The Levellers

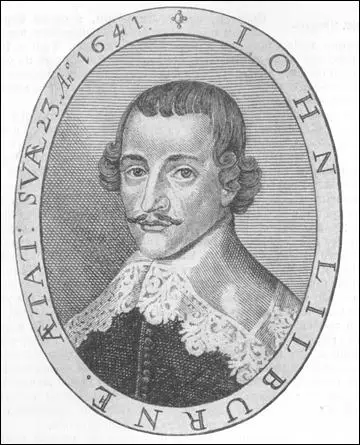

During the English Civil War some radicals began writing and distributing pamphlets on soldiers' rights. Radicals such as John Lilburne were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas he hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position." (1)

William Prynne, a leading Puritan critic of Charles I, became disillusioned with the increase of religious toleration during the war. In December, 1644, he published Truth Triumphing, a pamphlet that promoted church discipline. On 7th January, 1645, Lilburne wrote a letter to Prynne complaining about the intolerance of the Presbyterians and arguing for freedom of speech for the Independents. (2)

John Lilburne and the Levellers

Lilburne's political activities were reported to Parliament. As a result, he was brought before the Committee of Examinations on 17th May, 1645, and warned about his future behaviour. Prynne and other leading Presbyterians, such as his old friend, John Bastwick, were concerned by Lilburne's radicalism. They joined a plot with Denzil Holles against Lilburne. He was arrested and charged with uttering slander against William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons. Lilburne was released without charge on 14th October, 1645. (3)

John Bradshaw now brought Lilburne's case before the Star Chamber. He pointed out that Lilburne was still waiting for most of the pay he should have received while serving in the Parliamentary army. Lilburne was awarded £2,000 in compensation for his sufferings. However, Parliament refused to pay this money and Lilburne was once again arrested. Brought before the House of Lords Lilburne was sentenced to seven years and fined £4,000.

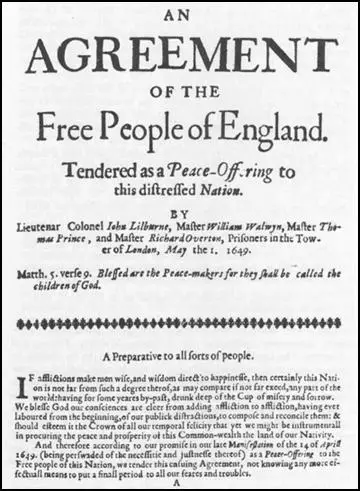

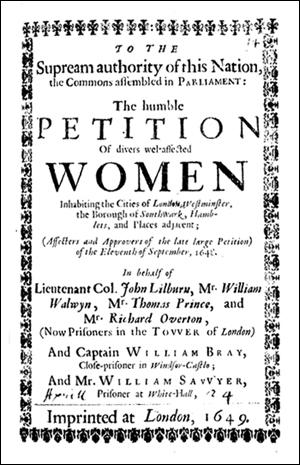

front-cover of a Leveller pamphlet published in 1646.

John Lilburne received support from other radicals. In July, 1646, Richard Overton, launched an attack on Parliament: "We are well assured, yet cannot forget, that the cause of our choosing you to be Parliament men, was to deliver us from all kind of Bondage, and to preserve the Commonwealth in Peace and Happiness: For effecting whereof, we possessed you with the same power that was in ourselves, to have done the same; For we might justly have done it ourselves without you, if we had thought it convenient; choosing you (as persons whom we thought qualified, and faithful) for avoiding some inconveniences." (4)

While in Newgate Prison Lilburne used his time studying books on law and writing pamphlets. This included The Free Man's Freedom Vindicated (1647) where he argued that "no man should be punished or persecuted... for preaching or publishing his opinion on religion". He also outlined his political philosophy: "All and every particular and individual man and woman, that ever breathed in the world, are by nature all equal and alike in their power, dignity, authority and majesty, none of them having (by nature) any authority, dominion or magisterial power one over or above another." (5) In another pamphlet, Rash Oaths (1647), he argued: "Every free man of England, poor as well as rich, should have a vote in choosing those that are to make the law." (6)

In 1647 people like John Lilburne and Richard Overton were described as Levellers. In demonstrations they wore sea-green scarves or ribbons. (7) In September, 1647, William Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (8)

