial enterprises. Groups of rebels who succeeded in getting hold of arms caused bloodshed in a number of places.

The forces of revolutionary order began to repel the rebels. On orders of the reappointed Premier Imre Nagy martial law was declared in the city.

The Hungarian Government asked the USSR Government for help. In accordance with this request, Soviet military units, which are in Hungary under the terms of the Warsaw treaty, helped troops of the Hungarian Republic to restore order in Budapest. In many industrial enterprises workers offered armed resistance to the bandits who tried to damage and destroy equipment and to mount armed guards.

(8) Janos Kadar, Radio Kossuth (24th October, 1956)

Workers, comrades! The demonstration of university youth, which began with the formulation of, on the whole, acceptable demands, has swiftly degenerated into a demonstration against our democratic order; and under the cover of this demonstration an armed attack has broken out. It is only with burning anger that we can speak of this attack by counter-revolutionary reactionary elements against the capital of our country, against our people's democratic order and the power of the working class. Towards the rebels who have risen with arms in their hands against the legal order of our People's Republic, the Central Committee of our Party and our Government have adopted the only correct attitude: only surrender or complete defeat can await those who stubbornly continue their murderous, and at the same time completely hopeless, fight against the order of our working people.

At the same time we are aware that the provocateurs, going into the fight surreptitiously, have been using as cover many people who went astray in the hours of chaos, and especially many young people whom we cannot regard as the conscious enemies of our regime. Accordingly, now that we have reached the stage of liquidating the hostile attack, and with a view to avoiding further bloodshed, we have offered and are offering to those misguided individuals who are willing to surrender on demand, the opportunity of saving their lives and their future, and of returning to the camp of honest people.

(9) Erno Gero, speech (24th October, 1956)

Dear Comrades, Beloved Friends, Working People of Hungary! Of course we want a socialist democracy and not a bourgeois democracy. In accord with our Party and our convictions, our working class and people are jealously guarding the achievements of our people's democracy, and they will not permit anyone to touch them. We shall defend these achievements under all circumstances from whichever quarter they may be threatened. Today the chief aim of the enemies of our people is to shake the power of the working class, to loosen the peasant-worker alliance, to undermine the leadership of the working class in our country and to upset their faith in its party, in the Hungarian Workers' Party. They are endeavouring to loosen the close friendly relations between our nation, the Hungarian People's Republic, and other countries building socialism, especially between our country and the socialist Soviet Union. They are trying to loosen the ties between our party and the glorious Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the party of Lenin, the party of the 20th Congress.

They slander the Soviet Union. They assert that we trade with the Soviet Union on an unequal footing, that our relations with the Soviet Union are not based on equality, and allege that our independence has to be defended, not against the imperialists, but against the Soviet Union. All this is a barefaced lie - hostile slanders which do not contain a grain of truth. The truth is that the Soviet Union has not only liberated our people from the yoke of Horthy fascism and German imperialism, but that even at the end of the war, when our country lay prostrate, she stood by us and concluded pacts with us on the basis of full equality; ever since, she has been pursuing this policy.

(10) The Manchester Guardian (25th October, 1956)

The 5,000 students who were meeting in front of the Petofi Monument in Budapest were joined shortly after dusk by thousands of workers and others. The great crowd then marched to the Stalin monument. Ropes were wound round the statue's neck, and, to cheers, the crowd attempted to topple the statue. But it would not budge. They finally managed to melt Stalin's knees by using welding torches.

(11) Imre Nagy, Radio Kossuth (25th October, 1956)

People of Budapest, I announce that all those who cease fighting before 14.00 today, and lay down their arms in the interest of avoiding further bloodshed, will be exempted from martial law. At the same time I state that as soon as possible and by all the means at our disposal, we shall realise, on the basis of the June 1953 Government program which I expounded in Parliament at that time, the systematic democratization of our country in every sphere of Party, State, political and economic life. Heed our appeal. Cease fighting, and secure the 'restoration of calm and order in the interest of the future of our people and nation. Return to peaceful and creative work!

Hungarians, Comrades, my friends! I speak to you in a moment filled with responsibility. As you know, on the basis of the confidence of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Workers' Party and the Presidential Council, I have taken over the leadership of the Government as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Every possibility exists for the Government to realise my political program by relying on the Hungarian people under the leadership of the Communists. The essence of this program, as you know, is the far-reaching democratization of Hungarian public life, the realisation of a Hungarian road to socialism in accord with our own national characteristics, and the realisation of our lofty national aim: the radical improvement of the workers' living conditions.

However, in order to begin this work - together with you - the first necessity is to establish order, discipline and calm. The hostile elements that joined the ranks of peacefully demonstrating Hungarian youth, misled many well-meaning workers and turned against the people's democracy, against the power of the people. The paramount task facing everyone now is the urgent consolidation of our position. Afterwards, we shall be able to discuss every question, since the Government and the majority of the Hungarian people want the same thing. In referring to our great common responsibility for our national existence, I appeal to you, to every man, woman, youth, worker, peasant, and intellectual to stand fast and keep calm; resist provocation, help restore order, and assist our forces in maintaining order. Together we must prevent bloodshed, and we must not let this sacred national program be soiled by blood.

