Regicides

On 3rd September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died. Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monck, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London.

When Monck arrived he reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monk now contacted Charles II, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s.

This information was passed to Parliament and it was eventually agreed to abolish the Commonwealth and bring back the monarchy. In August 1660, Charles II and Parliament agreed to pass the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion. This resulted in the granting of a free pardon to anyone who had supported the Commonwealth government. However, the king retained the right to punish those people who had participated in the trial and execution of Charles I.

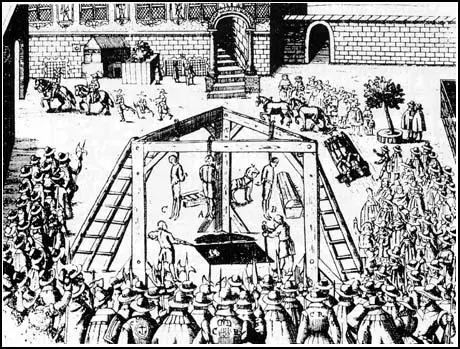

A special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook.

Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves."

Gregory Clement and Adrian Scroop in October 1660.

Samuel Pepys commented that: "I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison, hanged, drawn, and quartered... he looked as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there were great shouts of joy... Harrison's head has been set up (on a pole) on the other side of Westminster Hall." John Evelyn did not see the execution but arrived on the scene soon afterwards: "The traitors executed were Scroop, Cook and Jones. I did not see their execution, but met their quarters mangled and cut and reeking as they were brought from the gallows in baskets."

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and in January 1661 their corpses were exhumed and hung in chains at Tyburn. Three regicides, John Barkstead, John Okey and Miles Corbet were later arrested and were executed in April 1662.

It is estimated that about twenty Regicides escaped abroad. This included Edmund Ludlow who later recorded: "The time appointed for my departure from England being come, after I had settled my affairs in the best manner I could, and taken leave of my dearest friends and relations, I went into a coach about the close of the day, and passing through the City over London-Bridge to St. George's Church in Southwark, I found a person ready to receive me with two horses, one of which I mounted and began my journey.... On the Tuesday following, a small vessel being prepared for my transportation, I went on board; but the wind blowing hard and the vessel having no deck, I removed into another that had been provided for me by a merchant of Lewes, and was struck upon the sands as she was falling down to receive me. This vessel had carried over Mr. Richard Cromwell some weeks before."

Primary Sources

(1) Edmund Ludlow, Memoirs of Edward Ludlow (c. 1680)

Another of my friends who was well acquainted with the designs of the Court, and had all along advised me not to trust their favour; now repeated his persuasions to withdraw out of England, assuring, that if I staid I was lost; and that the same fate attended Sir Henry Vane and others, notwithstanding all engagements to the contrary. He added, that there was a design on foot to seize the estates of all those who had been outlawed in the late King's time, of which number my father having been one, it would be difficult for me to escape ruin on that account. The advice of my friend whom I had always found to be entirely sincere, and knew to be well informed of affairs, was of great weight to induce me to resolve upon departing from England; in which resolution I was confirmed by the friendly counsel of the Lord Ossery, eldest son to the Marquis of Ormond, who with divers others that had observed the inconstancy and irresolution, to say no worse, of those in the House of Commons, in sacrificing Mr. Carew and Colonel Scroop to the revenge of the enemy, concurred in giving the same advice.

The time appointed for my departure from England being come, after I had settled my affairs in the best manner I could, and taken leave of my dearest friends and relations, I went into a coach about the close of the day, and passing through the City over London-Bridge to St. George's Church in Southwark, I found a person ready to receive me with two horses, one of which I mounted and began my journey. My guide was so well acquainted with the country, that we avoided all the considerable towns on the road, where we suspected any soldiers might be quartered ; and the next morning by break of day we arrived at Lewes without interruption. On the Tuesday following, a small vessel being prepared for my transportation, I went on board; but the wind blowing hard and the vessel having no deck, I removed into another that had

been provided for me by a merchant of Lewes, and was struck upon the sands as she was falling down to receive me. This vessel had carried over Mr. Richard Cromwell some weeks before, and lay very commodiously for my safety on that occasion; for after I had entered into her to secure my self from the weather, till I might put to sea in the other, the searchers came on board my small vessel to see what she carried, omitting to search that in which I was, not suspecting any person or thing to be in her, because she was struck upon the sands. But the storm still continuing, and the men thinking not fit to put to sea, we continued in the harbour all that day and the night following; the master, who had used the ports of Ireland whilst I had been in that country, among other things, enquiring if Lieutenant-General Ludlow were not imprisoned with the rest of the King's judges; to which I answered, that I had not heard of any such thing.

The next morning we set sail, and had the wind so favourable, that we arrived in the harbour of Diepe that evening before the gates were shut; where going ashore I was conducted by the master, to the house of one Madame de Caux to whom I was recommended, where I was received with all possible demonstrations of civility; the gentlewoman leaving it to my choice either to continue at her habitation in Diepe, or to go to her house in the country; which last I chose to do, as well that I might enjoy the liberty of taking the air, as to avoid the Irish who were in great numbers in the town, and who probably might have seen me in Ireland when I served the Parliament.

(2) Thomas Harrison, speech on the scaffold (1660)

Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves.

(3) Samuel Pepys, diary entry (13th October, 1660)

I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison, hanged, drawn, and quartered... he looked as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there were great shouts of joy... Harrison's head has been set up (on a pole) on the other side of Westminster Hall.

(4) Mercurius Publicus, newsbook (17th October, 1660)

John Jones chose to marry Oliver Cromwell's sister... and had his hand in the murder of the king. This morning Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Adrian Scroop and John Jones were executed at Charing Cross.... Jones, the last to be executed... lifted up his hands as he was drawn upon the hurdle and at the place of execution... to gain the peoples' prayers.

(5) John Evelyn, diary entry (17 October, 1660)

The traitors executed were Scroop, Cook and Jones. I did not see their execution, but met their quarters mangled and cut and reeking as they were brought from the gallows in baskets.

(6) Edmund Ludlow, Memoirs of Edward Ludlow (c. 1680)

The first letters I received from England, after my arrival at Geneva, informed me that Major-General Harrison, Mr. John Carew, Chief Justice Coke, Mr. Hugh Peters, Mr. Thomas Scot, Mr. Gregory Clement, Colonel Adrian Scroop, Colonel John Jones, Colonel Francis Hacker, and Colonel Daniel Axtel being accused of having contributed in their several stations, to the death of the King, had been condemned and executed. This important business had been delayed during the time that Mr. Love was to continue Sheriff of London, he being no way to be induced, either for fear or hopes, to permit juries to be packed in order to second the designs of the Court. But after new sheriffs had been chosen, more proper to serve the present occasion, a commission for hearing and determining this matter, was directed to thirty-four persons, of whom fifteen had actually engaged for the Parliament, against the late King; either as members of Parliament, judges or officers in their army; most, if not all of them, the Lord Mayor excepted, having been put into places of trust and profit since the late revolution.