The Levellers gained considerable influence in the New Model Army. In October, 1647, the Levellers published An Agreement of the People. As Barbara Bradford Taft has pointed out: "Under 1000 words overall, the substance of the Agreement was common to all Leveller penmen but the lucid phrasing of four concise articles and the eloquence of the preamble and conclusion leave little doubt that the final draft was Walwyn's work. Inflammatory demands were avoided and the first three articles concerned the redistribution of parliamentary seats, dissolution of the present parliament, and biennial elections. The heart of the Leveller programme was the final article, which enumerated five rights beyond the power of parliament: freedom of religion; freedom from conscription; freedom from questions about conduct during the war unless excepted by parliament; equality before the law; just laws, not destructive to the people's well-being." (9)

The document advocated the granting of votes to all adult males except for those receiving wages. The wage-earning class, although perhaps numbering nearly half the population, were regarded as "servants" of the rich and would be under their influence and would vote for their employer's candidates. "Their exclusion from the franchise was thus regarded as necessary to prevent the employers from having undue influence, and there is reason to think that this judgement was correct." (10)

Colonel Thomas Harrison was sympathetic to the demands of the Levellers and in November, 1648, he began negotiating with John Lilburne. "He attempted to persuade the Levellers that before the agreement could be perfected it was necessary for the army to invade London and prevent parliament from concluding a treaty with the king." He argued that any agreement was likely that the New Model Army. would be disbanded, with the consequence "that you will be destroyed as well as we." (10a).

Lilburne admitted that Harrison was "extremely fair" in the negotiations. "We fully and effectually acquainted

him with the most desperate mischievousness of their attempting to do these things, without giving some good security to the nation for the future settlement of their liberties and freedoms; specially in frequent, free, and successive representations, according to their many promises, oaths, covenants and declarations; or else as soon as they had performed their intentions to destroy the King (which we fully understood they were absolutely resolved to do, yea, as they told us, though they did it by martial law), and also totally to root up the Parliament, and invite so many members to come to them as would join with them, to manage businesses, till a new and equal representative could by an agreement be settled ; which the chiefest of them protested before God was the ultimate and chiefest of their designs and desires... I say, we pressed hard for security, before they attempted those things in the least, lest when they were done we should be solely left to their wills and swords." (10b)

Putney Debates

On 28th October, 1647, members of the New Model Army began to discuss their grievances at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, but moved to the nearby lodgings of Thomas Grosvenor, Quartermaster General of Foot, the following day. This became known as the Putney Debates. The speeches were taken down in shorthand and written up later. As one historian has pointed out: "They are perhaps the nearest we shall ever get to oral history of the seventeenth century and have that spontaneous quality of men speaking their minds about the things they hold dear, not for effect or for posterity, but to achieve immediate ends." (11)

Thomas Rainsborough, the most radical of the officers, argued: "I desire that those that had engaged in it should speak, for really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore truly. Sir, I think it's clear that every man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under; and I am confident that when I have heard the reasons against it, something will be said to answer those reasons, in so much that I should doubt whether he was an Englishman or no that should doubt of these things." (12)

John Wildman supported Rainsborough and dated people's problems to the Norman Conquest: "Our case is to be considered thus, that we have been under slavery. That's acknowledged by all. Our very laws were made by our Conquerors... We are now engaged for our freedom. That's the end of Parliament, to legislate according to the just ends of government, not simply to maintain what is already established. Every person in England hath as clear a right to elect his Representative as the greatest person in England. I conceive that's the undeniable maxim of government: that all government is in the free consent of the people." (13)

Edward Sexby was another who supported the idea of increasing the franchise: "We have engaged in this kingdom and ventured our lives, and it was all for this: to recover our birthrights and privileges as Englishmen - and by the arguments urged there is none. There are many thousands of us soldiers that have ventured our lives; we have had little property in this kingdom as to our estates, yet we had a birthright. But it seems now except a man hath a fixed estate in this kingdom, he hath no right in this kingdom. I wonder we were so much deceived. If we had not a right to the kingdom, we were mere mercenary soldiers. There are many in my condition, that have as good a condition, it may be little estate they have at present, and yet they have as much a right as those two (Cromwell and Ireton) who are their lawgivers, as any in this place. I shall tell you in a word my resolution. I am resolved to give my birthright to none. Whatsoever may come in the way, and be thought, I will give it to none. I think the poor and meaner of this kingdom (I speak as in that relation in which we are) have been the means of the preservation of this kingdom." (14)

