Ann Docwra

Anne Waldegrave, he eldest daughter of Sir William Waldegrave of Bures, Suffolk, was born in about 1624. Waldegrave was a justice under King Charles I. When she was about fifteen her father encouraged her to study the law since women "must live under the laws as well as men". (1)

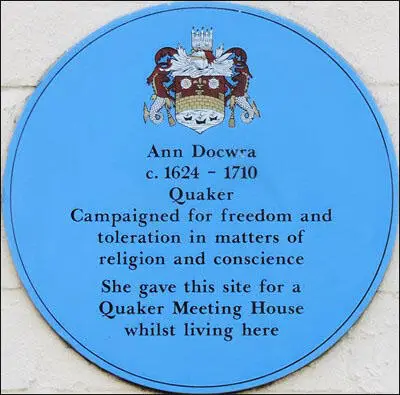

Anne married James Docwra, and both became Quakers. Although they were both royalists and welcomed the return of King Charles II. On her husband's death in 1672 she moved into Cambridge, where she made her home available for Friends' meetings and the accommodation of travelling ministers. (2)

At a meeting in May 1675, Quaker leaders in London, including William Penn, Thomas Salthouse. Alexander Parker and George Whitehead, published a document concerning the role of women in the movement. It stated that all marriages be cleared twice by women's and men's meetings, to make sure that "all foolishand unbridled affections" be speedily brought under God's judgment. It also reminded Quakers that women's meetings, just like men's meetings, had been set up with God's counsel and sharply admonished those who sneered at them as "synods" and "Popish impositions". Violators of these instructions - "disorderly walkers" - should have their names recorded. (3)

It has been claimed by one Quaker historian "Separate men's and women's Business Meetings were recommended at all levels of the structure, each with their own areas of responsibility. Fox argued this was necessary for women to have their own voice, although their areas of influence were highly gendered and limited to pastoral duties such as marriage arrangements and poor relief. It seems that whilst the ideal of spiritual equality persisted, political equality did not." (4)

One of the main opponents of women's meetings was Anne Docwra. In her pamphlet, A looking-glass for the recorder and justices of the peace and grand juries for the town and county of Cambridge (1682) she argued that St Paul had debarred women from having authority over men; women, however, could prophesy and guide men Friends in the administration of charity funds. (5)

In April 1683, Docwra visited George Fox in London to discuss these matters. She had heard from a relative that he was as "big as two or three, and spent his time dozing, in a near stupor from liquor and brandies". Instead she found "a big man, true, taller than average, big boned, his face rounded, a bit on the fat side, but not incapacitated." Anne added "he moved stiffly, and his hands and fingers were so puffy he could not write". However, she left impressed with the way he supported women's meetings. (6)

According to her biographer, Michael Mullett: "Anne Docwra was, apparently, immune from persecution throughout the post-Restoration period, perhaps, as she claimed, as a result of her knowledge of the law and also, probably, because of her rank and background, and maybe in return for the clear royalist standpoint she and some local Friends professed in 1680. " (7)

Anne Docwra died in 1710.

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Mullett, Anne Docwra : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (September, 2004)

Anne Docwra was, apparently, immune from persecution throughout the post-Restoration period, perhaps, as she claimed, as a result of her knowledge of the law and also, probably, because of her rank and background, and maybe in return for the clear royalist standpoint she and some local Friends professed in 1680. In 1687 her Spiritual Community Vindicated amongst People of Different Perswasions in some Things fully supported James II's pursuit of toleration. In 1699, in An Apostate Conscience Exposed, she attacked her nephew, the Quaker renegade Francis Bugg (1640–1727): the work also contains a vivid defence of Fox's simplicity of life against Bugg's charges of luxury against the Quaker leader. In the following year, in The Second Part of an Apostate Conscience Exposed, Docwra countered Bugg's riposte, Jezebel Withstood.

Docwra's enduring gift to Cambridge Friends came in a two-part legacy in 1700 and 1710, in which she gave an estate in Jesus Lane to the society with a 1000 year lease; in her will, dated 4 and 6 May 1710, by now living in reduced circumstances, she made further bequests to several Friends, confirmed her husband's earlier gifts of lands, and added a gift of £20 for a graveyard. She died the same year in Cambridge, where she was buried.

Criticized both by Bugg and by voices of mainstream Quakerism in her day, an individualist difficult to contain within an organization acquiring structural coherence, Anne Docwra was a spirited, intelligent, articulate, educated, and wise lady, one who preferred 'rational argument to visionary insight' (Mack, 316) and who yet held to a deep spiritual sense of the Quaker 'glad tidings of the Light' (ibid., 318).