Elizabeth Hooton

Elizabeth Carrier was born in Ollerton, Nottinghamshire, in about 1600. On 11 May 1628 she married Oliver Hooton, a prosperous farmer. Their son Samuel was baptized on 4 May 1633, but they subsequently moved to Skegby near Mansfield. There were at least five other children: Thomas, John, Josiah, Oliver and Elizabeth. (1)

After leaving the Church of England, Hooton appears to have been active in her local Baptist community and perhaps as a preacher, but according to her son Oliver, writing years later "after some time finding them that they were not upright hearted to the Lord but did his work negligently", she parted company with them. (2)

It is claimed that Elizabeth Hooton was one of the first people to be "convinced" by George Fox after hearing him speak in Nottingham in 1647. Her husband seems to have opposed his wife's new beliefs as a Quaker "in so much that they had like to have parted". However, he later returned home and joined the movement and the Hooton household became a major base in the area. (3)

Fox wrote in his journal that in about 1649 Elizabeth Hooton's "mouth was opened to preach the gospel" (4) Gerard Croese, a 17th century historian suggested that she "was the first of her sex among the Quakers who attempted to imitate men, and preach" and suggested that Hooton was a role model for women: "after her example, many of her sex had the confidence to undertake the same office". (5)

George Fox

During this period George Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as Quakers. This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (6)

Quakers refused to bow or to take off their hat to anyone, to use the pronouns "Thee" and "Thou" to all men and women whether they were rich or poor, never to call the days of the week or the months of the year by their names but only by their numbers. Quakers like Hooton would enter church services and denounce the preacher in the midst of his sermon. Fox attempted to teach the conviction of moral perfection and "almost a personal infallibility, of spirit-inspired utterance". (7)

Imprisonment of Elizabeth Hooton

Hooton soon troubled the authorities with her preaching and her protestations against the corruption of the clergy. Her first recorded imprisonment appears to have been in Derby about 1651 for criticising a minister. In 1652 she was imprisoned in York Castle for abusing a minister and his congregation in Rotherham at the close of their worship. With other Quakers, including Mary Fisher and Thomas Aldham, she was a signatory to False Prophets and False Teachers (1652), a tract attacking paid ministry, written in the castle. (8)

Elizabeth Hooton's experiences at York led her to write to Oliver Cromwell criticizing the legal system. She noted that many murderers "escaped through friends & money, & poor people for lesser facts are put to death', while lamenting that in prison many are treated "worse than dog" (9)

In 1653 George Fox was imprisoned in Carlisle for preaching with other leading Quakers including Hooton, James Nayler, and William Dewsbury. After speaking out in a church in Beckingham, Lincolnshire, in 1654, Hooton was imprisoned for five months, becoming the first Quaker to be punished in that county. She served a further three weeks in Lincoln in 1655 for "exhorting the people to repentance". Harsh treatment by a female gaoler prompted her to write once again to Cromwell condemning prison conditions. In 1660 Hooton was "back in Nottinghamshire where a man named Jackson, the minister for Selston, violently assaulted her, allegedly without provocation, while she was walking along the road." (10)

Fox always insisted that God called women to be preachers and evangelists just as he had traditionally called men. It has been estimated that ministry of women, made up 45% of the early Quaker movement. (11) Elizabeth Hooton became one of the Quakers most respected leaders. These women also raised important questions about overturning other traditional relationship between the sexes. Men began to argue that women preachers would lead to immorality. One critic complained that even conversing with women seduced and drew them away from their husbands. One observer claimed that the Quakers "hold a community of women and other men's wives and practice living upon one another too much." (12)

Charles II was restored to power in May 1660. Quakers feared increased persecution. In a letter to the king Margaret Fell was one of the first writers to articulate the Quaker philosophy of peace and non-resistance she declared that the Quakers aspire "to live peaceably with all men, And not to Act any thing against the King nor the peace of the Nation, by any plots, contrivances, insurrections, or carnal weapons to hurt or destroy either him or the Nation thereby, but to be obedient unto all just & lawful Commands". (13)

North America

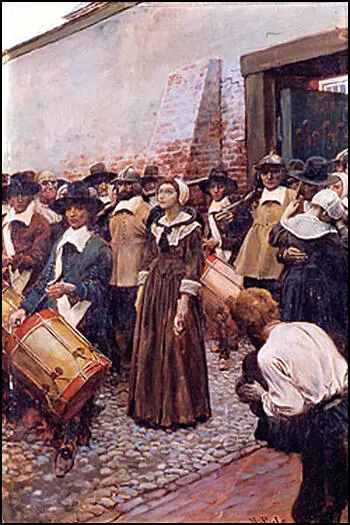

In 1661, after the death of her husband, Hooton travelled to America with a friend, Joanne Brooksup. They received a hostile reception when they arrived in Boston. John Endicott, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who issued judicial decisions banishing individuals who held religious views that did not accord well with those of the Puritans. He especially hated Quakers and the previous year he had ordered the execution of four of them including Mary Dyer. (14)

