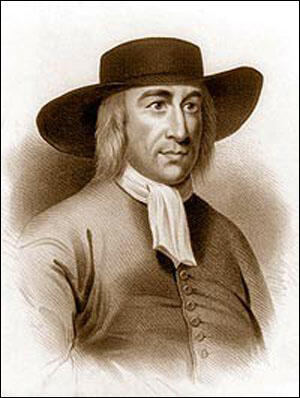

Francis Howgill

Francis Howgill was born in a small village near Grayrigg, Westmorland , in about 1618. In a brief autobiography he became extremely interested in religion when he was twelve years old. (1) He seems to have been university-educated, although his name does not appear in the registers of either Oxford or Cambridge. As a young man he considered joining the Independents or the Baptists. (2)

In 1652 Howgill heard the preaching of George Fox, a young man who had been travelling the country for the last ten years. According to Pauline Gregg he had came to the simple realization that the spirit of God was within each man, and that the knowledge of Christ was an inner light that could reveal itself at any time without the help of dogma, form, or ceremony. "A man need be equipped with nothing but a humble spirit and a belief in God and Jesus Christ. No prayer-book, no preacher, no sacrament, no church, who needed to guide him - only the witness in his conscience." (3)

Quakerism

Fox refused to bow or to take off his hat to anyone, to use the pronouns "Thee" and "Thou" to all men and women whether they were rich or poor, never to call the days of the week or the months of the year by their names but only by their numbers. He would enter church services and denounce the preacher in the midst of his sermon. Fox attempted to teach the conviction of moral perfection and "almost a personal infallibility, of spirit-inspired utterance". (4) In one pamphlet Fox stated: "Did not the Whore of Rome give you the name of vicars... and parsons and curates?" (5)

During this period Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as Quakers. This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (6)

Francis Howgill was quick to recognize Fox's wisdom, but he was less spiritually ready to embrace the full implications of Quakerism. The Inheritance of Jacob is indeed subtly different from many other Quaker autobiographies in that it is expansive about the doubts and insecurities occurring after the first encounter with Fox. (7)

Over the next few years Howgill toured the country with his friend Edward Burrough, but the two men were especially important in London. One of the men who the couple converted in 1654, William Crouch, described them as "the Apostles of this City in their Day." (8)

Francis Howgill and James Nayler

Another important Quaker preacher was James Nayler who was the leading figure in the movement in London. Nayler was an accomplished speaker and writer, as well as a creative thinker. William Dewsbury, who had the opportunity to watch both Fox and Nayler when they visited Northampton, marveled at the way Nayler "confounded the deceit" of the audience and thought he was a greater speaker than Fox. (9)

Christopher Hill has argued that many people in the movement regarded Nayler as the "chief leader" and the "head Quaker in England". (10) Colonel Thomas Cooper pointed out in the House of Commons: "He (Nayler) writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect." (11) Even one of his critics, John Deacon, conceded that he was "a man of exceeding quick wit and sharp apprehension, enriched with that commendable gift of good oratory with a very delightful melody in his utterance." (12)

No written rules governed the Society of Friends because it was a kind of community of equals, all committed to the same goals and having the interests of the group at heart. The question of leadership was left open. Fox and Nayler had been involved in the movement together almost from the beginning and shared many days and nights of travelling, and co-authored pamphlets and epistles. However, by 1655 Fox came infrequently to London, preferring to continue his travels in the countryside, and some regarded Nayler as the movement's leader. This was especially true of Martha Simmonds, "an intelligent and independent person, author of several moving pamphlets about spiritual seeking and apocalyptic hopes." (13)

Fox became concerned about how Nayler was winning such a fervent band of disciples in London. It seemed to Fox that Nayler was erecting a base of influence that gave him a strength and a prestige independent of Fox. In the meetings he held he began talking about "wicked mountains and parties crying against him". With the ability to win followers, "Nayler posed a threat of major proportions to Fox. No movement can follow two masters, as Fox realized." (14)

Howgill and his friend Edward Burrough spent the winter of 1655–6 in Ireland, making friends of people such as John Perrot. When they returned to London they found the dispute between Fox and Nayler was harming the movement. Howgill went as far as saying that their main enemy was "within". Both Howgill and Burrough were involved in the disciplining of James Nayler and his followers. (15) Though a critic of Nayler, Howgill believed that the Bible could be literally interpreted, and endorsed going "naked as a sign". (16)

Oliver Cromwell

Howgill, like most leading Quakers, was highly critical of Oliver Cromwell and described him as the man of "subtlety and deceit". (17) Cromwell decided to remove Quakers from the army and from their positions as justices of the peace. (18) George Fox now instructed Quakers all over the country to record their sufferings if they were arrested for attending meetings or for refusing to pay their tithes and not swearing oaths. He directed that "a true and a plain copy of such suffering be sent to London" to demonstrate to Cromwell and the House of Commons the extent of the persecution they had ordered. (19)