(12) Peter Fryer, The Hungarian Tragedy (1956)

The troops in Budapest, as later in the provinces, were of two minds: there were those who were neutral and there were those who were prepared to join the people and fight alongside them. The neutral ones (probably the minority) were prepared to hand over their arms to the workers and students so that they could do battle against the A.V.H. with them. The others brought their arms with them when they joined the revolution. Furthermore, many sporting rifles were taken by the workers from the factory armouries of the Hungarian Voluntary Defence Organisation. The "mystery" of how the people were armed is no mystery at all. No one has yet been able to produce a single weapon manufactured in the West.

The Hungarian Stalinists, having made two calamitous mistakes, now made a third - or rather, it would be charitable to say, had it thrust on them by the Soviet Union. This was the decision to invoke a non-existent clause of the Warsaw Treaty and call in Soviet troops. This first Soviet intervention gave the people's movement exactly the impetus needed to make it united, violent and nation-wide. It seems probable, on the evidence, that Soviet troops were already in action three or four hours before the appeal, made in the name of Imre Nagy as his first act on becoming Prime Minister. That is debatable, but what is not debatable is that the appeal was in reality made by Gero and Hegedus; the evidence of this was later found and made public. Nagy became Prime Minister precisely twenty-four hours too late, and those who throw mud at him for making concessions to the Right in the ten days he held office should consider the appalling mess that was put into his hands by the Stalinists when, in desperation, they officially quit the stage.

With Nagy in office it would still have been possible to avert the ultimate tragedy if the people's two demands had been met immediately - if the Soviet troops had withdrawn without delay, and if the security police had been disbanded. But Nagy was not a free agent during the first few days of his premiership. It was known in Budapest that his first broadcast were made - metaphorically, if not literally - with a tommy-gun in his back.

(13) Noel Barber, Daily Mail (27th October, 1956)

Tonight Budapest is a city of mourning. Black flags hang from every window. For during the past four days thousands of its citizens fighting to throw off the yoke of Russia have been killed or wounded. Budapest is a city that is slowly dying. Its streets and once-beautiful squares are a shamble of broken glass, burnt-out cars and tanks, and rubble. Food is scarce, petrol is running out.

But still the battle rages on. For five hours this morning until a misty dawn broke over Budapest I was in the thick of one of the battles. It was between Soviet troops and insurgents trying to force a passage across the Danube.

Two of the rebels into whose ranks I literally wandered died in the battle, one of them in my arms. Several were wounded. Tonight, as I write this dispatch, heavy firing is shaking the city, which is still sealed off from the rest of the world.

To get here I drove through endless Russian check points and through fighting that has now killed thousands of civilians. Where formerly the trams ran, the insurgents have torn up the rails to use as anti-tank weapons. At least 70 tanks have been smashed so far, many with Molotov cocktails. Their burnt-out skeletons seem everywhere, spread on both sides of the Danube. Even trees have been dug out as anti-tank barricades. Burned-out cars are used by the rebels at every street corner, but still the Soviet tanks are rumbling through the city. There are at least 50 still in action, together with armoured cars and troop carriers. They fire on anything, almost at sight.

At the moment I can hear, like thunder rolling in the distance, the sound of their 85 mm. guns. They are battling for some objective which sounds about a quarter of a mile away. The Chain Bridge probably. The insurgents have plenty of ammunition, stored in a central dump, but it is all for automatic weapons and the making of Molotov Cocktails.

Travelling around the city is a nightmare, for no one knows who is friend or foe, and all shoot at everybody. There is no doubt now the revolt has been far more bloody than the official radio reports suggested. Casualties number many thousands. The Russian are just unloosing murder at every street corner.... I owe my life to a young girl insurgent who, speaking a little English, helped me to safety after the Russians had opened fire on my car.

It took me three hours to drive from the border to the outskirts of Buda, the hilly part of Budapest. Twice on the way I was stopped by Soviet troops. But each time I persuaded them to let me through. I made for the Chain Bridge that spans the Danube. In front of the bridge stood a barricade of burned out tramcars, a bus, old cars, and uprooted tramlines. It was at least the 50th barricade of its kind I had seen since I entered the city. As I drove towards it, lights full on and the Chain Bridge on my left, heavy Bring started from the centre of the bridge. Machine-gun bullets whistled past the car. Then, when some heavier stuff began falling I switched off the lights, jumped out and crawled round to the side.

It was foggy. For ten minutes the firing, in a desultory fashion, went on. Then I heard a whispered voice - a woman's. She spoke first in German, crawled round to where I was crouching, then in halting English told me to get back in my car. She herself, walking, crouched by the car, guided me into a side street. Then, together, we darted back to the road-block.

