Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley, the son of a mercer, was born in Wigan in October, 1609. There is no evidence that the family was of anything but modest standing in the parish. It is frequently assumed that Winstanley attended the local grammar school but no enrolment records for the period are extant. (1)

Winstanley's family was involved in the cloth trade. At the time the town was known as a centre of the woollen and linen manufacture, drawing both on local supplies and imports of linen flax from Ireland. Many of its inhabitants were also becoming involved with new branches of manufacture, especially cotton. (2)

On 19th April 1630, when he was 20 years old, he was apprenticed to Sarah Gater, who ran a cloth business in the London parish of St Michael Cornhill. He took a keen interest in religion and was described as "a good Christian, and a godly man." (3)

By 1638 he was admitted a freeman of the Merchant Taylors' Company and by the following year had established his own household in the parish of St Olave Jewry where he was involved in the business of buying and selling textiles on credit. (4)

In September 1640 Winstanley married the 27-year-old Susan King. She came from a medical family. Her mother was a midwife and her father, William King, was a prominent surgeon, and two of her sisters had married surgeons earlier the same year. (5)

English Civil War

On 4 January 1642, Charles I sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers). His opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) and it was the beginning of the English Civil War. The Roundheads immediately took control of London. (6)

Gerrard Winstanley was a "vigorous supporter of parliament" but the war had a bad impact on his business. Several merchants, including Philip Peake and Matthew Backhouse, were unable to pay money they owed Winstanley. In the autumn of 1643 he vacated his house and shop in London and moved to Cobham. He later wrote: "the burdens of and for the soldiery in the beginning of the war, I was beaten out of both estate and trade, and forced to accept the good-will of friends, crediting of me, to live a country life." (7)

Winstanley explained that he was no longer willing to work in the cloth trade. "For matter of buying and selling, the earth stinks with such unrighteousness, that for my part, though I as bred a tradesman, yet it is so hard a thing to pick out a poor living, that a man shall sooner be cheated of his bread, then get bread by trading among men, if by plain dealing he put trust in any." (8)

Only a small number of those who opposed the king in the English Civil War were committed republicans and few of those who took part in these events would have considered themselves revolutionaries. (9) However, some of those fighting did want to change society. In 1645 John Lilburne, John Wildman, Richard Overton and William Walwyn formed a new political party called the Levellers. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (10)

It has been claimed that the ideas of people like Lilburne, Wildman, Overton and Walwyn, had an impact on Winstanley. It is also believed that another source of inspiration was the work of John Foxe. However, David Petegorsky, has argued that "to search for the sources of Winstanley's theological conceptions would be as futile as to attempt to identify the streams that have contributed to the bucket of water one has drawn from the sea." (11)

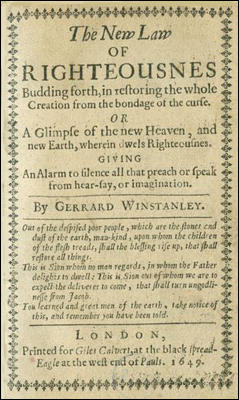

The New Law of Righteousness

During the war life was hard for people living in Cobham. Most people living in the village were landless labourers and the area was dominated by a few entrepreneurial yeomen farmers and gentry. Winstanley was one of the more prosperous farmers but he had sympathy for the poor. On 10th April 1646 Winstanley, with five other men and two women, was fined at Cobham manorial court for digging on waste land and taking peat and turf. According to J. D. Alsop "this was probably a symbolic protest by manorial tenants, four of whom were local office holders". (12)

Winstanley published four pamphlets in 1648. These were highly critical of religious leaders who "hold forth God and Christ to be at a distance from men" or think that "God is in the Heavens above the skies". Winstanley argued that God is "the spirit within you". Winstanley then went on to describe God "doth not preserve one creature and destroy another... but he hath a regard to the whole creation; and knits every creature together into oneness; making every creature to be an upholder of his fellow; and so every one is an assistant to preserve the whole." (13)