These ideas were opposed by most of the senior officers in the New Model Army, who represented the interests of property owners. One of them, Henry Ireton, argued: "I think that no person hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom, and indetermining or choosing those that determine what laws we shall be ruled by here - no person hath a right to this, that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom... First, the thing itself (universal suffrage) were dangerous if it were settled to destroy property. But I say that the principle that leads to this is destructive to property; for by the same reason that you will alter this Constitution merely that there's a greater Constitution by nature - by the same reason, by the law of nature, there is a greater liberty to the use of other men's goods which that property bars you." (15)

A compromise was eventually agreed that the vote would be granted to all men except alms-takers and servants and the Putney Debates came to an end on 8th November, 1647. The agreement was never put before the House of Commons. Leaders of the Leveller movement, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and John Wildman, were arrested and their pamphlets were burnt in public. (16)

Parliament and the Levellers

On 1st August, 1648, the House of Commons voted for Lilburne's release. The next day the House of Lords agreed and also remitted the fine imposed two years earlier. On his release Lilburne became involved in writing and distributing pamphlets on soldiers' rights. He pointed out that even though soldiers were fighting for Parliament, very few of them were allowed to vote for it. Lilburne argued that elections should take place every year. Lilburne, who believed that people were corrupted by power, argued that no members of the House of Commons should be allowed to serve for more than one year at a time.

The House of Commons was angry with Thomas Rainsborough for his support of democracy in the Putney Debates and General Thomas Fairfax was called before Parliament to answer for his behaviour. For a time Rainsborough was denied the right to take up his post as Vice Admiral. Eventually, after support from Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton, Parliament voted 88 to 66 in favour of him going to sea.

As a supporter of the Levellers, Rainsborough was unpopular with his officers and he was refused permission to board his ship. Parliament now appointed the Earl of Warwick as Lord High Admiral and Rainsborough returned to the army. On 29th October, 1648, a party of Cavaliers attempted to kidnap Rainsborough while he was in Doncaster. During the struggle to capture him he was mortally wounded. At his funeral in London the crowd wore sea-green scarves and ribbons. (17)

Oliver Cromwell made it very clear that he very much opposed to the idea that more people should be allowed to vote in elections and that the Levellers posed a serious threat to the upper classes: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (18)

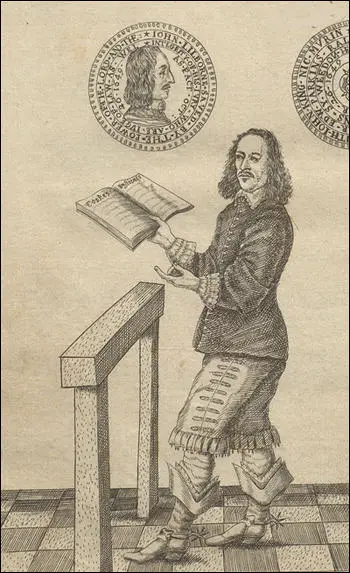

In July, 1648, the Levellers published their own newspaper, The Moderate. Edited by Richard Overton it included articles by John Lilburne, John Wildman and William Walwyn. The articles written by Overton were more radical than contemporary writings by other Leveller leaders. Whereas radicals like Lilburne opposed the trial and execution of the Charles I, for example, Overton supported it as necessary for securing English liberties. (19)

The newspaper controversially encouraged soldiers in the New Model Army to revolt. In March 1649, Lilburne, Wildman, Overton and Walwyn were arrested and charged with advocating communism. After being brought before the Council of State they were sent to the Tower of London. (20)

Riots and protests broke out in London where the Levellers had a strong following. Ten thousand signatures were collected in a few days to a petition demanding the release of John Lilburne. This was soon followed by a second petition signed and presented entirely by women. There were also disturbances in the army and it was decided to send the most disgruntled regiments to Ireland. (21)

A petition of well over 8,000 signatures, calling for Lilburne to be released, was presented to the House of Commons. Sir John Maynard, the MP for Totnes, led the campaign to have Lilburne set free. Maynard was a great supporter of religious freedom and Lilburne described him as a "true friend and faithful and courageous fellow-sufferer" for his beliefs. Maynard told fellow members about "what this brave invincible Spirit hath suffered and done for you." As a result of the debate in August, 1648, the House of Lords cancelled Lilburne's sentence. (22)

New Model Army

Soldiers continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed.

