Karl Kollwitz

Karl Kollwitz was born in the village of Rudau on 13th July, 1863. He became an orphan early in life and went to live with a family in Königsberg. As a young man he joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

In 1881 he met Käthe Schmidt. Her father was also an active member of the SDP. Like her father he was passionately interested in politics and introduced her to the writings of August Bebel.

This included his pioneering work, Woman and Socialism (1879). In the book Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another."

Karl Kollwitz became a medical student and in 1884 he asked Käthe to marry him. Her agreement to his proposal upset her father, Karl Schmidt, who feared that marriage would inhibit her artistic career. He arranged for her to study at the Berlin School for Women Artists, where she studied under Karl Stauffer-Bern.

In 1891 Karl qualified as a doctor and obtained a position in a working-class area of Berlin. In a response to the growing support of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), Otto von Bismarck had introduced the first European system of health insurance in which accident, sickness, and old age expenses of the workers and their families were covered by a government health insurance. As a socialist, Karl wanted to serve the poor and this new legislation made this possible.

Karl now asked Käthe to marry him. Käthe recorded in her journal how disappointed her father had been by the news: "He had expected a much faster completion of my studies, and then exhibitions and success. Moreover, as I have mentioned, he was very skeptical about my intention to follow two careers, that of artist and wife." Shortly before her wedding on 13th June, 1891, her father told her, "You have made your choice now. You will scarcely be able to do both things. So be wholly what you have chosen to be."

The couple moved to an apartment on 25 Weissenburger Strasse, on the corner of Wörther Platz. At first, Karl attracted very few patients. Käthe recorded: "We often stood at the window or on the tiny corner balcony, watching the passersby in the street below, hoping that one or other of them would find his way into the waiting-room." Next to Karl's office on the second floor was Käthe studio. It was a completely plain room as she liked to work without any visual distractions.

In May, 1892, Käthe Kollwitz gave birth to her first child, a son, they called Hans. She soon began to use her son as a model. In his first few months she did eighteen drawings of him. Karl kept his promise and "did everything possible so that I would have time to work". As soon as they could afford it, a live-in housekeeper was hired to help her with her child-rearing duties.

In 1896 Käthe Kollwitz gave birth to her second son, Peter. She later explained that this "wretchedly limited" her "working time". However, her work did not suffer: "I was more productive because I was more sensual, I lived as a human being must live, passionately interested in everything."

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28th June, 1914, triggered off the First World War. Käthe's two sons, Hans and Peter, immediately joined the German Army. She wrote in her journal on 30th September, 1914: "Nothing is real but the frightfulness of this state, which we almost grow used to. In such times it seems so stupid that the boys must go to war. The whole thing is so ghastly and insane. Occasionally there comes that foolish thought: how can they possibly take part in such madness? And at once the cold shower: they must, must!"

On 23rd October, 1914, Peter Kollwitz was killed at Dixmuide in Belgium on the Western Front. She wrote in her diary: "My Peter, I intend to try to be faithful.... What does that mean? To love my country in my own way as you loved it in your way. And to make this love work. To look at the young people and be faithful to them. Besides that I shall do my work, the same work, my child, which you were denied. I want to honor God in my work, too, which means I want to be honest, true, and sincere.... When I try to be like that, dear Peter, I ask you then to be around me, help me, show yourself to me. I know you are there, but I see you only vaguely, as if you were shrouded in mist. Stay with me.... my love is different from the one which cries and worries and yearns.... But I pray that I can feel you so close to me that I will be able to make your spirit."

Käthe Kollwitz found it difficult to use her art to deal with her grief. She wrote in her journal: "Stagnation in my work... When it comes back (the grief) I feel it stripping me physically of all the strength I need for work. Make a drawing: the mother letting her dead son slide into her arms. I might make a hundred such drawings and yet I do not get any closer to him. I am seeking him. As if I had to find him in the work... For work, one must be hard and thrust outside one-self what one has lived through. As soon as I begin to do that, I again feel myself a mother who will not give up her sorrow. Sometimes it all becomes so terribly difficult."

On 13th June, 1916, Käthe had been married to Karl for twenty-five years. In her journal she wrote: "I have never been without your love, and because of it we are now so firmly linked after twenty-five years. Karl, my dear, thank you. I have so rarely told you in words what you have been and are to me. Today I want to do so, this once. I thank you for all you have given me out of your love and kindness. The tree of our marriage has grown slowly, somewhat crookedly, often with difficulty. But it has not perished. The slender seedling has become a tree after all, and it is healthy at the core. It bore two lovely, supremely beautiful fruits."

