James Nayler

James Nayler was born at West Ardsley, in 1618. He married his wife, Anne, in 1639 and settled in Wakefield, where three daughters were born during the next four years. On the outbreak of the English Civil War he enlisted in the parliamentary army. At first he served as a foot soldier under General Thomas Fairfax. Later he was a quartermaster in the cavalry under General John Lambert, who described him as "a very useful person" and "a man of a very unblameable life and conversation, a member of a very sweet society of an independent church". (1)

Nayler began preaching to the other soldiers. Nayler would have been aware of the teaching of John Lilburne and the Levellers. These men were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas they hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position." (2)

Lilburne's political activities were reported to Parliament. As a result, he was brought before the Committee of Examinations on 17th May, 1645, and warned about his future behaviour. William Prynne and other leading Presbyterians, such as John Bastwick, were concerned by Lilburne's radicalism. They joined a plot with Denzil Holles against Lilburne. He was arrested and charged with uttering slander against William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons. (3)

Nayler insisted he was never a member of the Levellers. (4) At the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 an officer in the New Model Army recalled: "I found it was James Nayler preaching to the people, but with such power and reaching energy as I had not till then been witness of… I was struck with more terror before the preaching of James Nayler than I was before the battle of Dunbar, when we had nothing else to expect but to fall a prey to the swords of our enemies." (5)

James Nayler & George Fox

In 1651 ill health (probably consumption) forced Nayler to leave the army and return home, where he resumed farming and joined the Independent congregation of Christopher Marshall at Woodchurch. Soon afterward he encountered George Fox, who was visiting the area. According to Leo Damrosch, "there is no evidence to support Fox's later suggestion that this meeting was the cause of Nayler's conversion... Certainly radical religious ideas had been widely discussed in the New Model Army, and it may be more than coincidental that Anthony Nutter, whom Fox's family had known in Leicestershire, was the minister at West Ardsley when Nayler was growing up." (6)

Nayler claimed that he was converted while ploughing he heard a voice commanding "Get thee out from thy kindred, and from thy father's house", and after a brief hesitation, during which he fell seriously ill, he left home on impulse for a life of itinerant preaching: "Going gateward with a friend from my own house, having on an old suit, without any money, having neither taken leave of wife or children, not thinking then of any journey, I was commanded to go into the west not knowing whither I should go nor what I was to do there." (7)

It has been argued by Pink Dandelion, the author of The Quakers (2008) that Nayler's experience of war led him to adopt a pacifist approach and to see outward war and fighting as carnal. This view was also held by George Fox who when held in Derby Jail in 1650 he was offered a captaincy in the army in exchange for the freedom but he declined, claiming he fought with spiritual weapons not outward ones. (8)

Nayler met Fox met at Woodchurch in 1651. According to Nayler's biographer, Leo Damrosch, "there is no evidence to support Fox's later suggestion that this meeting was the cause of Nayler's conversion... Certainly radical religious ideas had been widely discussed in the New Model Army, and it may be more than coincidental that Anthony Nutter, whom Fox's family had known in Leicestershire, was the minister at West Ardsley when Nayler was growing up." (9)

Nayler and Fox had similar religious views and both became wandering preachers and became leaders of the group known as "Children of the Light" or "Friends of the Truth". However, their critics described them as "Quakers". This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that the followers of Nayler and Fox quaked and trembled during their worship. Later the group became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (10)

Nayler developed a reputation as "an eloquent preacher and charismatic leader in a movement that explicitly repudiated hierarchy". The Quakers believed that individuals of either sex could receive the same prophetic inspiration that the biblical writers had and, guided by the inner light, could express this with full authority. (11) Nayler wrote: "The true ministry is the gift of Jesus Christ, and needs no addition of human help and learning… and therefore he chouse herdsmen, fishermen, and plowmen, and such like; and he gave them an immediate call, without the leave of man". (12)

Local people were encouraged to harass Nayler and Fox, sometimes stoning and beating them in unruly mobs, and they were arrested at Kirkby Stephen and imprisoned at Appleby, Westmorland until April of 1653. For the rest of that year and throughout 1654 Nayler travelled and preached extensively in the north, winning admiration for the power and cogency of his speaking. (13) Nayler argued that he himself had been a ploughman, and that when the apostles proclaimed the gospel "they were counted fools and madmen by the learned generation". (14)

