Martha Simmonds

Martha Calvert was baptized at Meare, Somerset, on 28 January 1624. She was the daughter of George Calvert vicar of Meare, and his second wife, Ann Collier. Martha was the younger sister of the booksellers George and Giles Calvert. Giles's shop at the Black Spread Eagle in St Paul's Churchyard, London, was the leading outlet for the works of early Quakers. (1)

Martha moved to London to live with her brother and was converted to Quakerism in about 1654, and wrote several pamphlets about her new faith, three of which were published by her brother Giles Calvert: When the Lord Jesus Came to Jerusalem (2); A Lamentation for the Lost Sheep of the House of Israel (3); and O England, thy Time is Come (4).

Martha Simmonds: Quaker

In about 1655 she married Thomas Simmonds who had recently returned to London after several years as a bookseller in Birmingham. In March 1655 the Quakers established the Bull and Mouth as their main London meeting place, where Thomas opened his bookshop; he became their principal publisher the following year. During his Birmingham years he had connections with George Calvert. By December 1655 she had been imprisoned several times in Colchester for interrupting church services and walking through the town in sackcloth and ashes. (5)

A group of women including Martha began in 1656 to interrupt Quaker meetings led by Francis Howgill and Edward Burrough, singing and chanting "innocency". The women were condemned by leading Quakers and turned turned to James Nayler for justice. George Whitehead, believed that: "Nayler... came to be ensnared through the subtle Adversary's getting advantage upon him by means of some persons who too much gloried in him... so it came to pass, according as Nayler related to me... that a few forward, conceited, imaginary women, especially one Martha Simmonds, grew somewhat turbulent... that he came to be clouded in his judgement ... The substance of the foregoing relation, how Nayler came to be ensnared and to such a loss, he himself gave me the account." (6)

Some male Quakers considered her a witch. H. Larry Ingle argues that "she was certainly a powerful woman, a fact that helps explain the degree of opposition to her." According to Ingle one of the problems was that like many Quakers "she spoke in a language that could not be read literally but was peppered with metaphors and images that had meaning to her but to few others.... it is easy to see how her enemies - and she had many in and outside the Children of the Light - could consider her a witch." (7)

Bernadette Smith, has attempted to recover Simmonds' reputation in her article The Testimony of Martha Simmonds (2008). Smith argues that male writers have constantly referred to Simmonds as a"'possible witch", a "Ranterish woman". Smith quotes Andrew W. Brink sees Simmonds as the "model for Eve and compares Eve's supposed deception of Adam to Simmonds' part in Nayler's downfall... Simmonds: would not leave him (Nayler) alone in London or in Bristol, following him... much as Satan tracked Eve until he (Satan) implanted the self-destructive idea of becoming a goddess." (8) Margaret Drabble also gets critized as she mentions her only as an adjunct to Nayler and makes no mention of her own writings. (9)

James Nayler

James Nayler arrived in London in July 1655. As soon as he appeared in what he termed "this great and wicked city where abomination is set" he began attracting large numbers to his meetings. He found Baptists and soldiers especially responsive to his message. Nayler was an accomplished speaker and writer, as well as a creative thinker. William Dewsbury, who had the opportunity to watch both Fox and Nayler when they visited Northampton, marveled at the way Nayler "confounded the deceit" of the audience and thought he was a greater speaker than Fox. (10)

Christopher Hill has argued that many people in the movement regarded Nayler as the "chief leader" and the "head Quaker in England". (11) Colonel Thomas Cooper pointed out in the House of Commons: "He (Nayler) writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect." (12) Even one of his critics, John Deacon, conceded that he was "a man of exceeding quick wit and sharp apprehension, enriched with that commendable gift of good oratory with a very delightful melody in his utterance." (13)

According to H. Larry Ingle: "Some people, Friends as well as outsiders, looked on Fox as a bit 'strange' - a word used by a close observer and companion - and wondered at the way other Quakers tended to be quiet in his presence and defer to him during meetings. In personal debate Nayler was quick and intelligent. His writings were incisive and polished, whereas Fox in his writings tended to plod and stumble. if not as charismatic, Nayler still attracted a bevy of followers of an intense type, people who practically worshiped him as the harbinger of a new age. They were willing to follow him anywhere and to do practically anything to demonstrate their commitment. Some of the most vocal of these acolytes were women, and this fact led detractors, then and later, to see an insidious influence at work: either he had some mysterious hold over these women or they themselves were temptress using their wiles to turn his head." (14)