In October 1648 Winstanley's friend William Everard was arrested. It was reported that he held blasphemous opinions "as to deny God, and Christ, and Scriptures, and prayer". (14) His arrest prompted Winstanley to publish Truth Lifting up the Head above Scandals (1648), in which he asked who has the authority to restrain religious differences? He argued that Scripture, on which traditionally authority rested, was unsafe because there were no undisputed texts, translations, or interpretations. Winstanley concluded that authority should be based in the spirit. "All people carried the spirit, and thus their own authority, within them. The academics and clergy were following their own imaginations rather than the spirit and... must be seen as false prophets". (15)

Gerrard Winstanley gradually became more radical and he began arguing that all land belonged to the community rather than to separate individuals. In January, 1649, he published the The New Law of Righteousness. In the pamphlet he wrote: "In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." (16)

Winstanley claimed that the scriptures threatened "misery to rich men" and that they "shall be turned out of all, and their riches given to a people that will bring forth better fruit, and such as they have oppressed shall inherit the land." He did not only blame the wealthy for this situation. As John Gurney has pointed out, Winstanley argued: "The poor should not just be seen as an object of pity, for the part they played in upholding the curse had also to be addressed. Private property, and the poverty, inequality and exploitation attendant upon it, was, like the corruption of religion, kept in being not only by the rich but also by those who worked for them." (17)

Winstanley claimed that God would punish the poor if they did not take action: "Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men, your oppressors by your labours... If you labour the earth, and work for others that live at ease, and follows the ways of the flesh by your labours, eating the bread which you get by the sweat of your brows, not their own. Know this, that the hand of the Lord shall break out upon such hireling labourer, and you shall perish with the covetous rich man." (18)

Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them. (19)

The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". (20) Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. These men became known as Diggers. (21)

John Gurney has argued that "Everard's flamboyant character and his preference for confrontation over presentation helped to ensure that in the early days of the digging he was more quickly noticed than the more self-effacing Winstanley, and many observers assumed that it was he, rather than Winstanley, who was the real leader of the Diggers". (22)

According to Peter Ackroyd, Everard proclaimed in a vision by God to "dig and plough the land" and that the Diggers believed in a form of "agrarian communism" and that that it was time for the English to free themselves from the the tyranny of Norman landlords and to make "the earth a common treasury for all." (23)

Laurence Clarkson claimed that he had supported the ideas of Winstanley and had spent some time digging on the commons. However, Winstanley strongly disapproved of Clarkson's sexual ideas and condemned the "Ranting crew" and he warned fellow Diggers to steer clear of "lust of the flesh" and "the practise of Ranting". (24)

Winstanley announced his intentions in a manifesto entitled The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649). It opened with the words: "In the beginning of time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds, and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, that one branch of mankind should rule over another." (25)

Winstanley argued for a society without money or wages: "The earth is to be planted and the fruits reaped and carried into barns and storehouses by the assistance of every family. And if any man or family want corn or other provision, they may go to the storehouses and fetch without money. If they want a horse to ride, go into the fields in summer, or to the common stables in winter, and receive one from the keepers, and when your journey is performed, bring him where you had him, without money." (26)

Digger groups also took over land in Kent (Cox Hill), Buckinghamshire (Iver) and Northamptonshire (Wellingborough). A. L. Morton has argued that Winstanley and his followers used the argument that William the Conqueror had "turned the English out of their birthrights; and compelled them for necessity to be servants to him and to his Norman soldiers." Winstanley responded to this situation by advocating what Morton describes as "primitive communism". (27)

Winstanley's writings suggested that he shared the view held by the Anabaptists that all institutions were by their nature corrupt: "nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use". To prevent power corrupting individuals he advocated that all officials should be elected every year. "When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory." (28)

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." (29) Oliver Cromwell also condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (30)

On 16th April 1649, Henry Saunders, a yeoman of the parish, complained to the council of state about the growing number of Diggers, now "between 20 and 30". A report was sent to General Thomas Fairfax, the commander of the army, stating that "although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seem very ridiculous, yet that conflux of people may be a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow to this disturbance of the peace and quiet of the Commonwealth." It suggested that Fairfax should send some troops to disperse the Diggers and prevent them from returning to St George's Hill. (31)