The Anabaptists, Levellers, the Diggers, and the Ranters were efficiently suppressed. However, the Quakers received help from powerful landowners such as Judge Thomas Fell who was MP for Lancaster and a close ally of Oliver Cromwell. Although he never became a Quaker he was willing to protect them from prosecution. His wife, Margaret Fell, became an important member and Swarthmoor Hall became the headquarters of the movement. (15)

Quakerism

Nayler would often interrupt religious services and accused ministers of being "hireling priests" and demanded abolition of the benefices and tithes that supported them. It was a fixed Quaker principle to accept no payment for preaching and to address any who might listen, often speaking in the open air, rather than to form settled congregations. When ministers complained that unauthorized preachers were invading their territory, Nayler replied, 'It is true, our habitation is with the Lord, and our country is not of this world". (16) Some three dozen Lancashire ministers appeared at Lancaster quarter sessions to lodge a complaint against Nayler and Fox, but Judge Fell interceded on their behalf and they were released. (17)

James Nayler arrived in London in July 1655. As soon as he appeared in what he termed "this great and wicked city where abomination is set" he began attracting large numbers to his meetings. He found Baptists and soldiers especially responsive to his message. Nayler was an accomplished speaker and writer, as well as a creative thinker. William Dewsbury, who had the opportunity to watch both Fox and Nayler when they visited Northampton, marveled at the way Nayler "confounded the deceit" of the audience and thought he was a greater speaker than Fox. (18)

Christopher Hill has argued that many people in the movement regarded Nayler as the "chief leader" and the "head Quaker in England". (19) Colonel Thomas Cooper pointed out in the House of Commons: "He (Nayler) writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect." (20) Even one of his critics, John Deacon, conceded that he was "a man of exceeding quick wit and sharp apprehension, enriched with that commendable gift of good oratory with a very delightful melody in his utterance." (21)

According to H. Larry Ingle: "Some people, Friends as well as outsiders, looked on Fox as a bit 'strange' - a word used by a close observer and companion - and wondered at the way other Quakers tended to be quiet in his presence and defer to him during meetings. In personal debate Nayler was quick and intelligent. His writings were incisive and polished, whereas Fox in his writings tended to plod and stumble. if not as charismatic, Nayler still attracted a bevy of followers of an intense type, people who practically worshiped him as the harbinger of a new age. They were willing to follow him anywhere and to do practically anything to demonstrate their commitment. Some of the most vocal of these acolytes were women, and this fact led detractors, then and later, to see an insidious influence at work: either he had some mysterious hold over these women or they themselves were temptress using their wiles to turn his head." (22)

No written rules governed the Society of Friends because it was a kind of community of equals, all committed to the same goals and having the interests of the group at heart. The question of leadership was left open. Fox and Nayler had been involved in the movement together almost from the beginning and shared many days and nights of travelling, and co-authored pamphlets and epistles. However, by 1655 Fox came infrequently to London, preferring to continue his travels in the countryside, and some regarded Nayler as the movement's leader. This was especially true of Martha Simmonds, "an intelligent and independent person, author of several moving pamphlets about spiritual seeking and apocalyptic hopes." (23)

Fox became concerned about how Nayler was winning such a fervent band of disciples in London. It seemed to Fox that Nayler was erecting a base of influence that gave him a strength and a prestige independent of Fox. In the meetings he held he began talking about "wicked mountains and parties crying against him". With the ability to win followers, "Nayler posed a threat of major proportions to Fox. No movement can follow two masters, as Fox realized." (24)

Oliver Cromwell was also becoming concerned about the popularity of Nayler. As Christopher Hill pointed out: "Nayler was a leader of an organized movement which, from its base in the North, had swept with frightening rapidity over the southern counties. It was a movement whose aims were obscure, but which certainly took over many of the aims of the Levellers, and was recruiting former Levellers and Ranters... M.P.s were anxious to finish once and for all with the policy of religious toleration which, in their view, had been the bane of England for a decade. The government of the Protectorate, satisfactorily conservative in many ways, was still in their view woefully unsound in this respect. The fact that its relative tolerance resulted from its dependence on the Army only heightened the offence." (25)

