Alex Tudor-Hart

Alex Tudor Hart studied at Cambridge University where he was a student of John Maynard Keynes. Later he studied medicine in London.

Alex Tudor Hart joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and went to Austria to study orthopaedics under the famous surgeon Professor Boehler. Later, he found work at the British consulate in the city.

In 1925 Tudor Hart met the photographer, Edith Suschitzky. Her biographer, Amanda Hopkinson, has pointed out that Edith "was remembered by those who knew her in her youth as immensely vivacious, amusing, curious, and gifted". At the time she was studying photography under Walter Peterhans at the Bauhaus in Dessau. She was also involved in left-wing politics and after Adolf Hitler came to power she was arrested as a "communist sympathiser".

Alex Tudor Hart & Edith Suschitzky

They married at the British consulate in Vienna in 1933. They moved to England and Alex became a general practitioner (GP) in London and Edith established a photographic studio in Brixton. In her photographs she documented a great many of her husband's patients and their children, living conditions, home and working lives.

Edith Tudor Hart had been working with the NKVD since 1929. Her main contact was Litzi Friedmann who had also born in Vienna and had married an Englishman, Kim Philby. In January 1934 Arnold Deutsch, one of NKVD's agents, was sent to London. As a cover for his spying activities he did post-graduate work at London University. In May he made contact with Edith and Litzi. They discussed the recruitment of Soviet spies. Litzi suggested her husband. "According to her report on Philby's file, through her own contacts with the Austrian underground Tudor Hart ran a swift check and, when this proved positive, Deutsch immediately recommended... that he pre-empt the standard operating procedure by authorizing a preliminary personal sounding out of Philby."

Recruits Kim Philby

Philby later recorded that in June 1934. "Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a 'man of decisive importance'. I questioned her about it but she would give me no details. The rendezvous took place in Regents Park. The man described himself as Otto. I discovered much later from a photograph in MI5 files that the name he went by was Arnold Deutsch. I think that he was of Czech origin; about 5ft 7in, stout, with blue eyes and light curly hair. Though a convinced Communist, he had a strong humanistic streak. He hated London, adored Paris, and spoke of it with deeply loving affection. He was a man of considerable cultural background."

Deutsch asked Philby if he was willing to spy for the Soviet Union: "Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background and possibilities could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathiser... I accepted. His first instructions were that both Lizzy and I should break off as quickly as possible all personal contact with our Communist friends." It is claimed by Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Philby became the first of "the ablest group of British agents ever recruited by a foreign intelligence service."

Rhondda Valley

Alex Tudor Hart became a doctor in the Rhondda Valley in Wales. Edith Tudor Hart continued to take photographs of her husband's patients. Duncan Forbes has argued that she saw the camera as a political weapon. Her recurring themes were child welfare, unemployment and homelessness. “She liked the detail that came with a medium-format Rolleiflex camera. And seeing the world from waist height, which is where you hold those cameras, meant she was able to communicate better with her subjects. Her face wasn’t hidden. What intrigued me about her was what a good picture maker she was, bridging the divide between a documentary style and something more pictorial." Forbes adds that she took photographs “through windows to emphasise her voyeurism, and limit the sentimentality”.

In 1935 Edith Tudor Hart contributed to the Artists' International Association (AIA) exhibition, Artists against Fascism and Against War. She also had some of her photographs published in Picture Post, Daily Chronicle and Lilliput Magazine. She wrote about the political implications of her photography: "In the hands of the person who uses it with feeling and imagination, the camera becomes very much more than the means of earning a living, it becomes a vital factor in recording and influencing the life of the people and in promoting human understanding." Edith gave birth to a son, Thomas, in 1936. He suffered from autism.

Edith Tudor Hart continued to work with the NKVD. In a letter dated 8th October 1936 stated: "Through EDITH (Edith Tudor Hart) we obtained SOHNCHEN (Philby). In the attached report you will find details of a second SOHNCHEN who, in all probability, offers even greater possibilities than the first. EDITH is of the opinion that he is more promising than SOHNCHEN. From the report you will see that he has very definite possibilities. We must make haste with these people before they start being active in university life." The potential recruit was Anthony Blunt.