General Fairfax sent Captain John Gladman was sent to St George's Hill and found only four men digging. The camp had already been dealt with by local inhabitants: "They have digged in all about an acre of land, but it is trampled down by the country people, who would not suffer them to dig one day more." (32)

On 20th April, Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, appeared before General Fairfax in London. Both men, because of their political beliefs, refused to remove their hats in the presence of the General. Everard told Fairfax that since the Norman Conquest, England had lived under a tyranny. He assured Fairfax that he and his fellows did not intend either to interfere with private property or to destroy enclosures, but that they were merely claiming the commons which were the rightful possession of the poor. The two men made it clear that they intended to cultivate the wastelands in common and to provide sustenance for the distressed." (33)

Gerrard Winstanley wrote to General Fairfax in June 1649 explaining his objectives: "And the truth is, experience shows us, that in this work of Community in the earth, and in the fruits of the earth, is seen plainly a pitched battle between the Lamb and the Dragon, between the Spirit of love, humility and righteousness... and the power of envy, pride, and unrighteousness ... the latter power striving to hold the Creation under slavery, and to lock and hide the glory thereof from man: the former power labouring to deliver Creation from slavery, to unfold the secrets of it to the sons of man, and so to manifest himself to be the great restorer of all things." (34)

Winstanley continued his experiment and on 1st June he published A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, that was signed by 44 people. It stated that while waiting for their first crop yields, they proposed to sell wood from the commons in order to buy food, ploughs, carts, and corn. No threat would be made to private property, but "the promises of reformation and liberation made from the solemn league and covenant through to the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords must be honoured". (35)

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark. (36)

Despite the hostility Winstanley's experiment continued and in January 1650 "having put my arm as far as my strength will go to advance righteousness: I have writ, I have acted, I have peace: and now I must wait to see the spirit do his own work in the hearts of others, and whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph." (37)

On 19th April, 1650, a group of local landowners, including John Platt, Thomas Sutton, William Starr and William Davy, with several hired men, destroyed the Digger community in Cobham: "They set fire to six houses, and burned them down, and burned likewise some of the household stuff... not pitying the cries of many little children, and their frightened mothers.... they kicked a poor man's wife, so that she miscarried her child." (38)

Winstanley returned to farming his own land. The historian, Alfred Leslie Rowse, quoted one source that claimed he had made a "most shameful retreat from George's Hill, with a spirit of pretended universality, to become a real tithe-gather of propriety". Rowse harshly argues that "Winstanley was no better than the rest of the Saints - out of his own ends." (39)

The Law of Freedom

Winstanley's best-known work, The Law of Freedom, was published in February 1652 after twenty months of silence following the collapse of the digging experiments. It appears to have been an attempt to enlist the power and influence of Oliver Cromwell. And now you have the power of the land in your hand, you must do one of these two things. First, either set the land free to the oppressed commoners, who assisted you, and paid the Army their wages; and then you will fulfil the Scriptures and your own engagements, and so take possession of your deserved honour. Or secondly, you must only remove the Conqueror's power out of the King's hand into other men's, maintaining the old laws still."

Winstanley urged Cromwell not to establish a dictatorship: "For you (Cromwell) must either establish Commonwealth's freedom in power, making provision for every one's peace, which is righteousness, or else you must set up Monarchy again. Monarchy is twofold, either for one king to reign or for many to reign by kingly promotion. And if either one king rules or many rule by king's principles, much murmuring, grudges, trouble and quarrels may and will arise among the oppressed people on every gained opportunity." (40)

Marxist writers in the 19th century such as Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky have claimed that in this pamphlet Winstanley had provided a complete framework for a socialist order. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) has pointed out: "Winstanley has an honoured place in the pantheon of the Left as a pioneer communist. In the history of the common people he is also representative of that other minority tradition of popular religious radicalism, which, although it reached a crescendo during the Interregnum, had existed since the Middle Ages and was to continue into modern times. Totally opposed to the established church and also separate from (yet at times overlapping) orthodox puritanism, was a third culture which was lower-class and heretical. At its centre was a belief in the direct relationship between God and man, without the need of any institution or formal rites. Emphasis was on an inner spiritual experience and obedience to the voice of God within each man and woman." (41)

