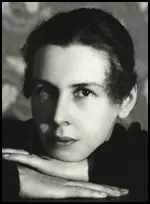

Lydia Lopokova

Lydia Lopokova was born in St. Petersburg on 21st October 1892. Her father, worked as the chief usher at the Alexandrinsky Theatre. Her mother, Rosalia Constanza Karlovna Douglas, was the descendent of a Scottish engineer and had a strong interest in dancing.

Lopokova trained at the Imperial Ballet School and soon came under the influence of Mikhail Fokine. According to Margot Fonteyn: "Although a demi-caractère dancer, she could also shine in the purely classical roles because of her strong technique, extreme lightness in jumping, and stylistic sensitivity." Lopokova came to the attention of Sergei Diaghilev and promoted her as a future star and in 1910 she joined the Ballets Russes Company on its European tour. This included appearing with Vaslav Nijinsky in Carnaval.

In 1912 she was approached by an American promoter and she accepted an offer of ₤16,000 per month to appear in The Lady of the Slipper at the Globe Theatre. It opened on the 28th October, 1912 and ran for 232 performances. This was followed by Just Herself at the Playhouse Theatre (December, 1914 - January 1915), Fads and Fancies at the Knickerbocker Theatre (March, 1915 - April, 1915) and the Age of Reason at the Bandbox Theatre (October, 1915 - May 1916).

The New York Tribune theatre critic, Heywood Broun, was very impressed when he saw Lopokova in The Antick, a play by Percy MacKaye. His review the next morning showed how much he enjoyed her performance: "We regret now wasted adjectives and we pine for every superlative with which we have lightly parted. All words denoting, connoting or appertaining in any way to charm we would bestow upon Lydia Lopokova... She is the most charming young person who has trod the stage in New York this season. But she did not tread. She did not even walk. She skipped, she danced, she pranced, and, like as not, she never touched the stage. Or so it seemed."

Broun invited Lopokova out to dinner. Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) has pointed out: "Thereafter Heywood pursued a headlong courtship, took her walking afternoons in Central Park, to supper after the nightly performance. They were the original odd couple: the tiny sophisticated Russian ballerina and the hulking Broun in his raccoon coat and black hat. Other admirers of the Russian girl couldn't understand what she saw in the ungainly Broun in eternal dishabille, but women had and would always find him attractive in a teddy-bear sort of way. He appealed to their maternal instincts. The first thought any woman had on glimpsing Broun was that he needed taking care of - and reforming. His tousled hair and his off-center necktie, his slightly forlorn air, his generally unkempt condition (despite his mother's continuing efforts) recommended even to a Russian dancer-actress intent on her own career the need for someone to take Heywood in hand."

Lopokova accepted Broun's proposal of marriage. He told his friend Franklin Pierce Adams, who reported in the New York Evening Mail: "Heywood Broun, the critic, I hear hath become engaged to Mistress Lydia Lopokova, the pretty play actress and dancer. He did introduce her to me last night and she seemed a merry elf." However, the relationship was not to last as soon after she fell in love with Randolfo Barocchi who she did marry. She later recalled "my professional career involved me in a whirl of excitement. I felt I did not want to be tied up to Heywood - so I broke it off, hurting him very much at the time, I am sorry to say."

In 1916, Lopokova returned to ballet dancing when she rejoined the Ballets Russes Company. That year she appeared with Vaslav Nijinsky in New York City and London. She was highly praised for the roles created for her by Léonide Massine in The Good-Humoured Ladies (1917–18) and La Boutique Fantasque (1919). During this period she came to the attention of John Maynard Keynes. At first he was unimpressed: "she's a rotten dancer - she has such a stiff bottom". When he saw her again towards the end of 1921 in other Sergei Diaghilev ballets, including The Sleeping Princess, he fell deeply in love with her and they began a romantic relationship.

A member of the Bloomsbury Group, Keynes introduced Lopokova to his friends. This included Virgina Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, and Duncan Grant. They did not always make her feel welcome. According to Margot Fonteyn: "When Keynes began to think of marriage, some of his friends were filled with foreboding. They tended to find Lopokova bird-brained. In reality she was intelligent, wise, and witty, but not intellectual... She artfully used, and intentionally misused, English to unexpectedly comic and often outrageous effect. Keynes was constantly amused and enchanted."

Quentin Bell claimed that Virginia Woolf liked Lopokova. "Lydia as a friend, Lydia as a visiting bird hopping gaily from twig to twig was, Virginia thought, very delightful. She was pretty, high-spirited, a comic, a charmer and extremely well-disposed. In that gay, peripatetic capacity she was altogether irreproachable. But how, without two solid ideas to rub together, could she fail to destroy the intellectual comforts of Maynard Keynes's friends, and indeed of Maynard himself?" Lytton Strachey described her as a "half-witted canary".

Hermione Lee, the author of Virginia Woolf (1996) claims that Lydia was ridiculed by Virginia for her effusive, naive, foreign eccentricities, and even more by Vaanessa, whose intimacy with Maynard she threatened.... Lydia's high spirits and passion for Maynard overrode the hostility of his set. But when Virginia drew on her for Rezia in Mrs Dalloway (so closely that she caught herself calling Lydia 'rezia') she made a touching, attractive character."

