Laurence Clarkson

Laurence Clarkson was born at Preston in 1615. It is believed that he was apprenticed as a tailor in London. On the outbreak of the the English Civil War he joined the Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) as a preacher. During the summer of 1644 he was with the regiment of Colonel Charles Fleetwood. Based in Yarmouth he was paid 20s. a week to preach at local markets. (1)

Clarkson later claimed that he was an extremely popular preacher: "Now after I had continued half a year, more or less the Ministers began to envy me for my doctrine, it being free grace, so contrary to theirs, and that the more as their people came from their own parish to hear me... I continued preaching the Gospel and very zealous I was for obedience to the commands of Christ Jesus." (2)

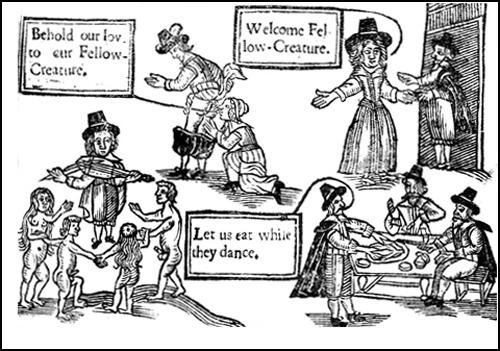

Laurence Clarkson and the Ranters

Clarkson married Frances Marchant in 1645 but soon afterwards there were allegations of sexual impropriety and it was asserted that "we are informed you dipped six Sisters one night naked". (3) Peter Ackroyd claimed that Clarkson professed that "sin had its conception only in imagination" and told his followers that they "might swear, drink, smoke and have sex with impunity". (4)

According to Alfred Leslie Rowse, the author of Reflections on the Puritan Revolution (1986), Clarkson confessed that "a maid of pretty knowledge, who with my doctrine was affected and I affected to lie with her, so that night prevailed and satisfied my lust. Afterwards the maid was highly in love with me, and as gladly would I have been shut of her... not knowing I had a wife, she was in hopes to marry me so would have me lodge with her again." (5)

In October 1647, Clarkson published, A General Charge. It has been claimed that the pamphlet showed his support for the Levellers by defining the "oppressors" as the "nobility and gentry" and the oppressed as the "yeoman farmer" and the "tradesman". (6)

William Lamont has pointed out that in 1648 "Clarkson was retained as 'teacher’ to the company of Captain Owen Cambridge in the horse regiment of Colonel Philip Twisleton, a service for which he was well provided. It is also claimed that during this period he preached to soldiers in Gravesend and Dartford, including Cornet Nicholas Lockyer of Colonel Nathaniel Rich's horse regiment." (7)

The historian, J. C. Davis, claims that during this period he became the leader of a religious group called the Ranters. (8) Clarkson later suggested that it was Abiezer Coppe who was really the leader of this group: "Abiezer Coppe was by himself with a company ranting and swearing, which I was seldom addicted to... Now I being as they said, Captain of the Rant, I had most of the principal women came to my lodging for knowledge... Now in the height of this ranting, I was made still careful for moneys for my wife, only my body was given to other women: so our company increasing, I wanted for nothing that heart could desire, but at last it became a trade so common, that all the froth and scum broke forth into the height of this wickedness, yea began to be a public reproach, that I broke up my quarters, and went into the country to my wife, where I had by the way disciples plenty." (9)

Coppe, a scholar of Oxford University, asserted that property was theft and pride worse than adultery: "I can kiss and hug ladies and love my neighbour's wife as myself without sin." Clarkson agreed with Coppe and supported the idea of "free love" and founded a little group in London called "My One Flesh", a "co-operative of willing maids." (10) Clarkson claimed that "Solomon's writings was the original of my filthy lust". (11)

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Gerrard Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them. (12) The men sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". (13)

Winstanley's supporters became known as Diggers. (14) Laurence Clarkson claimed that he had supported the ideas of Winstanley and had spent some time digging on the commons. Clarkson compared the ideas of Winstanley with those of John Lilburne and the Levellers and described the Diggers as the "True Levellers". (15) However, Winstanley strongly disapproved of Clarkson's sexual ideas and condemned the "Ranting crew" and he warned fellow Diggers to steer clear of "lust of the flesh" and "the practise of Ranting". (16)

Oliver Cromwell and his supporters in the House of Commons attempted to impose a new system of morality. It passed the Adultery Act (May 1650) that imposed the death penalty for adultery and fornication. This was followed by the Blasphemy Act (August 1650). According to Christopher Hill, the author of The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991), this legislation was an attempt to deal with the development of religious groups such as the Ranters. (17)

