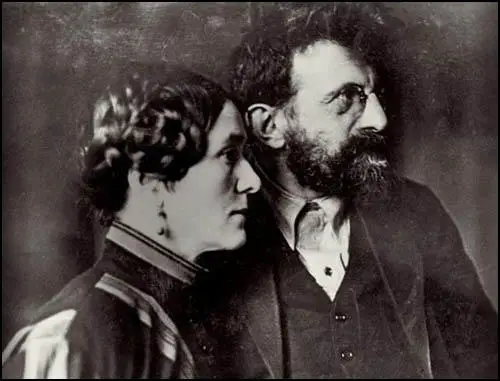

Zenzl Mühsam

Kreszentia (Zenzl) Elfinger, the fifth child of Augustin Elfinger, an innkeeper, was born in Haslach, Lower Bavaria, on 28th July, 1884. Her mother, Kreszentia Elfinger, died when she was eight years old and she endured extreme poverty in her childhood. At the age of sixteen she moved to Munich and two years later gave birth to a son, Siegfried, outside of wedlock. Unable to provide for her son, he grew up with relatives. (1)

In 1909 she began living with the artist, Ludwig Engler. She met Erich Mühsam in 1913. Mühsam led a very promiscuous life and was seen as one of the leaders of the free love movement. He wrote in his diary on 24th December, 1914: "This morning, when she sat at my bed, I realized how dear she is to me. She comes close to what I most long for in a lover: a substitute for my mother. I can put my head in her lap and let her caress me quietly for hours. I don't feel the same with anyone else. Her love is extremely important to me, and I have to thank her more in these hard times than I sometimes realize myself. Maybe I can return some of this one day!" (2)

The couple were married nine months later on 15th September, 1915. In 1917 Zenzl's son, Siegfried, went to live with them in Munich. Mühsam was an anarchist who was involved in protests against the First World War. As a result of his anti-war activities, Mühsam was banished from Munich on 24th April 1918, to a small Bavarian town of Traunstein. Mühsam desperately tried to organize coordinated resistance, but like others, failed. (3).

On 28th October, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany. (4)

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a Council Republic. Eisner's program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. Mühsam immediately returned to Munich to take part in the revolution. (5)

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (6)

Erich Mühsam was arrested and sentenced to fifteen years of confinement in a fortress. A few weeks later, the Weimar Republic was established, giving Germany a parliamentarian constitution. Gabriel Kuhn has argued: "Being confined in a fortress - a sentence usually reserved for political dissidents - meant certain privileges compared to the general prison population, most notably the opening of cells for communal meetings and activities during the day, but it also meant increased harassment, reaching from the confiscation of papers and diaries to punishments like isolation and food deprivation. Mühsam's health deteriorated drastically during those years." (7)

While in prison Mühsam briefly joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He explained in a letter to a friend, Martin Andersen Nexø: "I recently joined the Communist Party - of course not to follow the party line, but to be able to work against it from the inside." (8) He also praised Lenin and the Bolsheviks but left the KPD when he heard about how the anarchists were being treated in Russia. (9)

Mühsam was released from prison on 20th December, 1924. He was greeted by a large gathering of sympathizers when he arrived in Berlin. The scene was later described by the journalist, Bruno Frei: "Thanks to my press card I was able to get past the police barriers. Helmet-wearing security forces, both on foot and on horses, had sealed off the station. On the square in front of it, there were several hundred, maybe a thousand workers and youths with flags and banners. Their republican deed: to greet Erich Mühsam! When the express train from Munich arrived, a few youngsters managed to make their way into the arrival hall. Mühsam stepped out of the train in obvious pain, accompanied by his wife Zenzl. The young workers lifted him on their shoulders.... Mühsam fought back tears and thanked the comrades. Someone started to sing The Internationale. At that very moment, the helmet-wearing mob attacked the people who had gathered around Mühsam. They yelled at them, pushed them, and hit them with batons. The comrades resisted courageously, though, protected Mühsam, and led him outside. Unfortunately, the police had already begun to chase the workers from the square.... Many were arrested and wounded." (10)

After Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, Mühsam campaigned against the Nazi Party. He was arrested on 28th February, 1934 and was sent to a concentration camp in Oranienburg. His friend, Alexander Berkman, published details of his predicament: "I received a note from Germany yesterday. Erich Mühsam, the idealist, revolutionary, and Jew, represents everything that Hitler and his followers hate. They are attempting to destroy cultural and progressive life in Germany by destroying him. Mühsam became a particular object of Hitler's scorn because of his outstanding role in the Munich Revolution, alongside men like Landauer, Levine, and Toller." (11)

A fellow prisoner later recalled how Mühsam was regularly beaten: "Erich staggered, tripped over a bank, and fell on some straw mattresses. The wardens jumped after him, striking more blows. We stood still, clenching our fists and grinding our teeth, condemned to watch. We knew from experience that the slightest sign of resistance would send us to the hole for fourteen days or straight to the medical ward. Finally, the wardens pulled Erich up again and taunted him... They hit Erich again with their fists. He fell back onto the straw mattresses, the wardens followed and continued to hit and kick him." (12)

Another prisoner, John Stone, described how Erich Mühsam was murdered on 10th July, 1934: "In the evening, Mühsam was ordered to see the camp's commanders. When he returned, he said, They want me to hang myself - but I will not do them the favor. We went to bed at 8 p.m., as usual. At 9 p.m., they called Mühsam from his cell. This was the last time we saw him alive. It was clear that something out of the ordinary was happening. We were not allowed to go to the latrines in the yard that night. The next morning, we understood why: we found Mühsam's battered corpse there, dangling from a rope tied to a wooden bar. Obviously, the scene was supposed to look like a suicide. But it wasn't. If a man hangs himself, his legs are stretched because of the weight, and his tongue sticks out of his mouth. Mühsam's body didn't show any of these signs. His legs were bent. Furthermore, the rope was attached to the bar by an advanced bowline knot. Mühsam knew nothing about these things and would have been unable to tie it. Finally, the body showed clear indications of recent abuse. Mühsam had been beaten to death before he was hanged." (13)

Zenzl Mühsam confirmed the death of her husband to his friend, Rudolf Rocker: "I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured. I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this? I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me." (14)

Zenzl Mühsam left Berlin on 14th July, 1934. She travelled to Prague with her nephew Joseph Elfinger, whose father had been sent to Dachau Concentration Camp. In January 1935, she published The Ordeal of Erich Mühsam, in Moscow. The Nazi government reacted to this publication by stripping her of her German citizenship. Zenzl relocated from Berlin to Dresden, relatively close to the German border with Czechoslovakia. After Dorothy Thompson warned her that she was about to be arrested on 15th July 1934, she moved to Prague before travelling to Moscow on 8th August, 1935. (15)

Joseph Stalin, treated Sergey Kirov like a son, tried to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé. Kirov had several advantages over Stalin, "his closeness to the masses, his tremendous energy, his oratorical talent". Whereas, Stalin "nasty, suspicious, cruel, and power-hungry, Stalin could not abide brilliant and independent people around him." (16)

According to Alexander Orlov, who had been told this by Genrikh Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die. Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin. (17)

After the assassination of Kirov, Zenzl Mühsam was arrested as a supporter of Leon Trotsky. According to Victor Kravchenko: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks." (18)

Zenzl arrest was based on contacts with Erich Wollenberg and on correspondence with foreign anarchists. She spent four months in the prisons of Ljubjanka and Butyrka, before being released on 8th October, as a result of an international campaign on her behalf, supported by prominent figures such as Thomas Mann, Rudolf Rocker, André Gide, Harry Wilde and Ruth Osterreich. Zenzl returned to Moscow and on 13th June, 1937, she sold her husband's papers to the Maxim Gorky Institute. (19)

In the summer of 1938 Zenzl applied for a visa to the United States. This was rejected and she was rearrested. On 16th September, 1939, she was sentenced to eight years of hard labour for "abusing the Soviet Union's hospitality, and for participating in a counter-revolutionary organization and agitation". She spent the Second World War in Camp No.III in Yavas. Zenzl was released in November 1946 and exiled to the Novosibirsk district in Siberia.