I found nine boys there, their average age about 18. Three wore Hungarian uniform, but with the hated Red Star torn off. Others wore red, green, and white armbands, the national colours of Hungary. All had sub-machine guns. Their pockets were filled with ammunition. The girl, whose name I discovered was Paula, had a gun too.

Half-way across the bridge I could see the dim outlines of two Soviet tanks. For an hour they fired at us. But never a direct hit - a shell smashed straight through the bus. One of the boys was killed instantly. I tried to help a second boy who was hurt, but he died five minutes later. The shelling went on. We crouched under cover and only splinters hit us. The rebels kept up machine-gun fire all the time. Paula was wounded in the arm, but not seriously. I helped her dress it with one of my handkerchiefs.

"Now you see what we are fighting against", said Paula. She was wearing slacks, bright blue shoes, and a green overcoat.

"We will never give in - never", she said.

"Never until the Russians are out of Hungary and the AVH (she pronounced it Avo) is dissolved".

(14) John MacCormac, New York Times (27th October, 1956)

It looked Wednesday as if the intervention of Soviet troops, who had been called in at 4.30 o'clock that morning, had quelled the revolt. The Soviet forces had eighty tanks, artillery, armored cars and other equipment of a variety normally possessed only by a complete Soviet mechanized division. The insurgent Hungarian students and workers at no time had more than small arms furnished by sympathizing soldiers of the Hungarian Army.

What revived the revolt was a massacre. Since only a few minutes earlier Soviet tank crews had been fraternizing with insurgents, it is possible that the massacre was a tragic mistake. The most credible version is that the political policemen opened fire on the demonstrators and panicked the Soviet tank crews into the belief that they were being attacked.

But in any case when the firing subsided Parliament Square was littered with dead and dying men and women. The total number of casualties has been estimated at 170. This correspondent can testify that he saw a dozen bodies.

Far from deterring the demonstration, the firing embittered and inflamed the Hungarian people. A few minutes later and only a few blocks from the scene of the massacre, the surviving demonstrators reassembled in Szabadsag (the word means liberty) Square. When trucks filled with Hungarian soldiers drove up and warned the demonstrators that they were armed, the leader of the demonstrators brandished a Hungarian flag and replied: "We are armed only with this, but it is enough".

On a balcony above appeared an elderly Hungarian clad in pyjamas and a dressing gown and clasping a huge flag. He threw it down to the demonstrators.

Another man mounted a ladder to tear down the Soviet emblem from the "Liberty" monument in "Liberty" square. It was erected in 1945 by the Russians with forced Hungarian labor.

A crowd assembled before the United States legation in the square and shouted: "The workers are being murdered, we want help." Finally Spencer Bames, Charge d'Affaires, told them that their case was one for decision by his Government and the United Nations, not for the local staff. The British Minister had received a deputation and given it the same message.

Among those watching this demonstration was a furtive figure clad in a leather coat. Suddenly someone identified him rightly or wrongly as a member of the hated AVO, the Hungarian political police. Like tigers the crowd turned on him, began to beat him and hustled him into a courtyard. A few minutes later they emerged rubbing their hands with satisfaction. The leather-coated figure was seen no more.

During all these activities and while Soviet tanks continued to race through near-by streets firing their fusillades, the crowd never ceased shouting: "Down with Gerol" Less than an hour later the radio announced that Mr. Gero had been replaced by Janos Kadar, former Interior Minister and second secretary of the party.

(15) New York Times (28th October, 1956)

The Daily Worker, New York Communist newspaper, terms the use of Soviet troops in Hungary "deplorable" today and calls for the end of the fighting in that country... The editorial says, "the delay of the Hungarian Communists in developing their own path played into the hands of the counter-revolutionaries". After asserting the Soviet troops in Hungary had been used at the request of the Hungarian Government, the editorial added its only note of protest - "which does not, however, in our view, make the use of Soviet troops in Hungary any the less deplorable."

(16) George Lukacs, Radio Kossuth (28th October, 1956)

I consider it of great importance that a Government has been formed representing every shade and stratum of the Hungarian people that wants progress and socialism. It was a great mistake of the previous regime to become isolated from those creative elements with whose help the Hungarian road to socialism could have been successfully taken. The main task of the new Government is to make a most radical break with narrow-minded and petty trends, and to make use of every sound popular initiative, so that every true Hungarian can look upon the socialist fatherland as his own. The task of the Ministry of People's Culture is the realisation of these principal aims in the sphere of culture. The Hungarian people have an exceptionally rich tradition in almost every field of culture. We do not want to build socialism out of air; we do not want to bring it into Hungary as an imported article. What we want is that the Hungarian people work out, organically, and by long, glorious and successful work, a socialist culture worthy of the Hungarian people's great and ancient achievements, and which, as a socialist culture, can place Hungarian culture on even broader foundations with even deeper roots.

(17) Radio Kossuth (28th October, 1956)

The Government has instructed the Minister of Education without delay to withdraw from circulation all history textbooks. In other textbooks, all passages impregnated with the spirit of the personality-cult must be rectified by teachers in the course of instruction.