Spanish Civil War

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Tudor Hart decided that he must contribute to the war against fascism. In December 1936 he joined the British Medical Aid Unit. When he arrived in Spain André Marty appointed him to the rank of major.

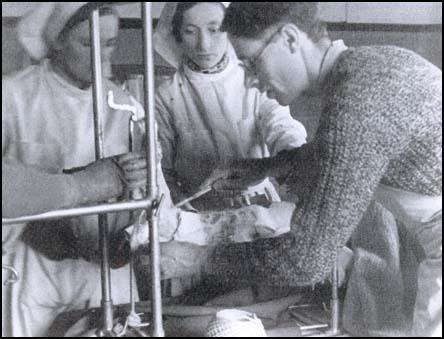

Dr. Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, who was head of the British Medical Aid Unit, later wrote: "Tudor-Hart was a sensible man and after one attempt at exercising his senior rank in an area in which he lacked competence (trying to lead a convoy while losing his way near the fascist lines), he restricted himself to the field in which he was superb - traumatic surgery. He saved hundreds of lives and thousands of limbs, and I am proud to have worked with him."

Tudor Hart returned to Wales in October 1938. According to her biographer, Amanda Hopkinson, by the "time he returned at its end Edith had to accept that their marriage was effectively over." His son, Julian Tudor Hart, became a general practitioner in Glyncorrwg, a mining village in the Rhondda Valley. In later years he enjoyed a relationship with Innes Herdan.

Dr. Alex Tudor Hart died in 1992.

Primary Sources

(1) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

As I was told on my return from London, Marty was most happy to accept the Spanish Medical Aid Unit as an integral part of the Medical Service of the International Brigade. Dr Neumann, the IB/HQ medical staff-officer indicated that my news and messages from the Spanish Medical Aid Committee should await a subsequent general meeting of the British group that he was arranging. That would be the appropriate moment to present to Comrade Marty the messages that I had brought with me. Dr Neuman said that André Marty was arranging all the necessary moves to ensure our getting to work with as little delay as possible. It was only very much later that I came to see why we had been the subject of such special consideration. Thora thought that I should perhaps open my belt and produce Harry Pollit's little bit of silk in order to secure a proper meeting with André Marty about the future of our whole Grañen group. Surprise, surprise - the very next morning the belt had gone - but nothing else had been stolen from our room. We did not so much regret the inevitable decision to leave well alone; we resented more the way it had been forced. We were after all going where we had wanted to go - into the crucial front of the war and into the International Brigade.

The general meeting came in a day or two. It was not André Marty but Colonel Domanski-Dubois, PMO of the 35th Division, who presided. Later I got to know him well and can see him to this day with his little smile and firm but somehow comforting manner. He was to give his life in the Aragon offensive of August 1937. For him the meeting was called to induct a group of newly recruited personnel into his Division and to give them their assignments. We were going as a Unit into the 14th (French speaking) International Brigade. He had brought with him all that he needed, namely the badges of rank for the new officers. This he would not have been able to do without prior briefing about the persons concerned. In a genial, informal way he put into Tudor Hart's hands the insignia of a Major, into Archie Cochrane's that of a Captain and into mine the single stripe of a sub-lieutenant, saying, "C'est tous qui me reste" Externally Tudor Hart did not register surprise; Cochrane, who was, like me, a. medical student and who had worked happily with me in Grañen was visibly disconcerted. We had worked together very easily in Grañen, and he had accepted without second thoughts the fact of my being in charge - a seniority that had well ante-dated his own arrival. As the Spanish Medical Aid Administrator, I had been responsible for the Unit in all but the strictly medical sense.

I realised that I could only roll with the punches in this competently managed mini-coup. Hart, in contrast to myself, did not know a word of Spanish. Someone would have to see to the daily running of the Unit (I had, after all, played a major part in turning it into an operational entity) while Hart worked as a surgeon. So far as Thora and myself were concerned, all that mattered was that the work should go on efficiently. In fact everything sorted itself out surprisingly quickly. Tudor-Hart was a sensible man and after one attempt at exercising his senior rank in an area in which he lacked competence (trying to lead a convoy while losing his way near the fascist lines), he restricted himself to the field in which he was superb - traumatic surgery. He saved hundreds of lives and thousands of limbs, and I am proud to have worked with him. We were attached to the 14th Brigade which was very largely French. Bit by bit I eventually pieced together the reasons for the very special consideration being shown to our Unit and for the manner of our assignment, some aspects of which only became clear to me very much later.