The Spartakist Rising began in Berlin. Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party and Germany's new chancellor, called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Luxemburg who was arrested with Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck on 16th January. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were murdered while being taken to the prison.

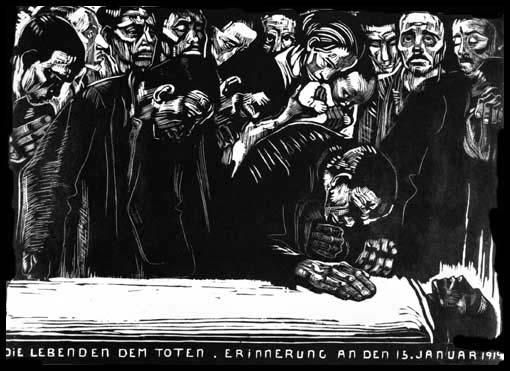

On the morning of the funeral Kollwitz visited the Liebknecht home to offer sympathy to the family. At their request, she made drawings of him in his coffin. She noted that there were red flowers around his forehead, where he had been shot. She wrote in her journal: "I am trying the Liebknecht drawing as a lithograph... Lithography now seems to be the only technique I can still manage. It's hardly a technique at all, its so simple. In it only the essentials count." However, she changed her mind and it became a woodcut.

The Karl Liebknecht woodcut was attacked by the German Communist Party (KPD) because it had not been produced by a member of the party. Kollwitz wrote in her journal: "As an artist who moreover is a woman cannot be expected to unravel these crazily complicated relationships. As an artist I have the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work upon me and then give them outward form. And so I also have the right to portray the working class's farewell to Liebknecht, and even dedicate it to the workers, without following Liebknecht politically."

On the death of Peter Kollwitz during the First World War, Käthe attempted to create a memorial to her son. Every attempt she made ended in failure. Eventually she decided to make two sculptures, The Mother and The Father. She was given permission to place them in the cemetery where he was buried.

In June, 1926, Karl and Käthe visited the cemetery in Dixmuide in Belgium, to decide where they were to be placed. She later recalled: "The cemetery is close to the highway.... The entrance is nothing but an opening in the hedge that surrounds the entire field. It was blocked by barbed wire which a friendly young man bent aside for us; then he left us alone. What an impression: cross upon cross.... on most of the graves there were low, yellow wooden crosses. A small metal plaque in the center gives the name and number. So we found our grave.... We cut three tiny roses from a flowering wild briar and placed them on the ground beside the cross. All that is left of him lies there in a row-grave. None of the mounds are separated; there are only the same little crosses placed quite close together.... and almost everywhere is the naked, yellow soil.... at least half the graves bear the inscription unknown German... We considered where my figures might be placed... What we both thought best was to have the figures just across from the entrance, along the hedge.... Then the kneeling figures would have the whole cemetery before them."

The memorial to her son was not finished until 1931. It went on display at the Prussian Academy of Arts until being moved to Belgium: "For years I worked on them in utter silence, showed them to no one, scarcely even to Karl and Hans; and now I am opening the doors wide so that as many people as possible may see them. A big step which troubles and excites me; but it has also made me very happy because of the unanimous acclaim of my fellow artists." Otto Nagel described the memorial as the "artistic sensation of the day".

Karl and Käthe Kollwitz helped organise a public manifesto calling for unity between the Social Democrat Party and the German Communist Party in order to combat to rise of fascism. Adolf Hitler responded by demanding that Kollwitz and Heinrich Mann, another organiser of the manifesto, should resign from the Prussian Academy of Arts. Kollwitz wrote to her friend, Emma Jeep: "Has the Academy affair reached your ears yet? That Heinrich Mann and I, because we signed the manifesto calling for unity of the parties of the left, must leave the Academy. It was all terribly unpleasant for the Academy directors. For fourteen years... I have worked together peacefully with these people. Now the Academy directors have had to ask me to resign. Otherwise the Nazis had threatened to break up the Academy. Naturally I complied. So did Heinrich Mann. Municipal Architect Wagner also resigned, in sympathy."

The Nazi government also banned Karl Kollwitz from working as a doctor in Berlin. Eric Cohn, a wealthy art collector in the United States, purchased some of her sculptures that enabled the couple to buy enough food to survive. Cohen also offered to help the couple to take refuge in the United States, but they refused as they did not want to be separated from their family.

Karl Kollwitz, who had an unsuccessful eye operation for cataracts, became increasing weak and by the outbreak of the Second World War he was completely bedridden. Käthe, who had to use a cane for walking, became his constant nurse and companion. He died in Berlin on 19th July, 1940.