No written rules governed the Society of Friends because it was a kind of community of equals, all committed to the same goals and having the interests of the group at heart. The question of leadership was left open. Fox and Nayler had been involved in the movement together almost from the beginning and shared many days and nights of travelling, and co-authored pamphlets and epistles. However, by 1655 Fox came infrequently to London, preferring to continue his travels in the countryside, and some regarded Nayler as the movement's leader. This was especially true of Martha Simmonds, "an intelligent and independent person, author of several moving pamphlets about spiritual seeking and apocalyptic hopes." (15)

Fox became concerned about how Nayler was winning such a fervent band of disciples in London. It seemed to Fox that Nayler was erecting a base of influence that gave him a strength and a prestige independent of Fox. In the meetings he held he began talking about "wicked mountains and parties crying against him". With the ability to win followers, "Nayler posed a threat of major proportions to Fox. No movement can follow two masters, as Fox realized." (16)

Oliver Cromwell was also becoming concerned about the popularity of Nayler. As Christopher Hill pointed out: "Nayler was a leader of an organized movement which, from its base in the North, had swept with frightening rapidity over the southern counties. It was a movement whose aims were obscure, but which certainly took over many of the aims of the Levellers, and was recruiting former Levellers and Ranters... M.P.s were anxious to finish once and for all with the policy of religious toleration which, in their view, had been the bane of England for a decade. The government of the Protectorate, satisfactorily conservative in many ways, was still in their view woefully unsound in this respect. The fact that its relative tolerance resulted from its dependence on the Army only heightened the offence." (17)

In January 1656, Fox was imprisoned in Launceston. Martha Simmonds travelled to Launceston to meet with Fox, and to state her view that Nayler was the leader of the movement. Fox wrote to Nayler an indignant letter reporting that "she (Simmonds) came singing in my face, inventing words" and informing him that his heart was rotten. In September 1656, Fox was released from prison and proceeded to Exeter, where he demanded that Nayler acknowledge subservience, and when Nayler refused to kiss his hand told him insultingly to kiss his foot instead. (18) They parted bitterly, and later Fox remembered this episode as a critical threat to the movement: "So that after I had been warring with the world, now there was a wicked spirit risen up amongst Friends to war against". (19)

In October 1656, Nayler re-enacted the Palm Sunday arrival of Christ in Jerusalem. Seated on an ass he was escorted into Bristol by women, including Martha Simmonds, strewing branches in his path. Oliver Cromwell and other members of the House of Commons were horrified by Nayler allowing himself to be hailed by devoted disciples as a new Messiah. Nayler was arrested. Philip Skippon, a staunch presbyterian and the major-general in charge of the London area, complained that Cromwell's policy of toleration had fostered a Quaker threat: "Their great growth and increase is too notorious, both in England and Ireland; their principles strike at both ministry and magistracy. Many opinions are in this nation (all contrary to the government) which would join in one to destroy you, if it should please God to deliver the sword into their hands." (20)

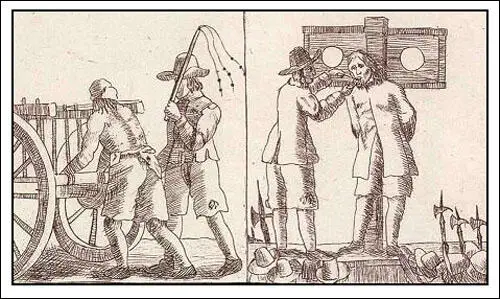

At his trial before Parliament, Nayler declared that he had enacted a "sign" without mistaking himself for Christ. A few members were prepared to accept his account, but the majority were determined on punishment and disagreed only as to its extent. By the narrow margin of 96 to 82, a motion to put him to death was defeated, and after further debate it was resolved on 16 December that Nayler be whipped through the streets by the hangman, exposed in the pillory, have his tongue bored through with a red-hot iron, and have the letter B (for blasphemy) branded on his forehead. He was then to be returned to Bristol and compelled to repeat his ride in reverse while facing the rear of his horse, and finally he was to be committed to solitary confinement in Bridewell Prison for an indefinite period. (21)