Lockyer's funeral on Sunday 29th April, 1649, proved to be a dramatic reminder of the strength of the Leveller organization in London. "Starting from Smithfield in the afternoon, the procession wound slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the interment in New Churchyard. Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons - black for mourning and sea-green to publicize their Leveller allegiance. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous autumn." (23)

John Lilburne continued to campaign against the rule of Oliver Cromwell. According to a Royalist newspaper at the time: "He (Cromwell) and the Levellers can as soon combine as fire and water... The Levellers aim being at pure democracy.... and the design of Cromwell and his grandees for an oligarchy in the hands of himself." (24)

Lilburne argued that Cromwell's government was mounting a propaganda campaign against the Levellers and to prevent them from replying their writings were censored: "To prevent the opportunity to lay open their treacheries and hypocrisies... the stop the press... They blast us with all the scandals and false reports their wit or malice could invent against us... By these arts are they now fastened in their powers." (25)

David Petegorsky, the author of Left-Wing Democracy in the English Civil War (1940) has pointed out: "The Levellers clearly saw, that equality must replace privilege as the dominant theme of social relationships; for a State that is divided into rich and poor, or a system that excludes certain classes from privileges it confers on others, violates that equality to which every individual has a natural claim." (26)

Although he agreed with some of the Leveller's policies, including the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, Cromwell refused to increase the number of people who could vote in elections. Lilburne attacked Cromwell's suppression of Roman Catholics in Ireland and Parliament's persecution of Royalists in England and the decision to execute Charles I.

In February, 1649, John Lilburne published England's New Chains Discovered. "He appealed to the army and the provinces as well as Londoners to join him in rejecting the rule of the military junta, the council of state, and their ‘puppet’ parliament. Leveller agitation, inspired by his example, revived. He was soon in the Tower again for the suspected authorship of a book which parliament had declared treasonable". (27)

In another pamphlet Lilburne described Cromwell as the "new King." On 24th March, Lilburne read his latest pamphlet, out loud to a crowd outside Winchester House, where he was living at the time, and then presented it to the House of Commons later that same day. It was condemned as "false, scandalous, and reproachful" as well as "highly seditious" and on 28th March he was arrested at his home. (28)

Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince, were also taken into custody and all were brought before the Council of State in the afternoon. Lilburne later claimed that while he was being held prisoner in an adjacent room, he heard Cromwell thumping his fist upon the Council table and shouting that the only "way to deal with these men is to break them in pieces … if you do not break them, they will break you!" (29)

In March, 1649, Lilburne, Overton and Prince, published, England's New Chains Discovered. They attacked the government of Oliver Cromwell pointed out that: "They may talk of freedom, but what freedom indeed is there so long as they stop the Press, which is indeed and hath been so accounted in all free Nations, the most essential part thereof.. What freedom is there left, when honest and worthy Soldiers are sentenced and enforced to ride the horse with their faces reverst, and their swords broken over their heads for but petitioning and presenting a letter in justification of their liberty therein?" (30)

The supporters of the Leveller movement called for the release of Lilburne. This included Britain's first ever all-women petition, that was supported by over 10,000 signatures. This group, led by Elizabeth Lilburne, Mary Overton and Katherine Chidley, presented the petition to the House of Commons on 25th April, 1649. (31) They justified their political activity on the basis of "our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportionable share in the freedoms of this commonwealth". (32)

MPs reacted intolerantly, telling the women that "it was not for women to petition; they might stay home and wash their dishes... you are desired to go home, and look after your own business, and meddle with your housewifery". One woman replied: "Sir, we have scarce any dishes left us to wash, and those we have not sure to keep." When another MP said it was strange for women to petition Parliament one replied: "It was strange that you cut off the King's head, yet I suppose you will justify it." (33)

