Johann Eccarius

Johann Eccarius was born in Germany in 1818. He moved to London where he became friends with Karl Marx. A tailor, he was an active member of the London Trades Council. Marx wrote to Friedrich Engels to ask him if he could help fund Johann Eccarius: "If any money is forthcoming, I would suggest that Eccarius get some first so that he doesn't have to spend all day tailoring. Do try and see that he gets something, if at all possible." (1)

In June 1847, Eccarius helped Marx to establish the Communist League. Members of this international political party included Friedrich Engels, Wilhelm Liebknecht, Bruno Bauer, Oswald Dietz, Ernst Dronke, Andreas Gottschalk, Theodor Hagen, Ferdinand Freiligrath, Joseph Moll, Karl Schapper and Joseph Weydemeyer. (2)

The Austrian ambassador pointed out to Sir George Grey, the British Home Secretary, that members of the Communist League were discussing "regicide". Grey replied that "under our laws, mere discussion of regicide, so long as it does not concern the Queen of England and so long as there is no definite plan, does not constitute sufficient grounds for the arrest of the conspirators". In March 1851, the Prussian Minister of the Interior asked the British government to take "decisive measures against the chief revolutionaries" living in London such as Johann Eccarius. Again the government refused but did say they were willing to give these refugees financial assistance to emigrate to the United States. (3)

Johann Eccarius - Trade Unionist

In an article for a journal Marx believed that Eccarius was an important voice in the political debate and used him in his struggles with Wilhelm Weitling: "Eccarius is himself a worker in one of London's tailoring shops. We ask the German bourgeoisie how many authors it numbers capable of grasping the real movement in a similar manner? The reader will not how here, instead of the sentimental, moral and psychological criticism employed against existing conditions by Weitling and other workers who engage in authorship, a purely materialist understanding and a freer one, unspoilt by sentimental whims, confronts bourgeois society and its movement." (4)

Johann Eccarius developed consumption in 1859 and Marx described it as "the most tragic thing I have yet experienced here in London". (5) A few months later he noted that Eccarius "is again going to pieces in his sweatshop." During the scarlet-fever epidemic of 1862, three of his children died and Marx organised an appeal fund to cover funeral expenses. (6)

The historian Eric Hobsbawm has argued that in the early 1860s there was "a curious amalgam of political and industrial action, of various kinds of radicalism from the democratic to the anarchist, of class struggles, class alliances and government or capitalist concessions... but above all it was international, not merely because, like the revival of liberalism, it occurred simultaneously in various countries, but because it was inseparable from the international solidarity of the working classes." (7)

Johann Eccarius remained active as a trade unionist and joined a group of men that became known collectively as the "junta" who urged the establishment of an international organisation. George Odger, Robert Applegarth and William Allan were also members of this group. "The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle". (8)

On September 28, 1864, an international meeting for the reception of French trade unionists took place in St. Martin’s Hall in London. The meeting was organised by George Howell and attended by a wide array of radicals including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The historian Edward Spencer Beesly was in the chair and he advocated "a union of the workers of the world for the realisation of justice on earth". (9)

In his speech, Beesly "pilloried the violent proceedings of the governments and referred to their flagrant breaches of international law. As an internationalist he showed the same energy in denouncing the crimes of all the governments, Russian, French, and British, alike. He summoned the workers to the struggle against the prejudices of patriotism, and advocated a union of the toilers of all lands for the realisation of justice on earth." (10)

Johann Eccarius spoke on behalf of the Germans although he worked in London. (11) The meeting was a great success. "The big hall was filled to the point of suffocation. Speeches were made by Frenchmen, Englishmen, Italians and Irish." Politically... those who attended included "old Chartists and Owenites, Blanquists and followers of Proudhon, Polish democrats and adherents of Mazzini... Its social composition, however, was far more uniform. Workers formed the preponderating majority." (12)

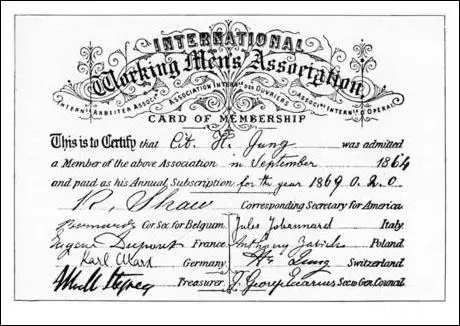

International Workingmen's Association

The new organisation was called the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA). Karl Marx attended the meeting and he was asked to become a member of the General Council that consisted of two Germans, two Italians, three Frenchmen and twenty-seven Englishmen (eleven of them from the building trade). Marx was proposed as President but as he later explained: "I declared that under no circumstances could I accept such a thing, and proposed Odger in my turn, who was then in fact re-elected, although some people voted for me despite my declaration." (13)

The General Council met for the first time on 5th October. George Odger was elected as President and William Cremer as Secretary. After "a very long and animated discussion" the Council could not agree on a programme. Johann Eccarius privately told Marx: "You absolutely must impress the stamp of your terse yet pregnant style upon the first-born child of the European workmen's organisation". (14) Marx told Friedrich Engels "the whole leadership is in our hands". (15)

Karl Marx agreed to outline the purpose of the organization. The General Rules of the International Workingmen's Association was published in October 1864. Marx's introduction pointed out what they hoped to achieve: "That the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves, that the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule... That the emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries." (16)