Hooton and Brooksup were spared this punishment but were driven for two days out into the wilderness and left to starve. They managed to make their way to Rhode Island, from where they obtained a passage to Barbados, before returning once again to Boston "to testify against the spirit of persecution there predominant" Arrested again they were put on board a ship for Virginia and eventually returned to England. (15)

Quaker Persecution

On 6 January, 1661, Thomas Venner and a group of fifty members of the Fifth Monarchists, attempted to overthrow the the seven-month-old regime of Charles II, by taking over St. Paul's Cathedral. A combined group of volunteers and regular forces had little difficulty in dealing with the rebels and they were either killed or captured. Venner and thirteen others were hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason. Their heads were stuck up on London Bridge as a warning to others who might attempt similar rebellious acts. (16)

Two days after Venner's execution Fox and eleven other Quakers issued what latter became known as the "Peace Testimony". The signers did not include militants such as Edward Burrough and Thomas Salthouse. The statement said it wanted to remove "the ground of jealously and suspicion" regarding "the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers." It then went on to argue: "We utterly deny all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatsoever; and this is our testimony to the whole world. The spirit of Christ, by which we are guided, is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we do certainly know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world." (17)

Despite this statement the Venner's Rising led to repressive legislation to suppress non-conformist sects. This included the Quakers. George Fox and other leaders were taking into custody. Margaret Fell wrote to the king asking for Fox to be released. She warned that "the people of God, called Quakers," had limited patience; they would "love, own, and honor the king, and these our present governors, so far as they do rule for God and his truth and do not impose anything upon people's consciences." (18)

Elizabeth Hooton also wrote to Charles II. In 1662 she handed letters to the king in St James's Park, causing a stir among bystanders because she did not kneel. Receiving no reply, she continued to harangue Charles and was, she recalled, "moved to go amongst them again at Whitehall in sack-cloth and ashes". Hooton eventually obtained a royal licence to settle in any of the American colonies, and sailed to Massachusetts with her daughter, Elizabeth. (19)

Hooton asked the Boston authorities for a house, a place for Quakers to meet, and land for a burial-ground, but was refused in spite of the king's recommendations. Hooton became a wandering preacher and was imprisoned briefly at Hampton and Dover. At Cambridge she was arrested and sent out into the wilderness on horseback. She eventually reached Rhode Island that was under the control of the more tolerant Roger Williams. However, she returned to Boston and soon afterwards she was whipped through three towns (Roxbury, Dedham, and Medfield) and cast out into the wilderness. After further imprisonment she was warned that she faced execution or branding should she ever return. Hooton now decided to return to England. (20)

Hooton once again became an itinerant preacher. In 1663 she suffered the distraint of three mares and other losses which made it very difficult for her to continue farming. In 1667 she wrote a letter condemning the Quaker missionary, John Perrot. He had refused to condemn James Nayler before travelling to France, Italy, Greece and Turkey. After spending long periods in prison he arrived back in England. Fox was concerned that Perrot was making a challenge for the leadership of the movement: "Perrot was accused of financial extravagance during his mission in the Mediterranean, and his writings, especially his poetry, were regarded as an offence to the principle of plainness; moreover, Fox and other prominent Quakers saw Perrot's stance on hats as vain and lacking in humility... his enthusiastic preaching, his growing popularity particularly with women Friends, and even his Rabbinic-like beard reminded them uncomfortably of Nayler. It was averred that he had taken on his ministerial role too soon, a point underlined when Perrot began to hold his own meetings in London which only helped to enhance his reputation as a schismatic." (21)

Missionary

In August 1671, Elizabeth Hooton, George Fox, James Lancaster and ten other Quakers left England to visit the colonies. One of the main reasons was to eradicate pockets of settlers who were supporters of John Perrot. Their ship arrived in Barbados on 3 October. Quakers were the second largest religious denomination on the island and they owned five meeting houses. They tended to own some of the largest plantations and depended for their success on slave labour. Quakers averaged twelve slaves per household. (22)

It was claimed that some Quakers who lived in Barbados, under the influence of Perrot, permitted men to wear hats when they prayed. Fox issued stern warnings about this and insisted they follow the "order of the gospel". He also condemned acts of sexual immorality. He told a meeting of women that men with the "evil custom" of "running after another women when married to one already" should be forced to break off their illicit relationships." (23)