Nayler's punishment was carried out in every detail, including 300 lashes that tore all the skin off his back, and the concluding scene at the pillory was witnessed by a large crowd that included Thomas Burton, the MP for Westmorland. He approved of the punishment but admired Nayler's stoicism: "He put out his tongue very willingly, but shrinked a little when the iron came upon his forehead. He was pale when he came out of the pillory, but high-coloured after tongue-boring… Nayler embraced his executioner, and behaved himself very handsomely and patiently." (22) Martha Simmonds, Hannah Stranger and Dorcas Erbury sat at the foot of the pillory in a tableau recalling the three Marys at the foot of the cross. Afterwards Simmonds was arrested. (22a)

Christopher Hill has argued that Oliver Cromwell used the Nayler incident to suppress the Quakers: "So conservatives in Parliament seized the occasion to put the whole Quaker movement in the dock, and the government's religious policy too. The hysteria of M.P.s' contributions to the debate shows how frightened they had been, how delighted they were to seize the opportunity for counterattacked. And the conservatives won their showdown with the government. Nayler was tortured, to discourage the others. Cromwell queried the authority for Parliament's action against Nayler, but ultimately he made political use of the Nayler case to manoeuvre the Army into accepting Parliament's Petition and Advice, a constitution which established something like the traditional monarchy and state church, and drastically limited the area of religious toleration." (23)

Mabel Brailsford has blamed Martha Simmonds for what happened in Bristol and described her as "the villain of this piece", coming into Nayler's life "like a whirlwind... to cause havoc". (24) Kenneth Carroll approaches the Bristol event entirely from Nayler's viewpoint and uses language which precludes any discussion of Simmonds as a political agent but stereotypes her into the same role of dangerous woman, and casts Nayler in the role of victim: "Not even in Bristol was the ailing Nayler safe from Martha Simmonds, for she followed him there in order to bring him under her control." (25)

Martha Simmonds died in Bermondsey, on 27 September 1665.

Primary Sources

(1) Martha Simmonds, O England, thy Time is Come (c.1656)

You foolish virgins, how have you been sleeping away your precious time? had it not been better you had watched and prayed? O foolish, foolish children, will you sell your birthright for a moment's pleasure, and a little ease? But what more can be said to you? I see the Spirit is grieved with you, and the Spirit is weary with striving with you. Oh that I could weep tears of blood for the slackness of the desires of the people concerning their eternal salvation! Is your souls of no more value than to make a sport of time? O England! thou hast not wanted for warnings; my soul stands witness in the presence of the Lord against thee, that in thy cities, towns, and market streets I have passed with bitter cries and streams of tears, for almost two years time, warning you of this day that is coming withupon you as a snare, with this lamentation, O people of England, repent! O that thou wouldst consider the time of thy visitation! O that thou wouldst prize thy time before the door of mercy is shut! Now the light is risen, how art thou found slaying the Lamb of God? In thee is found slain the blood of the innocent; O England! the blood of the innocent cries loud in the ears of the Lord God of power. Oh that thou wouldst consider and repent, and prize thy time before thou be consumed and made a common deluge forever! Thou art fat and full, thou art fitted for slaughter, and great and terrible will thy day of calamity be; the sword of the Lord is drawn against thee and will be sheathed in thy bowels. Oh repent! repent, and let the destruction of Sodom be a warning to thee. O England! fitted for slaughter; thou art light and vain, thou kicks against the Lord, thou lifts up thy heel against him. O England, the time is come that nothing will satisfy but blood; yea, yea the time is come that nothing will satisfy but blood. Thou art making thyself drunken with the blood of the innocent; he will be avenged of thee, till blood come up to the horse's bridle; thou art making thyself drunken with the blood of the innocent, and now he will give thee blood to drink, for thou art worthy; for he will be avenged of thee till he is satisfied with thy blood. Come down ye high and lofty ones and lie in the dust, and repent in sackcloth, and lie low before the Lord, and come and see if by any means there may be a place for repentance found.

This mournful cry began at London, so to Colchester, and through the nation: Ah Lord! what shall I yet say for them? or how shall I enter into a treaty for them? Behold, they have slighted thy tenders of grace, and they wipe their mouths, and take their fills of mirth; and they wipe their mouths and cry, "Tush, the Lord is gone far off." They cry, "Miracles are ceased, and there is no revelation; tush, the Lord seeth not." When thy servants have showed them thy mind, they have said, "Let him do his worst." O Lord, arise in thy zeal, and show thy power, for they blaspheme thy name continually; how have they slighted thy love, now thou hast visited the earth with thy pure voice? How cruelly have they beaten thy prophets, and now thy Son is come they conspire to kill him?

