Mary Dyer

Mary Barrett was born in about 1611. She married William Dyer, a milliner and member of the Fishmongers' Company, probably in St Martin-in-the-Fields, Middlesex, on 27 October 1633. Their first child, William, was baptized in October 1634 and buried there only three days later. The Dyers were Puritans and soon after the death of their child they travelled to America and their second son was baptized into the Boston church on 20 October 1635. (1)

John Winthrop had arrived with 700 settlers five years earlier and was appointed governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. One of the settlers, Anne Hutchinson, began to claim that good conduct could be a sign of salvation and affirmed that the Holy Spirit in the hearts of true believers relieved them of responsibility to obey the laws of God. She also criticised New England ministers for deluding their congregations into the false assumption that good deeds would get them into heaven. Complaints were made about Hutchinson's teachings and Winthrop, called her to appear before the authorities. (2)

Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson

Mary Dyer was a supporter of Hutchinson took her hand in court, an action which identified her as a "Hutchinsonian" or an "antinomian". During her cross-examination she claimed that she had received a revelation from God. To the Puritan authorities this was blasphemy and she was banished from the community. Interest now turned to Mary and Winthrop ordered the exhumation of the body of her dead child. Winthrop later recalled: "It was of ordinary bigness; it had a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape's; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp; two of them were above one inch long, the other two shorter; the eyes standing out, and the mouth also; the nose hooked upward; all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales, like a thornback, the navel and all the belly, with the distinction of the sex, were where the back should be, and the back and hips before, where the belly should have been; behind, between the shoulders, it had two mouths, and in each of them a piece of red flesh sticking out; it had arms and legs as other children; but, instead of toes, it had on each foot three claws, like a young fowl, with sharp talons." (3)

Dyer and Hutchinson now joined Roger Williams and his colony on Rhode Island. The colony was a haven of religious toleration and admitted Jews, Ranters, Fifth Monarchists and other religious dissenters. At the time the island was a "heretic's haven" but had been nicknamed "Rogues' Island" or "Island of Errors". (4) Within a year there was dissension among the leaders, and the Dyers and several other inhabitants moved to the south end of the island, establishing the town of Newport. Williams envisioned a union of all four settlements on the Narragansett Bay (Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport) and went to England where he obtained a patent bringing the four towns under one government. William Dyer was elected the General Recorder for the entire colony in 1648. (5)

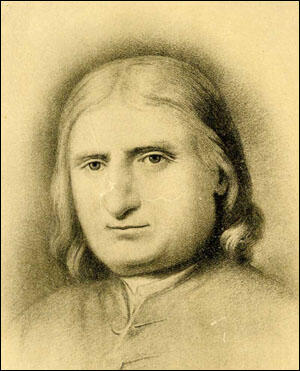

George Fox

In about 1650 Mary returned to England. It is claimed that while in the country she heard about the activities of George Fox. During this period Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as Quakers. This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (6)

Fox refused to bow or to take off his hat to anyone, to use the pronouns "Thee" and "Thou" to all men and women whether they were rich or poor, never to call the days of the week or the months of the year by their names but only by their numbers. He would enter church services and denounce the preacher in the midst of his sermon. Fox attempted to teach the conviction of moral perfection and "almost a personal infallibility, of spirit-inspired utterance". (7) In one pamphlet Fox stated: "Did not the Whore of Rome give you the name of vicars... and parsons and curates?" They "set up your schools and colleges... whereby you are made ministers?" (8)

Quaker Missionary

Mary Dyer returned to Boston in the early months of 1657. Of all the New England colonies, Massachusetts was the most active in persecuting the Quakers. When the first Quakers arrived in Boston in 1656 there were no laws yet enacted against them, but this quickly changed, and punishments were meted out with or without the law. The Reverend John Norton of the Boston church, clamored for the law of banishment upon pain of death. The punishments imposed on Quakers included the stocks and pillory, lashes with knotted whip, fines, imprisonment, mutilation (having ears cut off), banishment and death. When whipped, women were stripped to the waist, thus being publicly exposed, and whipped until bleeding. (9)

As soon as Dyer arrived in Boston she was immediately recognised and imprisoned. Dyer's husband had to come to get her out of jail, and he was bound and sworn not to allow her to lodge in any Massachusetts town. (10) Dyer continued to travel in New England to preach her Quaker message, and in early 1658 was arrested in the New Haven Colony, and then expelled for preaching that women and men stood on equal ground in church worship and organization. Anti-Quaker laws had been enacted there, and after Dyer was arrested, she was "set on a horse", and forced to leave. (11)

In June 1658 three Quaker activists, Christopher Holder, John Copeland and John Rous arrived in Boston. They were all arrested and sentenced to having their right ears cut off. Dyer was furious when she heard the news and along with the London merchant William Robinson and a Yorkshire farmer named Marmaduke Stephenson, decided to go to Boston to protest these acts of cruelty. The three were arrested and banished, but Robinson and Stephenson returned and were again imprisoned. Mary Dyer went back to protest at their treatment, and was also imprisoned. (12)