In January 1656, Fox was imprisoned in Launceston. Martha Simmonds travelled to Launceston to meet with Fox, and to state her view that Nayler was the leader of the movement. Fox wrote to Nayler an indignant letter reporting that "she (Simmonds) came singing in my face, inventing words" and informing him that his heart was rotten. In September 1656, Fox was released from prison and proceeded to Exeter, where he demanded that Nayler acknowledge subservience, and when Nayler refused to kiss his hand told him insultingly to kiss his foot instead. (26) They parted bitterly, and later Fox remembered this episode as a critical threat to the movement: "So that after I had been warring with the world, now there was a wicked spirit risen up amongst Friends to war against". (27)

Palm Sunday Re-enactment

In October 1656, Nayler re-enacted the Palm Sunday arrival of Christ in Jerusalem. Seated on an ass he was escorted into Bristol by women strewing branches in his path. Oliver Cromwell and other members of the House of Commons were horrified by Nayler allowing himself to be hailed by devoted disciples as a new Messiah. Nayler was arrested. Philip Skippon, a staunch presbyterian and the major-general in charge of the London area, complained that Cromwell's policy of toleration had fostered a Quaker threat: "Their great growth and increase is too notorious, both in England and Ireland; their principles strike at both ministry and magistracy. Many opinions are in this nation (all contrary to the government) which would join in one to destroy you, if it should please God to deliver the sword into their hands." (28)

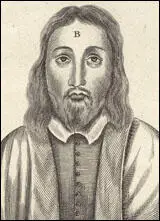

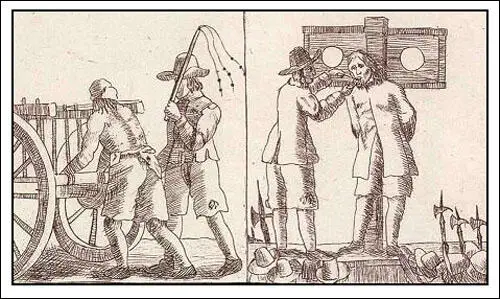

At his trial before Parliament, Nayler declared that he had enacted a "sign" without mistaking himself for Christ. A few members were prepared to accept his account, but the majority were determined on punishment and disagreed only as to its extent. By the narrow margin of 96 to 82, a motion to put him to death was defeated, and after further debate it was resolved on 16 December that Nayler be whipped through the streets by the hangman, exposed in the pillory, have his tongue bored through with a red-hot iron, and have the letter B (for blasphemy) branded on his forehead. He was then to be returned to Bristol and compelled to repeat his ride in reverse while facing the rear of his horse, and finally he was to be committed to solitary confinement in Bridewell Prison for an indefinite period. (29)

Nayler's punishment was carried out in every detail, including 300 lashes that tore all the skin off his back, and the concluding scene at the pillory was witnessed by a large crowd that included Thomas Burton, the MP for Westmorland. He approved of the punishment but admired Nayler's stoicism: "He put out his tongue very willingly, but shrinked a little when the iron came upon his forehead. He was pale when he came out of the pillory, but high-coloured after tongue-boring… Nayler embraced his executioner, and behaved himself very handsomely and patiently." (30)

Christopher Hill has argued that Oliver Cromwell used the Nayler incident to suppress the Quakers: "So conservatives in Parliament seized the occasion to put the whole Quaker movement in the dock, and the government's religious policy too. The hysteria of M.P.s' contributions to the debate shows how frightened they had been, how delighted they were to seize the opportunity for counterattacked. And the conservatives won their showdown with the government. Nayler was tortured, to discourage the others. Cromwell queried the authority for Parliament's action against Nayler, but ultimately he made political use of the Nayler case to manoeuvre the Army into accepting Parliament's Petition and Advice, a constitution which established something like the traditional monarchy and state church, and drastically limited the area of religious toleration." (31)

Fox refused to sign a petition asking that Nayler's punishment be remitted. Fox also endorsed Parliament's actions against Nayler: "If the seed of the serpent speaks and says he is Christ that is the liar and the blasphemy and the ground of all blasphemy." It has been pointed out that Nayler had been convicted for something that Fox had done, claimed to be the "Son of God".Alexander Parker argued that by alienating the Naylerites, Fox was weakening the movement. Robert Rich, a successful merchant and ship owner from London, was criticised by Fox for his support and continued public defense of the jailed Quaker. (32)