(2) Bernadette Smith, The Testimony of Martha Simmonds (2008)

In December 1656, a newspaper published in detail the account of the dramatic "sign" performed by the Quaker leader, James Nayler and a small group of women. It goes on to describe the examination, the length of time Parliament spent debating his fate, and punishment meted out to him for what were judged to blasphemous utterances and actions. He was to be pilloried and have the letter 'B' branded on his forehead. While he endured his fate, two women were with him, one at either side, reminiscent of the women at the Crucifixion. One of these was the Quaker, Hannah Stranger and the other Martha Simmonds. The incident, which has become known as "the Bristol event" or sign, was the re-enactment of Christ's adventus into Jerusalem, an event I will return to later. Historians and literary critics have traditionally considered Martha Simmonds to be the "ringleader" in this drama. In spite of the fact that she was not alone in this event, her participation in it has defined her from the outset.

Kenneth Carroll, while attempting to render a sympathetic and unbiased account of the Simmonds and Nayler relationship, approaches the Bristol event entirely from Nayler's viewpoint and uses language which precludes any discussion of Simmonds as a political agent but stereotypes her into the same role of dangerous woman, and casts Nayler in the role of victim: "Not even in Bristol was the ailing Nayler safe from Martha Simmonds, for she followed him there in order to bring him under her control."

Martha Simmonds was undoubtedly influential in Nayler's ministry, as he was in hers, but if we look more closely at her life we see that her relationship with him was brief and a critical reading of her texts and letters, and transcripts of her spoken words reveal an articulate and engaging woman with courage and energy.

The American feminist theologian, Rosemary Radford Reuther, is also sympathetic to the women in Nayler's history, but she and Trevett stand alone in their assessment of the female followers of James Nayler and even they offer no analysis of her writings. Reuther's thesis identifies two distinct categories of feminist writers in the midseventeenth century: the 'humanists' and the 'prophets'. Humanists, she argues, are those with access to a classical education, "usually Anglicans" who did not question the status quo of English religious tradition, while the latter group are so called because of their dissenting religious views and their apocalyptic language.

Perhaps the reason for the continued hiddenness of the early Quaker women's writings is the failure of successive generations to question both the structure and nature of theological discourse, which has excluded women. Martha Simmonds has been among this hidden group of women for four centuries and I hope to present her as one of a group of Quaker women who were able to consolidate their mission through the utilisation of, and engagement with, the contemporary cultures of print, religious discourse and apocalyptic preaching which made them unique as a group, if not unprecedented.

(3) Maureen Bell, Martha Simmonds : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2015)

At the time of her conversion Martha Simmonds had been living in London since probably the 1640s (most likely at her brother's shop) and in A Lamentation she describes many years of spiritual seeking. About 1655 she married Thomas Simmons or Simmonds (b. c.1618) who had recently returned to London after several years as a bookseller in Birmingham. In March 1655 the Quakers established the Bull and Mouth as their main London meeting place, where Thomas opened his bookshop; he became their principal publisher the following year. During his Birmingham years he had connections with George Calvert, and Giles Calvert may have supported the London venture as an extension of his own Quaker publishing. Martha, however, soon left London for Essex. By December 1655 she had been imprisoned several times in Colchester for interrupting church services and enacting signs, and walking through the town in sackcloth and ashes.

Martha's part in the events of summer 1656 has been variously interpreted as female hysteria, witchcraft, or a challenge to male Quaker leadership. A group of women including Martha began in 1656 to interrupt Quaker meetings led by Francis Howgill and Edward Burrough, singing and chanting 'innocency'. The women, condemned by Burrough, William Dewsbury, and Richard Hubberthorn, turned to James Nayler for justice. Martha's powerful appeal triggered a spiritual crisis in Nayler, who stayed at her house for three days, an episode leading to accusations by George Fox of witchcraft. In July, Friends tried to part Nayler and Martha forcibly by taking him to Bristol, though George Bishop later denied her account of being thrown downstairs. Nayler proceeded towards Exeter, where shortly afterwards he was imprisoned, while Martha returned to London and offered herself as nurse to Major-General John Desborough's wife, a sister of Cromwell. As reward for her services she obtained an order for Nayler's release which, with her husband and Hannah and John Stranger, she delivered to Exeter in October.