Fox was keen to point out that Quakers supported slavery. He denied that Quakers promoted slave unrest and that meetings for slaves taught them "justice, sobriety, temperance, charity, and piety, and to be subject to their masters and governors," not prescriptions for insurrection. (24) As H. Larry Ingle points out: "In a colony, where potentially insubordinate blacks comprised two-thirds of the population, whose economic well-being rested squarely on slave labour, and whose social cohesion depended on black's submission to their white masters, this matter was more critical than the subtleties of theological beliefs." (25)

In his journal Fox claimed he exhorted the blacks "to be sober & to fear God and to Love their masters and mistresses, and to be faithful and diligent in their masters service & business & that then their masters & Overseers will love them and deal kindly & gently with them". The slaves were not to beat their wives, steal, drink, swear, lie, or commit fornication. Whites and blacks had the same path to heaven, and masters had a responsibility for religious training of their families. There was no mention of eventual freedom for the black servants. (26)

The party then travelled to Jamaica. Hooton was extremely ill at this time. James Lancaster recorded that she was weak and swollen and was unable to speak. Elizabeth Hooton died in February 1672. H. Larry Ingle has argued that Hooton has never received adequate recognition of the important role she played in the Quaker movement. The main reason is that she received no more than occasional mentions in George Fox's Journal (1694). "The Journal emphasizes those aspects of the movement most associated with Fox himself (the great open-air rallies and disputations) at the expense of others (the brilliantly planned and executed publicity drives and the co-ordinated tithe-strikes) in which he was less involved. It was also a product of the struggle against dissent within the movement, reflecting the period of its composition. Fox casually excluded from his narrative or played down the role of several people who had once occupied prominent positions in the movement.... Moreover, Fox never concedes, much less confesses, any errors on his part: here is a man always in the right, sure of himself and his role, and convinced beyond any human doubt that he will be victorious in the end." (27)

Primary Sources

(1) H. Larry Ingle, First Among Friends (1994)

Among one group of Baptists in Nottinghamshire, in the tiny village of Skegby just four miles west of Mansfield, Fox's message lodged in the soul of a forty-seven-year-old woman, Elizabeth Hooton, who remained one of his most committed disciples. Like Fox, Hooton had also decided that the Baptists were not upright enough for her; indeed, she had made public statements about their deceit, making her a known dissident even before Fox's arrival. At first her husband opposed her new direction, but soon he too joined Fox's movement. Thereafter regular meetings were convened in the Hooton household, and it became a major base of operation in the area...

One problem that threatened a dark stain indeed involved the place of women in the movement. Fox never backed down from his insistence that God called women to be preachers and evangelists just as he had traditionally called men. From the very first, when Elizabeth Hooton began to preach and prophesy, women had played an active role among the Children of the Light, and Margaret Fell's position called attention to this reality. Critics of the Quakers thus had an opening that was too good to miss, particularly when the specter of female equality of function raised troubling questions about overturning other traditional relationships between the sexes. The easiest target was, of course, the possibility of immorality among a group allowing women to preach.

(2) Caroline L. Leachman, Elizabeth Hooton : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September, 2004)

Hooton soon troubled the authorities with her preaching and her protestations against the corruption of the clergy and magistrates. Her first recorded imprisonment appears to have been in Derby about 1651 for reproving a minister. In 1652 she was imprisoned in York Castle for admonishing a minister and his congregation in Rotherham at the close of their worship. With other Quakers, including Mary Fisher and Thomas Aldam, she was a signatory to False Prophets and False Teachers (1652), a tract attacking paid ministry, written in the castle. Her experiences at York led her to write to Oliver Cromwell criticizing the legal system... In 1653 Fox was imprisoned in Carlisle for preaching with other leading Quakers including Hooton, James Nayler, and William Dewsbury. After delivering the Quaker message at a church in Beckingham, Lincolnshire, in 1654, Hooton was imprisoned for five months, becoming the first to suffer for Friends in that county. She served a further three weeks in Lincoln in 1655 for "exhorting the people to repentance"... In 1660 Hooton was back in Nottinghamshire where a man named Jackson, the minister for Selston, violently assaulted her, allegedly without provocation, while she was walking along the road.

Hooton's husband died on 30 June 1657. Four years later, in 1661, she travelled to America with Joanne Brooksup or Brooksop. Her son Samuel opposed the undertaking, but later supported her decision and eventually preached in America himself. Arriving at Boston, via Virginia, they were imprisoned by Governor Endicott and then driven for two days out into the wilderness and left to starve. They managed to make their way to Rhode Island, from where they obtained a passage to Barbados, before returning once again to Boston "to testify against the spirit of persecution there predominant". Apprehended by a constable, they were then put on board a ship for Virginia and eventually returned to England.