Fox believed that Nayler had been attracting the following of the Ranters. This was supported by Thomas Collier who wrote in 1657 that "any that know the principles of the Ranters" may easily recognize that Quaker doctrines are identical. Both would have "no Christ but within; no Scripture to be a rule; no ordinances, no law but their lusts, no heaven nor glory but here, no sin but what men fancied to be so, no condemnation for sin but in the consciences of ignorant ones". Only Quakers "smooth it over with an outward austere carriage before men, but within are full of filthiness". (33)

Fox's conflict with Nayler highlighted the disruptive side to the individualistic faith of the Quakers. Fox realised he would need to find a way to impose discipline. On the question of individualism versus authority, Fox came down on the side of authority. "A two-level system was erected, a meeting at a local level, a larger and more distant one a rung higher, forming a systematic check on a potential dissident's outward expression of inward leadings as determined by those gripping the instruments of power." (34)

It has been argued that: "The Quaker consensus came down on the side of discipline, organization, common sense. The eccentricities of Quakerism were quietly dropped.. Going naked for a sign, miracles and the other individualist exuberances of early Quakers and Ranters disappeared as the inner light adapted itself to the standards of this commercial world where yea and nay helped one to prosper. It is pointless to condemn this as a sell-out as to praise its realism: it was simply the consequence of the organized survival of a group which had failed to turn the world upside down." (35)

Fox's attempt to distance himself from Nayler's "extremism" did not work. Oliver Cromwell decided to remove Quakers from the army and from their positions as justices of the peace. (36) Fox now instructed Quakers all over the country to record their sufferings if they were arrested for attending meetings or for refusing to pay their tithes and not swearing oaths. He directed that "a true and a plain copy of such suffering be sent to London" to demonstrate to Cromwell and the House of Commons the extent of the persecution they had ordered. (37)

Last Years

For most of his time in prison he was kept at hard labour picking hemp. Although in poor health Nayler managed to continue to write on spiritual topics and a number of his pamphlets were smuggled out of prison and published. He also expressed regret for any damage the movement had suffered. Leo Damrosch has pointed out that "later writers misleadingly but understandably interpreted his reaction as a wholesale 'repentance'. If anything he seems to have felt that his symbolic gesture had been cruelly misunderstood by those who ought to have appreciated it." (38)

In September of 1659, nearly three years after Nayler entered Bridewell, the Rump Parliament declared an amnesty for Quaker prisoners and he was set free. He went to Reading to meet Fox but he refused to see him. It was not until January 1660 that he agreed to talks: "Fox exacted a high psychological price for his follower's apostasy: Nayler had to kneel before Fox and beg forgiveness." (39)

Nayler was highly critical of Cromwell's government. He published a pamphlet calling on the Long Parliament to "set free the oppressed people". Nayler explained that Quakers were disappointed by Cromwell's promises of reform. "The simple-hearted" supporters of Parliament, who had been drawn in by "fair pretences" were beginning "to leave you and return home, all men disappointed of their expectation". (40)

In October 1660 James Nayler set out on a journey to his Yorkshire home, but at Huntingdon he was robbed and beaten. Rescuers took him to the nearby home of a Quaker, where he died. It is claimed that his last words were: "There is a spirit which I feel that delights to do no evil, nor to revenge any wrong, but delights to endure all things, in hope to enjoy its own in the end. Its hope is to outlive all wrath and contention, and to weary out all exaltation and cruelty, or whatever is of a nature contrary to itself. It sees to the end of all temptations. As it bears no evil in itself, so it conceives none in thoughts to any other. If it be betrayed, it bears it, for its ground and spring is the mercies and forgiveness of God. Its crown is meekness, its life is everlasting love unfeigned; it takes its kingdom with entreaty and not with contention, and keeps it by lowliness of mind. In God alone it can rejoice, though none else regard it, or can own its life. It is conceived in sorrow, and brought forth without any to pity it, nor doth it murmur at grief and oppression. It never rejoice but through sufferings; for with the world's joy it is murdered. I found it alone, being forsaken. I have fellowship therein with them who lived in dens and desolate places in the earth, who through death obtained this resurrection and eternal holy life." (41)