(18) Imre Nagy, Radio Kossuth (30th October, 1956)

Hungarian workers, soldiers, peasants and intellectuals. The constantly widening scope of the revolutionary movement in our country, the tremendous force of the democratic movement has brought our country to a cross-road. The National Government, in full agreement with the Presidium of the Hungarian Workers' Party, has decided to take a step vital for the future of the whole nation, and of which I want to inform the Hungarian working people.

In the interest of further democratization of the country's life, the cabinet abolishes the one-party system and places the country's Government on the basis of democratic cooperation between coalition parties as they existed in 1945. In accordance with this decision a new national government - with a small inner cabinet - has been established, at the moment with only limited powers.

The members of the new Cabinet are Imre Nagy, Zoltan Tildy, Bela Kovacs, Ferenc Erdei, Janos Kadar, Geza Losonczy and a person whom the Social Democratic Party will appoint later.

The government is going to submit to the Presidential Council of the People's Republic its proposition to appoint Janos Kadar and Geza Losonczy as Ministers of State.

This Provisional Government has appealed to the Soviet General Command to begin immediately with the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the territory of Budapest. At the same time, we wish to inform the people of Hungary that we are going to request the Government of the Soviet Union to withdraw Soviet troops completely from the entire territory of the Hungarian Republic.

On behalf of the National Government I wish to declare that it recognizes all autonomous, democratic, local authorities which were formed by the revolution; we will rely on them and we ask for their full support.

Hungarian brothers, patriotic citizens of Hungary! Safeguard the achievements of the revolution! We have to re-establish order first of all! We have to restore peaceful conditions! No blood should be shed by fratricide in our country! Prevent all further disturbances! Assure the safety of life and property with all your might!

Hungarian brothers, workers and peasants: Rally behind the government in this fateful hour! Long live free, democratic and independent Hungary.

(19) Janos Kadar, Radio Kossuth (30th October, 1956)

My fellow-workers, working brethren, dear comrades! Moved by the deep sense of responsibility to spare our nation and working masses further bloodshed, I declare that every member of the Presidium of the Hungarian Workers' Party agrees with today's decisions by the Council of Ministers. As for myself, I can add that I am in wholehearted agreement with those who spoke before me, Imre Nagy, Zoltan Tildy and Ferenc Erdei. They are my acquaintances and friends, my esteemed and respected compatriots.

I address myself to the Communists, to those Communists who were prompted to join the Party by the progressive ideas of mankind and socialism, and not by selfish personal interests - let us represent our pure and just ideas by pure and just means.

My comrades, my fellow workers! Bad leadership during the past years has cast on our Party the shadow of great and grave burdens. We must fully rid ourselves of these burdens, of all accusations against the Party. This must be done with a clear conscience, with courage and straight-forward resolution. The ranks of the Party will thin out, but I do not fear that pure, honest and well-meaning Communists will be disloyal to their ideals. Those who joined us for selfish personal reasons, for a career or other motives will be the ones to leave. But, having got rid of this ballast and the burden of past crimes by certain persons in our leadership, we will fight, even if to some extent from scratch, under more favourable and clearer conditions for the benefit of our ideas, our people, our compatriots and country.

I ask every Communist individually to set an example, by deeds and without pretense, a real example worthy of a man and a Communist, in restoring order, starting normal life, in resuming work and production, and in laying the foundations of an ordered life. Only with the honour thus acquired can we earn the respect of our other compatriots as well.

(20) Peter Fryer, The Hungarian Tragedy (1956)

Even the children, hundreds of them, had taken part in the fighting, and I spoke to little girls who had poured petrol in the path of Soviet tanks and lit it. I heard of 14-year-olds who had jumped to their deaths on to the tanks with blazing petrol bottles in their hands. Little boys of twelve, armed to the teeth, boasted to me of the part they had played in the struggle. A city in arms, a people in arms, who had stood up and snapped the chains of bondage with one gigantic effort, who had added to the roll-call of cities militant - Paris, Petrograd, Canton, Madrid, Warsaw - another immortal name. Budapest! Her buildings might be battered and scarred, her trolley-bus and telephone wires down, her pavements littered with glass and stained with blood. But her citizens' spirit was unquenchable.

(21) Imre Nagy, Radio Kossuth (31st October, 1956)

Here is an important announcement: The Hungarian National Government wishes to state that the proceedings instituted in 1948 against Jozsef Mindszenty, Cardinal Primate, lacked all legal basis and that the accusations levelled against him by the regime of that day were unjustified. In consequence the Hungarian National Government announces that the measures depriving Cardinal Primate Jozsef Mindszenty of his rights are invalid and that the Cardinal is free to exercise without restriction all his civil and ecclesiastical rights.

(22) Janos Kadar, Radio Kossuth (1st November, 1956)

In their glorious uprising our people have shaken off the Rakosi regime. They have achieved freedom for the people and independence for the country. Without this there can be no socialism. We can safely say that the ideological and organisational leaders who prepared this uprising were recruited from among your ranks. Hungarian Communist writers, journalists, university students, the youth of the Petofi Circle, thousands and thousands of workers and peasants, and veteran fighters who had been imprisoned on false charges, fought in the front line against Rakosiite despotism and political hooliganism.