Quaker Martyr

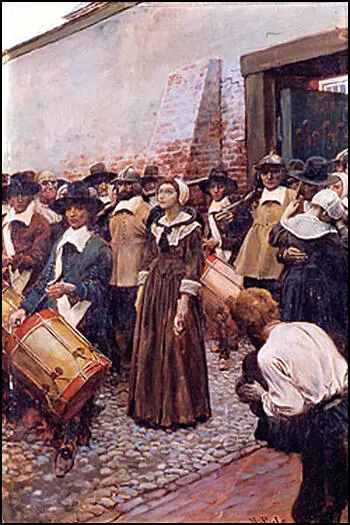

On 19 October 1659, Dyer, Robinson and Stephenson were brought before John Endicott, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (13) Endicott explained to them: "We have made many laws and endeavored in several ways to keep you from among us, but neither whipping nor imprisonment, nor cutting off ears, nor banishment upon pain of death will keep you from among us. We desire not your death." Having met his obligation to present the position of the colony's authorities, he sentenced them to death. Endicott told her, "Mary Dyer, you shall go from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, and there be hanged till you be dead." She replied, "The will of the Lord be done." When Endicott directed the marshall to take her away, she said, "Yea, and joyfully I go." (14)

The date set for the executions of Dyer, Robinson and Stephenson was 27 October 1659. (15) Armed soldiers escorted the prisoners to the place of execution. Dyer walked hand-in-hand with the two men. When she was asked about this inappropriate closeness, she responded instead to her sense of the event: "It is an hour of the greatest joy I can enjoy in this world. No eye can see, no ear can hear, no tongue can speak, no heart can understand the sweet incomes and refreshings of the spirit of the Lord which now I enjoy." (16)

Dyer watched Robinson and Stephenson being executed. Her arms and legs were bound and her face was covered with a handkerchief. As she waited to climb the ladder an order of a reprieve was announced. A petition from her son, William, had given the authorities an excuse to avoid her execution. Dyer spent the winter in Rhode Island but, in May 1660, returned once again to Boston. (17) In a letter explaining her actions, she protested against the "unrighteous laws", taking on the mantle of prophet and religious martyr and condemning "the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death". (18)

Dyer appeared before Governor John Endicott on the 31st May, 1660. He asked if she was still a Quaker and she replied: "I own myself to be reproachfully so called." Endicott then passed his judgment: "Sentence was passed upon you the last General Court; and now likewise - You must return to the prison, and there remain till to-morrow at nine o'clock; then thence you must go to the gallows and there be hanged till you are dead.... Therefore prepare yourself tomorrow at nine o'clock." Dyer then explained her actions: " I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them." (19)

On 1 June 1660, at nine in the morning, Mary Dyer was escorted to the gallows. While on the scaffold she was given the opportunity to save her life if she renounced her religious beliefs. She replied: "Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death. Nay, I came to keep blood guiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death." (20)

According to Edward Burrough, Dyer died "sweetly and cheerfully" on the gallows on 1 June 1660. Burrough believed fellow Quakers believed that Mary Dyer "did hang as a flag for them to take example by" (21). Charles II responded to this event by asking Governor Endicott for less severe religious laws, and she was the last but one Quaker to be hanged in Boston. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) Catie Gill, Mary Dyer: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September, 2004)

Dyer [née Barrett], Mary (d. 1660), Quaker martyr in America, of whom all that is known of her parentage is her maiden name, married William Dyer (bap. 1609), a milliner and member of the Fishmongers' Company, probably in St Martin-in-the-Fields, Middlesex, on 27 October 1633. The couple had several children, of whom the eldest, William, was baptized at St Martin-in-the-Fields in October 1634 and buried there only three days later. The second son, William, was born in Massachusetts, where his parents had emigrated, and was baptized into the Boston church on 20 October 1635, one week after his parents had been admitted to its membership. The third, who was stillborn and badly misshapen after a breech birth, brought Dyer to notoriety. She was reputed to have given birth to a monster.

The case of Mary Dyer's stillborn child came to light in March 1638, by which time the prophet Anne Hutchinson, both a friend and her midwife, was on trial. When the charge of "traducing the ministers" was upheld against Hutchinson, Mary Dyer took her friend's hand in court, an action which identified her as a ‘Hutchinsonian' or, more pejoratively, an antinomian. Interest in her led John Winthrop to exhume the body of her infant: sensational accounts describe the appearance of the body as part-fish, part-bird, part-beast.

The Dyers, escaping the severity of the puritan authorities, then made their home first in Portsmouth and then in Newport, Rhode Island. William became general recorder of the colony. In 1650 or 1652 Mary returned to England, where she became a Quaker. Her return to Boston, in January or February 1657, was marked by her immediate imprisonment. In 1659 she was banished from Boston, but she was not daunted by the threat of the death penalty should she return. Having returned once more, she appeared in a Boston court alongside her fellow Quakers William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson on 20 October 1659. Though the men met their ends on the gallows, Dyer was dramatically reprieved even as she climbed the scaffold. She spent the winter in Rhode Island but, in May 1660, returned once again to Boston.

(2) Governor John Endicott and Mary Dyer in court (31st May, 1660)

John Endicott: Are you the same Mary Dyer that was here before?

Mary Dyer: I am the same Mary Dyer that was here the last General Court.

John Endicott: You will own yourself a Quaker, will you not?

Mary Dyer: I own myself to be reproachfully so called.

John Endicott: Sentence was passed upon you the last General Court; and now likewise�You must return to the prison, and there remain till to-morrow at nine o'clock; then thence you must go to the gallows and there be hanged till you are dead.

Mary Dyer: This is no more than what thou saidst before.

John Endicott: But now it is to be executed. Therefore prepare yourself to-morrow at nine o'clock.

Mary Dyer: I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them.

(2) Mary Dyer, speech on the scaffold when she was given the opportunity to save her life. (1st June, 1660)

Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death. Nay, I came to keep blood guiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death.