(2) Nigel Farndale, The Daily Telegraph (6th March 2013)

Being a Soviet agent doesn’t seem to have come naturally to the photographer Edith Tudor-Hart (née Suschitzky). For one thing she used the code name “Edith”, which was not subtle. For another, when she moved to London from her native Vienna in 1933 she liked to attend and photograph demonstrations led by the Communist Party of Great Britain.

She was, nevertheless, successful in one important regard: she is thought to have recruited Kim Philby, one of the Cambridge Five.

As a photographer working in the period her success was limited as well, at least in terms of her influence. It wasn’t that Tudor-Hart wasn’t innovative – she was, breaking the mould of static, studio-based portraits of children by introducing a more naturalistic style which showed them in their own environments, such as her photograph of children being treated for rickets using ultraviolet light. It was more that because Special Branch had her under surveillance (doing so until her death, in 1963), the Ministry of Information blacklisted her work and Fleet Street followed its lead.

Yet her work has since become significant and she is now the subject of a major exhibition at the National Galleries of Scotland. The photographs have been printed from her negative archive, which was donated by her family in 2004.

But because she destroyed her negative lists when Philby was first arrested, not all the figures in the photographs are identifiable. “She seems to have had a nervous breakdown when Philby was arrested,” Duncan Forbes, the exhibition’s curator, says. “But it wasn’t until Anthony Blunt’s confession in 1964 that she was really dropped in it.”

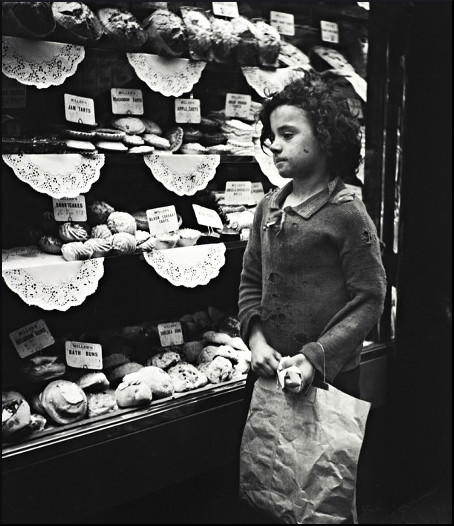

Tudor-Hart’s work had a strong social message, and she saw the camera as a political weapon. Her documentary projects took her from street markets in London’s East End to the slum housing areas of Tyneside and south Wales. Her recurring themes were child welfare, unemployment and homelessness.Her most popular image from the Thirties was Child Staring into Bakery Window, taken in Whitechapel, London. The juxtaposition of the plenitude of the bakery window with the dishevelled and hungry child emphasised the gap between rich and poor, and it was reproduced in a number of socialist propaganda pamphlets. It also reflected her preference for strong contrasts of black and white.

“She liked the detail that came with a medium-format Rolleiflex camera,” Forbes says. “And seeing the world from waist height, which is where you hold those cameras, meant she was able to communicate better with her subjects. Her face wasn’t hidden. What intrigued me about her was what a good picture maker she was, bridging the divide between a documentary style and something more pictorial.

One of Tudor-Hart’s “signature shots”, says Forbes, was of diagonal steel structures plunging into space. Mostly, though, she liked to photograph children on the streets and families in their homes, shooting them “through windows to emphasise her voyeurism, and limit the sentimentality”.

Had she not been arrested in Vienna in 1933 – for being a Communist sympathiser – she would probably have remained there. Instead she escaped imprisonment by marrying an English doctor and was exiled to London. “When she moved from Vienna to Britain she moved away from Bauhaus-style social realism to a more emotional identification with the figure in the picture,” Forbes says. “Her work became more direct and affecting. It can’t have been easy being a German-speaking émigré in wartime Britain. I think the move meant her life became a struggle.”