In these momentous hours the Communists who fought against the despotism of Rakosi have decided, in accordance with the wish of many true patriots and socialists, to form a new Party. The new Party will break away from the crimes of the past for once and for all. It will defend the honour and independence of our country against anyone. On this basis, the basis of national independence, it will build fraternal relations with any progressive socialist movement and party in the world.

In these momentous hours of our history we call on every Hungarian worker who is led by devotion to the people and the country to join our Party, the name of which is the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party. The Party counts on the support of every honest worker who declares himself in favour of the socialist objectives of the working class. The Party invites into its ranks every Hungarian worker who adopts these principles and who is not responsible for the criminal policy and mistakes of the Rakosi-clique. We expect everybody to join who, in the past, was deterred from service to socialism by the anti-national policy and criminal deeds of Rakosi and his followers.

(23) Joseph Mindszenty, speech (1st November, 1956)

Nowadays it is often emphasized that the speaker breaking away from the practice of the past is speaking sincerely. I cannot say this in such a way. I need not break with my past; by the grace of God I am the same as I was before my imprisonment. I stand by my conviction physically and spiritually intact, just as I was eight years ago, although imprisonment has left its mark on me. Nor can I say that now I will speak more sincerely, for I have always spoken sincerely.

Now is the first instance in history that Hungary is enjoying the sympathy of all civilized nations. We are deeply moved by this. A small nation has heartfelt joy that because of its love of liberty the other nations have taken up its cause. We see Providence in this, expressed by the solidarity of foreign nations just as it says in our national anthem: "God bless the Hungarian - reach out to him Thy protective hand." Then our national anthem continues; "when he is fighting against his enemy." But we, even in our extremely severe situation, hope that we have no enemy! For we are not enemies of anyone. We desire to live in friendship with every people and with every country.

We, the little nation, desire to live in friendship and in mutual respect with the great American United States and with the mighty Russian Empire alike, in good neighborly relationship with Prague, Bucharest, Warsaw, and Belgrade. In this regard I must mention that for the brotherly understanding in our present suffering every Hungarian has embraced Austria to his heart.

And now, our entire position is decided by what the Russian Empire of 200 millions intends to do with the military force standing within our frontiers. Radio announcements say that this military force is growing. We are neutral, we give the Russian Empire no cause for bloodshed. But has the idea not occurred to the leader of the Russian Empire that we will respect the Russian people far more if it does not oppress us. It is only an enemy people which is attacked by another country. We have not attacked Russia and sincerely hope that the withdrawal of Russian military forces from our country will soon occur.

This has been a freedom fight which was unparalleled in the world, with the young generation at the head of the nation. The fight for freedom was fought because the nation wanted to decide freely on how it should live. It wants to be free to decide about the management of its state and the use of its labor. The people themselves will not permit this fact to be distorted to the advantage of some unauthorized powers or hidden motives. We need new elections - without abuses - at which every party can nominate.

(24) George Paloczi-Horvath, Daily Herald (4th November, 1956)

It was dawn . . . the day the Russians struck again. We were awakened by the roar of heavy guns. The radio was a shambles. All we got was the national anthem, played over and over again, and continual repetition of Premier Nagy's announcement that after a token resistance we must cease fighting and appeal to the free world for help.

After our ten days' war of liberty; after the pathetically short period of our 'victory', this was a terrible blow. But there was not time to sit paralysed in despair. The Russians had arrested General Maleter, head of the Central Revolutionary Armed Forces Council. The Army had received ceasefire orders. But what of the fighting groups of workers and students?

These courageous civilian units now had to be told to put up only token resistance in order to save bloodshed. They had been instructed not to start firing.

I called up the biggest group, the 'Corvin regiment.' A deputy commander answered the phone. His voice was curiously calm: "Yes, we realized we should not open fire. But the Russians did. They took up positions around our block and opened fire with everything they had. The cellars are filled with 200 wounded and dead. But we will fight to the last man. There is no choice. But inform Premier Nagy that we did not start the fight."

This was just before seven in the morning. Premier Nagy, alas, could not be informed any more. He was not to be found.

The situation was the same everywhere. Soviet tanks rolled in and started to shoot at every centre of resistance which had defied them during our first battle for freedom. This time, the Russians shot the buildings to smithereens. Freedom fighters were trapped in the various barracks, public buildings and blocks of flats. The Russians were going to kill them off to the last man. And they knew it. They fought on till death claimed them.

This senseless Russian massacre provoked the second phase of armed resistance. The installation of Radar's puppet government was only oil on the fire. After our fighting days, after our brief span of liberty and democracy. Radar's hideous slogans and stupid lies, couched in the hated Stalinite terminology, made everyone's blood boil. Although ten million witnesses knew the contrary, the puppet government brought forward the ludicrous lie that our war of liberty was a counter-revolutionary uprising inspired by a handful of Fascists.