In about 1555 Winstanley became active in the Society of Friends (Quakers), a religious group established by George Fox. It was later claimed by Thomas Tenison, that Winstanley was the true originator of the principles of Quakerism. (42) Lewis H. Berens suggested that the similarities between Winstanley's ideas and those of the Quakers were too great to be wholly coincidental. (43) However, William C. Braithwaite, while accepting the similarities between the ideas of Winstanley and Fox, felt the Digger and the founder of Quakerism were most likely to be "independent products of the peculiar social and spiritual climate of the age." (44)

In 1657 Winstanley was given extra land by his father-in-law, William King. When he heard the news Laurence Clarkson attacked him for "a most shameful retreat from Georges-hill… to become a real Tithe-gatherer of propriety." After the death of his first wife, Susan Winstanley in 1664 he married Elizabeth Stanley. They had a son (baptized Gerrard in 1665) and subsequently a daughter and a second son. In 1667 and 1668 Winstanley served as a churchwarden. (45)

Gerrard Winstanley died on 10th September, 1676.

Primary Sources

(1) Gerrard Winstanley, statement (April, 1649)

The work we are going about is this, to dig up George's Hill and the waste grounds thereabouts, and sow corn, and to eat our bread together by the sweat of our brows.

And the first reason is this, that we may work in righteousness, and lay the foundation of making the earth a common treasury for all, both rich and poor, that everyone that is born in the land may be fed by the earth his mother that brought him forth, according to the reason that rules in the creation.

(2) Gerrard Winstanley, letter to General Thomas Fairfax (June, 1649)

We understand, that our digging upon that Common, is the talk of the whole land; some approving, some disowning. Some are friends, filled with love, and sees the work intends good to the Nation, the peace whereof is that which we seek after. Others are enemies filled with fury, and falsely report of us, that we have intent to fortify ourselves, and afterwards to fight against others, and take away their goods from them, which is a thing we abhor. And many other slanders we rejoice over, because we know ourselves clear, our endeavour being no otherwise, but to improve the Commons, and to cast off that oppression and outward bondage which the Creation groans under, as much as in us lies, and to lift up and preserve the purity thereof.

And the truth is, experience shows us, that in this work of Community in the earth, and in the fruits of the earth, is seen plainly a pitched battle between the Lamb and the Dragon, between the Spirit of love, humility and righteousness ... and the power of envy, pride, and unrighteousness ... the latter power striving to hold the Creation under slavery, and to lock and hide the glory thereof from man: the former power labouring to deliver Creation from slavery, to unfold the secrets of it to the sons of man, and so to manifest himself to be the great restorer of all things.

(3) Gerrard Winstanley, The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649)

In the beginning of time God made the earth... Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another... Landowners either got their land by murder or theft... And thereby man was brought into bondage, and became a greater slave than the beasts of the field were to him.

(4) Gerrard Winstanley, The New Law of Righteousness (1649)

And let all men say what they will, so long as such are rulers as call the land theirs, upholding this particular propriety of mine and thine, the common people shall never have their liberty, nor the land be ever freed from troubles, oppressions, and complainings, by reason whereof the Creator of all things is continually provoked.

The man of the flesh judges it a righteous thing that some men who are cloathed with the objects of the earth, and so called rich men, whether it be got by right or wrong, should be magistrates to rule over the poor; and that the poor should be servants, nay, rather slaves, to the rich. But the spiritual man, which is Christ, doth judge according to the light of equity and reason, that all mankind ought to have a quiet subsistence and freedom to live upon earth; and that there should be no bondman nor beggar in all his holy mountain.

No man shall have any more land than he can labor himself or have others to labor with him in love, working together, and eating bread together, as one of the tribes or families of Israel neither giving nor taking hire.

(5) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

That which is yet waiting on your part to be done is this, to see the oppressor's power to be cast out with his person; and to see that the free possession of the land and liberties be put into the hands of the oppressed commoners of England.

And now you have the power of the land in your hand, you must do one of these two things. First, either set the land free to the oppressed commoners, who assisted you, and paid the Army their wages; and then you will fulfil the Scriptures and your own engagements, and so take possession of your deserved honour. Or secondly, you must only remove the Conqueror's power out of the King's hand into other men's, maintaining the old laws still.

