Thomas Venner

Thomas Venner was probably born in Littleham, Devon, in about 1608. By 1633 he had moved to London, where he worked as a cooper and became a member of the Coopers' Company. Venner emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts, in 1638 where he was allocated 40 acres. A juryman in 1638 and 1640, he married Alice and his son Thomas was born in 1641. The following year he served as constable. He spent time in Providence Island in the West Indies, but in 1644 he returned to America and settled in Boston. His wife gave birth to two more children, Hannah (b. February 1645) and Samuel (b. February 1650). Venner became a member of the artillery company in 1645 and in October 1648 he organized the coopers of Boston and Charlestown into a trading company. (1)

After the execution of Charles I on 30th January 1649, Venner returned to England. Following the English Civil War groups such as the Levellers, Diggers and the Fifth Monarchists began to demand political reforms. Venner became a Fifth Monarchist. (2) They argued that the king's death was a prophetic moment, signalling the coming of the new millennium and the reign of Christ and the saints on earth. This was as a result of their close reading of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel, in which the fall of the four earthly empires (Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman) would be followed by the rule of "King Jesus" and his saints. (3)

Thomas Venner and Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was opposed to these groups and their leaders such as John Lilburne were imprisoned. Soldiers continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed. (4)

Lockyer's funeral on Sunday 29th April, 1649, proved to be a dramatic reminder of the strength of the Leveller organization in London. "Starting from Smithfield in the afternoon, the procession wound slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the interment in New Churchyard. Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons - black for mourning and sea-green to publicize their Leveller allegiance. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous autumn." (5)

Fifth Monarchist's Rebellions

By 1655 Venner was employed as a master cooper in the Tower, but he was arrested in June and dismissed for allegedly discussing the possible assassination of Oliver Cromwell. (6) The government did not take him very seriously, for he was free by winter, when he participated in meetings with other Fifth Monarchists, including John Portman and Arthur Squibb, and republicans such as John Okey and the naval officer John Lawson. It is claimed that the men discussed A Healing Question (1656) that had been written by Henry Vane. The pamphlet argued for civil and religious liberty. (7)

It was the starting point for their discussions about possible joint political action, but they failed to achieve substantive agreement. Okey, Lawson, Portman, and others were arrested in the summer, and officials were searching for Venner. In early August he was holding meetings of his Fifth Monarchist congregation at Swan Alley, Coleman Street, London; copies of Englands Remembrancers, "urging the godly to elect proponents of the Good Old Cause to parliament, were distributed." (8)

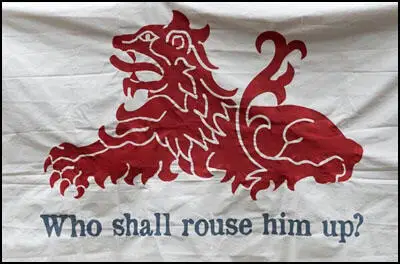

In April 1657 he planned a rising that was backed by a manifesto, a flag that depicted a red lion and the motto "Who shall rouse him up?" The rebels intended to rendezvous at Mile End Green and then march into East Anglia, where they expected many recruits to join them. Venner and about 25 other men were arrested in London before "their plans for a theocracy and government according to biblical lore had been put to much of a test." Venner was sent to prison again, without a trial, and by the time Charles II was restored to the throne he was free once more. "His zeal was undimmed, possibly because no one seemed to take him seriously enough to prosecute him for what were undoubtedly treasonous acts." (9)

Restoration

It has been claimed that Major General Thomas Harrison and John Carew were supporters of the Fifth Monarchists. (10) On the Restoration Harrison was an obvious target for the Royalists. Harrison refused to flee the country and was therefore like other Regicides arrested and brought to the Tower of London. At his trial in October 1660 he asserted that he had acted in the name of the parliament of England and by their authority. "Maybe I might be a little mistaken, but I did it all according to the best of my understanding, desiring to make the revealed will of God in his holy scriptures as a guide to me". (11)

Harrison claimed he had been acting on the authority of the House of Commons: Denzil Holles rejected this argument. "You do very well know that this that you did, this horrid, detestable act which you committed, could never be perfected by you till you had broken the Parliament. That House of Commons, which you say gave you authority, you know what yourself made of it when you pulled out the speaker; therefore do not make the Parliament to be the author of your black crimes." (12)

Harrison was found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. On 13th October 1660 he was taken on a sledge to Charing Cross, the place of his execution. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (13) Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves." (14)

Venner Rebellion

Venner responded to death of Harrison and the other Regicides by producing a new manifesto, A Door of Hope, that called his followers to arms, urging them not to sheath their swords until the monarchy had been destroyed. It called for an international crusade, financed by expropriated property, to defeat France, Spain, the Catholic states in Germany, and the papacy, and for a godly society free of poverty, taxation, primogeniture, and capital punishment for theft. (15)