The answer was bitter fighting and a general strike throughout the country. In the old revolutionary centres - the industrial suburbs of Csepel, Ujpest and the rest - the workers struck and fought desperately against the Russian tanks.

Posters on the walls challenged the lies of the puppet Government: "The 40,000 aristocrats antifascists of the Csepel works strike on!" said one of them.

"The general strike is a weapon which can be used only when the entire working class is unanimous - so don't call us Fascists,'" said another.

Armed resistance stopped first. The Russians bombarded to rubble every house from which a single shot was fired. The fighting groups realized that further battles would mean the annihilation of the capital. So they stopped fighting.

But the strike went on.

(25) Leslie Bain's interview with Bela Kovacs appeared in the New York Reporter on 13th December, 1956.

Late in the evening of Sunday, November 4 - a night of terror in Budapest that no one who lived through it will ever forget - I met Bela Kovacs, one of the leaders of Hungary's short-lived revolutionary government, in a cellar in the city's center.

Kovacs, as a Minister of State of the Nagy regime, had started oft for the Parliament Building early that morning, but he never reached it. Soviet tanks were there ahead of him. Now he squatted on the floor opposite me, a fugitive from Soviet search squads.

A hunched, stocky man, with a thin mustache and half-closed eyes, Bela Kovacs was only a shadow of the robust figure he once had been. Now in his early fifties, he had risen to prominence after the war as one of the top leaders of the Hungarian Independent Smallholders Party. Back in 1947, when Matyas Rakosi began taking over the government with the support of the Soviet occupation forces, Kovacs had achieved fame by being the only outstanding anti-Communist Hungarian leader to defy Rakosi and continue open opposition. His prestige had become so great among the peasantry that at first the Communists had not molested him. But then the Soviets themselves stepped in, arresting him on a trumped-up charge of plotting against the occupation forces and sentencing him to life imprisonment. After eight years in Siberia, Kovacs was returned to Hungary and transferred to a Hungarian jail, from which he was released in the spring of 1956, broken in body but not in spirit by his long ordeal. After what was called his "rehabilitation," Kovacs was visited by his old enemy Rakosi, who called to pay his respects. Rakosi was met at the door by this message from Kovacs: "I do not receive murderers in my home."

So long as Nagy's government was still under the thumb of the Communist Politburo, Kovacs refused to have anything to do with the new regime. Only in the surge of the late October uprising, when Nagy succeeded in freeing himself from his former associates and cast about to form a coalition government, did Kovacs consent to lend his name and immense popularity to it.

I asked Kovacs whether he felt the Nagy government's declaration of neutrality had aroused the Soviet leaders to action. No, he thought that the decision to crush the Hungarian revolution was taken earlier and independently of it. Obviously the Russians would not have rejoiced at a neutral Hungary, but so long as economic cooperation between the states in the area was assured the Russians and their satellites should not have been too unhappy.

In that regard, Kovacs assured me, there was never a thought in the Nagy government of interrupting the economic co-operation of the Danubian states. "It would have been suicidal for us to try tactics hostile to the bloc. What we wanted was simply the right to sell our product to the best advantage of our people and buy our necessities where we could do it most advantageously."

"Then in your estimation there was no reason why the Russians should have come again and destroyed the revolution?"

"None unless they are trying to revert to the old Stalinist days. But if that is what they really are trying - and at the moment it looks like it - they will fail, even more miserably than before. The tragedy of all this is that they are burning all the bridges which could lead to a peaceful solution."

How much truth was in the Russian assertion that the revolution had become a counter-revolution and that therefore Russian intervention was justified?

"I tell you," said Kovacs, "this was a revolution from inside, led by Communists. There is not a shred of evidence that it was otherwise. Communists outraged by their own doings prepared the ground for it and fought for it during the first few days. This enabled us former non-Communist party leaders to come forward and demand a share in Hungary's future. Subsequently this was granted by Nagy, and the Social Democratic, Independent Smallholders, and Hungarian Peasant parties were reconstituted. True, there was a small fringe of extremists in the streets and there was also evidence of a movement which seemed to have ties with the exiled Nazis and Nyilas of former days. But at no time was their strength such as to cause concern. No one in Hungary cares for those who fled to the West after their own corrupt terror regime was finished - and then got their financing from the West. Had there been an attempt to put them in power, all Hungary would haven risen instantly ..."

"What of the future?" I asked. After some hesitation Kovacs said: "All is not lost, for it is impossible for the Russians and their puppets to maintain themselves against the determined resistance of the Hungarians. The day will come when a fateful choice will have to be made: Exterminate the entire population by slow starvation and police terror or else accept the irreducible demand - the withdrawal of Soviet forces from our country."

(26) Marshall Zhukov, Tass Radio Station (7th November, 1956)

Comrade soldiers and sailors, sergeants and petty officers! Comrade officers, generals and admirals! Working people of the Soviet Union! Our dear foreign guests I greet and congratulate you on the occasion of the 39th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution! ... Rallied closely behind the Party and the Government, which are resolutely implementing Lenin's behests, the Soviet people will spare no efforts or creative energy in the struggle for the continued flourishing of our socialist homeland.