(6) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

Kingly government governs the earth by that cheating art of buying and selling, and thereby becomes a man of contention his hand is against every man, and every man's hand against him. And take this government at the best, it is a diseased government and the very City Babylon, full of confusion, and if it had not a club law to support it there would be no order in it, because it is the covetous and proud will of a conqueror, enslaving the conquered people.

This kingly government is he who beats pruning hooks and ploughs into spears, guns, swords, and instruments of war; that he might take his younger brother's creational birth-right from him, calling the earth his, and not his brother's, unless his brother will hire the earth of him; so that he may live idle and at ease by his brother's labours.

Indeed this government may well be called the government of highwaymen, who hath stolen the earth from the younger brethren by force, and holds it from them by force. He sheds blood not to free the people from oppression, but that he may be king and ruler over an oppressed people....

Commonwealth's government governs the earth without buying and selling and thereby becomes a man of peace, and the restorer of ancient peace and freedom. He makes provision for the oppressed, the weak and the simple, as well as for the rich, the wise and the strong. He beats swords and spears into pruning hooks and ploughs. He makes both elder and younger brother freemen in the earth.

(7) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

When public officers remain long in place of judicature they will degenerate from the bounds of humility, honesty and tender care of brethren, in regard the heart of man is so subject to be overspread with the clouds of covetousness, pride, vain glory. For though at first entrance into places of rule they be of public spirit, seeking the freedom of others as their own; yet continuing long in such a place, where honours and greatness is coming in, they become selfish, seeking themselves and not common freedom; as experience proves it true in these days, according to this common proverb, Great offices in a land and army have changed the disposition of many sweet-spirited men.

And nature tells us that if water stands long it corrupts; whereas running water keeps sweet and is fit for common use. Therefore as the necessity of common preservation moves the people to frame a law, and to choose officers to see the law obeyed, that they may live in peace: so doth the same necessity bid the people, and cries aloud in the ears and eyes of England, to choose new officers and to remove old ones, and to choose state officers every year.

The Commonwealth hereby will be furnished with able and experienced men, fit to govern, which will mightily advance the honour and peace of our land, occasion the more watchful care in the education of children, and in time will make our Commonwealth of England the lily among the nations of the earth.

(8) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

The earth is to be planted and the fruits reaped and carried into barns and storehouses by the assistance of every family. And if any man or family want corn or other provision, they may go to the storehouses and fetch without money. If they want a horse to ride, go into the fields in summer, or to the common stables in winter, and receive one from the keepers, and when your journey is performed, bring him where you had him, without money. If any plant food or victuals, they may either go to the butchers' shops, and receive what they want without money - or else go to the flocks of sheep, or herds of cattle, and take and kill what meat is needful for their families, without buying and selling.

(9) Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom (1652)

For you (Cromwell) must either establish Commonwealth's freedom in power, making provision for every one's peace, which is righteousness, or else you must set up Monarchy again. Monarchy is twofold, either for one king to reign or for many to reign by kingly promotion. And if either one king rules or many rule by king's principles, much murmuring, grudges, trouble and quarrels may and will arise among the oppressed people on every gained opportunity.

(10) John F. C. Harrison, The Common People (1984)

Winstanley has an honoured place in the pantheon of the Left as a pioneer communist. In the history of the common people he is also representative of that other minority tradition of popular religious radicalism, which, although it reached a crescendo during the Interregnum, had existed since the Middle Ages and was to continue into modern times. Totally opposed to the established church and also separate from (yet at times overlapping) orthodox puritanism, was a third culture which was lower-class and heretical. At its centre was a belief in the direct relationship between God and man, without the need of any institution or formal rites. Emphasis was on an inner spiritual experience and obedience to the voice of God within each man and woman. This inner-light religion appeared in many different sects, though the best known and longest lived were the Quakers.

Student Activities

John Lilburne and Parliamentary Reform (Answer Commentary)

The Diggers and Oliver Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Military Tactics in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Portraits of Oliver Cromwell (Answer Commentary)