James Nayler was released from prison in 1659. He was also opposed to Cromwell's government. He published a pamphlet calling on the Long Parliament to "set free the oppressed people". Nayler explained that Quakers were disappointed by Cromwell's promises of reform. "The simple-hearted" supporters of Parliament, who had been drawn in by "fair pretences" were beginning "to leave you and return home, all men disappointed of their expectation". (20)

The Restoration

In 1658 Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (21)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (22)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (23)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (24)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (25)

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and on the twelfth anniversary of the regicide, on 30th January 1661, their bodies were disinterred and hung from the gallows at Tyburn. (26) Cromwell's body was put into a lime-pit below the gallows and the head, impaled on a spike, was exposed at the south end of Westminster Hall for nearly twenty years. (27)

Imprisonment and Death

The Restoration divided Quakers into two groups: those who found reassurance in George Fox's message to trust in God and the inevitable workings of God's will, and those who expected the Society of Friends to take a more militant stance. Edward Burrough was one of those who sought confrontation with the authorities. Burrough was arrested on 1 June 1661. He refused to back down and he died aged twenty-nine in Newgate prison on 14 February 1663. (28)

Howgill views were similar to Burrough. After Charles II became king he published Chosen Madness for Thy Crown (1660). Howgill was found guilty of praemunire at Appleby in 1663 after refusing to swear the oath of allegiance. This sentence being passed and he was imprisoned for life. In 1665 he showed that he no longer believed in an eventual Quaker triumph over adversity, resignedly committing himself to suffering "though the day be dark and gloomy" (29)

Francis Howgill became ill while in prison and he died on 11 February 1669.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Howgill, A General Epistle to the Seed of God (1665)

Dear Friends everywhere who have believed in our Lord Jesus Christ, and (who have been) called with an holy calling to the great salvation of God which is made manifest in this day of his power. Keep your first love, and let not the threats of men, neither the frowns of the world affright you from that which you have prized more than all the world. Now the sun is up, and a time of scorching is come, and that which hath no root will wither. Now every ground will be tried, and blessed is the good that brings forth the Seed which must inherit the promise.

Oh, let not the care of this present life choke that which God hath begotten. Seeing the Lord hath so marvelously wrought for us hitherto, in the midst of great oppression, let not your faith fail, nor your confidence in God who delivered Jacob of old out of his adversary, and Israel out of all his troubles, whose care is over his people now.

Having seen the emptiness of the world and its way and worship, let nothing blind your eyes again, and let not the things present nor the things to come separate you from the love of God in Christ Jesus. Mind not them that draw back to perdition, but let it teach you all more diligence, to be a those who press after glory, immortality, and everlasting life.

The way of God was ever hated by the world and the powers thereof. Never heed the rough spirits nor the heavy, for their bound is set, and their limit known; but mind the Seed, which hath dominion over all. And forsake not the assembling of yourselves together in which you have found God and his promise and power and blessing amongst you, your understanding opened.

Oh, rather suffer all tings than let go that which you have believed; for whoso doth, will lose the evidence of God's spirit in them, and their peace will be lost.

(2) Catie Gill, Edward Burrough : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3 January, 2008)

Howgill joined with the Quaker Edward Burrough, who was his companion in Bristol (1654), London (1654), and Ireland (1655–6). The work in London was particularly demanding because high emotions were soon roused at the large Quaker meetings, as Howgill's frequent letters show. Caught up in the fervour, Howgill once tried, unsuccessfully, to heal a lame boy. Sometimes the letters show him despairing of making an impact, and, indeed, he later viewed the great fire of 1666 as an act of divine retribution for London's ungodliness.

Howgill and Burrough ministered throughout Ireland in the winter of 1655–6, leaving Nayler in London but upon their banishment from Ireland in 1656 by Henry Cromwell, they returned to a now divided London. Howgill was critical of Nayler's ministry and supporters long before Nayler notoriously re-enacted Christ's entry into Jerusalem in October, which led to his conviction for blasphemy...

The little that can be extracted from contemporary letters about Howgill's personal life presents a man who prioritized his spiritual commitments. Dorothy Howgill, his wife and the mother of at least one child, died in March 1656. After the events in London subsided, Howgill went through a relatively quiet period, which may have reflected his changing domestic circumstances. He was travelling again in Scotland by 1657, and turning up on the list of names of those imprisoned in London in 1661, so his children must have been cared for by someone other than himself. Howgill certainly remarried, but very little is known about his second wife. She may have been from Newcastle, and she gave birth to a child, Henry, on 27 September 1665; but her name is unknown, as is the date of their union. She is referred to, if at all, within her prescribed role as mother and wife.