The following month Elizabeth Lilburne produced another petition: "That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House. Have we not an equal interest with the men of this nation in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and other the good laws of the land? Are any of our lives, limbs, liberties, or goods to be taken from us more than from men, but by due process of law and conviction of twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood? Would you have us keep at home in our houses, when men of such faithfulness and integrity as the four prisoners, our friends in the Tower, are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by soldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children, and families?" (34)

In May 1649 another Leveller-inspired mutiny broke out at Salisbury. Led by Captain William Thompson, they were defeated by a large army at Burford led by Major Thomas Harrison. Thompson escaped only to be killed a few days later near the Diggers community at Wellingborough. After being imprisoned in Burford Church with the other mutineers, three other leaders, "Private Church, Corporal Perkins and Cornett Thompson", were executed by Cromwell's forces in the churchyard. (35) John Lilburne responded by describing Harrison as a "hypocrite" for his initial encouragement of the Levellers. (36)

On 24th October, 1649, Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne was charged with high treason. The trial began the following day. The prosecution read out extracts from Lilburne's pamphlets but the jury was not convinced and he was found not guilty. There were great celebrations outside the court and his acquittal was marked with bonfires. A medal was struck in his honour, inscribed with the words: "John Lilburne saved by the power of the Lord and the integrity of the jury who are judge of law as well of fact". On 8th November, all four men were released. (37)

For a time Lilburne withdrew from politics and made a living as a soap-boiler. However, in 1650 he joined with John Wildman in acting for the tenants of the manor of Epworth on the Isle of Axholme, who had a long-standing claim as fenmen to common lands. His enemies have characterized the episode as part of an attempt by him to spread Leveller doctrines. He was arrested and sent into exile. When he attempted to return in June, 1653, he was arrested and sent to Newgate Prison. (38)

Although once again he was found not guilty of treason. Cromwell refused to release him. On 16th March, 1654, Lilburne was transferred to Elizabeth Castle, Guernsey. Colonel Robert Gibbon, the governor of the island, later complained that Lilburne gave him more trouble than "ten cavaliers". In October, 1655, he was moved to Dover Castle. While he was in prison Lilburne continued writing pamphlets including one that explained why he had joined the Quakers.

In 1655, three veteran Levellers, Edward Sexby, John Wildman and Richard Overton developed a plot to overthrow the government. The conspiracy was discovered and Sexby fled to Amsterdam. It was later discovered that Overton was by this time acting as a double agent and had informed the authorities of the plot. (39)

In May 1657 Sexby published, under a pseudonym, Killing No Murder, a pamphlet that attempted to justify the assassination of Oliver Cromwell. Sexby accused Cromwell of the enslavement of the English people and argued for that reason he deserved to die. After his death "religion would be restored" and "liberty asserted". He hoped "that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest". The following month Edward Sexby arrived in England to carry out the deed, however, he was arrested on 24th July. He remained in the Tower of London until his death on 13th January 1658. (40)

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Overton, A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens (July, 1646)

We are well assured, yet cannot forget, that the cause of our choosing you to be Parliament men, was to deliver us from all kind of Bondage, and to preserve the Commonwealth in Peace and Happiness: For effecting whereof, we possessed you with the same power that was in ourselves, to have done the same; For we might justly have done it ourselves without you, if we had thought it convenient; choosing you [as persons whom we thought qualified, and faithful) for avoiding some inconveniences.

But you are to remember, this was only of us but a power of trust, (which is ever revocable, and cannot be otherwise) and to be employed to no other end, then our own well-being: Nor did we choose you to continue our trust's longer, then the known established constitution of this Commonwealth will justly permit, and that could be but for one year at the most: for by our law, a Parliament is to be called once every year, and oftener (if need be,) as you well know. We are your principals, and you our agents; it is a truth which you cannot but acknowledge: For if you or any other shall assume, or exercise any power, that is not derived from our trust and choice thereunto, that power is no less then usurpation and an oppression, from which wee expect to be freed, in whom so ever we find it; it being altogether inconsistent with the nature of just freedom, which you also very well understand.