Zenzl Mühsam worked at a children's home in Ivanovo. In February 1949 she was arrested by the NKVD and accused of belonging to an "anti-Soviet Trotskyist organization". Rudolf Rocker mounted an international campaign to get her released: "Why Zenzl Mühsam has been kept in Russian captivity for thirteen years - a time that not even eternity can give back to her - remains incomprehensible. It is possible that she was only used as a propaganda tool from the beginning; as a mere means of taking possession of Erich Mühsam's papers. It is also possible that she got to know too much about the inner workings of the NKVD and that the government considered it dangerous to let her return to Prague. Shortly after her arrival in Moscow, the era of terror began. If this was the case, then she was neutralized to protect the interests of the state - a purpose for which no means are despicable enough. A human life counts for nothing in a totalitarian police state like Russia." (20)

Zenzl was released but was not allowed to return to the children's home in Ivanovo until after the death of Joseph Stalin. On 13th March, 1955, she was given permission to live in East Berlin. She was provided with an apartment and a pension under the condition that she did not speak about her experiences in the Soviet Union. In a letter she sent to her friends in the United States she said that Bertolt Brecht was especially kind to her. On 22nd July, 1959, a military tribunal declared the 1936 and 1938 accusations levied against Zenzl unjust. (21)

Zenzl Mühsam died of lung cancer on 10th March, 1962.

Primary Sources

(1) Erich Mühsam, diary entry (24th December, 1914)

This morning, when she sat at my bed, I realized how dear she is to me. She comes close to what I most long for in a lover: a substitute for my mother. I can put my head in her lap and let her caress me quietly for hours. I don't feel the same with anyone else. Her love is extremely important to me, and I have to thank her more in these hard times than I sometimes realize myself. Maybe I can return some of this one day!

(2) Zenzl Mühsam, letter to Rudolf Rocker (31st July, 1934)

I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured.

I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this?

I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me.

(3) Rudolf Rocker, Appeal to the Conscience of the World (1949)

Why Zenzl Mühsam has been kept in Russian captivity for thirteen years - a time that not even eternity can give back to her - remains incomprehensible. It is possible that she was only used as a propaganda tool from the beginning; as a mere means of taking possession of Erich Mühsam's papers. It is also possible that she got to know too much about the inner workings of the NKVD and that the government considered it dangerous to let her return to Prague. Shortly after her arrival in Moscow, the era of terror began. If this was the case, then she was neutralized to protect the interests of the state - a purpose for which no means are despicable enough. A human life counts for nothing in a totalitarian police state like Russia.

It is pointless to engage in speculation, especially since the exact circumstances are not very important. The fact is that a disgraceful crime has been committed. Even the most unscrupulous criminal would hardly dare to touch this woman, who has already experienced so much suffering.

It is in doubt whether we can win her freedom and help her settle in a neutral country to live the rest of her abused life in peace. Maybe it would be possible if we were dealing with a different state. In my long life, I have participated in a number of international protest movements, and I recall with deep satisfaction powerful campaigns like the one to liberate the victims of Montjuich." At the time, the outrage in all countries was strong enough to force the Spanish inquisitors to let

their innocent victims go free. But people still had a feeling of personal dignity and a respect for human life then, something that the blind masses have lost today.

Still, now that the case of Zenzl Mühsam has finally entered public consciousness, we must use all the means we have to stir up the conscience of the world once again. This is one of the most ruthless crimes that have ever been committed by t hose in power against a human being who has already been kicked to the ground.

Zenzl Mühsam has become the symbol of abused humanity. This simple woman, a woman from the midst of the people, personifies the gruesome fate of hundreds of thousands of hapless human beings who slowly go under in the NKVD's dungeons and labor camps, and whose cries fade away in a world that does not care-like cries in the desert...

The terrible crime that was committed by the hangmen of the Third Reich against Erich Mühsam was an act of brutal rawness and of unspeakable barbarism. But I dare say that the outrageous treatment that his unfortunate wife has been experiencing in Russia for the last thirteen years is even worse, because it has been covered up by bottomless hypocrisy and infamous lies, intentionally misleading the public. While commemorative plaques are erected for Erich Mühsam in Germany's Russian sector and streets and squares are named after him, his widow is slowly tortured to death. It would be hard to take hypocrisy and mendacity any further.