Primary Sources

(1) James Nayler, Saul's Errand to Damascus (1654)

Is this a time to chide, and be angry, and pick quarrels? and (if you must needs do so) can you find no other objects of your indignation but the Lord's disciples? but peaceable, holy, humble, self-denying men? Is not the work of the ministry to preach the gospel? Is not the sword of the magistrate appointed to the punishment of evildoers, and to the praise of them that do well? Are you incumbent in your duties? Are you laying out your talents to the end they were given you? or are you mistaken in the thing? When did you proclaim war against drunkards, swearers, common blasphemers, enemies to the Lord and his people? have you none of those amongst you? or are your high-flown contending spirits gone beyond such slender wrestlings that you scorn to encounter with any below the degree of a saint? The Lord open your eyes, and let you see, and give you hearts to consider your several duties. But tell me, ye sons of Levi (as ye call yourselves), ye that pretend a jus divinum to persecution: What will ye say when the Son of Man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, and shall sit upon the throne of his glory, and all nations shall be gathered before him? Mind ye what will be the great work of that great day; your petition will surely then be heard. I beseech you read the paper of causes set down to be first heard at that tribunal, in Matt. 25:31 to the end of the chapter; and the Lord let it dwell upon your hearts forever.

These are to let thee know that the only wise God at this time hath so by his providence ordered it, in the north parts of Lancashire, that many precious Christians (and so for many years accounted, before the nickname "Quakers" was heard of) have for some time past forborne to concorporate in parochial assemblies, wherein they profess themselves to have gained little of the knowledge of Jesus Christ. And it is and hath been put upon their hearts to meet often (and on the Lord's day constantly) at convenient places, to seek the Lord their Redeemer, and to worship him in Spirit and in truth, and to speak of such things (tending to mutual edification) as the good Spirit of the Lord shall teach them, demeaning themselves without any offense given to any that truly fear the Lord.

But true it is that some men and interests of those parts do take great offense at them and their Christian and peaceable exercises; some, because they have witnessed against pride and luxuriant fullness, have therefore come armed with sword and pistols (men that never drew a sword for the interest of the Commonwealth of England, perhaps against it) into their assemblies in time of their Christian performances, and have taken him whom the Lord at that instant had moved to speak to the rest, and others of their assembly (after they had haled and beaten them) and carried them bound hand and feet into the open fields, in the cold of the night, and there left them to the hazard of their lives, had not the Lord of life owned them, which he did in much mercy. Others have had their houses broken in the night, and entered by men armed as aforesaid (and disguised) when they have been peaceably waiting upon God with their own and neighbor families; and yet these humble persecuted Christians would not (even in these cases of gross and intolerable affronts acted equally against the peace of the nation as against them) complain, but expressed how much (in measure) of their Master's patience was given them in breathing out their Master's gentle words, "Father forgive them; they know not what they do." Who have at any time borne such unheard-of persecution with so mild spirits? only they in whom persecuted Christ dwells: these poor creatures know how their Master fared and rejoice to suffer with him, by whom alone they hope to be glorified, and are as well content to suffer as to reign with Christ. But how unwillingly do we deny ourselves, and take up our cross and follow Christ? and yet a necessity lies upon us (if we will be the Lord's disciples) to take up our cross daily and follow him. How is it then, that the crown of pride is so long upon the head of persecutors? How is it that such men should dare to divide the people of England, to trouble the Council of State (in the throng of business concerning the management and improvement of all the mighty series of glorious providence made out to this infant Commonwealth) with such abominable misrepresentations of honest, pious, peaceable men, who desire nothing more than to glorify their God in their generation, and are and have been more faithful to the interest of God's people in the nation than any of the contrivers of the petition, as will easily be made appear if we may take for evidence what they themselves have often said of the Parliament and Army, and their friends and servants, publicly and privately; and 'tis well known their judgments are the same; but that the publication thereof will not safely consist with the enjoyment of their large vicarages, parsonages, and augmentations, whereby they are lifted up above their brethren, and exalt themselves above all that are called God's people in these parts.