Friedrich Engels also joined the General Council but refused to to accept the office of treasurer: "Citizen Engels objected that none but working men ought to be appointed to have anything to do with the finances". Marx was asked to draw up the fundamental documents of the new organisation. He admitted that "It was very difficult to manage things in such a way that our views could secure expression in a form acceptable to the Labour movement in its present mood. A few weeks hence these British Labour leaders will he hobnobbing with Bright and Cobden at meetings to demand an extension of the franchise. It will take time before the reawakened movement will allow us to speak with the old boldness." (17)

In October 1869 Johann Eccarius helped to establish the Land and Labour League. Its formation was precipitated by discussion of the land question at the IWMA Basle Congress earlier that year. The League advocated the full nationalisation of land and was considered to be a republican working-class movement. Other members included Charles Bradlaugh, George Odger and Benjamin Lucraft. (18) It was a controversial organisation and after making one speech Odger was "set upon by a Conservative mob... and was severely beaten, suffering injuries that confined him for some time". (19)

Conflict with Karl Marx

Johann Eccarius was not the most popular member of the radical movements. According to Francis Wheen: "His gauche and humourless manner antagonised almost all who had to work with him." (20) David McLellan claims that he also upset his colleagues for his "staunch but tackless" support of Marx. (21)

Eccarius fell out with Karl Marx about the way he was running the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA). He thought his dogmatism would lead to the organisation breaking-up. In a letter written in May, 1872, he stated that "the day after tomorrow is my birthday and I should not like to start it conscious that I was deprived of one of my oldest friends and adherents." (22)

Eccarius attended the IWMA National Congress at the Hague, in September, 1872. According to newspaper reports, local people were warned "not to go into the streets with articles of value upon them" as the "International is coming and will steal them". Vast crowds followed the delegates from the railway station to the hotel, "the figure of Karl Marx attracting special attention". Marx dominating the proceedings "his black broadcloth suit contrasted with his white hair and beard and he would screw a monocle into his eye when he wanted to scrutinise his audience." (23)

At the congress a report was presented that showed Mikhail Bakunin had tried to establish a secret society within the IWMA and was also guilty of fraud. It also revealed details of the letter sent by Sergi Nechayev to Marx's publisher in Russia. The delegates voted twenty-seven votes to seven, that Bakunin should be expelled from the association. (24)

Marx had decided to retire from the IWMA and concentrate on the second volume of Das Kapital. Marx decided that the General Council of the IWMA should be moved to America. Engels proposed at the congress that the organisation should be transferred to New York City. The vote was very close with twenty-six for, twenty-three against and 9 abstentions. (25)

Friedrich Sorge now became general secretary of the International Workingmen's Association. The General Council in New York attempted to organise a congress in Geneva in 1873, but it was poor attended after Marx instructed his followers not to attend. Johann Eccarius rejected this advice and was the only delegate from England. Marx found this unacceptable and was now seen as an enemy. Shlomo Avineri, claims that Eccarius "came in for a generous measure of unearned contempt from his master and teacher." (26)

In 1874 Johann Eccarius joined forces with Robert Gammage to establish the Democratic and Trades Alliance Association. Most of its initial members were tailors or shoemakers based in London, many had been active Chartists and, later, supporters of James Bronterre O'Brien, and almost all were active in the First International. In 1875, the club renamed itself as the Manhood Suffrage League. (27)

Johann Eccarius died on 4 March 1889.

Primary Sources

(1) Yuri Mikhailovich Steklov, History Of The First International (1928)

The economic crisis of 1857 and the political crisis of 1859 culminated in the Franco-Austrian War (the War of Italian Independence), and there ensued a general awakening alike of the bourgeoisie and of the proletariat in the leading European lands. In Great Britain there was superadded the influence of the American Civil War (1861-4), for this led to a crisis in the cotton trade, which involved the British textile workers in terrible distress. This economic crisis, which began towards the close of the fifties speedily put an end to the idyllic dreams that had followed the defeat of Chartism. After the decline of the revolutionary ferment characteristic of the palmy days of the Chartist movement there had ensued an era in which moderate liberalism had prevailed among the British workers. Now, this liberalism sustained a severe, and, at the time it seemed, a decisive blow. There came a period of incessant strikes, many of them declared in defiance of the moderate leaders, who were enthroned in the trade union executives. In numerous cases these strikes were settled by collective bargains (“working rules”), then a new phenomenon, but destined in the future to secure a wide vogue.

Although many of the strikes were unsuccessful, they favoured the growth of working-class solidarity. Such was certainly the effect of the famous strike in the London building trade during the years 1859 and 1860, which occurred in connexion with the struggle for a nine-hour day, and culminated in a lock-out. At this time, a new set of working-class leaders began to come to the front-men permeated with the fighting spirit of the hour, and aiming at the unification of the detached forces of the workers. Such a process of unification was assisted by the steady growth of the “trades councils” which sprang to life in all the great centres of industry during the decade from 1858 to 1867. These councils, which were often formed as the outcome of strikes, or in defence of the general interests of trade unionism, integrated the local movements, and to a notable extent promoted the organisation of the proletariat...

At the head of the reviving working-class movement of Great Britain was a group of alive individuals who were advocates of a new departure in trade unionism, and became known collectively as the junta. This group consisted of William Allan, secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers; Robert Applegarth, secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters; George Odger, one of the leaders of a small union of skilled shoemakers (the Ladies’ Shoemakers’ Society), a noted London radical, and for ten years the secretary of the London Trades Council; and a number of influential personalities in the workers’ movement, among them Eccarius, a tailor by trade, a refugee from Germany, who had been one of the members of the old Communist League. The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle. Influenced by the Junta, the trade unions – at first in London and subsequently in the provinces – began to interest themselves in political reforms, such as the extension of the franchise, the reform of the obsolete trade-union legislation, the amendment of the law relating to “master and servant,” national education, etc.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)