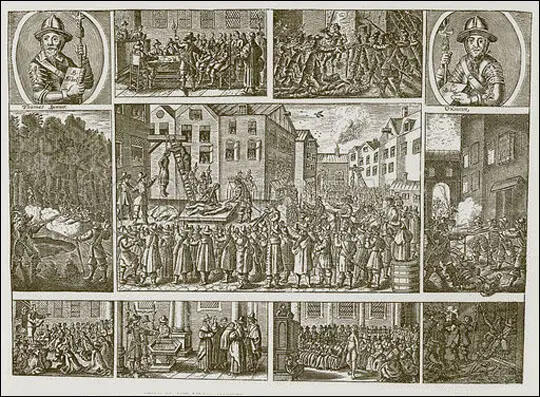

Venner and about 50 of his supporters carried flags emblazoned with King Jesus, and the "regicides' heads upon the gates" temporarily seized St Paul's, before retreating to Aldersgate. The rebels fought in a skirmish early on Wednesday morning near Leadenhall Street. Venner later claimed he had killed at least three of the approximately twenty loyalists who died. The Vennerites suffered comparable losses, and Venner himself sustained nineteen wounds. (16)

Arraigned at the Old Bailey on the 17th, he initially refused to plead, instead launching into a discourse on the Fifth Monarchy. After finally pleading not guilty, he admitted having participated in the insurrection, but not as leader, for that had been Jesus's role. (17) As Venner prepared to be hanged, drawn, and quartered before his meeting-house on 19 January 1661, he remained defiant, claiming to have acted "according to the best light I had, and according to the best understanding that the Scripture will afford". (18)

By 21 January thirteen of his compatriots had been executed, and the government demolished his meeting-house. Their heads were stuck up on London Bridge as a warning to others who might attempt similar rebellious acts. (19) As Richard L. Greaves has pointed out: If the revolt was pathetic and desperate, as some historians have suggested, it was also a manifestation of Venner's fierce conviction that Christ's people, their triumph assured, were literally to take the field against the forces of Antichrist. Resolute in his faith, Venner was a misguided millenarian zealot." (20)

Two days after Venner's execution George Fox and eleven other Quakers issued what latter became known as the "Peace Testimony". The signers did not include militants such as Edward Burrough and Thomas Salthouse. The statement said it wanted to remove "the ground of jealously and suspicion" regarding "the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers." It then went on to argue: "We utterly deny all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatsoever; and this is our testimony to the whole world. The spirit of Christ, by which we are guided, is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we do certainly know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world." (21)

Primary Sources

(1) Richard L. Greaves, Thomas Venner : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September, 2004)

Venner, Thomas (1608/9–1661), Fifth Monarchist, was probably born in Littleham, Devon. By 1633 he had moved to London, where he worked as a cooper and became a member of the Coopers' Company, probably in that year. Aged twenty-eight, he testified with the separatists Praisegod Barebone and Stephen More before the high court of admiralty in January 1637 regarding a shipment of wine to Virginia. He subsequently emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts, where he was admitted to its church on 25 February 1638 and became a freeman of the town the following month. A juryman in 1638 and 1640, he served as constable beginning in August 1642. Dissatisfied with life in Salem, he organized some of the settlers to move to Providence Island in the West Indies, but this endeavour apparently collapsed. Venner sold the 40 acres allocated to him in Salem and moved to Boston by 1644. With him were his wife, Alice (d. 1692), and son, Thomas, baptized at Salem in May 1641; he and Alice would have two more children in Boston, Hannah (b. February 1645) and Samuel (b. February 1650). Venner became a member of the artillery company in 1645, and in October 1648 he organized the coopers of Boston and Charlestown into a trading company.

Some time following the return of Venner and his family to London in October 1651, he embraced Fifth Monarchist tenets. By 1655 he was employed as a master cooper in the Tower, but he was arrested in June and dismissed for allegedly discussing Cromwell's assassination and plotting to blow up the Tower. The government did not take him very seriously, for he was free by winter, when he participated in meetings with other Fifth Monarchists, including John Portman and Arthur Squibb, and republicans such as John Okey and the naval officer John Lawson. Henry Vane's A Healing Question was the starting point for their discussions about possible joint political action, but they failed to achieve substantive agreement. Okey, Lawson, Portman, and others were arrested in the summer, and officials were searching for Venner. If he was detained, it was only briefly, for in early August he was holding meetings of his Fifth Monarchist congregation at Swan Alley, Coleman Street, London; copies of Englands Remembrancers, urging the godly to elect proponents of the Good Old Cause to parliament, were distributed. Apparently the members of the church, some of whom had been lured from John Rogers's congregation, were primarily young men and apprentices. During the winter of 1656–7 Venner planned an insurrection, organizing five groups of twenty-five members each, with only one person in each cell knowing details about the other units. Venner and Portman discussed possible co-operation, but Rogers, Thomas Harrison, and John Carew were opposed, while Christopher Feake and Livewell Chapman were apparently not approached. Venner's people obtained maps, telescopes, horses, weapons, and armour, and his son-in-law, William Medley, drafted a manifesto, A Standard Set Up. It proclaimed the saints' intention to establish theocratic government featuring a sanhedrin and a governing council, each elected by members of gathered churches, and biblically based laws. Land tenures would be reformed and copyhold abolished. The Vennerites intended to confiscate their enemies' property, depositing some of it in a public treasury to support God's work and distributing the rest equally among themselves. Proposed legal reforms, including a hierarchy of courts, beginning with monthly ones in market towns, were aimed at ending law as an instrument of social oppression; judges, like all other officials, would be chosen by the saints alone. The rebels intended to rendezvous at Mile End Green and then march into East Anglia, where they expected many recruits to join them. Venner asked his female followers to distribute copies of the manifesto.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)