(2) Richard Overton, An Arrow Against All Tyrants (October, 1646)

To every individual in nature is given an individual property by nature not to be invaded or usurped by any. For every one, as he is himself, so he has a self-propriety, else could he not be himself; and of this no second may presume to deprive any of without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature and of the rules of equity and justice between man and man. Mine and thine cannot be, except this be. No man has power over my rights and liberties, and I over no man's. I may be but an individual, enjoy my self and my self-propriety and may right myself no more than my self, or presume any further; if I do, I am an encroacher and an invader upon another man's right - to which I have no right. For by natural birth all men are equally and alike born to like propriety, liberty and freedom; and as we are delivered of God by the hand of nature into this world, every one with a natural, innate freedom and propriety - as it were writ in the table of every man's heart, never to be obliterated - even so are we to live, everyone equally and alike to enjoy his birthright and privilege; even all whereof God by nature has made him free.

And this by nature everyone's desire aims at and requires; for no man naturally would be be fooled of his liberty by his neighbour's craft or enslaved by his neighbour's might. For it is nature's instinct to preserve itself from all things hurtful and obnoxious; and this in nature is granted of all to be most reasonable, equal and just: not to be rooted out of the kind, even of equal duration with the creature. And from this fountain or root all just human powers take their original — not immediately from God (as kings usually plead their prerogative) but immediately by the hand of nature, as from the represented to the representers. For originally God has implanted them in the creature, and from the creature those powers immediately proceed and no further. And no more may be communicated than stands for the better being, weal, or safety thereof. And this is man's prerogative and no further; so much and no more may be given or received thereof: even so much as is conducent to a better being, more safety and freedom, and no more. He that gives more, sins against his own flesh; and he that takes more is thief and robber to his kind - every man by nature being a king, priest and prophet in his own natural circuit and compass, whereof no second may partake but by deputation, commission, and free consent from him whose natural right and freedom it is.

(3) John Lilburne, Leveller pamphlet (March, 1647)

No man should be punished or persecuted... for preaching or publishing his opinion on religion.

(4) John Lilburne, The Free Man's Freedom Vindicated (1647)

All and every particular and individual man and woman, that ever breathed in the world, are by nature all equal and alike in their power, dignity, authority and majesty, none of them having (by nature) any authority, dominion or magisterial power one over or above another.

(5) John Lilburne, Rash Oaths (1647)

Every free man of England, poor as well as rich, should have a vote in choosing those that are to make the law.

(6) Major John Wildman was a soldier who took part in the Putney Debates (October, 1647)

Our laws were made by our Norman conquerors... therefore there is no credit to be given to any of them... Every person in England hath as clear a right to elect his own representative as the greatest person in England.

(7) Letter sent by John Lilburne to supporters of the Leveller movement in Kent (1648)

This is the method we have used in London. We have appointed several men in every ward to form a committee... they arrange for the Petition (list of policies supported by the Levellers) to be read at meetings and to take subscriptions.

(8) The Moderate reported in May 1649 on the execution of mutineers at Burford.

This day James Thompson was brought into the churchyard. Death was a great terror to him, as unto most. Some say he had hopes of a pardon, and therefore delivered something reflecting upon the legality of his engagement, and the just hand of God upon him; but if he had, they failed him. Corporal Perkins was the next; the place of death, and sight of his executioners, was so far from altering his countenance, or daunting his spirit, that he seemed to smile upon both, and account it a great mercy that he was to die for this quarrel, and casting his eyes up to His Father and afterwards to his fellow prisoners (who stood upon the church leads to see the execution) set his back against the wall, and bid the executioners shoot; and so died as gallantly, as he lived religiously. After him Master John Church was brought to the stake, he was as much supported by God, in this great agony, as the latter; for after he had pulled off his doublet, he stretched out his arms, and bid the soldiers do their duties, looking them in the face, till they gave fire upon him, without the least kind of fear or terror. Thus was death, the end of his present joy, and beginning of his future eternal felicity. Henry Denne was brought to the place of execution, he said, he was more worthy of death than life and showed himself somewhat penitent, for being an occasion of this engagement; but though he said this to save his life, yet the two last executed, would not have said it, though they were sure thereby to gain their pardon.