Vanessa Bell, like everyone else, was enchanted by Lydia, until Keynes announced he intended to marry her. Vanessa wrote to Keynes: "Clive (Bell) says he thinks it is impossible for any one of us... to introduce a new wife or husband into the existing circle... We feel that no one can come into the sort of intimate society we have without altering it." Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994) pointed out that Duncan Grant, his former lover, had good reason to object to the proposed marriage: "Perhaps Duncan Grant had some excuse for resenting the emergence of a second great love into Maynard's life. But it was the others who were really malicious. As Maynard's mistress, Lydia had added something childlike and bizarre to Bloomsbury - she was a more welcome visitor than Clive's over-chic mistress Mary Hutchinson. But don't marry her... . If he did so Lydia would give up her dancing, Vanessa warned, become expensive, and soon bore him dreadfully. But what Vanessa and the other Charlestonians chiefly minded was Lydia's effect as Maynard's wife on Bloomsbury itself. Living a quarter-of-a-mile from Charleston at Tilton House on the edge of the South Downs, she would sweep in and stop Vanessa painting - and these interruptions were always so scatterbrained!"

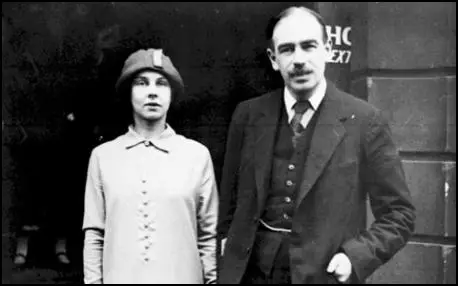

Lopokova married John Maynard Keynes on 4th August 1925 (the year of her divorce from Randolfo Barocchi) at St Pancras Registry Office. The wedding received a considerable amount of publicity. For example, Vogue Magazine included a full-page picture with the caption: "The marriage of the most brilliant of English economists with the most popular of Russian dancers makes a delightful symbol of the mutual dependence upon each other of art and science."

They visited the Soviet Union on their honeymoon. His biographer, Alexander Cairncross, has argued: "The marriage proved a great success and was a turning point in Keynes's life. Lopokova had gifts to which Bloomsbury was blind and she had a firm hold on his affections. When apart they wrote every day and she took charge of him in his illnesses and in wartime, when his energies had to be carefully husbanded. The couple had no children." The couple lived at 46 Gordon Square and Tilton House near Firle in East Sussex.

Virginia Woolf visited the couple at Tilton House on 3rd September 1927 with J. T. Sheppard: "We picked the bones of Maynard's grouse of which there were three to eleven people. This stinginess is a constant source of delight to Nessa - her eyes gleamed as the bones went round. We had a brilliant entertainment afterwards... Maynard was crapulous and obscene beyond words, lifting his left leg and singing a song about women. Lydia was Queen Victoria dancing to a bust of Albert."

Margot Fonteyn has pointed out: "Lopokova continued to dance and act intermittently, playing Ibsen, Molière, and Shakespeare, albeit with her charming Russian accent; and she helped the burgeoning British ballet tremendously. But from when Keynes suffered his first serious illness in 1937... the total dedication she had never quite mustered for her career came to flower. She was a devoted wife, forsaking all interests save her husband's health and work while entertaining him and their friends with her unpredictable remarks."

Alexander Cairncross has argued: "From the summer of 1936 Keynes was affected by a prolonged spell of illness, beginning with chest pains and breathlessness. After a complete collapse in May 1937 heart trouble was diagnosed and a complete rest prescribed. He gradually improved, and was writing occasional letters and even the odd article by July 1937. But when he returned to London and Tilton in late September he still needed Lydia's constant care to prevent overexcitement and overwork, and he continued to need it for the rest of his life." John Maynard Keynes died on 21st April 1946.

Lydia Lopokova, Lady Keynes, died at Threeways Nursing Home, Seaford on 8th June 1981.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard O'Connor, Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975)

Thereafter Heywood pursued a headlong courtship, took her walking afternoons in Central Park, to supper after the nightly performance. They were the original odd couple: the tiny sophisticated Russian ballerina and the hulking Broun in his raccoon coat and black hat. Other admirers of the Russian girl couldn't understand what she saw in the ungainly Broun in eternal dishabille, but women had and would always find him attractive in a teddy-bear sort of way. He appealed to their maternal instincts. The first thought any woman had on glimpsing Broun was that he needed taking care of - and reforming. His tousled hair and his off-center necktie, his slightly forlorn air, his generally unkempt condition (despite his mother's continuing efforts) recommended even to a Russian dancer-actress intent on her own career the need for someone to take Heywood in hand.

(2) Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey (1994)

Perhaps Duncan Grant had some excuse for resenting the emergence of a second great love into Maynard's life. But it was the others who were really malicious. As Maynard's mistress, Lydia had added something childlike and bizarre to Bloomsbury - she was a more welcome visitor than Clive's over-chic mistress Mary Hutchinson. But don't marry her, Vanessa had instructed Maynard (1st January 1922). If he did so Lydia would give up her dancing, Vanessa warned, become expensive, and soon bore him dreadfully. But what Vanessa and the other Charlestonians chiefly minded was Lydia's effect as Maynard's wife on Bloomsbury itself. Living a quarter-of-a-mile from Charleston at Tilton House on the edge of the South Downs, she would sweep in and stop Vanessa painting - and these interruptions were always so scatterbrained!

(3) Victoria Glendinning, Leonard Woolf: A Life (2006)

Maynard Keynes (who of course had a motor car), after he married Lydia Lopokova in 1925 acquired Tilton farmhouse, just up the lane from Charleston, as a weekend and holiday house. Maynard, the richest of the friends, could afford to make Tilton, already more imposing than the average farmhouse, comfortable to a degree hitherto unknown to either Charleston or Rodmell - electric light, central heating, and every modern convenience. For this he was both mocked and envied.