In its foreign policy, the Soviet Union has invariably proceeded from the principle of the peaceful co-existence of countries with different social systems, from the great aim of preserving world peace.

However, the enemies of socialism, the enemies of peaceful co-existence and friendship of the peoples, proceed with their actions designed to undermine the friendly relations between the peoples of the Soviet Union and the peoples of other countries, to frustrate the noble aims of peaceful co-existence on the basis of complete sovereignty and equality. This is confirmed by the armed aggression by Britain, France and Israel against the independent Egyptian State and by the actions of the counter-revolutionary forces in Hungary aimed at overthrowing the system of people's democracy and restoring fascism in the country. The patriots of people's Hungary, together with the units of the Soviet Army called in to assist the revolutionary workers' and peasants' Government, firmly barred the road to reaction and fascism in Hungary ...

Long live our mighty Soviet Homeland! Long live the heroic Soviet people and its armed forces! Long live our Soviet Government! Glory to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the inspirer and organiser of all our visitors!

(27) Manchester Guardian (14th November, 1956)

The fighting in Budapest is over. The streets are crowded. It is at once a city at peace and a city at war. The crowds in the streets, the workers of the factories, have no thought of resuming work. The people filling the city's main thoroughfares are part of a huge silent demonstration of protest. In an unending line they file past the damaged and destroyed houses, silently point to the shell holes and heaps of rubble that were once walls, and pass on.

The workers are streaming back to the factories but only to collect their pay - in most cases 50 per cent of their wages - and then go home. Sometimes they assemble for mass meetings in their factories, where resolutions are passed demanding an immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops, the formation of a Government under Imre Nagy, the admission of United Nations observers into the country, the establishment of a neutral Hungary, and free elections - though this last point is omitted in some resolutions. No work will be done except by public facilities and food services, the resolutions say, until the workers' demands have been conceded.

Leaflets, some of them printed, some cyclo-styled, spread the texts of these resolutions through the city. Government posters calling for a return to work are plastered over with these leaflets and with smaller handwritten posters calling for a continuation of the general strike.

The fighting in Budapest is over but the fight is on. And it is a grimmer fight than during the days when shells were whizzing past and boys and girls with Molotov cocktails were throwing themselves at Soviet tanks.

For, while limited supplies of food are available, the refusal of the fathers to work means starvation both for young and old and death for the weakest. Indeed, the youngest and the oldest and the infirm, deprived of the minimum food they need and of the medical attention that goes in the first place to the wounded freedom fighters, are dying in greater numbers than in more normal times. These deaths, like the deaths resulting from the actual fighting, are the logical consequences of the decision taken by the whole nation to carry on the fight.

The general strike through which this fight is now carried on is a murderous weapon both for those who use it and for those against whom it is directed. For the Kadar Government, supported only by Soviet tanks, is being killed as effectively as if each of its members were strung up from a lamp-post. The people taking part in this strike realise full well that what they are doing is madness, that they are not harming the Russians by their strike but only themselves. Yet there is method in their madness. They cannot believe that the West will stand by and witness passively the slow suicide of a whole nation.

(28) Josip Tito, speech (16th November, 1956)

Things had already gone rather far, further than we knew, and Gero's visit to Yugoslavia and our joint declaration could no longer help. People in Hungary were absolutely against the Stalinist elements still in power; they asked for their removal and a turn to the road of democratization. When the Hungarian delegation headed by Gero returned to their country, Gero found himself in a difficult position and again showed his previous face. He called those hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, who at that time were still demonstrating, a gang and insulted almost the whole nation. Imagine how blind he was, what kind of a leader he was! At such a critical moment, when everything boils and when the whole nation is discontented, he dares to call that nation a gang, among whom a great number, and perhaps a majority were communists and young people. This was enough to blow up the powder-keg. Conflicts took place.

The point now is not to examine who fired the farst shot. Gero called the army. It was a fatal mistake to call Soviet troops at the time when demonstrations were still going on. To call upon troops of another country to give lessons to the people of one's own country, even if shooting takes place, is a great mistake. This made the people even more furious and this is how a spontaneous uprising came about.

(29) Milovan Djilas, New Leader (19th November, 1956)

The experience of Yugoslavia appears to testify that national Communism is incapable of transcending the boundaries of Communism as such, that is, to institute the kind of reforms that would gradually transform and lead Communism to freedom. That experience seems to indicate that national Communism can merely break from Moscow and, in its own national tempo and way, construct essentially the identical Communist system. Nothing would be more erroneous, however, than to consider these experiences of Yugoslavia applicable to all countries of Eastern Europe.

The resistance of the leaders encouraged and stimulated the resistance of the masses. In Yugoslavia, therefore, the entire process was led and carefully controlled from above, and tendencies to go farther - to democracy - were relatively weak. If its revolutionary past was an asset to Yugoslavia while she was fighting for independence from Moscow, it became an obstacle as soon as it became necessary to move forward - to political freedom.