However, reader, we need not fear; we hope the Lord will never suffer that monster persecution again to enter within the gates of England's Whitehall: they that sit in council there know well enough who it was that so often assembled to consult how they might take Jesus by subtlety and kill him: they were men of no lower condition than chief priests, scribes, and elders of the people; and if ever these petitioners should but appear before them to whom they have directed their petition, my heart deceives me if they be not accounted such.

Reader, I would not preface thee into a good opinion of these suffering objects of such men's wrath; but read their paper here put into thy hand, by them written, upon the occasion of this petition, and several snares and temptations laid before them on purpose to entrap them; and if by them thou canst find cause to pity these oppressed little ones, have them in thy remembrance when thou goest to the throne of grace, where my prayers shall meet thine, for them.

(2) James Nayler, A Discovery of the Man of Sin (1655)

The thing that was seen concerning Newcastle: all his pillars to be dry, and his trees to be bare, and much nakedness … for it's a stony ground, and there is much briars and thorns about her, and many trees have grown wild long, and have scarce earth to cover their roots, but their roots are seen, and how they stand in the stones, and these trees bears no fruit, but bears moss, and much wind pierces through, and clatters them together, and makes the trees shake, but still the roots are held among the stones, and are bald and naked.

(3) Leo Damrosch, James Nayler : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September, 2004)

As the puritan establishment consolidated its position, radical sects were increasingly regarded as transgressive. Marginal groups such as the Levellers, the Diggers, and the shadowy Ranters were efficiently suppressed. Harder to control were the Quakers, who began to spread their message widely throughout the north, acquiring a valuable protector in Margaret Fell of Swarthmoor Hall in Lancashire, who soon took on the role of unofficial co-ordinator of the movement. Nayler and Fox stayed together at Swarthmoor in 1652 and succeeded in persuading Margaret Fell's husband, Judge Thomas Fell, though he did not become a convert, to extend his protection...

The travelling evangelists were particularly repugnant to the ministers because they made a habit of interrupting religious services to proclaim their message, and demanded abolition of the benefices and tithes that supported the 'hireling priests', as they called them. It was a fixed Quaker principle to accept no payment for preaching and to address any who might listen, often speaking in the open air, rather than to form settled congregations. When the Westmorland ministers complained that unauthorized preachers were invading their territory, Nayler replied, 'It is true, our habitation is with the Lord, and our country is not of this world' (J. Nayler, Several Petitions Answered, 1653, 5). Some three dozen Lancashire ministers appeared at Lancaster quarter sessions to lodge a complaint against Fox and Nayler, but Judge Fell interceded on their behalf and they were released.

Hostilities continued as local people were encouraged to harass the unwelcome visitors, sometimes stoning and beating them in unruly mobs, and soon Nayler and Fox were arrested at Kirkby Stephen and imprisoned at Appleby, Westmorland, until April of 1653. For the rest of that year and throughout 1654 Nayler travelled and preached extensively in the north, winning admiration for the power and cogency of his speaking.

(4) Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991)

Nayler was a leader of an organized movement which, from its base in the North, had swept with frightening rapidity over the southern counties. It was a movement whose aims were obscure, but which certainly took over many of the aims of the Levellers, and was recruiting former Levellers and Ranters. Bristol was the second city of the kingdom, where the Quakers had many followers. Above all, M.P.s were anxious to finish once and for all with the policy of religious toleration which, in their view, had been the bane of England for a decade. The government of the Protectorate, satisfactorily conservative in many ways, was still in their view woefully unsound in this respect. The fact that its relative tolerance resulted from its dependence on the Army only heightened the offence.

So conservatives in Parliament seized the occasion to put the whole Quaker movement in the dock, and the government's religious policy too. The hysteria of M.P.s' contributions to the debate shows how frightened they had been, how delighted they were to seize the opportunity for counterattacked. And the conservatives won their showdown with the government. Nayler was tortured, to discourage the others. Cromwell queried the authority for Parliament's action against Nayler, but ultimately he made political use of the Nayler case to manoeuvre the Army into accepting Parliament's Petition and Advice, a constitution which established something like the traditional monarchy and state church, and drastically limited the area of religious toleration.