(9) John Lilburne, Richard Overton and Thomas Prince, England's New Chains Discovered (March, 1649)

If our hearts were not over-charged with the sense of the present miseries and approaching dangers of the Nation, your small regard to our late serious apprehensions, would have kept us silent; but the misery, danger, and bondage threatened is so great, imminent, and apparent that whilst we have breath, and are not violently restrained, we cannot but speak, and even cry aloud, until you hear us, or God be pleased otherwise to relieve us.

Removing the King, the taking away the House of Lords, the overawing the House, and reducing it to that pass, that it is become but the Channel, through which is conveyed all the Decrees and Determinations of a private Council of some few Officers, the erecting of their Court of Justice, and their Council of State, The Voting of the People of Supreme Power, and this House the Supreme Authority: all these particulars, (though many of them in order to good ends, have been desired by well-affected people) are yet become, (as they have managed them) of sole conducement to their ends and intents, either by removing such as stood in the way between them and power, wealth or command of the Commonwealth; or by actually possessing and investing them in the same.

They may talk of freedom, but what freedom indeed is there so long as they stop the Press, which is indeed and hath been so accounted in all free Nations, the most essential part thereof, employing an Apostate Judas for executioner therein who hath been twice burnt in the hand a wretched fellow, that even the Bishops and Star Chamber would have shamed to own. What freedom is there left, when honest and worthy Soldiers are sentenced and enforced to ride the horse with their faces reverst, and their swords broken over their heads for but petitioning and presenting a letter in justification of their liberty therein? If this be not a new way of breaking the spirits of the English, which Strafford and Canterbury never dreamt of, we know no difference of things.

(10) William Walwyn, Just Defence (1649)

In the year 1646, whilst the army was victorious abroad, through the union and concurrence of conscientious people, of all judgments, and opinions in religion there brake forth here about London a spirit of persecution; whereby private meetings were molested, & divers pastors of congregations imprisoned, & all threatened; Mr. Edwards, and others, fell foul upon them, slander upon slander, to make them odious, and so to fit them for destruction, whether by pretence of law, or open violence he seemed not to regard; and amongst the rest, abused me, which drew from me a whisper in his ear, and some other discourses, tending to my own vindication, and the defence of all conscientious people: and for which I had then much respect from these very men, that now asperse me themselves, with the very same, and some other like aspirations, as he then did.

Persecution increased in all quarters of the land, sad stories coming daily from all parts, which at length were by divers of the Churches. Myself, and other friends, drawn into a large petition; which I profess was so lamentable, considering the time, that I could hardly read it with out tears: and though most of those that are called Anabaptists and Brownists congregations, were for the presenting of it; yet Master Good wins people, and some other of the Independent Churches being against the season, it was never delivered.

(11) Oliver Cromwell commenting on the activities of the Levellers and the Diggers (1649)

What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces.

(12) Elizabeth Lilburne, A Petition of Women (5th May, 1649)

That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House. Have we not an equal interest with the men of this nation in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and other the good laws of the land? Are any of our lives, limbs, liberties, or goods to be taken from us more than from men, but by due process of law and conviction of twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood? And can you imagine us to be so sottish or stupid as not to perceive, or not to be sensible when daily those strong defences of our peace and welfare are broken down and trod underfoot by force and arbitrary power?

Would you have us keep at home in our houses, when men of such faithfulness and integrity as the four prisoners, our friends in the Tower, are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by soldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children, and families? Are not our husbands, our selves, our daughters and families, by the same rule as liable to the like unjust cruelties as they?

Nay, shall such valiant, religious men as Mr. Robert Lockyer be liable to court martial, and to be judged by his adversaries, and most inhumanly shot to death? Shall the blood of war be shed in time of peace? Doth not the word of God expressly condemn it? And are we Christians, and shall we sit still and keep at home, while such men as have borne continual testimony against the injustice of all times and unrighteousness of men, be picked out and be delivered up to the slaughter? And yet must we show no sense of their sufferings, no tenderness of affection, no bowels of compassion, nor bear any testimony against so abominable cruelty and injustice?