Yugoslavia supported this discontent as long as it was conducted by the Communist leaders, but turned against it - as in Hungary - as soon as it went further. Therefore, Yugoslavia abstained in the United Nations Security Council on the question of Soviet intervention in Hungary. This revealed that Yugoslav national Communism was unable in its foreign policy to depart from its narrow ideological and bureaucratic class interests, and that, furthermore, it was ready to yield even those principles of equality and non-interference in internal affairs on which all its successes in the struggle with Moscow had been based.

The Communist regimes of the East European countries must either begin to break away from Moscow, or else they will become even more dependent. None of the countries - not even Yugoslavia - will be able to avert this choice. In no case can the mass movement be halted, whether if follows the Yugoslav-Polish pattern, that of Hungary, or some new pattern which combines the two.

Despite the Soviet repression in Hungary, Moscow can only slow down the processes of change; it cannot stop them in the long run. The crisis is not only between the USSR and ifs neighbors, but within the Communist.

(30) Raymond Aron, article in Demain (22nd November, 1956)

There are circumstances in political life when discreet expression becomes intolerable. One feels the need to say all one has to say, or rather to cry out one's feelings and one's thoughts. Far from feeling ashamed of the emotions that affect us, we would be angry with ourselves not to feel them. Even if, when some time has elapsed, we can look at things with a clearer head and we put the merits and blame on other shoulders, we will never regret that today's judgment was clearly defined.

In the course of the first few days of November we reached the depths of political despair. The fact that France and England were accused by all the nations of the world whilst Soviet tanks massacred the people who claimed the right to live in freedom, and that Europe's protest was half smothered and half disqualified by the landings in Egypt, represents an historical disaster, for which we shall feel remorse for a long time to come.

Let us be blunt: everything that we have since learned leaves no doubt in our minds as to the hypocrisy of the Russians when they resolved to repress the rising. The evacuation of Budapest was only a war stratagem and the tanks which left then occupied strategic positions. Russian troop movements had begun before the Franco-British ultimatum ... Yes, but Hungarians coming from Budapest told me: "When we learned of the Franco-British ultimatum, we knew that we were lost." Throughout the world, millions of people continue to ask themselves: "Would they have dared if ..." This question, even if we do not hesitate over the answer, will torture our consciences. I admire those who are not troubled by it.

(31) Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beavoir, Roger Vaillant, Claude Roy, and others, France-Observateur (15th November, 1956)

The undersigned who never harbored unfriendly feelings to the U.S.S.R. and socialism, today consider themselves justified in protesting to the Soviet Government against the use of guns and tanks to suppress the uprising of the Hungarian people and its striving to independence, even taking into account the fact that some reactionary elements, which made appeals on the rebel radio, were involved.

We consider and always will consider that socialism, like freedom, cannot be carried on the point of a bayonet. We fear that a government, imposed by force, will soon be compelled, in order to stand its ground, to resort to force itself and to the injustices against its own people which ensue from this.

(32) Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (1995)

Khrushchev's secret speech at the XXth Party Congress caused a political and psychological shock throughout the country. At the Party krai committee I had the opportunity to read the Central Committee information bulletin, which was practically a verbatim report of Khrushchev's words. I fully supported Khrushchev's courageous step. I did not conceal my views and defended them publicly. But I noticed that the reaction of the apparatus to the report was mixed; some people even seemed confused.

I am convinced that history will never forget Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin's personality cult. It is, of course, true that his secret report to the XXth Party Congress contained scant analysis and was excessively subjective. To attribute the complex problem of totalitarianism simply to external factors and the evil character of a dictator was a simple and hard-hitting tactic - but it did not reveal the profound roots of this tragedy. Khrushchev's personal political aims were also transparent: by being the first to denounce the personality cult, he shrewdly isolated his closest rivals and antagonists, Molotov, Malenkov, Kaganovich and Voroshilov - who, together with Khrushchev, had been Stalin's closest associates.

True enough. But in terms of history and 'wider polities' the actual consequences of Khrushchev's political actions were crucial. The criticism of Stalin, who personified the regime, served not only to disclose the gravity of the situation in our society and the perverted character of the political struggle that was taking place within it - it also revealed a lack of basic legitimacy. The criticism morally discredited totalitarianism, arousing hopes for a reform of the system and serving as a strong impetus to new processes in the sphere of politics and economics as well as in the spiritual life of our country. Khrushchev and his supporters must be given full credit for this. Khrushchev must be given credit too for the rehabilitation of thousands of people, and the restoration of the good name of hundreds of thousands of innocent citizens who perished in Stalimst prisons and camps.

Khrushchev had no intention of analysing systematically the roots of totalitarianism. He was probably not even capable of doing so. And for this very reason the criticism of the personality cult, though rhetorically harsh, was in essence incomplete and confined from the start to well-defined limits. The process of true democratization was nipped in the bud.