Katherine Chidley

Katherine Chidley was born in about 1598. In 1616 she married Daniel Chidley, a tailor of Shrewsbury, and in the same year gave birth to their first child, Samuel Chidley. Over the next thirteen years she gave birth to seven more children. In 1626 she and her husband were prosecuted for non-attendance at church. She was also reported for refusing "to come to be churched after childbirth". (1)

As a result of this conflict with the Church the family moved to London and she became a supporter of the Independents. (2) In 1632 Katherine and Daniel became friends with John Lilburne, who had been deeply influenced by the writings of John Foxe. In 1637 Lilburne met John Bastwick, a Puritan preacher who had just had his ears cut off for writing a pamphlet attacking the religious views of the William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Lilburne offered to help Bastwick in his struggle with the Anglican Church. Eventually it was agreed that Lilburne should go to the Netherlands to organise the printing of a book that Bastwick had written. (3)

Katherine Chidley & Religious Toleration

Katherine Chidley, who was now in her early forties, decided she would become a preacher and was active in the Stepney area. It was extremely unusual for women to play this role and it came to the attention of Thomas Edwards, who was based at at St Botolph Church in Aldgate. He strongly disapproved of Puritan groups such as the Anabaptists and Congregationalists and wanted them suppressed. He warned about the growth in radical preachers touring the country, included "all sorts of illiterate, mechanic preachers, yea of women and boy preachers". (4) Bennett pointed out that in the first epistle to Timothy, St Paul had declared roundly that women should not teach, "but to be in silence; if they were baffled by anything they might ask their husbands for elucidation at home." (5)

Childley also began writing religious pamphlets. In November 1640, she published, The Justification of the Independent Churches of Christ. It was an eighty-one-page rejection of the arguments of the London preacher Thomas Edwards for "hierarchical and centralized church government". Edwards was afraid that "religious toleration would undermine the authority of husbands, fathers, and masters over their wives, children, and servants". (6)

Chidley argued that when "God brought his people into the promised land, he commanded them to be separated from the idolaters". Churches did not need pastors or teachers, for "all the Lords people, that are made Kings and Priests to God, have a free voice in the Ordinance of Election, therefore they must freely consent before there can be any Ordination". She went on to suggest that the humblest members of society, were better qualified to create churches than "ill-meaning priests". She concluded by admitting that although she was "a poor woman" she was willing to debate publicly with Edwards on the subject of religious separatism. (7) Katherine Chidley accused Edwards of having turned the pulpit into a cockpit. All this only increased Edwards's reputation as an opponent of toleration. (8)

On 4th January 1642, Charles I sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London and formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers). His opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) and it was the beginning of the English Civil War. (9)

Brian Manning, the author of The Crisis of the English Revolution (1992) has argued that the war caused a threat to the patriarchal family. As a result "religious beliefs could cause wives to assert their independence from husbands, children from parents, servants from masters". He uses the example of Katherine Chidley who he quotes questioning the authority of the "unbelieving husband" over the "conscience of his believing wife". (10)

In January 1645 Chidley published A New-Years-Gift to Mr. Thomas Edwards. She argued that it was "most befitting a woman" to answer the attacks by Edwards. The Church of England was, she wrote, not a true but a deformed church, which, by admitting all comers to the sacraments, was guilty of "casting God's holy things to dogs". She rejected the idea that religious toleration would result in "toleration to sin". (11) Christopher Hill has pointed out in The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991) that Chidley made clear that "a husband had no more right to control his wife's conscience than the magistrate had to control his." (12)

Thomas Edwards responded to this pamphlet by describing Katherine Chidley as "a brazen-faced audacious old woman". Ian J. Gentles has pointed out: "Whatever her physical appearance, there is no doubt about her audacity. Not only did she write boldly about religious questions, she was a zealous evangelist." Chidley was active in Stepney before moving in 1647 to Bury St Edmunds, where with her son Samuel Chidley, she established a separatist church. (13)

The Levellers

During this period she began to associate with members of the Levellers. Other members of this group included John Lilburne, Elizabeth Lilburne, Richard Overton, Mary Overton, Thomas Prince, John Wildman and William Walwyn. In September, 1647, Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (14)

In February, 1649, John Lilburne published England's New Chains Discovered. "He appealed to the army and the provinces as well as Londoners to join him in rejecting the rule of the military junta, the council of state, and their ‘puppet’ parliament. Leveller agitation, inspired by his example, revived. He was soon in the Tower again for the suspected authorship of a book which parliament had declared treasonable". (15)