(13) Bulstrode Whitelock, Memorials of English Affairs (c. 1660)

The Women Petitioners again attended at the door of the House for an answer to their Petition concerning Lilburne and the rest. The House sent them this answer by the Sergeant: 'That the Matter they petitioned about was of an higher concernment than they understood, that the House gave an answer to their husbands, and therefore desired them to go home, and look after their own business, and meddle with their housewifery.

(14) Lucy Hutchinson, The English Civil War (c. 1670)

These good-hearted people wanted justice for the poor as well as the mighty... for this they were nicknamed the Levellers... these men were just and honest.

(15) On 5 May 1649, a group of women sent a petition to the House of Commons.

Since we are created in the image of God... equal with men... we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so bad in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to be represented in the House of Commons.

(16) John Lilburne, Richard Overton and William Walwyn, Preamble to the third draft of The Agreement of the People (1st May, 1649)

We, the free People of England, to whom God hath given hearts, means and opportunity to effect the same, do with submission to his wisdom, in his name, and desiring the equity thereof may be to his praise and glory; Agree to ascertain our Government to abolish all arbitrary Power, and to set bounds and limits - both to our Supreme, and all Subordinate Authority, and remove all known Grievances. And accordingly do declare and publish to all the world, that we are agreed as followeth.

That the Supreme Authority of England and the Territories therewith incorporate, shall be and reside henceforth in a Representative of the people consisting of four hundred persons, but no more; in the choice of whom (according to natural right) all men of the age of one and twenty years and upwards (not being servants, or receiving alms, or having served the late King in Arms or voluntary Contributions), shall have their votes.

(17) Gerrard Winstanley, The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649)

In the beginning of time God made the earth... Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another... Landowners either got their land by murder or theft... And thereby man was brought into bondage, and became a greater slave than the beasts of the field were to him.

(18) Edward Sexby, Killing No Murder (1657)

To his Highness, Oliver Cromwell. To your Highness justly belongs the Honour of dying for the people, and it cannot choose but be unspeakable consolation to you in the last moments of your life to consider with how much benefit to the world you are like to leave it. 'Tis then only (my Lord) the titles you now usurp, will be truly yours; you will then be indeed the deliverer of your country, and free it from a bondage little inferior to that from which Moses delivered his. You will then be that true reformer which you would be thought. Religion shall be then restored, liberty asserted and Parliaments have those privileges they have fought for. We shall then hope that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest; and we shall then hope men will keep oaths again, and not have the necessity of being false and perfidious to preserve themselves, and be like their rulers. All this we hope from your Highness's happy expiration, who are the true father of your country; for while you live we can call nothing ours, and it is from your death that we hope for our inheritances. Let this consideration arm and fortify your Highness's mind against the fears of death and the terrors of your evil conscience, that the good you will do by your death will something balance the evils of your life.

(19) Tony Benn, The Observer (13th May, 2001)

Modern British politics lacks a sense of history, and historians and the media seem to have agreed that our past should not be allowed to influence our thinking about the future. Yet the ideas we have inherited from the past have a tremendous influence on our thinking whether we acknowledge it or not.

On Saturday, in Burford, Oxfordshire, the annual Levellers' Day Celebration takes place and there will be a huge gathering of people organised by the local branch of the Workers Education Association to commemorate three Leveller soldiers - Private Church, Corporal Perkins and Cornett Thompson - who were shot in the churchyard there in 1649 by Oliver Cromwell's forces. Apart from their radicalism, which was unacceptable to Cromwell, they refused to fight in Ireland where Cromwell, effectively head of state following the execution of Charles I earlier that year, was engaged in a campaign that has scarred Anglo-Irish relations ever since.

The English Civil War of the 1640s was fought between a king who believed in the divine right to govern and Parliament which, however limited its popular base, was arguing for democracy and anticipated by 150 years the ideals that emerged during the French and American revolutions. It was partly in an attempt to broaden the appeal of the message that the Levellers' ('they who would level men's estates,' said detractors) movement grew among more radical supporters of Parliament. They ultimately fell out with Cromwell because, although he shared some of their concerns, he regarded them, particularly those in his New Model Army, as a challenge to his authority. They believed in the sovereignty of the people, were passionate in their commitment to religious toleration and succeeded in establishing democratic control of the military, at one stage, through their representatives who became known as Agitators - the political officers of the army.