The Lost Sheep Found

In September 1650 Clarkson published a tract, A Single Eye. As a result he was charged with blasphemy and received a sentence of one-month in prison. Clarkson and Abiezer Coppe, were brought before a parliamentary committee. Clarkson admitting knowing Coppe but claimed "that is all, for I have not seen him above two or three times" (18) It was said that when Coppe appeared he refused to remove his hat in deference. It is claimed he "feigned madness before the investigators" by talking to himself. (19) At other times he flung apples, pears, and nutshells about the room. The committee sent him back to Newgate and decided that there was to be no public trial. (20)

On his release Clarkson returned to his wife, the mother of his five children in Staines. He travelled into Cambridgeshire and Essex where according to one source he eked out an existence performing "white witchcraft". (21)

Laurence Clarkson retained his radical ideas and was upset when Gerrard Winstanley abandoned his political activities and in 1557 accepted land given to him by his prosperous father-in-law, William King. Clarkson attacked him for "a most shameful retreat from Georges-hill… to become a real Tithe-gatherer of propriety." (22)

In 1660 Clarkson published The Lost Sheep Found where he attempted to distance himself from former beliefs. In doing so, Clarkson was the "most revealing" and the" most autobiographical and ingenuously candid" of the Ranters. (23) "As all along in this my travel I was subject to that sin, and yet as saint like, as though sin were a burden to me... concluded there was none could live without sin in this world; for notwithstanding I had great knowledge in the things of God, yet I found my heart was not right to what I pretended, but full of lust and vainglory of this world." (24)

Laurence Clarkson died in a debtors' prison at Ludgate in 1667.

Primary Sources

(1) Laurence Clarkson, The Lost Sheep Found (1660)

Now after I had continued half a year, more or less (as a preacher in Norfolk) the Ministers began to envy me for my doctrine, it being free grace, so contrary to theirs, and that the more as their people came from their own parish to hear me... I continued preaching the Gospel and very zealous I was for obedience to the commands of Christ Jesus; which doctrine of mine converted many of my former friends and others to be baptized, and so into a Church fellowship was gathered to officiate the order of the Apostles, so that really I thought if ever I was in a true happy condition...

I took my journey into the society of those people called Seekers, who worshipped God only by prayer and preaching... As all along in this my travel I was subject to that sin, and yet as saint like, as though sin were a burden to me . . . I concluded there was none could live without sin in this world; for notwithstanding I had great knowledge in the things of God, yet I found my heart was not right to what I pretended, but full of lust and vainglory of this world...

Now after this I returned to my wife in Suffolk, and wholly bent my mind to travel up and down the country, preaching for moneys.... There was few of the clergy able to reach me in doctrine or prayer; yet notwithstanding, not being a University man, I was very often turned out of employment, that truly I speak it, I think there was not any poor soul so tossed in judgement, and for a poor livelihood, as then I was...

I took my progress into the wilderness... with many more words I affirmed that there was no sin, but as man esteemed it sin, and therefore none can be free from sin, till in purity it can be acted as no sin, for I judged that pure to me, which to dark understandings was impure, for to the pure all things, yea all acts were pure...

Abiezer Coppe was by himself with a company ranting and swearing, which I was seldom addicted to, only provine by Scripture the truth of what I acted; and indeed Solomon's writings was the original of my filthy lust, supposing I might take the same liberty as he did, not then understanding his writings was no Scripture, that I was moved to write to the world what my principle was, so brought to public view a book called The Single Eye (October 1650)... men and women came from many parts to see my face, and hear my knowledge in these things, being restless till they were made free, as then we called it. Now I being as they said, Captain of the Rant, I had most of the principal women came to my lodging for knowledge... Now in the height of this ranting, I was made still careful for moneys for my wife, only my body was given to other women: so our company increasing, I wanted for nothing that heart could desire, but at last it became a trade so common, that all the froth and scum broke forth into the height of this wickedness, yea began to be a public reproach, that I broke up my quarters, and went into the country to my wife, where I had by the way disciples plenty...

The ground of this my judgement was, God had made all things good, so nothing evil but as man judged it; for I apprehended there was no such thing as theft, cheat, or a lie, but as man made it so: for if the creature had brought this world into no propriety, as Mine and Thine, there had been no such title as theft, cheat, or a lie; for the prevention hereof Everard and Gerrard Winstanley did dig up the commons, that so all might have to live of themselves, then there had been no need of defrauding, but unity one with another.