In another pamphlet Lilburne described Cromwell as the "new King." On 24th March, Lilburne read his latest pamphlet, out loud to a crowd outside Winchester House, where he was living at the time, and then presented it to the House of Commons later that same day. It was condemned as "false, scandalous, and reproachful" as well as "highly seditious" and on 28th March he was arrested at his home. (16)

Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince, were also taken into custody and all were brought before the Council of State in the afternoon. Lilburne later claimed that while he was being held prisoner in an adjacent room, he heard Cromwell thumping his fist upon the Council table and shouting that the only "way to deal with these men is to break them in pieces … if you do not break them, they will break you!" (17)

In March, 1649, Lilburne, Overton and Prince, published, England's New Chains Discovered. They attacked the government of Oliver Cromwell pointed out that: "They may talk of freedom, but what freedom indeed is there so long as they stop the Press, which is indeed and hath been so accounted in all free Nations, the most essential part thereof.. What freedom is there left, when honest and worthy Soldiers are sentenced and enforced to ride the horse with their faces reverst, and their swords broken over their heads for but petitioning and presenting a letter in justification of their liberty therein?" (18)

All-Women Petition

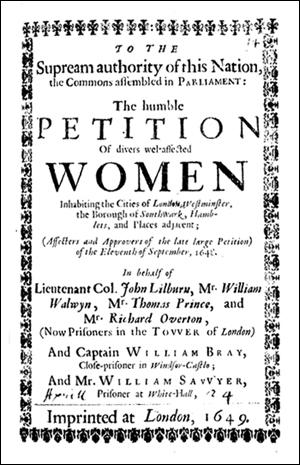

The supporters of the Leveller movement called for the release of Lilburne. Katherine Chidley, Elizabeth Lilburne and Mary Overton organised Britain's first ever all-women petition on the case. This was a difficult task as the mass of women did not question their inferiority and subordination. "Everything suggests that women did indeed regard their sex role as one of dependence and inferiority." (19)

However, women Levellers rejected this view: "The women who preached in public and marched on Parliament with petitions must have been exceptional and forceful members of their sex." (20) They must have been very persuasive as the managed to convince over 10,000 women to sign the petition. This was presented to the House of Commons on 25th April, 1649. (21) They justified their political activity on the basis of "our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportionable share in the freedoms of this commonwealth". (22)

MPs reacted intolerantly, telling the women that "it was not for women to petition; they might stay home and wash their dishes... you are desired to go home, and look after your own business, and meddle with your housewifery". One woman replied: "Sir, we have scarce any dishes left us to wash, and those we have not sure to keep." When another MP said it was strange for women to petition Parliament one replied: "It was strange that you cut off the King's head, yet I suppose you will justify it." (23)

The following month Elizabeth Lilburne produced another petition: "That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House. Have we not an equal interest with the men of this nation in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and other the good laws of the land? Are any of our lives, limbs, liberties, or goods to be taken from us more than from men, but by due process of law and conviction of twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood? Would you have us keep at home in our houses, when men of such faithfulness and integrity as the four prisoners, our friends in the Tower, are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by soldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children, and families?" (24)

Daniel Chidley died in 1649 and Katherine Chidley took over her husband's haberdashery business. She landed at least two substantial contracts to supply 4,000 and 1,000 pairs of stockings to the parliamentary army in Ireland, signing the receipts for her payments in her own hand. Chidley's date of death is unknown and perhaps she died soon after this date.

Primary Sources

(1) Ian J. Gentles, Katherine Chidley : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Shortly after the Long Parliament met in November 1640 the printer William Larner published Katherine Chidley's first tract, The Justification of the Independent Churches of Christ (1641). It was an eighty-one-page riposte to the arguments of the London preacher Thomas Edwards for hierarchical and centralized church government, and a biblical defence of congregational and wifely autonomy....

Churches ought to be exclusive in their membership, she averred, because, "when God brought his people into the promised land, he commanded them to be separated from the idolaters". Churches did not require pastors or teachers, for "all the Lords people, that are made Kings and Priests to God, have a free voice in the Ordinance of Election, therefore they must freely consent before there can be any Ordination". Bitterly she compared the officers of the Church of England to "those Locusts, which ascended out of the bottomless pit" , and denied that any congregation had the power to censure another.